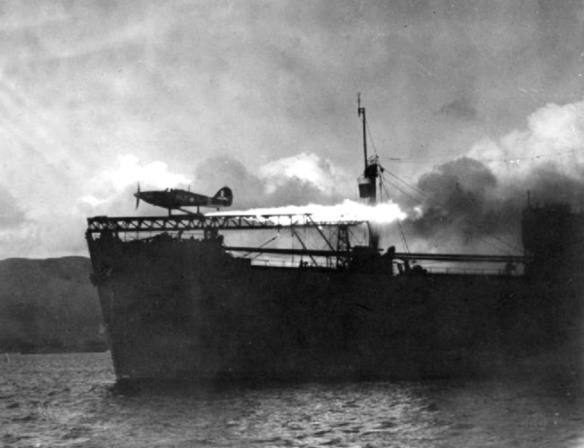

Test launch of a Hurricane at Greenock, Scotland, 31 May 1941

While the air marshals continued to pursue the idea of the expendable fighter with optimism – ‘Bert’ Harris, Deputy Chief of the Air Staff, and Wilfred Freeman, Vice-Chief, among them – the admirals on the whole were not enthusiastic. They still preferred to see the strengthening of Coastal Command. Churchill agreed with the air marshals. ‘The eight-gun fighter,’ he wrote, ‘will be a powerful deterrent.’ Yet it was the Admiralty who were the first to take action operationally. They ordered H.M.S. Pegasus, a former seaplane carrier that was being used as a catapult training ship, to sail on 9 December with the next outward bound convoy, carrying two Fulmars for catapulting. Tom Phillips thought little of their chances because of their speed limitations, but believed it was the best that could be done at short notice.

The priority the Admiralty were giving the problem, however, did not satisfy Churchill. ‘What have you done,’ he demanded of Pound on 27 December, ‘about catapulting expendable aircraft from ships?’ Three days later, on 30 December, a final decision was taken – although still only in principle – to fit out an unspecified number of merchant vessels for the catapulting of one or more unspecified types of aircraft. They were to be known as Catapult Aircraft Merchant Ships, or Camships, and their numbers were to depend on trials and an operational experience. These Camships were to sail as an integral part of convoys: they would fly the Red Ensign, and they would carry normal freight. Since they would be in the danger zone for no more than a few days at a time, once during the outward journey and once on the return, the watch-keeping was unlikely to be so onerous that one pilot could not cope with it. But where were the vessels to come from? To withdraw freight carriers from convoy service for the fitting of catapults and radar equipment, and for training, would impose an unacceptable reduction of working tonnage, so only vessels under construction, big enough to take a 75-foot steel runway mounted over the forecastle head, were to be fitted. This meant a delay of several months before the scheme could start operating.

Meanwhile, as a stopgap, four ships that were being fitted out for service as auxiliary naval vessels were to be adapted for catapult work. These ships, which had been banana boats in peacetime, were the Ariguani, the Maplin, the Patia and the Springbank, and they were to be known as Fighter Catapult Ships. Each was to carry two expendable fighters, one hoisted in readiness on a catapult trolley and the other stored as a reserve, with the necessary gantries to hoist it into position. As naval auxiliaries they would fly the White Ensign and form part of the convoy escort; they would not carry freight. They would be employed in the danger zone only, accompanying convoys to the western limit before returning with incoming convoys. With approximately seventeen days of concentrated watch-keeping in prospect, and a spare aircraft, they would need three pilots to cope.

While the British sought to improvise an antidote to the Condor, the Germans aimed to capitalise on a weapon that was itself an improvisation. Before the war the Focke-Wulf Condor, designed by the firm’s technical director Kurt Tank, had broken many records on the commercial air routes and had gone into service with Lufthansa and Danish Air Lines. An order from Japan early in 1939 had stimulated design work on a reconnaissance version, and this proved useful when, on the outbreak of war, Germany found herself lacking any long-range reconnaissance aircraft. Göring, urged by Udet, had cancelled production of a projected long-range bomber, and Hitler, believing that he could avoid war with Britain, had trusted to the blitzkrieg for a quick and easy victory. The only suitable aircraft on the drawing board was the Heinkel 177, but it was nowhere near production. The Luftwaffe thus found itself obliged to look for a suitable aircraft to fill the gap. It was Edgar Petersen, formerly Director of the Instrument Flying School at Celle and a flyer with much long-range peacetime experience, who suggested the Condor.

Some progress had already been made with the training of crews. With the increasing risk of war against Britain if Poland were invaded, an investigation was ordered in the spring of 1939 which revealed that all combat units lacked experience of flying over water, and a special course was established at Oldenburg to which Petersen was appointed Director. Then on 1 August 1939, with the formation of the new Fliegerkorps X, Petersen was transferred to its staff.

Summoned soon afterwards to General Hans Jeschonnek, the Luftwaffe Chief of Staff, Petersen was ordered to prepare proposals for the formation of a long-range unit for attacking marine targets in the Atlantic. An examination of available types showed Petersen that the FW 200 alone had sufficient potential range, and he submitted his proposals accordingly. Jeschonnek approved, the Focke-Wulf company were duly asked to produce a military version and ten machines were ordered. Four of these were earmarked for transport work, but the remaining six were fitted with defensive armament and bomb-racks. Auxiliary fuel tanks built into the fuselage increased their maximum range to over 2,000 miles. To prepare for the delivery of these six modified Condors (or Kuriers, as the military version was called, though the name Condor soon reasserted itself), a Staffel was formed under Petersen at Bremen on 1 October.

Petersen was careful to choose pilots who were expert in blind flying, and navigators who had specialised knowledge of astro navigation. Most of them had served as instructors at the instrument flying schools, and the Staffel soon developed the discipline and charisma of an élite corps.

While the Condors underwent conversion, the crews passed the winter in training flights over the North and Baltic Seas. Then in the spring of 1940 the unit was redesignated I./KG 40 and began operations, flying armed reconnaissances in support of the German invasion of Norway and bombing sorties against British shipping engaged in the campaign.

Following the Allied débâcle the unit was expanded into two Staffeln, redesignated I. Gruppe KG 40, and re-equipped with an improved mark of Condor, the 200 C-1, which differed from its predecessor principally in that the ventral or belly gondola was considerably lengthened, allowing a 20-millimetre cannon to be fitted to the forward section to silence the guns of target vessels, firing forward and down. The ventral armament was completed by a 7.9 millimetre machine-gun in the rear of the gondola, firing aft and down. The dorsal armament consisted of a 7.9 machine-gun in a forward turret, with an all-round field of fire, and a similar weapon to the rear. The four BMW engines, as in the earlier version, each developed 850 hp, and they could lift five or six 250 kg (551 lb) bombs and a crew of five. These consisted of pilot, co-pilot, navigator (who also served as radio-operator, bomb-aimer and gunner), engineer-gunner, and rear dorsal gunner. The economical cruising speed was approximately 180 mph and the radius of action with a full bomb-load about 1,100 miles.

Early in July, following the fall of France, the transfer of the new Gruppe to a newly acquired airfield at Bordeaux-Merignac was begun; but its true métier was still not fully understood, except perhaps by Petersen. The first phase of the Battle of Britain had started and it was perhaps inevitable that KG 40 should be thrown into the fray. With two big aerial mines suspended externally, the Condor crews, operating in darkness, began a minelaying campaign against Britain’s east coast ports; but thus handicapped the Condors suffered disastrously in speed and stability and became too vulnerable a target for the ground defences. When two Condors were lost on minelaying operations on the night of 19/20 July, Petersen urged that such operations be discontinued. Unable to get permission through the ‘usual channels’, he by-passed them and appealed by telephone direct to Jeschonnek. ‘This wasteful business of mining will have to stop,’ he told Jeschonnek. ‘Otherwise we shall lose all our planes and crews.’ Although taken aback at Petersen’s outburst, Jeschonnek knew his man and agreed. (The two men had served together in the secret air force in Russia in 1929.) Petersen went on to urge that the Gruppe be allowed to begin the work for which it was formed, equipped and trained, and Jeschonnek was sympathetic. But with the Battle of Britain rapidly approaching its climax, the Gruppe was next recruited into the night bombing of Britain’s cities, and missions were flown to the Liverpool-Birkenhead area on four successive nights in August. By this time, however, the Condors had begun operating against Allied merchant shipping, mostly in the North Atlantic, and they soon began to enjoy spectacular success. Co-operating with Marine Gruppe West at Lorient, the Condors took off singly from Bordeaux in the early morning and flew out across the Bay of Biscay as far as 24 degrees west before describing a right-hand semi-circle that took them north of Scotland on their way to a landing in Norway, returning by the same route two days later. Any convoys cut by this huge arc thus came under surveillance, and single ships and stragglers were attacked on sight.

Lacking any sophisticated form of bomb-sight, the Condor crews attacked their targets visually from abeam at low level, diving down to masthead height, where the guns of escort vessels were powerless to interfere. ‘You could hardly miss,’ says Petersen. ‘Even without a bomb-sight at least one of the bombs would find the ship provided you kept low enough.’ Some pilots, learning from experience that what little armament the merchant ships themselves carried was invariably mounted astern, directed their bombing runs along the length of vessels from the bow, pulling up steeply after they had dropped their bombs to avoid collision with masts. It was in this period, from late August to mid-November 1940, that the Condors sank nearly 90,000 tons of Allied shipping and damaged a good deal more.

These were the sinkings that first stimulated the search for a counter-measure by the British naval and air staffs. But they did not satisfy Petersen. Despite well-earned awards of the Knight’s Cross to pilots like Captains Fliegel and Daser and Lieutenants Verlohr and Buchholz, as well as to Jope and himself, and despite the posting-in of the cream of the bomber training schools, Petersen could not contain his frustration. At just about the time that Stevenson was warning Portal that an intensification of the Condor threat must be anticipated, Petersen was appealing to Hitler for a dramatic increase in Condor production. ‘If I had enough aircraft to send out between forty and fifty a day,’ he is reported to have said, ‘the blockade of England could be really effective.’

Clearly Petersen was not given to over-statement, a characteristic which may have told against him in Nazi Germany. Anyway, for the moment at least, he was no more successful in his pleadings than Stevenson had been. Throughout 1940 only thirty-six Condors were built, and although an improved variant – the 200 C-3, incorporating four 1,000 h.p. Bramo-Fafnir radial engines and other refinements – was in preparation, production was still limited to four or five machines a month. Indeed throughout the winter of 1940/41 the Gruppe continued to operate two Staffeln on about fifteen aircraft, of which rarely more than eight were serviceable at any one time.

This problem of serviceability, which was to dog the Condor for many months, was directly traceable to the haste with which the military version had been adapted from the commercial. The basic structure of the Condor, as has been noted, was not designed to meet the demands of continuous operational flying, and the chosen methods of attack, often involving violent evasive manoeuvres at low level, imposed too great a strain. The most frequent faults were that the rear spar failed and the fuselage aft of the trailing edge of the wing cracked.

Despite these drawbacks, however, the two Condor Staffeln, backed up by one small factory with an output of little more than one aircraft a week, continued to sink ships and exert an influence on the sea war out of all proportion to their size. The short-term measures taken against them proved inadequate, further bombing raids on their bases found defences strengthened and dispersal effective, and the expendable fighter, coupled with strong defensive armament on all merchant ships, seemed the only hope of relief.

This relief, though, was still a long way off, and meanwhile the Naval Air Division of the Admiralty put forward an imaginative proposal to erect dummy aircraft on selected ships on a simulated catapult The Intelligence Division would then spread a rumour that merchant ships were being equipped with fighters, and it might be some time before the bluff was called, giving a deterrent effect meanwhile. Objections were that the deception would be so obvious at the ports of embarkation that the enemy would soon get to know the truth, and that even it the ruse didn’t fail completely it might only attract Condor attack. But with real fighters and real catapults in prospect, the enemy might well guess wrong at a later date. Five old Fokker seaplanes and two dummy biplanes were sent to Liverpool and Glasgow, but only two had been fitted when, in June 1941, the idea lapsed on the introduction of the first Camships. It was, however, resuscitated later on the Russian convoys.

The need for fighters at least equal in performance to the Hurricane was underlined on 11 January when a Fulmar was catapulted from Pegasus to attempt an interception. This launching, the first of the so-called expendable fighters, took place 250 miles off the Irish Coast and the pilot was able to reach land, so it lacked an essential element; but there were important lessons to be learnt from it. The ship being attacked was five miles distant from Pegasus on the port beam, clearly visible, and although the Fulmar got off quickly the ship was bombed and hit and the Condor pilot already heading for the sanctuary of cloud when the Fulmar began the chase. Indeed the cloud conditions were such that a launching would hardly have been ordered had the pilot not been within reach of land. In the short pursuit that developed, the Fulmar was exposed as far too slow. The Fulmar pilot, Petty Officer F. J. Shaw, landed safely at Aldergrove in Northern Ireland.

By this time the Condors were finding it more profitable to head out into the Atlantic to a point about 25 degrees west, carry out a two-hour search, and return to Bordeaux, rather than continue to Norway; and their tactics paid off so well that forty-three ships suffered attack by Condor in the first two months of 1941, of which twenty-six were sunk. The worst day of all was 9 February, when five Condors led by Captain Fritz Fliegel sank five freighters in the same convoy, 400 miles south-west of Lisbon and over a thousand miles from Bordeaux.

The Condor crews were claiming 363,000 tons of Allied shipping sunk to date, eighty-five ships in all. Nineteen of these were sunk in February alone. The British knew only too well that, unlike some of the bragging of the Nazi leaders, the claims of the Condor crews were soundly based.

In these early months of 1941, sorties by German surface raiders, among them the battle-cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the cruiser Hipper, wrought further destruction, while the U-boats, which as in 1914 had begun the war underprepared, were known to be building up for a decisive campaign. On 30 January Hitler boasted that a combination of sea and air power would soon encompass Britain’s starvation and surrender. ‘In the spring,’ he promised, ‘our U-boat war will begin at sea, and they will notice that we have not been sleeping. And the Air Force will play its part.’

Early in March 1941 the Luftwaffe established a new anti-shipping command under Fliegerführer Atlantik, with a headquarters near the U-boat base at Lorient. Its task was to direct air operations against Allied shipping in the Atlantic in close co-operation with the C-in-C Submarine Fleet. Up to this time it had been rare for Condors to shadow convoys in order to call up U-boats, but now the arrival of a Condor often presaged attack by U-boat.

Churchill’s reaction was typical. ‘We have got to lift this business to the highest plane, over and above everything else,’ he told Pound. Nine months earlier, on 18 June 1940, he had heralded the Battle of Britain. Now he proclaimed the Battle of the Atlantic.

In view of various German statements [he announced in a historic directive of 6 March 1941], we must assume that the Battle of the Atlantic has begun …

We must take the offensive against the U-boat and the Focke-Wulf wherever and whenever we can. The U-boat at sea must be hunted, the U-boat in the building yard or in dock must be bombed. The Focke-Wulf and other bombers employed against our shipping must be attacked in the air and in their nests.

Extreme priority will be given to fitting out ships to catapult or otherwise launch fighter aircraft against bombers attacking our shipping. Proposals should be made within a week …

Preparations for the employment of the expendable fighter after nearly four months of uncertainty and delay, were at last given the impetus that was needed. Within three months of this directive, four Fighter Catapult Ships were operating and the first of the new Camships was about to sail.