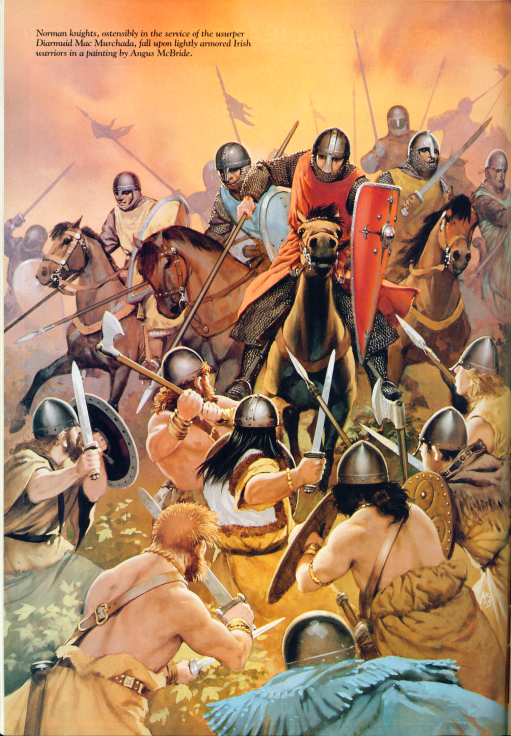

During 1170, meanwhile, Dermot’s resurgence was gathering pace. With the help of Robert Fitz Stephen and his associates, he successfully attacked and captured Wexford (he promptly gave it to Robert, as he had promised to do), reasserted his authority over the leading men of Leinster, and then set his sights on Dublin. It was a violent business. After prevailing in one clash with his opponents, about two hundred severed heads were placed at Dermot’s feet; he identified them all as his enemies, but one in particular caught his attention. ‘He lifted up to his mouth the head of one he particularly loathed,’ Gerald of Wales recorded, ‘and taking it by the ears and hair, gnawed at the nose and cheeks – a cruel and most inhuman act.’ Perhaps so, but Dermot’s performance was enough to bring Rory O’Connor into negotiations. A truce was arranged: Dermot would keep Leinster after acknowledging Rory’s position as high king. Later there would be a marriage between Dermot’s son (whom Rory took as a hostage along with Dermot’s grandson and another kinsman) and Rory’s daughter. Dermot also agreed not to bring any more foreigners to Ireland and to send back those he already had with him. Behind these scenes, however, other plans were being discussed. It was at this point, according to Gerald of Wales who also described the truce, that Dermot began to consider doing more than just recovering what he had lost in 1166. His success on his return had been rapid and impressive. Surely the high kingship was now a realistic aim? Fitz Stephen and Fitz Gerald assured him that it was, but they would need reinforcements. They advised Dermot to get in touch with Strongbow once again.

Dermot’s messengers must have reached Strongbow quickly. Having heard their pleas, he headed straight for the royal court where, according to Gerald, he gave King Henry a choice: either return to him the lands he should have inherited, or allow him to try his luck in Ireland. This time, it seems, the king gave Strongbow some kind of leave to cross the Irish Sea. But even this was not straightforward. Gerald claimed that Henry gave ‘permission of a sort – for it was given ironically rather than in earnest’. And according to William of Newburgh, as Strongbow was about to sail for Ireland, messengers acting on the king’s behalf arrived to stop his departure, threatening him with confiscation of his estates if he set sail. That Strongbow’s lands in Wales and England were taken into the king’s hands seems to be confirmed by entries in the royal financial records relating to his castle at Chepstow (‘Striguil’) and his manor of Weston in Hertfordshire; so even in 1170 Henry seems to have been reluctant to allow Strongbow to go to Ireland. Deaf to any such threats, though, Strongbow sailed for Ireland from Milford Haven, having recruited troops on the way in south Wales, and he landed near Waterford on 23 August 1170 with, Gerald claimed, 200 knights and about 1,000 others (the Song says he brought 1,500 men with him). He was joined on 25 August by Raymond le Gros, who assisted in the capture and garrisoning of Waterford, and by Dermot, accompanied by Fitz Stephen and Fitz Gerald. The alliance between Dermot and Strongbow was sealed by the renewal of the agreement they had first made at their meeting in Bristol: Aife and Strongbow were married, and his position as Dermot’s heir was confirmed. Then, having left a garrison in Waterford, Strongbow set out with Dermot for Dublin where they arrived on 21 September. The city was taken and Asculf, its Norse ruler, was forced to flee. Strongbow remained at Dublin until 1 October, during which time he raided with Dermot into Meath against Tiernan O’Rourke.

News of events in Ireland alarmed Henry II. The success of Strongbow, Fitz Stephen and the rest raised the prospect of Henry’s own men setting themselves up independently of him and out of his reach. William of Newburgh refers to Strongbow, who had enjoyed little fortune previously, as ‘now nearly a king’ and relates how, as a result of his acquisitions in Ireland, he had become celebrated for his wealth and great prosperity in England and Wales. The potential problems for the king were not just confined to Ireland, however. The establishment by an ambitious and ruthless baron of a power base such as Leinster could have ramifications for Henry’s position in Wales and even, in time, in England and beyond. After all, Strongbow had not fared well at Henry hands since 1154: perhaps resentful at what he considered to be the unjust loss of both the lordship of Pembroke and his status as an earl, Strongbow could conceivably use his new lands in Ireland (by the summer of 1171 Strongbow controlled the crucial ports of Dublin and Waterford as well as holding the succession to Leinster) to attempt to foment a revolt in Pembroke or seize it by force. This in turn would send tremors across the Angevin world; it is not an exaggeration to suggest that Strongbow’s successful intervention in Ireland thus had the potential to destabilise the whole of Henry’s dominions.

The king simply could not allow the growth of his barons’ power in Ireland to continue in this unfettered way and, in any event, there was money to be made if Henry could get his hands on thriving ports like Dublin, Waterford and Wexford. His first step was to close the ports to Ireland and order all who had gone there to return before Easter 1171 or face seizure of their estates. Gerald describes Strongbow sending Raymond le Gros to negotiate on his behalf with Henry, and proposing that Strongbow hold his Irish acquisitions from the king. But Raymond was still waiting for a reply from the king when news of the murder of Thomas Becket on 29 December 1170 reached the court. Raymond apparently had to return to Ireland without a favourable response from Henry. But when Dermot MacMurrough died about May 1171, there was a good chance that Strongbow would indeed succeed him. Rory O’Connor and his allies responded by besieging Dublin for two months. Trapped ‘in a most ill-fortified castle, which was enclosed by a flimsy wall of branches and sods’, Gerald of Wales recounted, and with supplies running low, Strongbow, Raymond le Gros and Maurice Fitz Gerald faced defeat. Their desperation, however, combined with news that Robert Fitz Stephen was also being besieged in Carrick Castle by the men of Wexford, led Strongbow to determine on a sudden sortie with three contingents, led by Miles de Cogan, Raymond le Gros and himself, which attacked and routed Rory’s army. Contemporaries estimated that their small force overcame an army of between 30,000 and 60,000 men outside the city walls. These numbers are almost certainly exaggerations (estimates like this in medieval chronicles are notoriously unreliable), but this was a significant moment nonetheless. Rory had managed to bring together a coalition from across Ireland and beyond (ships from Orkney and the Isle of Man were used to blockade Dublin Bay), but it had been scattered by the invaders. From this point, it was probably clear to the Irish that the English planned to stay.

Leaving Dublin under the charge of Miles de Cogan, Strongbow set out to relieve the Wexford garrison. By this time, however, Robert Fitz Stephen had been tricked into surrendering by false news of the defeat of his allies at Dublin, and messengers intercepted the relief force with the news that Wexford had been burnt and Fitz Stephen imprisoned. Strongbow then headed to Waterford, where he was met by Hervey de Montmorency who had just returned from the court of Henry II. Messengers from Strongbow had visited Henry at Argentan in July 1171 and offered to surrender Dublin, Waterford, and the lands that he had acquired through his wife to Henry. But it was clear that any deal would only be concluded if Strongbow himself appeared before the king. So he travelled to meet Henry, who had by now almost completed his preparations for his own expedition to Ireland. At Pembroke, after lengthy argument and mediation by Hervey, Strongbow agreed to surrender the city of Dublin and its adjoining territory, the coastal towns, and all fortified strongholds, and to hold the remainder of the land he had acquired in Ireland as a grant from Henry. With this business concluded, and after visiting the shrine of St David to pray for a smooth crossing and a successful expedition, Henry II crossed the sea to Ireland from Milford Haven and arrived near Waterford on 17 October 1171. Accompanying him, according to Gerald of Wales, were ‘about 500 knights and many mounted and foot archers’; the Song says he brought 400 knights and 4,000 infantrymen, and another source claims Henry came with 400 ships weighed down with warlike men, horses, arms and supplies.

Clearly, whatever the precise numbers, this was a major expedition, and appropriately so. Henry was the first English king (the mythical Arthur apart) to set foot on Irish soil. His first priority was to rein in the activities of his barons in Ireland, but he was also determined to assert his authority over the entire island. Most of the Irish leaders were quick to seek him out, submit, and offer Henry tribute. The men of Wexford appeared before him and handed over a chained Robert Fitz Stephen as a token of their submission. And for men like Dermot of Cork and Donal of Limerick, Henry was a potential ally and protector against the further expansionist ambitions of the English settlers; in any event, they could do little to resist his claims. Even Rory O’Connor, albeit reluctantly, was probably pragmatic enough to accept Henry’s supremacy. As for the English, Strongbow surrendered Waterford and Dublin to the king. Royal officials were installed to administer these cities (Wexford too) and their surrounding areas in the king’s interests, and a great royal palace, made of wickerwork in the Irish fashion, was constructed just outside the city walls. Henry entertained the Irish leaders there at Christmas 1171, even forcing them to change their eating habits: ‘in obedience to the king’s wishes,’ Gerald of Wales records, ‘they began to eat the flesh of the crane, which they had hitherto loathed.’

Within weeks of Henry II’s arrival in Ireland, according to Gerald of Wales, ‘There was almost no one of any repute or influence in the whole island who did not present himself before the king’s majesty or pay him the respect due to an overlord.’ He added that ‘the whole of the island remained quiet under the watchful eye of the king, and enjoyed peace and tranquillity’. It is hard to know how seriously to take this; Henry had certainly asserted his authority, but the balance of power in Ireland remained in a state of tense equilibrium. There was a power vacuum within the Irish leadership and there were divisions within the ranks of the English barons too. Henry had acknowledged Strongbow as the leading English baron in Ireland, but he was keen to keep him in check. So in Meath and at Dublin, Henry installed Hugh de Lacy, the great lord of Weobley in Herefordshire and Ludlow in Shropshire, who had come with him from England. The appointment of a baron as grand as Lacy was no accident. He had the prestige and the resources to stop either Strongbow or any ambitious Irish leader expanding outwards from the lands the king had allowed them to keep.

Henry’s concern with political and military domination extended to the Irish Church too. Ireland lacked centralised political power and the Church was its only national institution. If Henry could stamp his authority on Ireland’s ecclesiastical organisation and structures, he would go a long way towards tightening his hold on Irish affairs more generally. In any event, reform of the Irish Church had suddenly become a more urgent personal priority for the king, and in 1171/2 he saw an opportunity to brush off some of the toxic fallout from the Becket dispute by reinforcing his credentials as a loyal and sincere son of the Church. The chronicler Gervase of Canterbury for one agreed that Henry’s main priority in going to Ireland was to avoid the effect of any papal punishment imposed on him for his part in Becket’s murder.

Henry had papal backing for his plans in Ireland too. Pope Adrian IV may or may not have issued the bull Laudabiliter in 1155. But it is clear that the pope in 1172, Alexander III, enthusiastically supported the reform of the Irish Church. He shared many of the commonly held prejudices about Irish religious practice. When he wrote to Henry II in 1172 about the king’s expedition, he referred to the Irish as people who ‘marry their stepmothers and are not ashamed to have children by them; a man will live with his brother’s wife while his brother is still alive; one man will live in concubinage with two sisters; and many of them, putting away the mother, will marry the daughters’. The pope urged Henry on ‘to subject this people to your lordship to eradicate the filth of such great abomination’. In fact, whilst the Irish Church was far from exemplary in terms of its organisation and practices (Irish marriage customs were notoriously archaic and loose; divorce was easy and intermarriage between close kin was not uncommon), major changes had taken place during the twelfth century. The Cistercians and the Augustinian canons had established numerous religious houses in Ireland by the 1140s, bringing Ireland into contact with international trends, and a proper system of territorial dioceses was being constructed by the 1150s. Under the leadership of the saintly Malachy of Armagh, a close personal friend of Bernard of Clairvaux, who died in 1148, reforming ideas had gradually begun to take hold. So change was happening before the English arrived in Ireland, but Henry II had political, religious and personal reasons for wanting to speed it up when he summoned a council of the Irish Church to meet at Cashel early in 1172. ‘There’, according to Gerald of Wales, ‘the monstrous excesses and vile practices of that land and people were investigated.’ More prosaically, under the supervision of a papal legate, the council dealt with issues such as the proper payment of tithes, marriages and wills. Meanwhile Gerald’s account of the council suggests that Henry was finding it hard to change his controlling ways. The aim of the council ‘was to assimilate the condition of the Irish church to that of the church in England in every way possible’.

How far or for how long the decrees made at Cashel were implemented is not known. The apparent unity of the Irish religious hierarchy in signing up to them would not have made their enforcement any easier. Ireland’s social practices and traditions were ancient and deeply entrenched and it would take more than a few pious pronouncements to change entire lifestyles. And if King Henry himself planned to oversee what happened next, he was soon frustrated. The bad weather during the winter of 1171–2, which interrupted food supplies to his army, was accompanied by dysentery within the ranks. The king then learned that papal envoys had arrived in Normandy; they were threatening to impose an interdict on Henry’s lands if he did not come to meet them and settle his dispute with the Church. So, almost certainly earlier than he had intended, Henry left Ireland in April 1172. In the following month he finally brought the Becket dispute to a formal end by making his peace with the papal legates at Avranches. There was no doubt, in Gerald’s mind at least, that Henry left Ireland with his ambitions unfulfilled. He was ‘particularly grieved at having to take such untimely leave of his Irish dominion, which he had intended to fortify with castles, settle in peace and stability, and altogether to mould to his own design in the coming summer’. If this had indeed been Henry’s plan, Strongbow, his collaborators and his competitors must have been relieved that the king was no longer breathing down their necks. There was some comfort for the king, though, as he soon began to reap the reward for settling his dispute with the Church. In September 1172, after hearing reports of the council of Cashel, Pope Alexander III wrote three letters, one to the Irish bishops, a second to the Irish kings and leaders, and a third, which has already been mentioned, to Henry II himself. The three letters together urged the Irish to accept Henry as their ‘king and lord’, because Henry had gone to Ireland as a religious reformer, to rescue the Irish from the state of religious barbarism into which they had fallen. However genuine his religious motives really were, by the end of 1172, Henry had rebuilt his relations with Rome and reinforced his authority over the Irish religious and political hierarchies at the same time. His stay in Ireland had lasted barely six months, and he never went there again. But by establishing the principle of English sovereignty over Ireland, a principle endorsed by papal blessing, his stay had been highly significant nonetheless.

Following the outbreak of the Great Revolt against Henry in April 1173, the king summoned Strongbow and some of his baronial colleagues in Ireland to fight in Normandy. The earl defended the crucial frontier fortress of Gisors for the king and was present at the siege of Verneuil in August. The king was grateful and Strongbow returned to Ireland in the autumn of 1173, Henry having made him the guardian of all Ireland, including Dublin and Waterford, on his behalf, with Raymond le Gros as his deputy. The king also granted Strongbow the town of Wexford and Wicklow Castle. However, the absence of Strongbow and the other settler barons in Normandy had encouraged a revolt in Leinster; the Irish, after all, according to Gerald, are ‘a race of which the only stable and reliable trait is their being unstable and un–reliable’. In south Wales too the Welsh had taken advantage with a great raid on Netherwent on 16 August, which reached as far as the very walls of Strongbow’s castle at Chepstow. In 1174 he tried to reassert his authority in Ireland when he led an expedition into Munster against King Donal O’Brien of Limerick. But, assisted by Rory O’Connor, Donal inflicted a heavy defeat on the earl and forced him to retreat to Waterford. There were also tensions within Strongbow’s own ranks. According to the Song, Raymond le Gros had by this time left Ireland and returned to Wales. Having asked Strongbow for the hand of the earl’s sister, Basilia, in marriage and for the vacant constableship of Leinster, he had been refused and had departed ‘full of resentment’. Raymond was now recalled by Strongbow, a sure sign of the difficulties he was facing. There was a price to pay for Raymond’s renewed support, though, and Raymond was finally offered marriage to Basilia, together with land grants in Fotharta, and Uí Dróna and the coastal site of Glascarrig. Gerald depicts Strongbow as hemmed in and inactive in Waterford and only the timely arrival of Raymond with fifteen ships (or three, according to the Song), thirty knights, 100 mounted archers and 300 foot archers prevented Wexford from falling into Irish hands. Raymond celebrated in fine style with his wedding where ‘a whole day had been spent in feasting and a night in enjoying the delights of the bridal bed’. Almost immediately, however, Rory O’Connor raided into Meath, which was under the stern rule of Hugh de Lacy, destroying the castles of Trim and Duleek, and threatening to head further north. Strongbow and Raymond were quick to respond (the latter ‘not in the least slowed down by the effects of either wine or love’, Gerald says), forcing Rory to withdraw.

Such events demonstrated that the English grip on Ireland was far from secure by 1174. The Irish themselves, not least Rory O’Connor, remained determined to resist the further spread of English influence and, where possible, to destroy it. The continuing vulnerability of the settlers’ position in Ireland, and of Henry II’s own newly established power there, probably lay behind the so-called Treaty of Windsor, an agreement the king made with Rory O’Connor in October 1175. Under the terms of this deal, Rory was to rule Connacht as Henry’s ‘liege man’. In other words, whilst Rory owed personal service and tribute to the king, he did not hold Connacht from him as a feudal vassal, but ‘as fully and as peacefully as he did before the lord king entered Ireland’.

Henry recognised Rory’s high-kingship over those parts of Ireland not explicitly reserved to English control. In practice, this meant that Rory was left to do what he could to assert himself in the north and south-west, whilst English control over Dublin, Leinster, Meath and Munster from Waterford to Dungarvan was pragmatically acknowledged. What Strongbow and the other settler barons made of all this is unknown (the treaty certainly didn’t put any stop to their further advances in the following years), but the earl was with the king at Marlborough and witnessed a number of his charters at about the time the treaty was negotiated. Meanwhile in Ireland, Raymond le Gros was leading an Anglo-Norman force to capture Limerick, a command which, according to the Song, had been handed to him by Strongbow. Hervey de Montmorency complained to the king that Raymond was acting against the king’s interests and aspired to seize control, not only of Limerick, but of the whole of Ireland. Henry responded by sending four messengers to Ireland early in 1176, two of whom were to escort Raymond to him, while the other two were to remain with Strongbow. As Raymond was about to depart with the royal envoys, news came that Donal O’Brien had besieged the Anglo-Norman garrison of Limerick. Strongbow, according to Gerald, prepared to go to the assistance of the garrison, but his men asserted they would only fight under the leadership of Raymond. Strongbow agreed with the envoys that Raymond should return to Limerick. The Anglo-Norman garrison was relieved on 6 April, but news then broke of Strongbow’s death.

He probably died in Dublin, but the precise date of his death is unclear. Gerald of Wales says it was about 1 June 1176, but other sources put it as early as April. Strongbow was buried at the church of Holy Trinity, Dublin, where he was commemorated every 20 April. The cause of Strongbow’s death is rather obscure too. Gerald says that the earl had been taken seriously ill some time, perhaps several weeks, before his death. Other sources vary in their graphic details: according to one, an ulcerated foot killed him, whilst another described him dying ‘an unholy death . . . after a long wasting sickness’. Both agree that his demise was the revenge of the saints whose churches he had plundered. Strongbow had not been blind to the needs of his soul, however. He founded a nunnery at Usk and made grants in favour of numerous religious houses in England, Wales and Normandy. In Ireland he made grants to Holy Trinity, Dublin, and St Mary’s Abbey, Dublin, and to the Knights Hospitaller.

It is arguable that Strongbow died at the right time. The signs are that, by 1176, his grip on power in Ireland was starting to loosen. A man like Hugh de Lacy was able to consolidate his position by constructing castles such as the one at Trim, which nailed down his control of Meath, and by installing his tenants from England, and to do so with royal backing for his attempt to build up his lordship. By the time he died in 1186, an Irish chronicler felt it appropriate to describe Lacy as ‘king of Meath and Breifne, and Oriel’ (in other words, mid-western Ireland), and to note that the neighbouring kingdom of Connacht paid him tribute. ‘He it was that won all Éirinn [Ireland] for the foreigners,’ the chronicler proclaimed. Strongbow could not match this kind of power and influence. And even within his immediate family there are signs of tension by the end. When Strongbow’s sister Basilia sent news of her brother’s death to her husband Raymond le Gros, her coded reference to Strongbow is not hard to decipher: ‘that large molar tooth which caused me so much pain has now fallen out,’ she declared. Had Strongbow lived longer, it is hard to see how his relationship with Raymond could have prospered. Strongbow was a remarkable man, but his support in Ireland had never been deep or particularly influential. After Henry II’s intervention in 1171, and despite his appointment by the king as governor in 1173, Strongbow had struggled to recover his earlier dominant position among the English elite. He was ultimately unable to establish members of his own family in important positions for any length of time, and those men who can be identified as his followers (the witnesses to his charters or the recipients of his land) were not generally men of substance. He left only infant heirs (his only son, Gilbert, was a minor in 1176), and so Leinster came into royal custody when he died. Strongbow’s legacy did survive, though. Gilbert died in his teens, but Strongbow’s daughter Isabel married William Marshal in 1189. Through his wife, William succeeded to the lordships of Chepstow and Leinster, and in 1199 he regained the earldom of Pembroke.

In 1177, meanwhile, Henry II made another attempt to organise Ireland’s political landscape. Perhaps in response to complaints from those English settlers who felt that the Treaty of Windsor had been too generous to Rory O’Connor, at the Council of Oxford in May of that year Henry announced that he would keep the cities of Cork and Limerick for himself. The kingdom of Cork, meanwhile, was carved up between some of the leading settlers, whilst the kingdom of Desmond was given to Robert Fitz Stephen and Miles de Cogan and the kingdom of Limerick to Philip de Briouze. Most important for the future, however, was Henry’s decision to make his youngest son, John, king of Ireland. To confirm this he asked the pope to provide John with a crown. John was not yet ten years old, and his appointment was the cornerstone of a long-term plan to bring Ireland securely into the Angevin territorial fold. John did not travel to Ireland until 1185, but his entrance onto the stage of Irish affairs began a new act in the drama.