At the end of 1508, Julius II (1503–13) masterminded the League of Cambrai which pledged most European nations (not including England) to join with a group of Italian states in assisting his holiness to oust Venice from mainland territories it had acquired over the years. The warrior-pope boasted that he would reduce proud Venice to the status of a fishing village for its presumption in encroaching on papal territory and its assertion of a measure of spiritual independence from the Holy See. France played the major role in the ensuing war, which saw Venice swiftly and comprehensively defeated and stripped of most of its territory. Now Julius had a bigger problem on his hands than a recalcitrant Italian republic; the French had come and were in no hurry to depart. Moreover, Louis XII had further provoked papal wrath by summoning an ecumenical council to consider church reform and to dethrone the corrupt pope, widely known to be a self-indulgent, irascible pederast. With his political and spiritual authority both being threatened, Julius had to take serious action. He denounced the ‘barbarians’ and formed a new alliance – including the recently humiliated ‘fishing village’ – to drive them back over the Alps. The Spaniards and the Swiss were the most active components of the pope’s ‘Holy League’ but, at the end of 1511, it was also joined by Henry VIII.

From the beginning of the reign his representatives had been active in Rome. Good Catholic that he was, Henry determined to have effective influence in the headquarters of the church. As early as September 1509 he despatched Christopher Bainbridge, Archbishop of York, to the Vatican as his resident ambassador. Bainbridge was the last and the most successful ecclesiastic of the old order. His position as chaplain to Henry VII had been the launch pad for his meteoric rise through the episcopal ranks and he held several lucrative appointments. He easily ingratiated himself with Julius, who made him a cardinal within eighteen months of his arrival (he was the only English churchman to become a resident member of the Curia, the governing body of the Catholic church) and favoured him with his confidence. Bainbridge was an excellent choice from Henry’s point of view because he was a skilled politique, able to obtain impressive proof of the pope’s support for his young master and also to further the intrigues of the anti-French party. Bainbridge, unlike several of his conciliar colleagues back in Westminster, was a zealous francophobe. His success was very gratifying to the king. Bainbridge obtained from Julius a special indulgence for all who participated in military action against France. The pope, as well as sending to England generous gifts of wine, cheese and the much-coveted Golden Rose, promised to bestow upon Henry the title ‘Most Christian King’, which had just been stripped from Louis XII. Moreover, he declared that he would travel to Paris and personally place the French crown on Henry’s head – after Henry had defeated Louis in battle. The quid pro quo demanded of the English king was that he would mount a campaign which would deflect Louis from his military activities in Italy. Plans for military action were already well in hand with Ferdinand of Spain who had his own reasons for courting Henry’s aid and was bringing pressure to bear via his daughter as well as through the usual diplomatic channels.

Everything seemed to be falling into place to support Henry’s own belligerent inclination: he was being flatteringly courted by the head of the church and by one of Europe’s most powerful princes: he had the prospect of gloriously inaugurating his reign by reuniting the crowns of England and France; and he could claim to be marching his armies on to foreign soil in the interests of Christendom. In international relations, Ferdinand, no less than Louis XII, used the need for widespread church reform as a plank of his diplomacy. Italy had become a major cockpit in the long-running conflict between France and Spain and both monarchs found it necessary, at times, to woo the pope. However, when it suited either of them to pursue peace the message went out for all the leaders of Christendom to join in a league for the purpose of summoning a council which would carry out those sweeping moral and doctrinal reforms that the scandalously worldly Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia) and the warrior-pope Julius II were neither willing nor able to undertake. On this issue Henry found himself in something of a dilemma. He was, and wished to be recognized as, a loyal son of the Holy Father but he was also determined not to be left out of any summit conference. He let it be known that he was in favour of an ecumenical council but only if it was convened and headed by the pope. Henry’s Arthurian destiny could scarcely be beckoning more clearly. While his captains made their military preparations, his diplomats distanced themselves from their French counterparts. He declined an invitation by Louis to send delegates to his council in Pisa and, when Julius trumped Louis’ ace by calling his own council (the Fifth Lateran) to meet in Rome, Henry sent as his representative, Silvestro de’ Gigli, Bishop of Worcester (a name destined to reappear in one of the more unsavoury diplomatic intrigues). All the parties to these labyrinthine negotiations were so blinkered by pursuing their own ends that they could not see the signs of the coming crisis which would overwhelm them. Thus, for example, the Lateran Council, having, apparently, achieved its object of bolstering papal authority, was wound up in March 1517. Seven-and-a-half months later Martin Luther issued his Ninety-Five Theses, and changed forever Europe, the church and the world.

Such eventualities were well beyond the horizon as Henry prepared for war. Between, on the one hand, the glorious spectacle of multicoloured heraldry, nodding helms, prancing steeds, glinting armour and ranks of soldiers marching to the sound of pipe and drum and, on the other, the realities of victorious combat there is, of course, a great gulf fixed. Troops have to be mustered, transported, equipped, fed and paid. Strategies have to be developed. Tactics have to be planned and constantly adapted to give effect to those strategies. The king had no talent for, or interest in, the fundamentals of military logistics. Nor, it seems, was he capable of planning and preparing for the long haul. Government propaganda projected the grandiose vision of Henry regaining the ancient territories of the crown – Anjou, Maine, Gascony, Guyenne and Normandy – but there is no evidence that the king understood just how difficult it would be to realize such an objective, nor that he calculated whether he had at his disposal the resources necessary for it. Henry and his hawkish coterie psyched themselves up with gung-ho rhetoric. They were neither the first nor the last to believe that waging war for ‘king and country’ was a self-justifying occupation which would be divinely blessed with success.

Careful observation of and reflection on what was happening on foreign battlefields would have led to a more effective preparation for Henry’s campaigns. Warfare was developing rapidly in this period. Handguns were challenging bows and arrows. Field artillery was coming into its own. The balance of cavalry and infantry was changing. The emergence of professional mercenary armies (notably those of Switzerland) armed with the long pike was beginning to dominate battlefield tactics. However, it was not until later in the reign that English armies began to take on a new shape. The forces that crossed the Channel between 1511 and 1513 still relied on the longbow and the cavalry charge. An important development that was inaugurated early in the reign was the tentative beginning of a permanent navy, but even this was more a matter of royal prestige than of being at the cutting edge of technology.

When Henry learned that James IV of Scotland had taken delivery from a French dockyard of the Michael, the biggest warship afloat, he immediately ordered a vessel that would outclass it, the Henry Imperial or Henry Grace à Dieu, launched in 1513. Soon afterwards, being impressed by the effectiveness of oared vessels, he commissioned the 800-ton Great Galley, an impressive three-masted warship which had a gun deck above the rowing deck. He was inordinately proud of this ship but its effectiveness is doubtful. There is something stirring about the sight of a great man-of-war and there is no reason to doubt that, even in the days before steam power, people’s hearts were moved by the spectacle of a stately great ship under full sail. The showman in Henry certainly responded to these magnificent fighting machines. At the launching of the Great Galley in 1515, he strutted the deck dressed as a sailor – but in cloth of gold! Immediately on coming to the throne he began to augment the royal navy and, by the time of the French campaign of 1513, he had, by building, purchase and capture, more than doubled the fleet inherited from his father. This, of course, was a necessary concomitant of his intention of invading France. To convey troops across the Channel and to keep it clear of enemy shipping he had to have naval supremacy, but his programme was only a beginning. It contributed nothing to the development of naval warfare or to place England in a position to challenge the supremacy of Spain and Portugal in transoceanic endeavour.

This reincarnated Henry V, then, demanded war. Through his diplomats he prepared for war. He equipped himself with the materiel of war. In the tiltyard with his friends he played at war. However, someone else had to shoulder the massive burden of actually organizing war. Into that office the king’s almoner slipped adroitly.

Like his royal master, Wolsey was a theatrical extrovert, but he was never an uncontrolled one. Perhaps this explains the hold he came to exercise over the young Henry. Wolsey was always careful never to appear in competition with the king. His splendour was a complementary splendour, designed to enhance Henry’s reputation. The royal almoner appealed to Henry because his personality straddled court and council. He was a fun-loving bon viveur but also a serious man of affairs, capable of giving sound advice. Like the king, he intended England to be a major player in the affairs of Christendom and that meant presenting an impressive front to the world. He provided the young monarch with a magnificent object lesson in how a splendid Renaissance prince should live. God was robed in splendour and it behoved his representatives in church and state to reflect something of his effulgence. Henry paid frequent visits to Wolsey’s palaces at York Place and Hampton Court, and Wolsey was always ready with lavish entertainment – even, apparently, when the royal party was unannounced. His biographer tells the story of one such occasion. The churchman and his guests were in the middle of a banquet when a group of ‘foreign shepherds’ arrived. These rustics had never spent a night on the hillside looking after flocks and they were all dressed in vivid silks. When they had been invited to join in the eating, drinking, dancing and gambling and when the fun was at its height, the host suggested that perhaps there was among the strange guests one who outranked him and who should take the seat of honour. Indeed there was, came the reply, but could Wolsey penetrate the great man’s cunning disguise? This was, of course the signal for Wolsey to humbly unmask the king, which he proceeded to do. Unfortunately, he got it wrong and pointed to Sir Edward Neville, who was much like Henry. Laughter all round!

Wolsey thus entered enthusiastically into setting a tone of conspicuous consumption, a tone eagerly taken up by courtiers, nobles and gentlemen who could afford to do so (or who borrowed heavily to maintain their place among the social elite). The example set by Henry and Wolsey encouraged a spate of competitive domestic construction and created a demand for land and convertible buildings that (without knowing it) was hungrily waiting for the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s. Every commodious country mansion and every town house enhanced by the artistry of foreign craftsmen demonstrated to England’s continental neighbours that the Tudor elite were not boorish backwoodsmen but shared with Frenchmen, Burgundians and Italians an appreciation of all the latest fashions. Wolsey’s exuberant lifestyle matched that of Henry and was based on the same philosophy. For this reason and because Henry enjoyed Wolsey’s company and respected the intellect of this man who took uncongenial burdens from his shoulders, Henry trusted Wolsey more and more. Wolsey became, by degrees, the king’s right-hand man, his chief adviser, the intermediary between the itinerant court and the council at Westminster. He took on himself the arrangements for equipping and victualling the royal forces employed in the 1512 campaign but the strategy was that of the king.

The results of its implementation were humiliatingly disastrous. The plan was for an Anglo-Spanish invasion of Guyenne, in south-west France. Ferdinand would supply his son-in-law with cavalry, cannon and wagons and help him to claw back part of the territory of Aquitaine, which had once been annexed to the English crown. The Spanish king, however, had different priorities. He intended to use the English attack as a diversion while he overran Navarre, immediately to the south. This ancient kingdom, bordering Aragon, Castile and France, controlled the principal Pyrenean pass used by pilgrims, merchants and armies and its independence was, therefore, an irritant which Ferdinand was determined to remove. Ignorant of his ally’s duplicity, Henry embarked on the great enterprise with typical bravura. High offices were distributed to his close companions. Thomas Grey, Marquis of Dorset, was appointed commander of the land operation and Edward Howard was made admiral of the fleet, charged with keeping the Channel approaches clear of French warships. Other privy chamber members, including, Charles Brandon, Henry Guildford and Thomas Knyvet, clamoured for positions of honour and were rewarded with commissions. The assembly of the force in Southampton was an impressively theatrical event:

To see the lords and gentlemen so well armed and so richly apparelled in cloths of gold and silver and velvets of sundry colours, pounced and embroidered, and all petty captains in satin and damask of white and green and yeoman in cloth of the same colour, the banners, pennons, standards. . .fresh and newly painted with sundry beasts and devices, it was a pleasure to behold.

When news arrived in June of the successful landing of Dorset and his 10,000 men at San Sebastian, near Biarritz, Henry ordered a celebratory joust at Greenwich. This was followed by a naval review at Portsmouth for Henry to inspect his fleet and send forth the chivalric brotherhood on further triumphant enterprises: ‘The king made a great banquet to all the captains and everyone swore to another ever to defend, aid and comfort one another without failing, and this they promised before the king, who committed them to God, and so with great noise of minstrelsy they took their ships.’

Howard led his fleet on a seek-and-destroy mission to locate and eradicate the French marine. At the beginning of August 1512 he tracked the enemy down to the well-fortified port of Brest and, on the 10th, his opposite number, Hervé, Sieur de Portzmoguer, came out to offer battle. Warships at this time were not gun platforms designed to pound the enemy to pieces but troop carriers whose captains tried to grapple and board the opposition vessels. It was while Henry’s capital ship, the Regent, was thus shackled to the French carrack, Marie La Cordelière, that a horrific incident occurred which shocked both combatants and put a swift end to the action. Either by accident or design, the Cordelière’s powder store was ignited. Within moments both the ships, locked in a deadly embrace, were blazing. Officers and men were doomed to burn to death or drown since the heat was too intense for other ships to rescue them. Seven hundred English sailors perished and among them was Thomas Knyvet.

Reporting these ‘lamentable and sorrowful tidings’ to his mentor Bishop Fox, Wolsey urged him to keep the news secret, commenting that ‘only the king and I’ were party to the full details. He went on, ‘To see how the king taketh the matter and behaveth himself, ye would marvel, and much allow his wise and constant manner. I have not on my faith seen the like.’ We would expect Wolsey to praise the king’s stoical self-control and it is frustrating to have no other indication of Henry’s true feelings at the loss of his friend. Did he privately nurse a deep grief or were other emotions uppermost as he received bulletins on the progress of the war? They were far from reassuring. Dorset and his men were effectively trapped in the environs of St Jean de Luz. Immobilized by lack of supplies and by divided counsels. Ferdinand failed to send the men and equipment he had promised. He also tried to persuade Dorset to march his army south over the Pyrenees. The English commander refused to abandon his instructions, which were to move north and invest Bayonne. The result was that he did nothing. His demoralized troops fell prey to idleness and dysentery; some 1,800 died. Eventually, they mutinied, demanding to be taken home. Dorset, now ill himself, yielded to them. Henry was incandescent. He wrote to Ferdinand asking him to prevent the English troops abandoning their enterprise but his instructions arrived too late. Howard, meanwhile, was raiding along the French coast, burning, looting and capturing enemy ships in an orgy of revenge. In a message to Wolsey, he vowed never to return to court until he had made the French pay heavily for Knyvet’s death.

It is scarcely surprising that Howard was in no hurry to face the king. The expedition which had started out so bravely had all gone horribly wrong and Henry, as he well knew, did not like losing. Dorset, on his return, went to his country estates, claiming to be too ill to present himself at court. Whether his affliction was physical or diplomatic, he was well advised to maintain a low profile. Back at Greenwich his subordinate officers were being put through the mincer of royal wrath. Ferdinand had sent envoys roundly blaming English incompetence for the Guyenne debacle and Henry, not wishing to offend his ally, accepted the Spanish analysis – officially, at least. Several of the English captains were subjected to a humiliating ‘trial’ in front of Ferdinand’s representatives. Henry cowed them with threats of stringing them up from the highest gallows but no punishments were subsequently handed out. They may well have considered themselves hard done by. They had supported Dorset in refusing to depart from the strategy outlined by the king. Their inability to carry out that strategy had been entirely due to Ferdinand’s failure to stick to his side of the bargain.

What does emerge from this sorry sequence of events is Henry’s tendency, even at this young age, to use anger – often theatrical – to cow those who provoked his displeasure. It was an effective weapon, even when turned on those who knew him well. It silenced offenders, precluded further debate and absolved the king from calmly weighing up the pros and cons of complex problems. It was to become a feature of all Henry’s relationships over the years. He was not yet given to the towering rages which would mark his later years. Rather, he displayed his disapproval in petulance and the sulking withdrawal of favour. His ministers, diplomats and captains were increasingly motivated less by a desire to please him than by the desperate need not to displease him. While this undoubtedly drove royal servants to achieve results which would not have been possible under the rule of a more even-tempered monarch, it could also be counter-productive. Ambassadors in far-off capitals or generals on distant battlefields who were in the best position to decide how to respond to changing situations effectively had their hands tied by fear of exceeding the instructions they had received from the king. Thus, individual initiative and creativity was stifled.

In the spring of 1513 Edward Howard, embroiled in the frustration of another inconclusive naval campaign and knowing how impatiently Henry would be waiting for good news, had the temerity to invite the king to come and take charge of the action for himself. Of course, he wrapped up the challenge in suitably flattering words: Henry’s presence would ensure victory, he suggested. He was really saying: ‘Instead of grumbling, come and see for yourself what it is like out here.’ His invitation, needless to say, received a curt reply.

Within weeks Howard became another member of the ‘Round Table’ to lay down his life for the king. Somewhat like a losing gambler who goes on throwing the dice in the conviction that his luck will change, Henry pledged himself to a continuation of the war. This time he upped the stakes. He would personally lead an army to invade northern France. If a force of 30,000 was to be safely conveyed to Calais it was essential, first of all, to clear the Channel of French ships. This was the task assigned to Howard in the spring of 1513.

Once more he located the enemy fleet at Brest. This time the French declined an open battle, preferring to sit it out in their safe haven until their opponents were forced, by weather or shortage of victuals, to withdraw. They would not come out of port and Howard could not get in. When he tried, one of his capital ships came to grief on the rocks. The stalemate continued for two weeks; a battle of nerves. It was Howard who broke first. Knowing how the king would interpret his continued inactivity, he resolved on a typically rash, death-or-glory escapade. He launched an attack by rowing boats across the shallow waters of the anchorage. He and his men reached and boarded the French admiral’s ship. Fierce hand-to-hand fighting ensued but the attackers were greatly outnumbered. Howard was among those forced over the side where he drowned in the water, weighed down by his armour. His dispirited captains upped anchor and sailed for home, while the French sallied forth to raid at will along the Sussex coast.

It is not recorded that Henry stoically contained his grief. He was, in fact, far more concerned at the threatened disruption of his master plan. His immediate reaction was to appoint Edward Howard’s brother, Thomas, to take his place, put some fight back into his men and execute the pre-ordained strategy without any more bungling. Thomas was an altogether more cautious man than his sibling. Whatever else he did, he made sure to watch his back. As day followed frustrating day in Plymouth, where he was supposed to be mustering his force, the admiral bombarded Wolsey and the king with letter after letter excusing the delay and blaming everyone except himself. The ships needed repair. The sailors were too cowardly. Supplies were sub-standard or non-existent. He even rode to London himself to explain the situation in person. To his chagrin, neither the king nor his almoner would see him. It was the end of June 1513 before Howard was able to bring his ships round to the Thames estuary to escort Henry and the main part of the invasion fleet.

Henry would always claim the 1513 campaign in France and Scotland as a great personal triumph. It was nothing of the sort. The vanguard of the army, led by Charles Brandon, and the rearguard under the command of Charles Somerset, Baron Herbert (the long-serving councillor Henry had inherited from his father), had already crossed the Channel by the time Henry began his stately progress through Kent, attended by his liveried guard of 600 spearmen and a mile-long retinue of splendidly accoutred nobles with their own levies that wound its way along dusty lanes and through villages of jingoistic countrymen who had turned out to cheer their champions setting out to bash the ‘frogs’. Before embarking, Henry had a nasty surprise for the Howard clan. Thomas and Edward’s father, the Earl of Surrey (also called Thomas) was Earl Marshal and assumed that an honoured place would be found for him in this prestigious enterprise, but he had opposed Henry’s expansionist ambitions. He had been at odds with his younger son, Edward, who had valiantly laid down his life in the service of his king. As for the older boy, Thomas, he had scarcely given an impression of competence in handling the maritime arrangements. Henry now took delight in informing Howard senior that he was not to join him in France. Instead, he was to make his way to England’s bleak and distant northern border. It was known that James IV of Scotland would support his old ally, the French king, by making trouble in the Marches. Surrey was now detailed to contain the expected incursion. Later, Thomas and his remaining brother, Edmund, were detached from the army in France to go to their father’s aid. It was an important commission but it was not the high profile one Surrey had hoped for and it lacked any semblance of glory. Whatever his private feelings about Henry, Surrey publicly vented his ire on the Scottish king. ‘Sorry may I see him,’ he told his companions, ‘or die that is the cause of my abiding behind, and if ever he and I meet, I shall do all that in me lieth to make him as sorry if I can.’38 Reluctantly, the earl took his leave of his glory-seeking sovereign. Neither could anticipate the irony that would unfold over the ensuing weeks.

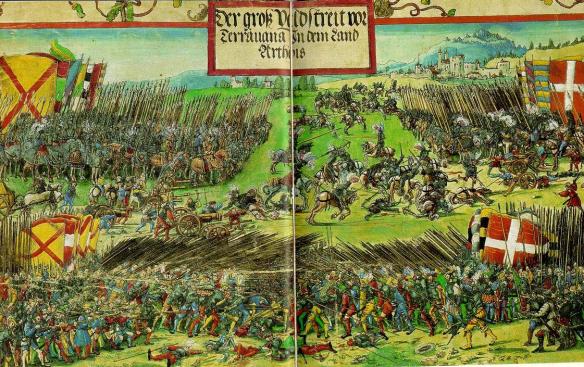

The English army besieged and captured with relative ease Thérouanne in Artois and Tournai, a city in Flanders which Louis had taken from the Emperor. The only battle in the field occurred when a French relieving force was put to rout, an engagement contemptuously referred to by the victors as the Battle of the Spurs because of the speedy withdrawal of the enemy. It was old-fashioned warfare fought largely in accord with chivalric convention. Can it have been entirely coincidental that insignificant Thérouanne was a mere 20 miles (30km) from Agincourt or that the king made a nocturnal tour of the English camp putting heart into his men, as Henry V had done before his famous battle? The only immediate advantage to the English was the capture of several prominent and eminently ransomable French notables. Henry’s ‘great battle’ could scarcely have been more different from the one his father had won at Bosworth, hazarding himself in the clash of arms to snatch a crown, but it was a victory and one he was determined to trumpet loudly. Meanwhile, he had left Queen Catherine as his regent during his absence and she it was who energetically prosecuted the war against the Scots.

On 22 August 1513, James IV crossed the border with a force of about 30,000 men, including a small contingent provided by his French ally. (In his reports Surrey inflated this figure to more than 80,000.) Surrey had been energetically recruiting and had around 20,000 troops to face the invasion, but this was only part of the national response. Catherine and the council had reacted industriously and intelligently to the threat. Sir Thomas Lovell, a seasoned Tudor servant who held various offices including Constable of the Tower and Steward of the Household, was ordered to gather men in the Midland counties as a second line of defence. For her part, the queen became a veritable Boudicca, riding from Richmond to the muster-point at Buckingham at the head of a third army behind bravely fluttering banners, some of which she and her ladies had sewn themselves.

In the event, her mettle was not tried in battle because the Scots were halted some 2.5 miles (4km) south of the Tweed on the heights above Flodden Field. The English victory at the Battle of Flodden (or Brankston Moor) on 9 September was the result of a rare flash of tactical brilliance on the part of the Howard leadership, combined with the rash incompetence of the Scottish king. It may also indicate the gulf between chivalry and the bloody reality of war. According to legend, James refused to allow his artillery to blast the enemy to pieces as they struggled across the marshy terrain on the grounds that it would be ‘dishonourable’. He allowed himself to be lured from his commanding position in the hope of winning the day in a downhill cavalry charge. Howard had been counting on such a headstrong response in order to achieve the pitched battle his disciplined men were equipped to fight. Even so, the conflict was long and bloody and went on until evening. By the time the Scottish standards were captured, the king, several of his nobles (the ‘flowers of the forest’ long-remembered in minstrelsy) and some 10,000 soldiers lay dead on Flodden Field.

It was one of the major turning points in Anglo-Scottish relations. For the rest of Henry’s reign the demoralized Scots were in no position to intervene effectively in affairs south of the border. James was succeeded by an infant son whose regency was vested in Queen Margaret, Henry’s sister. The result of Flodden was, therefore, much better than the king could have hoped for. It removed one irritating chess piece from the complex board of foreign policy. However, it was also a personal embarrassment. It was obvious to anyone who calmly assessed the recent military activities that the Howards’ achievements had put Henry’s in the shade. No one, of course, said as much openly. Quite the contrary. When Catherine forwarded to her husband a fragment of James’ bloodstained surcoat (tunic), she was careful to affirm that the triumph was Henry’s, carried out in his name and for his glory.

After taking possession of Tournai on 24 September, the victor spent three weeks in lavish displays of celebration. The Howards were not invited to come and join in the festivities and when, subsequently, Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, was awarded the dukedom of Norfolk (a title which had been stripped from the Howards by Henry VII), he had to share the investiture with the captains of the French campaign, Charles Brandon, who became Duke of Suffolk, and Lord Herbert, who was elevated to the earldom of Worcester. However, no one shared more handsomely in the fruits of victory than Thomas Wolsey. He was appointed Bishop of Lincoln and Bishop of Tournai (a position he later relinquished in return for a pension of 12,000 livres). Negotiations began in Rome for his elevation to the cardinalate. And before 1514 was out, he had become Archbishop of York.

More cold water was poured on Henry’s achievements by the behaviour of his allies. It had been agreed between the rulers of Spain, England and the Holy Roman Empire that their league against France would continue and that it would be cemented by a marriage between Henry’s sister, Mary, and Charles, ruler of the Netherlands, who was the grandson of both Maximilian and Ferdinand (and, therefore, Queen Catherine’s nephew). It was an impressive diplomatic coup, signifying clearly that Harry of England had ‘arrived’. By the spring of 1514, though, it was all off. Ferdinand and Maximilian had made a truce with Louis. This time Henry was not prepared to ride the diplomatic punches; he hit back. After the events of recent months he had more standing in the councils of Europe – and he also had at his elbow an arch-intriguer, well able to play the game of deception and counter-deception. Wolsey knew that England could not afford an open-ended commitment to war. The country needed an honourable peace. Possibly, the achievement of this had been his goal all along; having given the king his moment of glory he may well have entertained hopes of steering him into more irenic and positive policies. He was already using his influence in Rome where the death of Julius II in February 1513 and his replacement by the Medici, Leo X, had inaugurated a very different regime.