For the Royal Navy, there was no more demanding station than the East Indies. The command stretched over an enormous area, amounting to almost 29 million square miles from the Cape of Good Hope in the west to Manila in the east, which made locating enemy forces and coordinating operations incredibly difficult. On one occasion in 1805, two British fleets spent months sailing around the Indian Ocean in an attempt to combine forces, only to keep missing each other. It followed that protecting British trade against enemy predations was a severe challenge, made harder still by the paucity of resources devoted to the region. In July 1803 the naval force amounted to a mere nine vessels and it was not until the following year that the fleet began to reach a respectable size. Moreover, all merchant ships entering and leaving the region travelled along a precarious trade route, forced to negotiate enemy privateers based at the French ports at Ile Bonaparte (formerly Ile Bourbon, and nowadays Réunion) and Ile de France (Mauritius). The defence of British commerce was complicated further by the monsoon, which created specific windows in which trade could enter and leave the region, seasonal restrictions that were well known to the watching French squadrons as they waited to attack British shipping.

The navy was further hampered by poor charts, uncooperative merchants and the ever- present threat of fever. Between 1806 and 1810, over a thou- sand men died of disease, and the navy was forced to resort to large- scale impressment from merchant ships to make up the deficiencies in manpower. Perhaps the greatest challenge, though, was the vast distance between a fleet in the Indian Ocean and the Admiralty in London. Naval commanders were often operating with information months out of date and with no clear idea as to what the Admiralty wished them to do. A letter sent by sea took between four and five months to arrive, while the passage by land through Turkey and the Middle East was fraught with its own dangers. Put simply, it took an awfully long time for messages to reach India and even longer when enemy fleets were cruising in the Indian Ocean: one message sent late in 1803 took eleven months to arrive. Naval commanders did correspond with the Admiralty but essentially they were left to their own devices, forced to judge situations and make decisions without recourse to a higher authority. As a result, the war in the East remained remote and isolated from the rest of the naval conflict.

Such was the distance that even declarations of war could take months to arrive. July 1803 found Admiral Peter Rainier gazing expectantly into the port of Pondicherry, an unfortified harbour on the south- east coast of India. Anchored inside was a French fleet that had sailed to the Indian Ocean during the Peace of Amiens under the command of Charles- Alexandre Durand Linois. For two months, Rainier received unconfirmed rumours that war between Britain and France had resumed, but without official authorisation he refrained from attacking. Rainier had commanded the East Indies station for eight years, a role that had made him an incredibly rich man: at his death his property was valued at nearly a quarter of a million pounds, an astonishing sum even by standards of naval prize money. By 1803 he was eager to come home and had already attempted to resign his position once before. With his unparalleled knowledge of the region, however, the Admiralty was reluctant to allow him to return, and insisted that he remain in command. On the night of 24 July, correctly anticipating the news of war, the French squadron slipped past his fleet and put to sea. Rainier was left scrabbling. `At Daylight I sent ships out in different directions to observe what course he had steered,’ he wrote to the Admiralty, `but none of them were able to get sight of him.’ Not until the end of August did the news of war reach Rainier, by which time Linois’s fleet had disappeared into the vast Indian Ocean.

Linois’s escape struck at the heart of Britain’s trading empire. Since the loss of the American colonies, the East Indies had become a region of great commercial opportunity, while trade with India and China had grown rapidly in the late eighteenth century. In 1803 it accounted for £6.3 million of British imports, more than that of any other region of the world. It was of vital importance to the British government’s execution of the war, for the revenue generated by trade brought vast fiscal resources into the nation’s coffers. In 1803 the revenue on tea alone was worth £1.7 million to the Treasury, enough to cover a sixth of the entire naval budget. This commerce was conducted exclusively by the leading trading organisation of its time, the East India Company, which governed British trade across the Indian Ocean. Although a semi- private company, it effectively ruled and administered large stretches of India, its power centralised in three presidencies at Madras, Bombay and Calcutta, with a further outpost at Penang. The Company acted as a state in its own right, funding a private army to back up its interests, and also supported a small naval force known as the Bombay Marine. This was insufficient for the Company’s needs, however, and the Royal Navy was therefore charged with protecting the region’s vast coastline from French incursions, while also defending the Company’s seaborne commerce.

The unique nature of the East Indies station provoked contrasting emotions among the officers and sailors posted to the region. As Rainier’s bank balance could attest, there was considerable prize money to be made, and for others the exotic East promised novelty and adventure. Robert Hay, a sailor on board Culloden as it voyaged to the East Indies in 1804, was initially fascinated by what he encountered:

`The appearance of everything here was new and strange,’ he later wrote. Not everyone, however, was so enthusiastic and even Hay himself began to have second thoughts: In these warm climates, men have a much greater number of enemies to annoy them than in the more temperate regions. The first and minutest, though not the least troublesome, is the mosquito . . . as soon as the shades of night set in, they begin their depredations, and woe to every inch of human skin exposed to the attacks, especially that of newly- arrived Europeans, whose face, after sleeping ashore on the first night, may be so disfigured as to be scarcely recognisable by his most intimate acquaintance.

Some of those with prior experience of the region took the opportunity to switch command: Lieutenant Hawkins of Culloden was `not fond of India’ and transferred to a ship on a home station after discovering its destina- tion. It was for precisely this reason that the Admiralty was determined that the experienced Rainier should remain on station, at least until a suit- able replacement could be found. With Linois’s fleet loose in the Indian Ocean and capable of striking at any of Britain’s Indian possessions, Rainier was attempting to find a needle in a haystack. The Commander- in- Chief was faced with a difficult choice: he could concentrate his resources on protecting Company trade or arrange them to defend Britain’s Indian possessions, but his limited means meant that he was unable to do both. Frustrated by this dearth of resources, he was forced to explain to the Governor- General, the Marquis Wellesley, that he had no spare ships to chase Linois. Rainier organised his fleet to defend what he believed were the weaker parts of the Indian coastline, at Goa, Bombay and Trincomalee, while a small detachment of a frigate and two sloops was sent under Captain Walter Bathurst to protect Madras. Rainier kept together his four ships of the line, which included the 50- gun Centurion, to repel any surprise French incursions. In the face of this limited force, over the next two and a half years Linois’s squadron proved a persistent and aggressive adversary, attacking trade and raiding British settlements, returning each winter to its base at Mauritius. Faced with such a nimble and elusive foe, Rainier was constantly playing catch-up.

The French threat was quickly made clear. Having escaped from Pondicherry in July, Linois had headed south to Ile de France, where he finally confirmed that war had been declared. On 8 October, Linois put to sea with the warship Marengo, two frigates, Belle Poule and Simillante, and the corvette Berceau, and headed north once again. He was well aware of his operational advantage over Rainier. As he explained in 1803, `there are many points to guard, their forces must be greatly stretched. That gives me hope to do them much harm by moving the great distances within the different parts of the Indian Seas.’ The French ability to attack suddenly, and with devastating effect, was demonstrated on 2 December 1803, when Linois’s squadron descended unexpectedly on Sumatra, sailing into Bencoolen harbour. Flying British colours until the last minute, the squadron caught the British unprepared and completely fooled them – the garrison even sent out a pilot to help navigate the fleet into port. Two prizes were taken and five merchantmen burnt, while landing parties set fire to the warehouses. Having wreaked havoc, Linois escaped to the safety of the nearby Dutch colony of Batavia. Rainer did not hear of the raid until two months later, by which time Linois was long gone.

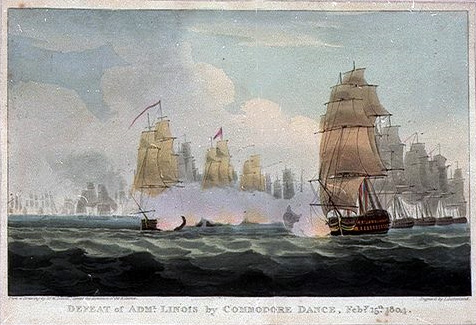

Rainier’s limited resources also meant that the annual China convoy, which carried vast quantities of tea to Britain, sailed on 31 January 1804 without a naval escort. It left with 27 poorly armed Indiamen, carrying a cargo worth £8 million on board. It was an easy target for the French, and at daybreak on 14 February it was intercepted near the eastern entrance of the Strait of Malacca by Linois’s squadron. In a bluff that was as brave as it was fortunate, the convoy’s commander, Nathaniel Dance, steered straight for the French with his ships in a line- of- battle formation and ordered them to fly the naval ensign. He hoped to fool the enemy commander and, as luck would have it, Linois had received erroneous intelligence that British naval forces were in the region. Believing the Indiamen to be ships of the line, he delayed further action until the next morning. Having finally attacked, a brief and confused engagement of forty minutes convinced Linois that he was up against warships, and he made the terrible decision to haul off. Determined to maintain the pretence, Dance signalled a general chase after the retreating foe, and Linois was completely deceived. The Battle of Pulo Aura, as it became known, was a triumph for the East India Company and a disaster for the French but it clearly demonstrated that the Royal Navy was overstretched. In October and November 1804 Rainier ordered as many ships as possible to protect the China trade through the Malacca Strait, and to ensure there was no repeat of Pulo Aura.

After his embarrassing defeat, Linois returned somewhat chastened to Ile de France. In Europe, Napoleon was furious: `the conduct of Admiral Linois is miserable,’ he wrote to Decres. `He has made the French flag the laughing stock of the Universe.’ Linois had an uncomfortable interview with the equally unimpressed French Governor- General, Charles Mathieu Isidore Decaen, who urged him to return to sea immediately. Dutifully, Linois continued to prey on British trade for the remainder of 1804, with some success. In September his small squadron attacked naval ships stationed at Vizagapatam, severely damaging the British Centurion and coming away with the East India vessel Princess Charlotte. The operation demonstrated once more the difficulty of protecting a long coastline, but Linois again came under heavy criticism from Decaen for not annihilating the British warship. However, his attacks began to take their toll on Rainier, now ageing and increasingly worn out by the demands of the station, and in 1804 a replacement was sent out to take command. Rainier’s final task was to escort the China trade back to Britain: in September 1805 a convoy with cargo worth £15 million arrived home without loss. This was the most valuable ever to leave Indian waters, and a fitting end to Rainier’s long and under-appreciated career.

His replacement was Rear- Admiral Edward Pellew, who had formerly commanded off Ferrol. Assertive and dynamic, he brought a new vigour to the war in the East. As he sailed out, and in characteristically brisk prose, he dreamed of `giving a blow to the inveterate and restless Enemies of Mankind’. A series of reinforcements from Britain supple- mented the East Indies fleet throughout 1804, and Pellew was able to spread his forces far more widely than Rainier, sending ships to protect the China trade and the Strait of Malacca. Like many others, Pellew struggled to adapt to the oppressive climate, and spent his first weeks bitterly regretting the lengths he had gone to in order to secure the appointment:

We have reached our destination without accident and have felt the glowing heat of a Thermometer at 88º, how I should hold out against such melting I know not . . . I cannot say I am much struck with the Country, and am often very angry with myself for being instrumental to my leaving England and think I did not act wisely.

He was even less impressed with the administrators he found on land: `In short it is a climate of indolence and luxury,’ he wrote, `united with avarice and oppression of which I am truly disgusted.’ He was mercilessly rude about the young men he found lounging around uttering `elegant Quotations from Shakespeare’, and was critical of the East India Company’s control of India, which he likened to Napoleon’s domination of Europe. He had no qualms, however, about halting French imperial ambitions.

From the beginning of his command, Pellew received numerous complaints about the shortcomings in the navy’s protection of commerce. One of the first letters was from Lord Wellesley, bemoaning `the vexatious list of the Captures recently made by the French in these Seas, and carried into the Mauritius in the face of our Cruisers off that island’. This point was immediately hammered home when Linois emerged again in the summer of 1805: on 1 July his small but powerful squadron intercepted and captured the 1,200- ton Indiaman Brunswick off Ceylon. Brunswick had lost many men to naval impressment and was heavily outmatched in terms of guns: threatened with an overwhelming broadside, its captain had little choice but to surrender. On board was the midshipman Thomas Addison, who was devastated to give up the vessel: `I cannot express the intensity of my feelings,’ he later wrote, `being compelled to yield into the hands of the enemy this fine, beautiful and valuable ship.’ Addison and the ship’s officers were held on board Marengo, where they were forced to submit to trying conditions. `They have a poor idea of cleanliness; neatness is out of the question,’ wrote Addison. `Our living was wretched. Only two meals per diem; both put together would hardly make a good English breakfast, with a purser’s pint of sour Bordeaux claret, and a half pint of water.’

After this valuable capture, Linois sailed south hoping to prey on the trade route between the Cape and Madras. In August his fleet encountered a convoy of eleven large ships sailing eastwards, commanded by Rear- Admiral Thomas Troubridge, until recently a Lord of the Admiralty in Whitehall. Linois steered to intercept, only this time he found a real naval escort defending the convoy. The two fleets exchanged distant fire: Addison, still imprisoned in the depths of Marengo, was forced to listen to the sounds of battle. `Firing now commenced with great spirit,’ he recalled, `we heard a thundering return from the English man- of- war, which was soon followed by terrific screams between decks.’ Troubridge did not attempt to chase Linois, for his task was to see the convoy through to India rather than eliminate French cruisers. `We saw no more of the French,’ wrote one of his passengers, Mary Sherwood, `but we afterwards ascertained that we had made Linois suffer so severely that he was glad to get away.’ While Troubridge headed north, Linois proceeded to the Cape, his squadron weakened by successive storms, and then into the South Atlantic where he aimed to raid the coast of West Africa. On 13 March 1806, he met the squadron commanded by John Borlase Warren that had left Britain months earlier in search of Willaumez’s fleet. Forced to fight against a superior foe for the first time – Warren’s flagship was the powerful 90- gun London – Marengo was reduced to a shattered hulk before the French commander finally surrendered. After almost three years of cruising he had captured shipping worth £600,000, a considerable sum that had caused great concern in India and London. However, Linois’s destructive campaign was over and he remained a prisoner until 1814.