In 1814, Major General Robert Rollo Gillespie died in the Battle of Kalunga in the Anglo-Nepalese War. From the mid-eighteenth century onwards, the Kingdom of Nepal had become increasingly expansionist, as its powerful military forces pressed westwards into the Punjab and eastwards into Tibet. The Gurkha army, though not large, combined European-style discipline with a toughness bred from living in some of the world’s most rugged terrain. By the early nineteenth century, a collision between Nepal and an equally expansionist East India Company was inevitable. The flashpoint came at Oudh (or Awadh, today in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh), one of India’s wealthiest and most fertile provinces, which shared its northern border with Nepal and which the Nepalese had long coveted. The British had controlled half of Oudh since 1801, while the other half remained under the nominal control of the nawab, in reality a British puppet. Tension mounted over the control of disputed villages along the border, and in 1814 war broke out.

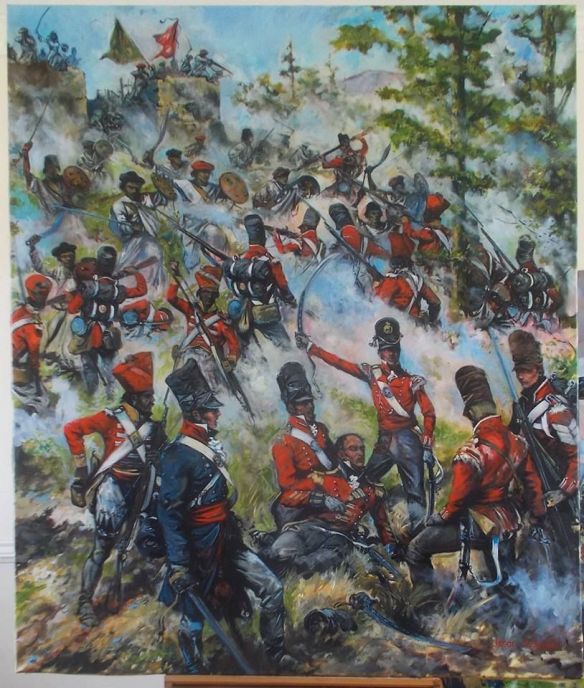

The British had 21,000 men available to send north, twice the number that military experts estimated were necessary to defeat the Gurkhas. The campaign, however, presented unique challenges due to the terrain and weather. The British advanced in four columns, a strategy that was intended to achieve a swift victory by cutting off the Gurkha army from Kathmandu. Led by Gillespie, the easternmost column had as its first objective the hill fort at Kalunga (called Nalapani by the Gurkhas), which protected the route west across the Dehra Dun from Srinigar. Garrisoned by six hundred Gurkhas, Kalunga was a formidable obstacle, but Gillespie was confident in the ability of his artillery to blast a breach in the walls and of his numerically superior force to take the fort quickly. He divided his force of 4,500 into four columns, which were to attack simultaneously two hours after hearing a prearranged signal. Gillespie’s final order stressed the importance of `cool and deliberate valour’ over `wild and precipitate courage’, though he was to ignore his own advice, with fatal consequences. On the morning of 31 October, the artillery opened up at daybreak, but the guns were too far away to inflict significant damage. The main attack was not supposed to occur until noon, but just before nine, a party of Gurkhas attempted to take some of the British guns. They were quickly repulsed, but when Gillespie saw them heading back towards the fort, he sent messages to the commanders of the other columns, ordering them to attack immediately. The columns were impossible to locate quickly in the rugged terrain, however, and none of the messages reached its destination in time. Gillespie’s own column charged forward nonetheless, and were met by Gurkhas who swarmed over the walls of the fort to meet them. The attack rapidly lost momentum as the Gurkhas wielded their kukris, or curved knives, with devastating effectiveness in hand-to-hand combat. Fifty-eight dragoons were slaughtered within minutes.

Frustrated and unable to countenance even a temporary defeat, Gillespie declared his intention to take the fort there and then or to be killed trying. One of his officers had spotted a small gateway in the side, and he now focused his attention upon it, despite the fact that it was heavily defended. After a six-pound gun was brought up but failed to clear the gate, Gillespie tried to convince his men to attack it from the flanks. Recognizing that this was suicidal, they refused to follow him. Gillespie charged forward anyway and was shot in the chest. He died almost immediately. The attack collapsed, and it would take another month for the British to capture the fort. It was not until the garrison was almost completely out of food, water and ammunition that it slipped away under cover of darkness. When the British entered the fort, they discovered that 520 of the six hundred Gurkha defenders had been killed, or were so badly wounded or weak from starvation that they could not escape with the survivors.

Gillespie’s actions had been foolhardy, as the governor general of India, Lord Hastings, recognized. On 10 November, he wrote to Lord Bathurst, secretary of state for war and the colonies, that

the good fortune which had attended him in former desperate enterprises induced him to believe, I fear, that the storm of the fortress of Kalanga might be achieved by the same daring valour and readiness of resource whereby he had on other occasions triumphed over obstacles apparently insuperable. The assault in which he was killed at the foot of the rampart, involved, as I conceive, no possibility of success; otherwise the courage of the soldiers would have carried the plan notwithstanding the determined resistance of the garrison.

As more details became known, however, it emerged that the soldiers from the 53rd Regiment had refused to follow Gillespie in his attack on the gateway. Feeling guilty about maligning the conduct of a brave officer who had died in battle, Hastings now began to sing Gillespie’s praises. The prevailing view of his actions shifted accordingly: Charles Metcalfe, British resident in Delhi, wrote in 1815 that `the gallant Gillespie would, I am sure, have carried everything, had he not been deserted by a set of cowardly wretches’.

Back in Britain, where Gillespie was regarded as a colourful and popular soldier, the news of his death occasioned an outpouring of grief. He was the subject of a fulsome memoir which held him up as an example to future generations: `So long . . . as military virtue shall be held in esteem, and so long as our national history shall be read with pride and emulation, so long will the name of this heroic character be mentioned with enthusiasm, and his exploits pointed out as examples of imitation.’ Instead of leading an ill-advised attack, he was pictured as having made a gallant attempt to pull victory from the jaws of defeat:

The general considered it to be his duty to expose himself in the most conspicuous manner, that, if possible, his example might inspire and rouse the emulation of his troops into another vigorous and effectual attack upon the place. The heroic sentiment which occasioned this sacrifice has carried the renown of the British arms to a height of splendour, that, in point of radical virtue, and permanent utility, has far exceeded the Grecian and Roman glory. That daring spirit of bold enterprize, which in Europe has stamped with immortality so many illustrious names, will be found particularly needful in the vast and complicated regions of the East, where, from the character of the people, and the tenure of our possessions, we shall be continually obliged to maintain a high military attitude.

The author also included a hagiographic poem about Gillespie by `an amiable and accomplished lady in this country’ that sought to inspire Britons to follow his example:

These tender tears, to cherish’d virtue due,

This unavailing flood of genuine grief,

Gillespie! Shall thy sacred name bedew,

And give fresh verdure to each laurel leaf.

But ye who mourn the honor’d hero’s death,

Arouse from woe, and lead the life he led;

Practise his virtues till your latest breath,

To be like him illustrious when ye’re dead.

An impressive column was erected over Gillespie’s grave in Meerut, and in 1820 a statue was installed in St Paul’s Cathedral. Though it took three decades, a group of local grandees in his native town of Comber in County Down collected funds for a memorial in the form of a 55-foot-high (17 m) column topped by a statue of the dead hero. It was unveiled in 1845 before a crowd of 25,000 people.

Gillespie’s actions at Kalunga were undeniably foolhardy. Even so, he became a hero. Why? There were a number of reasons. First, he was already a famous soldier who had fought in the West Indies, India and Java, playing key roles in the suppression of the mutiny at Vellore in southern India in 1806 and the conquest of the Dutch city of Batavia in 1811. A diminutive man with an outsize personality, he was known among his acquaintances for his drinking, gambling and debauchery, but at a distance he seemed a merely colourful and courageous figure. The most important reason for Gillespie’s posthumous fame, however, was provided by the context in which his death took place.

The war against the Gurkhas in which Gillespie died was another bloody and hard-fought struggle. On the one hand, his death reassured the British that, led by such brave commanders, their military forces would ultimately prevail, even if it took longer and cost more soldiers’ lives than they initially expected. And, on the other, it reassured them that their efforts to bring more of India under the authority of the East India Company – an entity that could be seen as profitable far more readily than it could be seen as benevolent – represented a fair fight rather than a one-sided affair in which a despotic power was crushing anything and anyone that dared stand in its way