The ability of death in warfare to create a hero from even the most unpromising circumstances was demonstrated by the examples of Major Generals Sir Edward Pakenham and Samuel Gibbs, who died in 1815 at New Orleans in the final battle of the War of 1812. A memorial statue in St Paul’s Cathedral by Richard Westmacott shows the two men standing side by side, with Gibbs leaning on Pakenham’s shoulder in a display of fraternity and calm resignation in the face of adversity. The inscription records that they `fell gloriously on the eve of January 1815 while leading the troops in an attack of the enemy’s works in front of New Orleans’.

In reality, there was little that was glorious about the deaths of Pakenham and Gibbs. Pakenham had previously fought brilliantly in the Peninsular War – Wellington credited his daring flanking manoeuvre as being responsible for his victory at Salamanca – but he had not wanted to go to America to fight in a conflict that few Britons understood or cared about, while Napoleon was still on the loose in Europe. His misgivings were not assuaged by his initial assessment of the situation at New Orleans, as the swampy landscape made the swift and unified movement of troops all but impossible. But knowing how difficult it would be to move the army to another position, Pakenham reluctantly agreed to go ahead with the plan of attack drawn up by Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane, the commander of the British naval forces. On the morning of 8 January 1814, the British troops were forced to cross a mile of flat, open, marshy ground as the Americans fired at them from behind a mud-and-log rampart. Their discipline and courage might still have secured victory, but a misunderstood order meant that they had not brought the ladders required to scale the rampart. As the carnage mounted, some men refused to advance, and Pakenham galloped to the head of his lines to try and rally them. Lieutenant George Robert Gleig described what happened next:

Poor Pakenham saw how things were going, and did all that a General could do to rally his broken troops. Riding towards the 44th which had returned to the ground, but in great disorder, he called out for Colonel Mullens to advance; but that officer had disappeared, and was not to be found. He, therefore, prepared to lead them on himself, and had put himself at their head for that purpose, when he received a slight wound in the knee from a musket ball, which killed his horse. Mounting another, he again headed the 44th, when a second ball took effect more fatally, and he dropped lifeless into the arms of his aide-de-camp.

This was not quite accurate: Pakenham was carried from the field still alive, but barely. He died under a tree a few minutes later, only thirty-six years old.

Pakenham’s death left his second-in-command, Gibbs, in charge of the battle. He, too, made a desperate attempt to rally the troops, charging to within 20 yards (18 m) of the American front line. There, he too was shot, and he died the next day. The third-in-command, Lieutenant General John Keane, was severely wounded but survived. For the British, the Battle of New Orleans was a debacle: 291 men were killed, 484 taken prisoner and 1,262 wounded, adding up to 2,037 total casualties; three generals and eight colonels and lieutenant colonels died. A mere thirteen Americans were killed. 4 Gleig was stunned when he rode over the battlefield after a temporary truce had been declared a few days later:

Of all the sights that I ever witnessed, that which met me there was beyond comparison the most shocking, and the most humiliating. Within the small compass of a few hundred yards, were gathered together nearly a thousand bodies, all of them arrayed in British uniforms. Not a single American was among them; all were English; and they were thrown by dozens into shallow holes, scarcely deep enough to furnish them with a slight covering of earth. Nor was this all. An American officer stood by smoking a segar [sic], and apparently counting the slain with a look of savage exultation; and repeating over and over again to each individual that approached him, that their loss amounted only to eight men killed, and fourteen wounded. I confess, that when I beheld the scene, I hung down my head half in sorrow, and half in anger.

To make matters worse for the British, the Treaty of Ghent ending the War of 1812 had been signed on 24 December, two weeks before the battle.

New Orleans was a shocking defeat. A month before the battle, Colonel Frederick Stovin, assistant adjutant general to the British army, had been breezily confident. Writing to his mother from aboard HMS Tonnant, Admiral Cochrane’s flagship, he bragged: `I have no doubt of our success, for although the Americans are quite aware of our intentions I do not believe they can collect above 3 or 4000 men to oppose us and we have 6000 – theirs inexperienced and undisciplined; ours perfect soldiers and in the habits of victory.’ Afterwards, his attitude was very different. He had been wounded in the neck, but was most devastated by the loss of his `inestimable friend’ Edward Pakenham: `It has almost unhinged me and given me a distaste [for] the service on which we are employed.’ His disparagement of the Americans had vanished; he now found it to be `truly repugnant to fight against people who speak the same language, many of whom are really your countrymen and . . . claim their origins so immediately from your own soil’.

Why, then, instead of quickly burying their embarrassing defeat at New Orleans, did the British choose to grant Pakenham and Gibbs the very visible honour of a memorial statue in St Paul’s? To answer this question, we first need to take into account that military martyrdom held a powerful cultural appeal in the early nineteenth century. From a British perspective, martyrdom was particularly powerful when it involved men of elevated social status like Pakenham and Gibbs. This period saw the emergence of a new emphasis on duty as a social and cultural ideal among the British elite, as the upper classes responded to pressure for parliamentary reform and increased democracy by promoting a new image of themselves as a `service elite’ dedicated to supporting the national interest. This fresh dedication to duty often manifested itself in the form of military and naval contributions, thereby providing a justification for continued upper-class domination of wealth, status and power in Britain. In assessing the heroism of elite officers like Pakenham and Gibbs, it was of little significance that they had lost the Battle of New Orleans, especially since the defeat had occurred in a war that had minimal consequences for British power or prestige. What mattered was their willingness to serve and the fact that they had laid down their lives for their country. The fact that their deaths occurred as they tried to rally their troops from a catastrophic defeat only threw the heroism of their actions into higher relief.

To comprehend fully the heroism of Pakenham and Gibbs as it was culturally defined in the early nineteenth century, however, we need to take into account the broader context of the relationship between Britain’s military forces and civil society in the first half of the nineteenth century. In this era, though many Britons took pride in the army when it won important victories, they also feared it as a potential source of repression and tyranny and believed that, in peacetime, it should be kept as small as possible. They also had little regard for common soldiers; Wellington’s description of them as the `scum of the earth’ encapsulated the predominant popular perception. For much of the nineteenth century, the army was an object of both suspicion and contempt.

Both the elite who filled the officer ranks and the government who relied on the army to win the war against Napoleon had a strong interest in overcoming this distrust of a strong military. One strategy they used was to elevate martyrs who died in battle, who acted as reminders of the patriotic and benevolent nature of the armed forces.

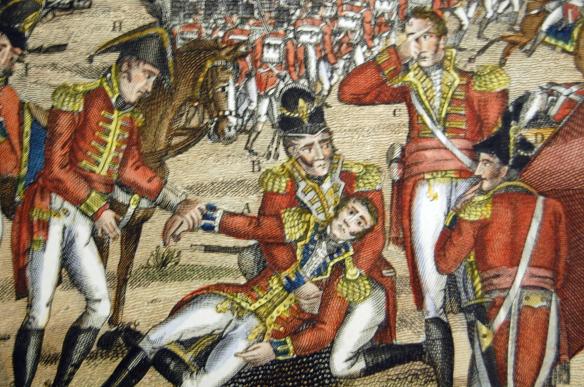

Another example of a contemporary mode of representing military leaders who had fallen in the moment of victory. This mode had evolved from Benjamin West’s painting The Death of General Wolfe (1770), which depicted the death of General James Wolfe at the Battle of Quebec in 1759. West’s painting was immensely popular: King George III commissioned a copy, and an engraved print was a tremendous popular success. The Death of General Wolfe influenced British martial art for decades afterwards: many subsequent depictions of death in battle featured a prostrate hero at the centre of the composition, with the action raging around him and with his most prominent officers looking on mournfully as he expired. These paintings were rarely historically accurate, but they were not supposed to be. Instead, they were intended to convey the sorrow occasioned by the death of a great hero, as well as to ensure that his demise was surrounded by appropriate ceremony and recognition of its significance.