By 1905 the Imperial Russian Navy was a relatively potent force, possessing a powerful battle fleet and with auxiliary squadrons disposed in the farthest dominions of the Tsar. In February 1904 the Japanese attacked the Russians in the Liaotung Peninsula where, in ports leased from the Chinese, they over-wintered their Pacific Fleet. This the Japanese swiftly defeated, and gained the ascendancy, besieging Port Arthur and compelling the Russian High Command to dispatch Admiral Rozhdestvensky’s Baltic Fleet half-way round the world to recover the initiative. Unfortunately Rozhdestvensky was annihilated off the island of Tsu Shima by Admiral Togo in May, and the resulting national humiliation further inflamed an already simmering social unrest in Russia itself.

The defeat of Rozhdestvensky’s fleet was attributed to inefficiency inherent in the privileged system over which the Tsar presided. Because of the war Russia’s finances were in a mess, and hundreds of thousands of lives had been squandered. The civil disturbances occurring throughout the country attracted a severe backlash from the representatives of autocracy, and encouraged those in Russia who sought an overthrow of the traditional and outmoded system of government, any opposition to which was pitilessly crushed. Significantly, the ranks of the navy included a large number of political activists mostly belonging to the Social Democratic Party. A substantial proportion of these were in ships belonging to the Black Sea Fleet, which had taken no part in the Russo-Japanese War and whose morale was already low in consequence of the monotony of their duties and the long periods they lay inactive at their base at Sebastopol. At the end of June the news of Tsu Shima cast a further gloom over this squadron, which was then ordered to sea for gunnery exercises.

The first ship to leave, ahead of the others though escorted by the torpedo boat N267, was the Kniaz Potemkin Tavritchesky, better known to history as the `Battleship Potemkin’. Kapitan II Ranga Evgeny Golikov headed from Sebastopol for Tendra Bay, close to the Romanian border and not far from Odessa, where he anchored his ship. On Tuesday 27 June Golikov was enjoying his lunch when he received a report from his executive officer, Kapitan III Ranga Ippolit Giliarovsky, that the men were in a mutinous mood. The political activists had been seeking a pretext to foment trouble, and it had come to hand in the form of stinking, maggot-infested meat which the men refused to eat. This had been taken on board shortly before the battleship sailed in circumstances which bred a swift-travelling rumour that the contractors were corrupt and the captain and officers had profited from the swindle.

Golikov cleared the lower deck and, having learned that the meat was certified fit for the consumption of the sailors and stokers by Surgeon Smirnov, addressed the crew. Smirnov apparently agreed that the meat had attracted the eggs of some flies, he told them but there were only on the surface and after proper cooking the meat was edible. Golikov concluded by recalling his ship’s company to their duty to the Tsar, and then dismissed them. All might have passed off peaceably, for the majority of the Potemkin’s crew were long-service men who if not docile were certainly not radicals, had not Giliarovsky recalled the muster. Golikov meanwhile had retired to his cabin, unaware that his younger second-in-command had decided to take a harsher line with the mutineers.

Giliarovsky now paraded the ship’s marines under arms, and it is alleged that he ordered a tarpaulin to be spread on the sacred planking of the quarterdeck. Neither the purpose of the tarpaulin nor indeed its actual presence is clear; the horrors of this insurrection were much embellished by the later effects of Sergei Eisenstein’s film, purporting to be documentary in intent but in fact perverse and propagandist. Whether the tarpaulin was there or not, the presence of the marines suggested to the returning seamen that bloodshed might ensue; certainly coercion seemed to be intended. Seeing only Giliarovsky and the armed marines, with no sign of their captain, the men drew the conclusion that some among their number were to be taught a lesson in the prescribed Tsarist manner.

Among them was Afanasy Matushenko, a revolutionary who had been working on a plot to suborn the entire squadron when it arrived at the anchorage. The present situation was clearly too good to waste, and Matushenko called out to the marines not to fire on their shipmates. Others, thought to have been members of Matushenko’s revolutionary cell, tried to disarm the gunners. As they surged forward, Giliarovsky allegedly compounded his high-handed stupidity by firing at one of them, Gunner Grigory Vakulenchuk, who fell mortally wounded. There followed a confused struggle in which a midshipman beside Giliarovsky was also mortally wounded, and an attempt by the gunnery officer, Lieutenant Tonn, to mediate and avert the frightful carnage that seemed about to ensue resulted in his death. With the men’s blood-lust provoked, all sense of reason vanished; revolt against generations of acquiescence, fawning and victimization spread through the Potemkin like fire. As other officers appeared they were shot at; Some who attempted to escape by jumping overboard where exposed to opportunist rifle fire. A handful was picked up by the N267 but most were massacred. Captain Golikov was apprehended and executed; Smirnov was caught in his cabin trying to kill himself. After being brutalized he was killed and thrown overboard. Lieutenant Alexeyev, the navigating officer, was found attempting to reach one of the magazines. Pleading that he was only obeying Golikov’s last orders, he begged for quarter and threw in his lot with the mutineers. He was granted his life on condition that he handle the Potemkin according to the instructions he would receive.

As Kapitan III Ranga Baron von Jurgensburg attempted to steam the N267 out of the Bay and out of range, his vessel received a shot from the Potemkin’s secondary armament. Intimidated, he brought his torpedo boat back alongside the battleship where he, his own officers and those he had rescued were secured in custody aboard the Potemkin.

The vast majority of the Potemkin’s crew had taken no part in the mutiny, though many were mute and astonished witnesses. As the situation gained momentum they stood stupefied by Matushenko’s oratory. From atop the capstan so recently vacated by Golikov, the revolutionary harangued them: they were heroes; they had lit the torch of revolution and were the first to throw off the chains of slavery. Soon they would carry the whole squadron with them, and then join their comrades ashore. It was heady and inspiriting stuff.

Matushenko was now in command, with Alexeyev ready to navigate the ship towards Odessa, a few miles along the coast, and Engineering Lieutenant Kovalenko, a Marxist sympathizer, keen to provide the motive power. At Odessa it was planned to make contact with revolutionary elements which were fomenting daily confrontations between strikers and the Tsarist forces. In addition to the police, the latter included Cossacks under General Kokhanov, the local military commander.

The arrival of the Kniaz Potemkin Tavritchesky off Odessa that evening flying the red flag encouraged the forces of reform and revolution. A student leader named Constantin Feldmann came aboard at the head of a group of ardent socialists. Learning of the death of Gunner Vakulenchuck in the night and of the desire of his shipmates to give him a suitable funeral, Feldman suggested that his body be landed as a symbolic act about which the revolution might coalesce. Most of the Potemkin’s bewildered crew merely wanted Vakulenchuk properly buried. As happened in most mutinies, once the heat of the insurrectionary moment had passed, there was a sense of rudderless impotence. If not exactly a political reaction, it was enough to persuade a disappointed Feldmann and his colleagues not to expect much from the Potemkin. The battleship’s presence offshore was stimulating enough, however, and when Vakulenchuk’s body was landed next day at the foot of the Richelieu steps it attracted sufficient popular attention to provoke Kokhanov into ordering the Cossacks to clear the crowds. Eisenstein is believed to have grossly exaggerated what followed; nevertheless few authorities entirely write off the event as anything other than `a massacre’. (In the so-called `Boston massacre’ of March 1770, be it recalled, British infantry actually killed only three and wounded two people.) Dismounting from their ponies, the Cossacks descended the wide steps firing over the heads of the assembly and then, as the populace appeared defiant, into the body of the crowd. Kokhanov claimed the dead to number 500, while the total number killed in Odessa over several days is put ten times higher.

Throughout the 28th Matushenko received demands from the shore that the revolutionaries aboard should assist the townspeople by opening fire with their guns, but he demurred. All would be well when the rest of the squadron arrived, he assured them though what exactly he meant by this he did not say. In the meantime the Potemkin had been taking coal aboard; that done, her crew had been subjected to further haranguing by Feldmann. As time passed, none of the rest of the Black Sea squadron arrived – only the solitary auxiliary Vekhia, bearing Golikov’s widow and heir. In a hiatus that day, Vakulenchuk’s body was buried by a dozen unarmed seamen, who were fired at by the Cossacks as they made their way back to the Potemkin’s boats; three of them were killed.

Matushenko’s confidence in his fellows aboard the other ships of the squadron was misplaced. At Sebastopol, in the temporary absence of the Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Chukhnin, Vitse Admiral Krieger had learned of the defection of the Potemkin and ascertained the loyalty of the rest of the squadron. Ordering one ship to remain at her moorings, Kontr Admiral Vishnevetsky was to take three battleships, one cruiser and four torpedo boats to Odessa to overwhelm the mutineers, Krieger prepared to follow in his flagship, the Rostislav. Off Odessa the loss of some of the burial party focused the attention of the Potemkin’s crew on the shore. Feldmann’s blandishments were one thing, the death of their own comrades quite another. Informed that a meeting of the Tsarist military was to take place in the theatre at 19.30 that evening, the Potemkin’s secondary armament fired two blank warning shots and two live rounds. The latter landed wide and killed only more citizens; it was bathetic. Word had also arrived that the Black Sea Fleet was on its way.

Next morning Matushenko and his committee, along with Feldmann, saw the smoke of the approaching squadron. The hands were piped to their stations and the anchor was weighed. Alexeyev was ordered to head towards Vishnevetsky and the Potemkin’s guns were manned. Whether the Russian admiral doubted the temper of his men or feared the potency of Matushenko’s gunners is unclear. What is certain is that he turned away and headed for Tendra Bay `to await reinforcements’, presumably Admiral Krieger and his flagship. He earned himself a severe reprimand, but he met Krieger, who had brought another man-of-war with him in addition to the Rostislav. Forming two divisions, the Black Sea squadron next headed back towards Odessa. Here its approaching smoke signalled the end of a performance by the ship’s band on the quarterdeck of the Potemkin which, having seen off Vishnevetsky, had re-anchored off Odessa.

Once again the mutineers weighed anchor, manned their guns and steamed towards the advancing columns. Receiving a radioed demand to surrender, Matushenko told Alexeyev to maintain course and speed, sweeping aside the cruiser Kazarsky which was acting as advanced picket. What happened next was worthy of Eisenstein’s drama; the men on most of the opposing ships poured out of their gun turrets and abandoned their battle stations to cheer the Potemkin as she passed between them. Krieger, Vishnevetsky and the other captains and officers could only wring their hands in frustration. When the Potemkin had passed through the lines, Alexeyev turned her about and overtook the squadron, heading back towards Odessa. As Krieger ordered the squadron to turn away, the battleship Georgi Pobjedonosets (George the Conqueror) followed in Potemkin’s wake, anchoring in company off Odessa a little later.

Matushenko and Feldmann went aboard her only to find that the mutiny aboard the second battleship was incomplete: parts of the ship were in loyalist hands and the petty officers were resisting the demands of the revolutionaries. Feldmann talked himself hoarse convincing the waverers, and by the following dawn the revolutionary `fleet’ appeared to consist of the two battleships, the N267, the storeship Vekhia and a collier from which the Potemkin had bunkered.

This was an illusion. The following morning the Georgi Pobjedonosets was in fact uncommitted, and further attempts to suborn her failed. In the end her anchor was weighed and she headed for the inner harbour of Odessa, only to ground on a shoal, and afterwards to beg forgiveness from the Tsar. By now General Kokhanov had called up artillery and the heights above the town were invested with heavy guns. Taking the city was impossible, and with every hour that passed the men aboard the Potemkin became increasingly disillusioned. They knew what the regime would do to them if they submitted. For those in any doubt there was the example of the fate of the protesters of Bloody Sunday, who in the previous January had gone peacefully to present a petition to the Tsar at the Winter Palace in St Petersburg. They had been shot down for their pains, and 130 of their number killed. While unwilling to prosecute the revolution so fervently called for by Matushenko and Feldmann, the majority knew that surrender meant death, or exile in Siberia. Not even rotten meat could persuade them to martyr themselves; instead they would head for the Romanian port of Constanza.

Hearing of Krieger’s humiliation on his return to Sebastopol, Admiral Chukhnin complained that `the sea is full of rebels’ and sanctioned Lieutenant Yanovitch’s wish to lead an attack by volunteer officers in the destroyer Stremitelny to avenge the deaths of their colleagues. Filled with zealous young bloods, the Stremitelny left after dark on 1 July but arrived off Odessa to find that the Potemkin and the N267 had slipped away some hours earlier.

On their arrival off Constanza the mutineers aboard the Potemkin appealed to the Romanian authorities for water, fuel and stores, but King Carol’s government repudiated any notion of offering them sanctuary. Disappointed, the Potemkin and the N267 put to sea again, avoiding the approaching Stremitelny and the battleships Sinop and Tri Sviatitelia, whose officers had persuaded their crews to remain loyal and do their duty.

Enclosed in a land-locked sea as she was, the Potemkin’s fate was now sealed, but Matushenko and his men were not yet ready to give up. Short of water they headed out to sea, bypassing Sebastopol and their hunters. In company with the little torpedo boat N267 they headed for Feodosia, on the far side of the Crimean peninsula from the Russian naval base. On board the daily routines went on, supervised by the petty officers, while Feldmann dreamed up revised plans for taking the revolution to the Chechens of Caucasia. When the battleship arrived off Feodosia, the ship’s ruling committee was welcomed, but only fresh water was offered them. Matushenko responded by demanding coal and food as well, or the battleship’s guns would blow the small town off the face of the globe. As the townsfolk fled to the hills Matushenko and Feldmann took a party of men to seize a coal hulk, and were fired upon by an infantry foot patrol. Three seamen were killed as the rest leapt back into the Potemkin’s picket boat and headed for their ship. Rifle-fire followed and another man was hit and fell into the water with a cry; courageously Feldmann dived after him. The picket boat steamed on, and a few minutes later a boat was pulled out from the shore to capture Feldmann and the wounded sailor.

For Matushenko and the others hell-bent on revolution the game was all but up, for now the Stremitelny arrived: failure, exile and death confronted them. Their vision of social justice was extinguished, and the Black Sea was `watered by our tears’. Only a breakdown in the Stremitelny’s steam-turbines prevented the affair ending then and there, but once again an element of farce prevailed. The Potemkin and her consort again escaped, weighing anchor and steaming away, to arrive off Constanza again on 8 July. Here the committee decided to scuttle the ship, and those of her crew who wished to do so were allowed to land, and gave themselves up to the Romanians. About five hundred were suffered to stay, and the Romanian government eventually rejected Russian attempts at extradition, on the grounds that the seamen’s act had been political, not criminal.

Some of these men found themselves caught up in a Romanian peasant revolt in 1906 and were subsequently deported to Russia, where the authorities promptly sent them into exile; some returned to Russia under an amnesty, only to find themselves tried, condemned and exiled like the others; a few emigrated to Britain and Argentina. But not all the Potemkin’s crew had followed Matushenko: about three hundred surrendered to the Russians, who almost within hours finally caught up with the Potemkin. Courts-martial condemned seven of those remaining to death; nineteen others received life sentences in Siberia, a further thirty-five long penal sentences. Incredibly, Alexeyev and the handful of surviving officers, pleading that they had been obliged to do as they were bid to save their lives, were exonerated. Feldmann later escaped from prison to Austria, and is today remembered in Odessa, where after the successful Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 the Nikolaevsy Boulevard was renamed in his honour.

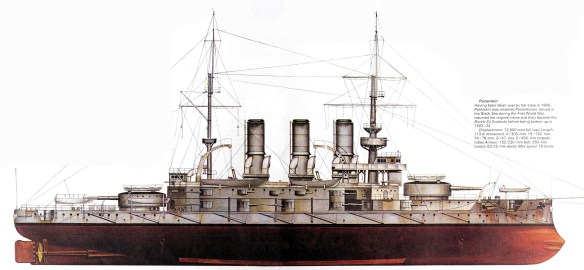

As for Matushenko, he evaded the Ochrana’s agents in Romania and headed for New York where he worked for some time, associating with Russian emigre radicals and caught up in revolutionary fervour. In 1907 he foolishly returned to Russia using false papers, only to be recognized, tried and hanged at Sebastopol. As for the ship whose name is better remembered than those of any of the human participants, except perhaps the `martyred’ Vakulenchuk in Russia, the tragi-farcical nature of the mutiny aboard the Kniaz Potemkin Tavritchevsky was not at an end with her scuttling. Even this was botched. By 11 July the water had been pumped out of her, she had been re-floated, and the Imperial Russian naval ensign of St Andrew’s cross was re-hoisted. Taken in tow by the Tri Sviatitelia (the Holy Trinity) she was taken back to Sebastopol, where in October she was renamed Pantelymon – meaning a peasant of the most humble stock – and remained inactive throughout the First World War. Then, in 1919, as the tide of revolution closed on the Crimea, Tsarist officers scuttled her a second time, to prevent her falling into the hands of the Bolsheviks. Her final and lasting resurrection was in 1925, when to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of what Soviet historians came to call the First Bourgeois-Democratic Revolution Sergei Eisenstein made his celebrated film of the incident, dramatizing the events in five sequences that have, like his storming of the Winter Palace, come to be regarded as reality itself.

In reality there was no stirring climax, only the end common to most mutinies – failure. Such is the power of the moving visual image, however, that the mutiny aboard the `Battleship Potemkin’ is as well-established a myth as that aboard the Bounty. Perhaps the most interesting fact about the mutiny aboard the Kniaz Potemkin Tavritchesky is that it established itself as a key event solely because it coincided with the civil unrest in Odessa, circumstantially linking mutiny with social change. What had its genesis in a specific, traditional ship-board complaint about bad food has become a defining moment in the great move for social change and the advancement of the less well-off. The first mutinies, those against Magellan and Drake, were about command, fomented among those vying for high office. Later, exemplified by the masterly revolt at Spithead, they concerned genuine grievances, only to be followed by a degenerate series of cathartic expressions of discontent, envy and malice on the path of minorities challenging an inadequate command structure backed by law and usage, neither of which proved of the slightest use when mutiny actually occurred. With the possible exception – which if anything proves the general rule – of some evidence of political agitation at the Nore, the mutiny aboard the Potemkin marks another shift in gear; it is the first mutiny to become indissolubly linked with a greater social movement and a more general aspiration for real change, as opposed to a redress of complaints.

Had not the ship anchored off Odessa, and had not the indefatigable Feldmann and his associates clambered on board full of revolutionary zeal, it is unlikely that the Potemkin mutiny would have acquired this iconic status. As was so often the case in earlier mutinies, it is clear that Matushenko and his colleagues had little idea what to do once they had seized the ship, committed murder and placed themselves outside the law. Any ray of hope that might have been kindled by the ambiguous conduct of the Black Sea squadron under Kontr Admiral Vishnevetsky soon evaporated. The indifference or confusion of the majority of the Potemkin’s crew as to what was going on suggests that in due course the affair would have fizzled out, as it did on the Georgi Pobjedonosets.