GENERAL BACKGROUND

Fidel Castro’s desire to take the offensive against capitalism and spread revolution ultimately led to the Cuban army fighting in Africa. His aim was to create many Vietnams, reasoning that U.S. troops bogged down throughout the world could not fight any single insurgency effectively. Africa was still emerging from colonialism when Castro came to power, thus presenting him many opportunities.

The Cuban presence in Africa evolved through many phases before leading to the introduction of combat troops. The first phase, guerrilla training, began in 1960 when arms and medical personnel were sent to the Algerian National Liberation Army (Armée de Libération Nationale). This was followed by the first permanent military mission which arrived in Ghana the following year when a few instructors set up a training camp near the border with Upper Volta. Guerrilla training expanded and continued until the early 1990s.

In the second phase, Cuba attempted to militarily bolster a friendly nation. In October 1963 Cuba supplied Algeria with forty Russian-built T-34 tanks and some fifty Cuban technicians who were at sea on board the Aracelio Iglesias when a border conflict erupted between Algeria and Morocco. This equipment was followed within the same month by perhaps three other shipments (two by sea, one by air), raising Cuban strength to approximately 300 men, plus artillery, mortars, and tanks. Apparently the Cubans did not participate in combat and they were withdrawn by the end of the year after training Algerians in the use of the hardware.

During the third phase, Cuba attempted to influence the outcome of tribal rivalries, siding with groups whose ideologies were most compatible with that of Cuba. This phase opened with high-level delegation visits to Africa. In October 1964, Cuban President Osvaldo Dorticos went to the Second Conference of Non-Aligned Nations, meeting in Cairo, and declared that Cuba could not be passive “toward mankind’s greatest problems.”

In December, Che Guevara traveled to Algeria, Mali, Congo-Leopoldville (soon to become Zaire), Ghana, Guinea, Dahomey, Tanzania, and Egypt. Che was empowered by Castro to offer material aid to those who shared Castro’s ideology. By mid-1965 the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) received weapons from Cuba. Arms for the Guinea rebels, the African Party for the Liberation of Portuguese Guinea and the Cape Verde Islands, arrived in 1966. And apparently, Cuban instructors were training members of the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique in Tanzania by the late 1960s.

Che returned to Africa to lead guerrilla fighters in Zaire, which he entered through Tanzania with a small band of Cubans in the spring of 1965. They were joined by several hundred more Cubans who entered through Congo-Brazzaville. However, Che found the rebels unwilling to fight; and after Joseph Mobutu seized power in November 1965, most of the Cuban fighters withdrew. Che remained behind in neighboring Congo-Brazzaville until March 1966 organizing the Cuban mission that had been sent there.

Adding to the Zaire setback, two of Castro’s closest allies were toppled by military coups—Ahmed Ben Bella in Algeria (1965) and Dr. Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana (1966). Thus, Cuba lost both of its African training bases. Following these experiences Cuba paid more attention to protecting its hosts. New training bases were established in Congo-Brazzaville and former French Guinea. In Brazzaville, Cubans formed part of the presidential guard, and they also trained a militia from the ruling party as a counterbalance to the national army. The Cuban mission to Congo-Brazzaville grew to nearly one-half the size of the entire Congolese army. On June 27, 1966, that army attempted to overthrow President Massamba Debat. Cuban troops and the party militia protected the political leaders for three days. Capt. (later Brig. Gen.) Rolando Kindelán Bles stated, “We Cubans opposed the coup. We took the entrance to the airport, the main radio station; we controlled the road intersections; the nerve centers; and in that way we were able to impede it.” The coup collapsed when the Congolese army refused to fight the Cubans. In August 1968 Marien Ngouabi did overthrow the Cuban-supported government. Notwithstanding, Ngouabi permitted the Cubans to continue to operate in the Congo.

Cuba continued to send military help to leftist regimes in African nations, and additionally focused upon liberating Portuguese colonies, thus beginning phase four.11 Cuban aid to former French Guinea (independent since 1958) was directed in part to the guerrillas fighting the Portuguese in bordering Portuguese Guinea (today Guinea-Bissau). Cuban advisors began operating with the guerrillas in February 1967, and in November 1969 the Portuguese captured Cuban Capt. Pedro Rodriguez Peralta.

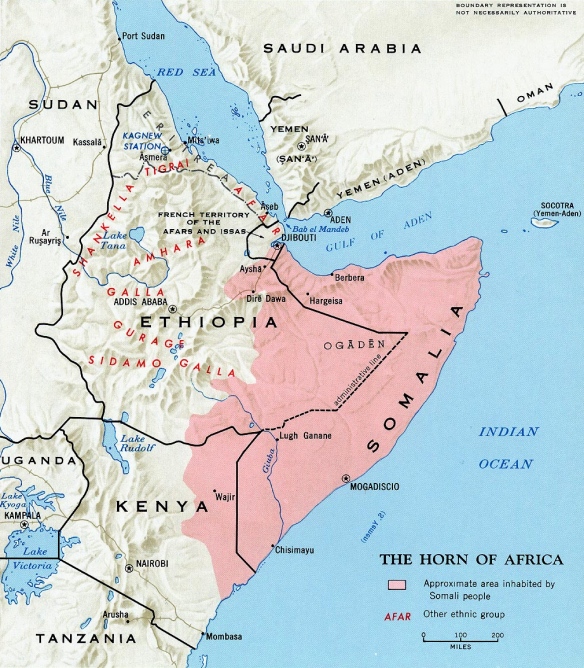

Between the late 1960s and the early 1970s, Cuban activity in Africa subsided. However, it soon increased again with missions being sent to ex-Spanish Equatorial Guinea, Somalia, Algeria, Mozambique, and Sierra Leone—plus to the Middle East, South Yemen, Syria, and Iraq.

ANGOLA BACKGROUND

Angola was strategically important because of the petroleum exports from the Cabinda enclave and because the Benguela Railroad, the major transportation link for landlocked Zaire and Zambia, ran through it.

The war for the liberation of Portuguese West Africa (the future Angola) from colonial rule began in February 1961 when the Marxist-oriented Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) attacked the colonial headquarters in the capital of Luanda. The Portuguese had occupied some coastal regions since the end of the fifteenth century, although modern Angola became Portuguese only after the Conference and Treaty of Berlin in 1885.

Between 1961 and 1975 an estimated 20,000 Africans died in the fighting, and by the late 1960s perhaps half of the Portuguese national budget was spent on the war in Angola. By the mid-1970s, Angola was the last Portuguese colony in Africa. On April 25, 1974, junior Portuguese officers overthrew Dr. Marcelo Gaetano, who had succeeded the long-serving dictator Antonio de Oliveira Salazar. The new, leftist Portuguese government invited the principal Angolan guerrilla organizations to participate in the transition from colonial rule to independence. As a consequence, fighting broke out among the competing guerrilla factions in March 1975 to see who would win control of the country from the Portuguese.

OPPOSING FORCES IN ANGOLA

Five “armies” were fighting for control of Angola—three from disparate revolutionary factions plus those of Portugal and the Union of South Africa. In addition, the Zairean army operated openly in the northern region of Angola.

The National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA), which fielded about 5,000 fighters, dominated the northwestern section of Angola. Led by Holden Roberto, the Bakongos tribe provided its popular base. It was considered pro-West and was supported by Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire. The Zairean army even operated within the area controlled by Roberto. Despite his pro-West affiliations, Roberto secured help from Peking in December 1973. Between June and August 1974, China sent 450 tons of military material to the FNLA via Zaire and began training its soldiers.

Just below that area was the region dominated by the Popular Movement of Liberation of Angola (MPLA) led by Agostinho Neto. The MPLA had about 2,000 fighters and its support base was among the Mbundu Tribe. During the mid-1960s, fighters from the MPLA trained in Cuba and a Cuban-operated base in the Congo.

The MPLA received most of its arms from the Soviet Union; these weapons were shipped through the People’s Republic of the Congo-Brazzaville. During one week in October 1975, the MPLA received twelve MiG aircraft, twenty-one tanks, thirty armored cars, 200 rocket launchers, plus small arms. By the spring of 1975, Neto appreciated that his MPLA guerrillas could not effectively use the advanced Soviet weapons being provided; hence he turned to Castro for advanced training, which began in June 1975, one month after the request. This significantly changed the balance of power among the rival Angolan factions. Because of Cuban and Soviet help, the MPLA grew in military prowess and, as a consequence, attracted many new recruits.

South of the territory dominated by the MPLA lay the area controlled by the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), led by Jonas Savimbi. The Benguela Railroad passed through this area. The movement had splintered from the FNLA in 1966 over tribal differences and objections to clandestine support from the United States. The UNITA fielded 1,000 men and its tribal support came from the Ovimbundu in the south.

The Portuguese government had about 55,000 troops in Angola but by mid-1974 was committed to withdrawing. To the south was the well-equipped, well-trained 50,000-man South African army.

OPENING STRATEGIES IN ANGOLA

The Cuban-supported MPLA wanted to seize control of most of Angola’s provincial capitals prior to November 11, 1975, the date set by the Portuguese for Angolan independence. In response, the FNLA and the UNITA sought aid from the Union of South Africa. South Africa, for its part, wanted to prevent the MPLA from winning control of Angola.

ANGOLA-CUBAN TROOPS IN COMBAT

Between July 12 and 15, 1975, the MPLA successfully captured Angola’s capital, Luanda, but was immediately threatened from both the north and the south. In the north, FNLA troops attacked the MPLA but were stopped at Kinfangondo (12 mi N of Luanda). In the south, South African troops crossed the border between Angola and Namibia on August 11 and seized the hydroelectric dams on the Cunene River which spanned the border. Within a few weeks, other South African troops captured the towns of Pereira d’Eça and Roçadas, thus blocking the route leading to the dams from the north. The South African forces advanced northward.

Cuba reacted quickly to the dangers confronting the FNLA. Castro called for volunteers from the Cuban army to fight in Angola. Many who volunteered were black, possibly an attempt to demonstrate a racial bond with Angola. In early September the Cuban merchantships Viet Nam Heroico, Isla Coral, and La Plata, packed with troops, vehicles, and 1,000 tons of gasoline, sailed 5,000 miles to the African nation. Even though Angola was a petroleum-producing nation, Castro wanted to reduce the possibility that his supply could be interrupted, so the Viet Nam Heroico carried 200 tons of gasoline in 55-gallon drums in the holds, which were left open for ventilation, and La Plata carried the drums strapped to the deck.

The United States held a secret, high-level talk with Cuba to express its consternation over Cuba’s actions, but this had little effect. The Cuban troops landed in early October.

The South African force driving northward from the Namibian border posed the most significant threat to the MPLA, so some of the recently arrived Cuban troops joined the MPLA troops moving against Nova Lisboa (today’s Huambo, 300 mi SE of Luanda) and Lobito (220 mi S of Luanda). The remainder established training camps at Benguela, Saurimo, Cabinda, and Delatando.

On October 6 Cuba and the MPLA clashed with the FNLA and South African troops at Norton de Matos and were badly beaten. While the Cubans had been crossing the Atlantic, the South Africans had apparently airlifted a few troops plus some armored cars into central Angola. These were supplied by C-130 aircraft flying into Nova Lisboa and Silva Porto (275 mi SE of Luanda).

On October 23 the South Africans launched a major offensive. A mechanized column composed of armored cars, motorized infantry, and artillery manned by the South African army, Portuguese mercenaries, and FNLA fighters (loyal to Daniel Chipenda who had defected from the MPLA) attacked. On that day the column captured Sá da Bandeira (400 mi S of Luanda) and on the twenty-seventh the port of Moçãmedes (380 mi S of Luanda), without resistance. The column then fell back to Sá da Bandeira but then turned north against Benguela (250 mi S of Luanda) where the Cubans had one of their training camps.

The mechanized column detoured to Nova Lisboa on November 1. It then resumed toward Benguela. The Cubans blocked the column on November 4 with 122mm rocket fire, causing the South Africans to request heavy artillery which could outdistance the rockets. The next day, the Cubans abandoned Benguela and Lobito, and by November 11 (Independence Day) the South African column was advancing on Novo Redondo (120 mi S of Luanda).

Castro reacted to the presence of the South African armored column by announcing “Operation Carlotta,” a massive resupply of Angola, on November 5. On the seventh Cuba began a thirteen-day airlift of a 650-man special forces battalion. The Cubans used old Bristol Britannia turboprop aircraft, making refueling stops in Barbados, Guinea-Bissau, and the Congo before landing in Luanda. The troops traveled as “tourists,” carrying machine guns in briefcases. They packed 75mm cannons, 82mm mortars, and small arms into the aircrafts’ cargo holds. Aircraft with normal take-off weights of 185,000 pounds were lifting off weighing 194,000 pounds. Pilots were flying over 200 hours per month. A round trip required 50 hours.

Castro’s resupply efforts by sea were no less dramatic. Perhaps five troop-laden ships had sailed from Cuba in late October, arriving in Angola during the middle of November. Cuba’s only two passenger ships were fitted with cots, field kitchens, and additional latrines. Paper plates were used and plastic yogurt containers served as glasses. The ballast tanks were used for bathing and toilet water. Ships normally outfitted for 306 persons (passengers and crew) sailed with 1,000 on board in addition to armored cars, weapons, and munitions.

BATTLE OF BRIDGE 14

Between December 9 and 12, Cuban and South African troops fought between Santa Comba (180 mi SE of Luanda) and Quibala (150 mi SE of Luanda); the Cubans were defeated. Among the Cuban casualties was the commander, Raúl Argüello, a veteran of the Cuban Revolution. He was killed when his vehicle hit a land mine. At the same time UNITA troops and another South African mechanized unit captured Luso (500 mi ESE of Luanda).

Following these defeats, the number of Cuban troops airlifted to Angola more than doubled, from about 400 per week to perhaps a thousand. Among these troops were seasoned veterans of the Cuban Revolution and wars in Latin America, such as Victor Chueng Colas, Leopoldo Cintras Frías, Abelardo Colome Ibarra, and Raúl Menendez Tomassevich. By the end of January 1976, some 7,000 Cuban troops were in Angola. Cuba also prepared to send at least one artillery regiment and a motorized infantry battalion.

And, Cuba no longer was having to go it alone in aiding the MPLA. On November 13, 1975, Soviet military advisors had arrived in Angola. In early 1976 the Soviets began providing IL-62 jet transports to the Cubans, significantly increasing their airlift potential. These aircraft introduced fresh troops and rotated veterans into the mid-1980s.

MPLA’S NORTHERN OFFENSIVE

On January 4, 1976, the Cuban-supported MPLA captured Uije (150 mi N of Luanda) and the major airbase 25 miles to the east the following day from the FNLA. On the twelfth, the MPLA took the port of Ambriz (125 Mi N of Luanda). As a consequence, the troops from Zaire, who had supported the FNLA, pulled back across their border.

In mid-January, the South Africans withdrew from Cela and Santa Comba deep in Angola to a position just north of the Angolan-Namibian border. This was probably influenced by a number of factors. First, the surge in Cuban troops required South Africa to make a decision to either increase its army in Angola or withdraw. Second, the United States stopped supplying Angolans opposed to the MPLA. And third, the Cubans temporarily stopped airlifting troops to Angola, which provided a graceful way out for its opponents.

Cuba resumed airlifting troops to Angola in late February 1976 at a reduced rate. In that month, the MPLA captured the last UNITA stronghold and drove its rivals into neighboring countries. The MPLA also had to battle a new faction, the Front for the Liberation of the Cabinda Enclave (FLEC), led by Francisco Xavier Lubtoa.

By March 1977 the MPLA controlled enough of the country to permit Castro to pay a state visit. However, in May Nito Alves and José Van Dunem attempted an unsuccessful coup against Agostinho Neto. Cuban troops helped defeat the rebels. In July, an additional 4,000 Cuban troops were introduced into Angola. In spite of this, the UNITA was able to regroup and launch an offensive against the MPLA in December. The Cuban-supported MPLA was able to counterattack beginning in April 1978.

In September 1979 Neto died while undergoing surgery in the Soviet Union. José Eduardo dos Santos succeeded him. Throughout the late 1970s, the MPLA aggressively eliminated potential dissenters.

The fighting dragged on for years while Fidel directed operations from Havana. Brig. Gen. Juan Escalona, Chief of the Command Post, stated:

For over two years every day, without fail, between 2:30 and 3:00 in the afternoon I was advised I had a visitor. I knew the Commander in Chief had arrived. He would stay in the Armed Forces Ministry until the early hours of dawn. The entire Angolan operation was directed by Fidel minute by minute.

South African forces frequently crossed into Angola to destroy South-West African People’s Organization (SWAPO) training bases. More critically, the MPLA could not root out the UNITA (which had emerged as its principal opposition) and became, therefore, increasingly dependent upon Cuban combat troops. By 1987 some 24,500 Cuban troops held defensive positions in Angola. The MPLA controlled the larger population centers while the UNITA held the countryside.