The Chinese military philosopher Sun Tzu said, “He who understands himself and understands his enemy will prevail in one hundred battles.” In order to understand both ourselves and our enemies in Fourth Generation conflicts, it is helpful to use the full framework of the Four Generations of modern war. What are the first three generations?

First Generation war was fought with line and column tactics. It lasted from the Peace of Westphalia until around the time of the American Civil War. Its importance for us today is that the First Generation battlefield was usually a battlefield of order, and the battlefield of order created a culture of order in state militaries. Most of the things that define the difference between “military” and “civilian” – saluting, uniforms, careful gradations of rank, etc. – are products of the First Generation and exist to reinforce a military culture of order. Just as most state militaries are still designed to fight other state militaries, so they also continue to embody the First Generation culture of order.

The problem is that, starting around the middle of the 19th century, the order of the battlefield began to break down. In the face of mass armies, nationalism that made soldiers want to fight, and technological developments such as the rifled musket, the breechloader, barbed wire, and machine guns, the old line-and-column tactics became suicidal. But as the battlefield became more and more disorderly, state militaries remained locked into a culture of order. The military culture that in the First Generation had been consistent with the battlefield became increasingly contradictory to it. That contradiction is one of the reasons state militaries have so much difficulty in Fourth Generation war, where not only is the battlefield disordered, so is the entire society in which the conflict is taking place.

Second Generation war was developed by the French Army during and after World War I. It dealt with the increasing disorder of the battlefield by attempting to impose order on it. Second Generation war, also sometimes called firepower/attrition warfare, relied on centrally controlled indirect artillery fire, carefully synchronized with infantry, cavalry and aviation, to destroy the enemy by killing his soldiers and blowing up his equipment. The French summarized Second Generation war with the phrase, “The artillery conquers, the infantry occupies.”

Second Generation war also preserved the military culture of order. Second Generation militaries focus inward on orders, rules, processes, and procedures. There is a “school solution” for every problem. Battles are fought methodically, so prescribed methods drive training and education, where the goal is perfection of detail in execution. The Second Generation military culture, like the First, values obedience over initiative (initiative is feared because it disrupts synchronization) and relies on imposed discipline.

The United States Army and the U.S. Marine Corps both learned Second Generation war from the French Army during the First World War, and it largely remains the “American way of war” today.

Third Generation war, also called maneuver warfare, was developed by the German Army during World War I. Third Generation war dealt with the disorderly battlefield not by trying to impose order on it but by adapting to disorder and taking advantage of it. Third Generation war relied less on firepower than on speed and tempo. It sought to present the enemy with unexpected and dangerous situations faster than he could cope with them, pulling him apart mentally as well as physically.

The German Army’s new Third Generation infantry tactics were the first non-linear tactics. Instead of trying to hold a line in the defense, the object was to draw the enemy in, then cut him off, putting whole enemy units “in the bag.” On the offensive, the German “storm-troop tactics” of 1918 flowed like water around enemy strong points, reaching deep into the enemy’s rear area and also rolling his forward units up from the flanks and rear. These World War I infantry tactics, when used by armored and mechanized formations in World War II, became known as “Blitzkrieg.”

Just as Third Generation war broke with linear tactics, it also broke with the First and Second Generation culture of order. Third Generation militaries focus outward on the situation, the enemy, and the result the situation requires. Leaders at every level are expected to get that result, regardless of orders. Military education is designed to develop military judgment, not teach processes or methods, and most training is force-on-force free play because only free play approximates the disorder of combat. Third Generation military culture also values initiative over obedience, tolerating mistakes so long as they do not result from timidity, and it relies on self-discipline rather than imposed discipline, because only self-discipline is compatible with initiative.

When Second and Third Generation war met in combat in the German campaign against France in 1940, the Second Generation French Army was defeated completely and quickly; the campaign was over in six weeks. Both armies had similar technology, and the French actually had more (and better) tanks. Ideas, not weapons, dictated the outcome.

Despite the fact that Third Generation war proved its decisive superiority more than 60 years ago, most of the world’s state militaries remain Second Generation. The reason is cultural: they cannot make the break with the culture of order that the Third Generation requires. This is another reason why, around the world, state-armed forces are not doing well against non-state enemies. Second Generation militaries fight by putting firepower on targets, and Fourth Generation fighters are very good at making themselves untargetable. Virtually all Fourth Generation forces are free of the First Generation culture of order; they focus outward, they prize initiative and, because they are highly decentralized, they rely on self-discipline. Second Generation state forces are largely helpless against them.

Fighting Fourth Generation War: Two Models

In fighting Fourth Generation war, there are two basic approaches or models. The first may broadly be called the “de-escalation model,” and it is the focus of this article. But there are times when state-armed forces may employ the other model. Reflecting a case where this second model was applied successfully, we refer to it (borrowing from Martin van Creveld) as the “Hama model.” The Hama model refers to what Syrian President Hafez al-Assad did to the city of Hama in Syria when a non-state entity there, the Moslem Brotherhood, rebelled against his rule.

In 1982, in Hama, Syria, the Sunni Moslem Brotherhood was gaining strength and was planning on intervening in Syrian politics through violence. The dictator of Syria, Hafez al-Assad, was alerted by his intelligence sources that the Moslem Brotherhood was looking to assassinate various members of the ruling Ba’ath Party. In fact, there is credible evidence that the Moslem Brotherhood was planning on overthrowing the Shi’ite/Alawite-dominated Ba’ath government.

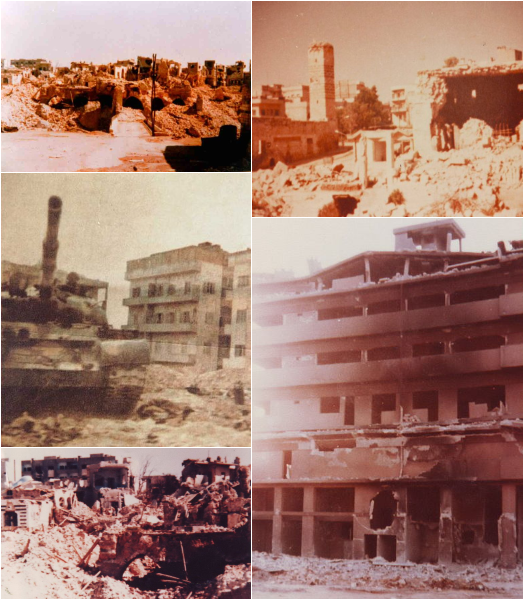

On February 2, 1982, the Syrian Army was deployed into the area surrounding Hama. Within three weeks, the Syrian Army had completely devastated the city, resulting in the deaths of between 10,000 and 25,000 people, depending on the source. The use of heavy artillery, armored forces, and possibly even poison gas resulted in large-scale destruction and an end to the Moslem Brotherhood’s desires to overthrow the Ba’ath Party and Hafez al-Assad. After the operation was finished, one surviving citizen of Hama stated, “We don’t do politics here anymore, we just do religion.”

The results of the destruction of Hama were clear to the survivors. As the June 20, 2000, Christian Science Monitor wrote, “Syria has been vilified in the West for the atrocities at Hama. But many Syrians – including a Sunni merchant class that has thrived under Alawite rule – also note that the result has been years of stability.”

What distinguishes the Hama model is overwhelming firepower and force, deliberately used to create massive casualties and destruction, in an action that ends quickly. Speed is of the essence to the Hama model. If a Hama-type operation is allowed to drag out, it will turn into a disaster on the moral level. The objective is to get it over with so fast that the effect desired locally is achieved before anyone else has time to react or, ideally, even to notice what is going on.

There is little attention to the Hama model because situations where the Western states’ armed forces will be allowed to employ it will probably be few and far between. Domestic and international political considerations will normally tend to rule it out. However, it could become an option if a Weapon of Mass Destruction were used against a Western country on its own soil.

The main reason we need to identify the Hama model is to note a serious danger facing state-armed forces in Fourth Generation situations. It is easy, but fatal, to choose a course that lies somewhere between the Hama model and the de-escalation model. Such a course inevitably results in defeat, because of the power of weakness.

The military historian Martin van Creveld compares a state military that, with its vast superiority in lethality, continually turns its firepower on poorly-equipped Fourth Generation opponents to an adult who administers a prolonged, violent beating to a child in a public place. Regardless of how bad the child has been or how justified the beating may be, every observer sympathizes with the child. Soon, outsiders intervene, and the adult is arrested. The power mismatch is so great that the adult’s action is judged a crime.

This is what happens to state-armed forces that attempt to split the difference between the Hama and de-escalation models. The seemingly endless spectacle of weak opponents and, inevitably, local civilians being killed by the state military’s overwhelming power defeats the state at the moral level. That is why the rule for the Hama model is that the violence must be over fast. It must be ended quickly! Any attempt at a compromise between the two models results in prolonged violence by the state’s armed forces, and it is the duration of the mismatch that is fatal. To the degree the state-armed forces are also foreign invaders, the state’s defeat occurs all the sooner. It occurs both locally and on a global scale. In the 3,000 years that the story of David and Goliath has been told, how many listeners have identified with Goliath?

In most cases, the primary option for state-armed forces will be the de-escalation model. What this means is that when situations threaten to turn violent or actually do so, state forces in Fourth Generation situations will focus their efforts on lowering the level of confrontation until it is no longer violent. They will do so on the tactical, operational, and strategic levels. The remainder of is therefore focused on the de-escalation model for combatting insurgency and other forms of Fourth Generation warfare.