Bolivia was not Chile’s only potential enemy. During the 1870s, the Argentine government, having tamed its unruly provincial caudillos, launched campaigns to “pacify” its Indian population. This thrust into the interior brought Argentines into an unwelcome contact with Chile, for Chileans had been filtering into the largely unpopulated wilds of Patagonia – and had, of course, been on the Straits of Magellan since 1843. Argentina demanded that Chile recognize its sovereignty over both areas. Chilean opinion, for the most part, appeared willing to cede Patagonia, but to lose control of the Strait would expose the country to the risk of an Argentine naval attack as well as deny it access to the Atlantic. The government was strongly urged by the press to reject the Argentine claims.

President Anibal Pinto selected the historian Diego Barros Arana to negotiate a settlement. The choice proved unfortunate. Barros Arana violated his instructions, agreeing to cede Patagonia and to grant Argentina partial control of the Straits. Barros Arana’s largesse provoked rioting in Santiago. War suddenly seemed imminent, but Pinto accepted a formula proposed by the Argentine consul-general (given plenipotentiary powers by Buenos Aires), and in December 1878 the two countries signed the “Fierro Sarratea” treaty: this postponed the question of sovereignty for future discussion, but permitted joint Argentine-Chilean control of the Straits. Although Pinto managed in this way to avert a war, his handling of the Argentine crisis damaged his already shaky reputation. The opposition seized on the boundary issue, depicting the president as a craven weakling who had surrendered to Buenos Aires.

Pinto’s problems were soon compounded by a revival of friction with Bolivia. In December 1878, the Bolivian dictator Hilarion Daza, a barely literate sergeant who had shot his way into the presidency, increased the taxes on the Compania de Salitres y Ferrocarril de Antofagasta. This clearly violated the 1874 agreement, but Daza fully expected that Chile would again “strike its flag as it did with Argentina.” Should the Moneda resist, he could invoke a secret treaty signed in February 1873, in which Peru had promised to help Bolivia in the event of a war with Chile. The combination of Peru’s not insubstantial fleet, in conjunction with the allied armies, Daza concluded, would bring easy victory.

Pinto had little room to negotiate. The Campania de Salitres’s share holders had suborned a number of newspapers, which shrilly demanded that the government enforce its treaty obligations. Opposition politicians, who used the border dispute with Bolivia as an issue during the 1879 congressional election campaign, warned Pinto and his Liberal followers not to surrender to the Bolivian dictator. Both the unscrupulous politicians and the jingoistic press organized demonstrations in Santiago and Valparaiso to invigorate the national mood. These tactics had their effect. Inflamed by “patriotic gore,” the public, which had already demonstrated a distinct willingness to fight during the Argentine crisis, amplified the demands of the “hawks.” Watching a patriotic mob marching in front of his house, Antonio Varas, then briefly minister of the Interior, told the president that unless he moved against Bolivia “[the people] will kill you and me.”

In February 1879, motivated by either anger or fear, Pinto ordered the Army to seize Antofagasta as well as the territory ceded to Bolivia under the 1874 treaty. Pinto would have been content to stop at Antofagasta, but he could not. The press and the opposition alike demanded that he order the Army north of the old border in order to protect Chilean positions. Pinto refused, perhaps believing that Daza would accept a return to the status quo ante. But Daza did not: two weeks after the Chilean occupation of Antofagasta, Bolivia declared war.

Pinto, like most other Chilean politicians, had known for years about the “secret” Peruvian-Bolivian alliance. He hoped, however, that Lima might be persuaded to remain aloof from the conflict. For a while such an outcome even seemed likely: Peru’s president, Manuel Prado, offered to mediate. At the same time, however, the Peruvians showed obvious signs of readying their navy and army – actions not lost on the Chilean press, which demanded that Pinto move against Lima before it was too late. The president labored mightily to avoid a conflict, even offering Peru economic concessions in return for neutrality. He was overwhelmed by the strength of public opinion, and finally demanded that Peru state openly whether it planned to honor the 1873 treaty. When the answer came, in the affirmative, in April 1879, Chile declared war on both Bolivia and Peru.

Pinto had good reason to hesitate before involving Chile in a war with its northern neighbors. Years of budget-cutting had deprived the Army of one-fifth of its men; the Navy had decommissioned warships; the territorial reserve, the Guardia National, had shrunk in size by more than two-thirds. Chileans now faced two enemies whose combined armed forces outnumbered them two to one. Equipped with outmoded weapons (which posed more of a danger to the user than the prospective target), lacking medical and supply corps, the Army was now called upon to fight a war far from the country’s heartland, and without decent lines of communication. For Chile to triumph, control of the sea was essential: only this would enable the Army to attack the enemy on its home ground. Without it Chile was exposed to invasion, blockade, or (as Spain had shown in 1866) bombardment. Peru’s navy (Bolivia did not have one) possessed two ironclads, as well as support vessels; the Chilean fleet also included two ironclads but these, like most of the Navy’s other ships, were in poor condition. The immediate outlook did not look promising. Hoping to win the maritime supremacy so urgently needed, Pinto requested the Navy’s commander, Admiral Juan Williams Rebolledo, to attack the enemy fleet at Callao, its fortified home base. Williams refused. Instead he blockaded Iquique, the port through which Peru exported nitrates (its principal source of revenue), in the belief that the Peruvian president would have to either order his fleet south or face financial ruin. Thus the Chilean squadron idled off Iquique harbor, waiting for the Peruvian attack. Public opinion, soon tiring of Williams’s passive waitinggame, demanded that he strike at the enemy. Anxious to enhance his popularity (Williams planned to capitalize on his command to make a bid for the presidency in 1881), the admiral finally decided to attack the Peruvian ironclads, the Huascar and the Independencia, as they lay at anchor in Callao. Without informing the Moneda, he sailed north, leaving two wooden ships, the Esmeralda and the Covadonga, to maintain the blockade of Iquique.

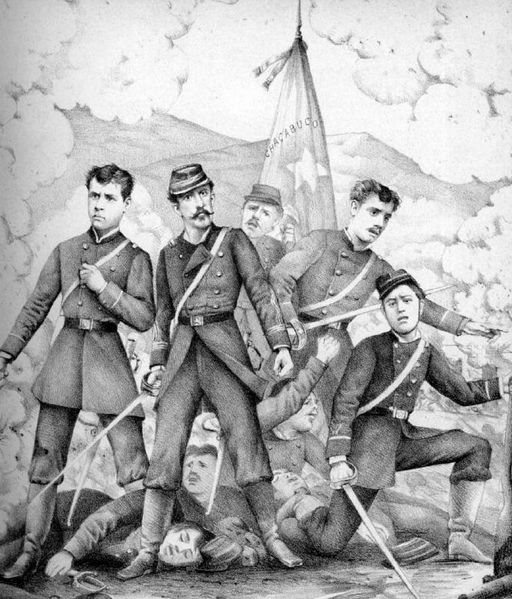

Williams’s expedition was a fiasco: the Peruvian ships had already left when the Chilean squadron arrived. (Evidence indicates that Williams chose to attack Callao knowing full well that the ironclads had already sailed.) When the admiral at last slunk back to Iquique, he learned that the Peruvian fleet had taken advantage of his absence to break the blockade. Not only had the Peruvian admiral, Miguel Grau, successfully reinforced Iquique, but he had also sunk the Esmeralda in the first memorable sea-battle of the war (May 21, 1879). The battle of Iquique provided Chile with the supreme hero of the war, Captain Arturo Prat, whose death in a hopeless attempt to board the Huascar gave the country an impeccable symbol of patriotic sacrifice and duty. The only bright spot in this disaster was that during a high-seas chase of the Covadonga, the Independencia’s captain ran his ship aground – thus almost halving Peru’s effective naval strength.

Rather than take advantage of this unearned advantage, Williams sulked in his cabin, nursing a bruised ego and an imaginary illness. By now the government desperately wished to dismiss him, but the admiral’s allies in the Conservative party successfully insulated their potential future candidate from retaliation. During the winter of 1879, meanwhile, Chile continued to suffer naval reverses: in July the Peruvians captured a fully loaded troop transport, the Rimac, an event that provoked massive riots in Santiago; Admiral Grau successfully terrorized the northern ports while another Peruvian warship, the Union, threatened Chilean supply lines through the Magellan Straits. Finally, in August 1879, and again without informing the government, Williams broke off the blockade of Iquique. This time not even Williams’s most ardent defenders could protect him. He was replaced by Admiral Galvarino Riveros, who immediately set about refitting his ships. In October the Chilean fleet trapped Grau off Punta Angamos. After a brutal exchange of fire (in which Grau perished), the Chileans captured the Huascar. It was later taken to the naval base at Talcahuano, where it is still on display.

Chile was now master of the sea-lanes. The way to the north was open. But if the Navy was ready, the Army was not. Its 74-year-old commander, General Justo Arteaga, possessed neither the physical nor the mental resources to mount an expedition to Peru. Like Williams, Arteaga also enjoyed the protection of political allies and therefore seemed beyond retribution. In a rare moment of lucidity, fortunately, he resigned before he could do too much damage. His successor, Erasmo Escala, proved only marginally more effective. A fervent Catholic (he often ordered his troops to attend religious ceremonies) with close ties to the Conservative Party, the new commander seemed temperamentally incapable of working with anyone who challenged his authority or questioned his judgment. But for political reasons Pinto could ill afford to replace him. Instead he ordered Rafael Sotomayor and Jose Francisco Vergara, both civilian politicians (the first a National, the second a Radical), to assist (and by implication to supervise) Escala, especially by providing logistical support.

In November 1879 Escala’s troops landed at Pisagua, in the Peruvian province of Tarapaca. The assault, while successful, was not without its flaws: an error of navigation put the fleet off course, and the officer in charge of the invasion botched the landing. But the Chileans emerged as paragons of military virtue in comparison with their opponents. The Allies had planned a counterattack which called for Daza to strike from the north while the Peruvian General Juan Buendfa would attack from the south, thus crushing the Chilean expedition between the allied armies. The plan misfired badly. Daza, whose incompetence (already amply displayed) decimated his units as they marched from La Paz to the coast, simply deserted. Rather than advance through the desert to the south (admittedly difficult), the Bolivian dictator ordered his men to fall back on their base in Arica. Buendia, unaware of Daza’s defection, continued to drive northward expecting to rendezvous with the Bolivians. The Chileans, of course, knew nothing of these events. Escala remained close to the coast, keeping a watchful eye on the north, assuming that an attack would come from that quarter. Anxious to secure a dependable supply of water for the expedition, Rafael Sotomayor ordered his colleague Vergara (now serving as an active officer) to capture the oasis of Dolores. Vergara had accomplished this mission when one of his patrols, reconnoitering the area, ran into the advance guard of Buendia’s army.

Although unpleasantly surprised, the Chilean commander, Colonel Emilio Sotomayor, managed to position his men on a convenient hill, the Cerro San Francisco, before the enemy struck. A skillful use of artillery as well as sheer fortitude gave the Chileans the battle (November 19, 1879). The Bolivian soldiers, despondent and thirsty, made off for the altiplano. The Peruvians retired in more orderly fashion to the village of Tarapaca. Rather than pursue his exhausted opponents, Escala ordered his men to attend a Mass of thanksgiving. Having fulfilled their religious obligations, the Chileans finally attacked, and a force under Vergara advanced on Tarapaca. This time, it was the Peruvians who routed the Chileans, inflicting serious casualties (including more than 500 dead) in a singularly bloody battle (November 27). Notwithstanding this victory, Peru now abandoned Tarapaca province, enabling the Chileans to occupy Iquique and its nitrate-rich hinterland.

Success in the Tarapaca campaign did not prevent squabbles in the victors’ camp. Escala, for his part, had fallen under the spell of a coterie of Conservative aides, who assured him that he could parlay his military triumphs into a presidential candidacy. He frequently quarreled with Sotomayor (who was increasingly exercising military command) and with anyone who doubted his military genius. In March 1880, apparently to impress his importance on the government, Escala threatened to resign. To the general’s great surprise, Pinto called his bluff and accepted the resignation.

Under a new commander, General Manuel Baquedano, Chile launched its third northern campaign in February 188o, landing an expedition at Ilo with the aim of capturing Tacna province. With no Peruvian counterattack in sight, and remembering Escala’s ineptitude, Pinto reluctantly ordered Baquedano to move inland. Baquedano had to surmount desperate supply problems, but swiftly captured Moquegua and defeated the Peruvians at the battle of Los Angeles (March 22). Despite its success, the opening of the campaign lacked a little luster: during one surprise attack, a unit got lost and had to ask the local people for directions.

Anxious to capture Arica, Tacna’s port and a vital strategic point, Baquedano marched his men overland, a journey which took a heavy toll of lives. After about one month the Chileans reached Campo de la Alianza, a fortified Peruvian position on the outskirts of Tacna. Although Vergara (Sotomayor had recently died suddenly) urged Baquedano to outflank the strongpoint, the general insisted upon a frontal assault. Baquedano’s soldiers triumphed (May 26), but at a very high cost: three out of every ten Chilean soldiers were either killed (nearly 500) or wounded (around 1,600). Despite these heavy casualties, the army moved on to Arica, and captured its strongly fortified Morro, the Gibraltar-like rock that loomed (as it still looms) over the port, in one of the most rapid and heroic assaults of the war (July 6). From start to finish it took fifty-five minutes, around 120 Chileans dying in the attack.

Victory in the Tacna campaign did not cause unalleviated delight in Chile. The public, learning of the cost in blood of Baquedano’s sledgehammer tactics, was outraged. Indeed, one journalist was so appalled that he suggested Santiago hold “a dance of death” rather than a victory ball to celebrate the triumph at Tacna. 6 Public anger was further exacerbated by news that the Peruvians had sunk two more ships, the Loa and Covadonga (July-September 188o). Demands for an assault on Lima now grew irresistible. Fulfilling these demands proved difficult. Most of the Army’s supplies were exhausted: civilians like Vergara had to labor hard to find men and equipment, and the means to transport an expedition to the new battle zone. Thanks to prodigious efforts, Baquedano’s troops were poised by January 1881 to attack the Peruvian capital. As during the Tacna campaign, Vergara suggested that Baquedano try to outflank the Peruvian defenses to minimize the casualties, while allowing Baquedano to capture the city. The general, apparently a disciple of the elan vital school of military tactics, rejected this advice. As one admirer subsequently noted, only a frontal assault would allow the Chileans to demonstrate their virility.

On January 13, 1881, Baquedano’s troops duly demonstrated their virility by breaking through the Peruvian positions at Chorrillos. As some of the victors mopped up pockets of resistance, others amused themselves by pillaging the locality and terrorizing its inhabitants. Two days later the Chileans attacked and overwhelmed the Peruvian defenses at Miraflores in a second bloody battle. (Chilean casualties for these two battles included at least 1,300 dead and more than 4,000 wounded; Peruvian losses were higher.) By the evening the Peruvian government had fled and the first Chilean units (one composed of Santiago policemen) entered Lima itself. For the third time in sixty years, the former viceregal capital lay at the feet of a Chilean army.

The fall of Lima did not end the war. Chile demanded the cession of Tarapaca, Arica, and Tacna as war reparations and as a buffer for Chile in case Peru decided to stage a revanche. Nicolas Pierola, who had replaced President Prado in 1879 and who now moved his government to the mountains, refused to cede an inch. Like Mexico’s Juarez, he promised to wage a war of attrition to expel the occupying army. Chileans might dismiss Pierola as a bombastic fool, but they were nevertheless in an uncomfortable position. They could hardly withdraw from Peru without a peace treaty. But neither could they secure a peace treaty without convincing or coercing a Peruvian government to accept their demands. Francisco Garcia Calderon, the hapless lawyer who became the president of Chilean-controlled Peru in February 1881, was as adamant as Pierola (still at the head of his government) in his refusal to contemplate territorial concessions.

While the Chilean government tried to force a settlement, Peruvian resistance stiffened. Bands of irregulars, montoneros, now appeared; under the leadership of seasoned officers like Andres Caceres they harassed and attacked the occupying army. A punitive expedition was dispatched into the Peruvian interior in hopes of crushing these guerrillas. Increasingly many Chileans began to fear that their great military victory was destined to prove pyrrhic.

A complicating factor at this point was the role of the United States, which had earlier (October 1880) attempted to mediate between the belligerents.’ The U.S. Secretary of State, James G. Blaine, wished to use the War of the Pacific to blunt what he saw as British imperialism while extending what some might term the American variety. Blaine decided he could best accomplish these goals by encouraging Garcia Calder’s refusal to cede territory. The Chilean government eventually tired of this game and jailed Garcia Calderon, an action that infuriated Blaine. For a short while it even seemed possible that the United States and Chile might go to war. The crisis was ended by the assassination of President James A. Garfield (September 1881). The new president, Chester A. Arthur, replaced Blaine with Frederick Frelinghuysen, who quickly abandoned his predecessor’s truculent foreign policy. Henceforth the United States was not to oppose Chilean demands for territory.

But if the diplomatic situation improved, Chile’s military situation did not. Early in 1882, the government sent another expedition into the Peruvian highlands. Adrift in a hostile environment, cut off from their supplies, and constantly under attack from guerrilla bands, the Chilean army completely failed to pacify the interior. After months of fruitless wanderings in the mountains, the troops were ordered to withdraw to the coast. As they retreated, Caceres struck his most devastating blow. At the battle of La Concepcion (July 9, 1882) the Peruvians annihilated an entire Chilean detachment of seventy-seven, not only killing the soldiers but also mutilating their remains.

The disaster at La Concepcion brought home to the Chilean public the fact that its soldiers were still engaged in a bloody war. As the casualties mounted, as the men succumbed to the sniper’s bullet or to disease, the press questioned why Chilean youth had to die “in places … which could have been left alone without compromising the cause of Chile.”‘ Why, others demanded, was the nation wasting its blood and its treasure on a war which threatened to become the “cancer of our prosperity”? As one provincial newspaper concluded: “The thing is to make peace, be it well done or not.”

A number of prominent Peruvians, too, had tired of the war. One of these, Miguel Iglesias, who established his own new government (with Chilean support) at Cajamarca, A number of prominent Peruvians, too, had tired of the war. One of these, Miguel Iglesias, who established his own new government (with Chilean support) at Cajamarca, appeared willing to negotiate. While willing to give up Tarapaca, he balked at ceding Tacna. The government in Santiago, anxious to extricate the nation from the diplomatic morass, was now willing to make concessions. It stuck to its demand for Tarapaca, but proposed to occupy Tacna and Arica for ten years, following which a plebiscite would determine the final ownership of the territory. Although Iglesias accepted these terms, Caceres would not – and he was still at large. Another Chilean expedition marched into the interior, determined to hunt him down. After months of hazardous maneuvering, the Chileans finally defeated him at the battle of Huamachucho (July 20, 1883). With Caceres thus subdued, Iglesias duly signed a peace treaty, at Ancon on October 20. Nine days later, Chilean troops occupied the last pocket of montonero resistance, the beautiful city of Arequipa.

Bolivia still formally remained a belligerent, though had taken no part in the war since the Tarapaca campaign. The Treaty of Ancon, however, persuaded even the most truculent Bolivians to seek peace. Although vanquished, the country managed to obtain generous terms: the “indefinite truce” signed in April 1884 granted Chile only the right to temporary occupation of the Bolivian littoral. The armistice with Bolivia marked the end of the War of the Pacific, almost exactly five years after it had begun.

The Chilean capture of Lima in January 1881, we should note here, provided an incidental diplomatic dividend. With Peru out of the war, Argentina could ill afford to press its claims to the Straits of Magellan. In July 1881 Chile and Argentina signed a treaty which confirmed both Argentine sovereignty over Patagonia and Chilean control of the Straits. In addition, both nations agreed to demilitarize the waterway, while Argentina undertook never to block the Atlantic entry into the Straits.

Apologists for the defeated Allies have traditionally described Chile as the Prussia of the Pacific – a predatory land looking for any excuse to go to war with its hapless neighbors. Common sense alone indicates otherwise. Chile’s armed forces in 1879 were both small in size and poorly equipped. Moreover, too many officers owed their high ranks to political connections rather than to technical proficiency. The incompetence of men like Williams and Escala forced the government to become involved in the conduct of the war and to provide the logistical support. Some professional soldiers resented this intrusion, calling upon their political allies to protect them from the government’s attempts to direct the war. This political intervention, by insulating inefficient officers, almost certainly prolonged the war.

Relations between the military and civilian society often proved acrimonious. The officers resented institutions such as freedom of the press, particularly when it was used to describe the conduct of the military in unflattering language. In San Felipe, for example, piqued subalterns destroyed a newspaper office in retaliation for a critical editorial. Baquedano had journalists jailed for pillorying his skills. A more egregious incident occurred in 1882, when Admiral Patricio Lynch, then military governor of Lima, claimed (in effect) that he was above the law when he arbitrarily abridged a Chilean colonel’s civil rights. Unimpressed by Lynch’s arguments, the Chilean supreme court overruled him.

The War of the Pacific forced the Army into the lives of civilians to an extent not seen before. When the first rush of patriotic enlistments tapered off, the armed forces resorted to impressment. Although this was clearly illegal, public officials tolerated (and in some cases even encouraged) such activities as long as the recruiters confined themselves to dragooning the town drunk, the petty criminal, or the vagrant. Eventually, however, the military began to seize respectable peasants, artisans, and miners. “It is a curious illustration of democratic equality and republican freedom,” noted one journalist, “to force Juan, who owns not a cent, to fight in defense of Pedro’s property, while the latter declines to raise an arm himself, because he is not so poor as his fellow citizen.”” A large part of the country’s male population lived in fear: farmers refused to bring produce to market; charcoal-burners stayed at home; the young, the infirm, and even the aged – all became targets. In one case, the appearance of recruiters caused a group of inquilinos to jump into a river to avoid capture. Nor was this solely a rural phenomenon. One deputy reported seeing armed soldiers pursue a man down a Santiago street, beat him to the ground, and then march him under capture. Nor was this solely a rural phenomenon. One deputy reported seeing armed soldiers pursue a man down a Santiago street, beat him to the ground, and then march him under the lash to the local barracks.

If some Chileans protested against these activities, others did not – notably those who did not have to serve. Indeed, one particularly patriotic deputy offered to send all of his inquilinos off to war. Occasionally hacendados objected. They did not oppose conscription; they simply did not want their supply of labor disrupted. In one case local landowners decided among themselves who should remain and who should serve. The local newspaper complimented them on their judgment, observing that such actions protected the civil liberties of all.

Once conscripted, a soldier had to accept harsh discipline and endure wretched conditions. Officers and NCOs handed out lashes more liberally than food. Rations themselves were monotonously bleak: hard tack, jerked beef, onions. The military’s supply system often broke down, forcing soldiers to supplement their rations from their own pocket. Not only were the soldiers’ wages low, but the men frequently did not receive their pay because the pay department functioned spasmodically at best, and they often had to write home to ask for money. Garrison life offered only slightly more comfort than the field: isolated in provincial towns, the troops fell easy prey to greedy shopkeepers who watered their liquor and cheated them at every turn.

The Chilean soldier suffered almost as much at the hands of his government as the enemy. Since the Army had economized by abolishing its medical corps, the military had neither the staff nor the facilities to care for the wounded or the sick. While civilians could supply the Army’s need for surgeons and equipment, they could not compensate for the military’s medical incompetence and lack of foresight. General Escala neglected to take ambulances when he attacked Pisagua. Instead of being dealt with in field hospitals, the wounded were often sent back to Chile, sometimes above deck on freighters. As a result, many soldiers arrived home either dead or with gangrenous wounds. Injured soldiers sometimes had to march to the hospitals while enemy prisoners made the same journey by coach. Until protests stopped the practice, government officials insisted that the war-wounded pay for their own medical care; the military also stopped paying a soldier’s wages or family entitlements while he was hospitalized. If the war-wounded merited such cavalier treatment, the war dead received approximately the same veneration as that accorded to a medieval leper. While it is true that the remains of the more conspicuous heroes were deposited in ornate tombs, the less celebrated were dumped naked into graves with indecent haste. This state of affairs became so disgraceful that a Valparaiso workers’ society began to send delegates to accompany each corpse to its final resting-place.

The maimed, and the families of the war dead, fared only slightly better than the dead themselves. The heirs of officers received some protection, but initially the government made no provision to pay pensions to the families of enlisted men. Not until the casualties started to mount, in late 1879, did Congress belatedly address the problem. Its decisions were distinctly niggardly. The mother of a private killed in battle, for example, was awarded 3 pesos per month. Worse still, the pension legislation excluded the survivors of men who died of natural causes or from accidents. Since more soldiers succumbed to the bacillus rather than the bullet, Congress could hardly be faulted for being profligate with taxpayers’ money. Small wonder that patriotism was a luxury in which few Chileans could afford to indulge and that those who did derisively dismissed their rewards, in the time-honored phrase, as el pago de Chile, “Chile’s reward.”