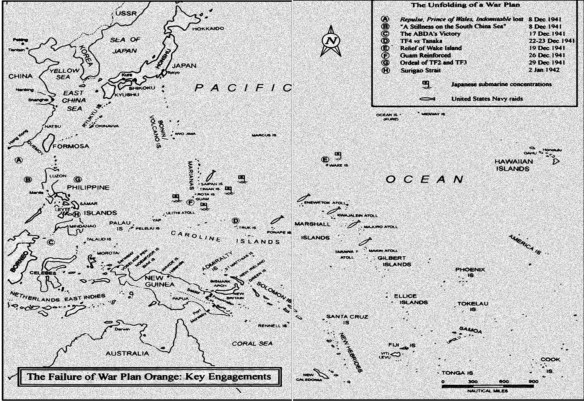

The Failure of War Plan Orange: Key Engagements

Truk-ing

It’s a military truism that no plan survives contact with the enemy, and it was certainly as applicable to Plan Z as to the ill-fated Plan Orange. Yamamoto faced two unexpected problems: the ABDA command reinforced by Yorktown, and TF 4 rampaging through the Marshall Islands. Both moves caught the Japanese admiral flat-footed (Yamamoto strongly believed that the USN would sensibly mass its carriers for battle) and demanded immediate attention.

Operating from secure bases in the Netherlands East Indies, the ABDA task force pushed tentatively northward on December 8, threatening to disrupt the valuable convoys supporting the invasions of the Philippines and Malaya. Two days later Yamamoto dispatched a task force centered around the slightly damaged Ryujo and the light carrier Hosho to counter the threat. On December 17, after a week of sparring, fighters and bombers from Yorktown caught the Japanese carriers in the process of launching a strike against the ABDA task force. In the face of stiff resistance from a reinforced enemy CAP (fighters were already aloft for the planned strike against Yorktown), American dive-bombers hit Hosho five times, while two torpedoes and three bombs turned Ryujo into a flaming hulk. But this victory had a stiff price—Yorktown expended seventy-three planes in the attack, including all of its torpedo bombers and over half of its fighters. Adm. Karl Doorman, aboard the cruiser De Ruyter, had little choice but to order withdrawal until the depleted air wing could be reinforced; especially after Japanese submarine 1-17 sank Langley (once designated CV 1, then redesignated AV 3, an aviation transport), ferrying replacement aircraft to Yorktown, on December 19. Nonetheless, the ABDA provided the only true victory for the Allies during the brief Pacific War.

Unless he chose to weaken his Fast Strike Force, Yamamoto lacked carriers to send against the U.S. task force raiding through the Marshalls. Still, the fleet base at Truk, an obvious target for the Americans, offered an opportunity to attrit the USN. On December 9, Yamamoto dispatched a light force led by Rear Adm. Raizo Tanaka in the cruiser Jintsu to Truk. It included two additional cruisers, Myoko and Nachi, and eight destroyers. Tanaka had orders to attempt to develop a night action if the Americans approached the base.

Slowed by a boiler failure on the hastily commissioned Washington, TF 4 did not enter strike range of Truk until December 22. Even then, Halsey hesitated to commit his dwindling air group against a possibly heavy Japanese air defense. Holding a cruiser and four destroyers back to defend Enterprise, the admiral ordered the remainder of the task force to close and bombard Truk under cover of darkness. Capt. Tameichi Hara, skippering the destroyer Amatsukaze, describes what followed:

A seaplane reported two American battleships [North Carolina and Washington], two cruisers, and six destroyers steaming directly to Truk shortly before dark on December 22. Tanaka, perhaps the best in our navy at night actions by small ships, deployed us in parallel lines, an interior of three cruisers led by two destroyers, and an exterior of six destroyers. At 1123, [destroyer] Kuroshio spotted shapes approaching the front of our column at about 48°. A cloudy night, the Americans had approached to less then 3,000 yds before being spotted! Strangely, they seemed not to see us at all, until our division unleashed 48 torpedoes and turned quickly to port for reloading. At that instant star shells burst above the enemy battleships, and the leader, the North Carolina [actually the cruiser Chicora], was hit by concentrated fire from our cruisers. I was busy for the next few seconds as shell splashes swamped my frail vessel. The Kuroshio was not so lucky—at least one large caliber shell penetrated a magazine and it seemed to lift completely from the water. Seconds later, Murata [a spotter] screamed, “Hits! Torpedo hits along the line!” My heart almost stopped before I realized that he meant the enemy line, and not ours … By 0058, it seemed that the sea was covered in burning ships. A large American vessel, obviously out of control, bore down on us. I ordered our 5-inch guns to open fire—a mistake as an enemy cruiser quickly hit us once the flashes revealed our position, our first damage of the engagement… At 0153, Jintsu, burning and dead in the water, flashed a message to launch remaining torpedoes and disengage. It grieved us to so abandon our comrades, particularly my friend and mentor, Tanaka . . .

Clearly, our success against the vastly superior American force resulted from our constant training in night combat actions and proper use of the torpedo, aspects of war neglected by the enemy. But given time, the USN could match the training, if not the warrior spirit, of the Imperial Navy. Thus the advantage of our grossly outnumbered ships would be fleeting—I prayed to my ancestors that it would last long enough for Yamamoto to crush the enemy’s main battle line…

In the confused night action at Truk, both American battleships suffered severely. Each took two torpedoes, Washington’s already slow pace dropping to fifteen knots. All three USN cruisers sank before dawn, along with three destroyers. Halsey had little option except to return to Pearl—abandoning the damaged battlewagons to join Kimmel would result in their destruction. Even then, IJN submarine 1-221 managed to penetrate TF 4’s reduced ASW (antisubmarine warfare) screen and sink Washington on December 25.

Admiral Tanaka, his flagship reduced to a hulk by numerous large caliber hits, actually survived the battle, the vessel towed to Truk the following day. The other Japanese cruisers and three destroyers were not as lucky. Tanaka shifted his flag to Amatsukaze, and having effectively stripped two battleships and a carrier from the American fleet, began moving his battered survivors to join Yamamoto off Luzon for the final showdown.

What Damn Carriers?

Task Force 1 reached the vicinity of Wake Island on December 19, shortly after Kimmel received a belated notification of Yorktown’s successful action against the Japanese light carriers. Though Kimmel should have been puzzled by the failure of the IJN to seize the lightly defended islands of Guam and Wake, he apparently wrote the matter off to Yamamoto’s incompetence as a naval commander (perhaps understandably—Kimmel was operating under the delusion that Japan had lost as many as eight carriers). The task force tarried only briefly in the vicinity of Wake, and then only because of a torpedo hit on the old battleship Texas (screening forces sank three IJN submarines in the area, of which only one managed a torpedo attack). The battlewagon’s crew quickly fixed a temporary patch over the gaping hole in its bow, allowing it to remain with the task force when the latter turned for Guam on December 20.

As TF 1 neared Guam, IJN submarine contacts increased. By December 26, when the APDs unloaded their Marines as reinforcements for Guam’s defenders, screening destroyers had defeated over a dozen attacks. Despite four confirmed kills, exhaustion took its toll, and 1-214 at last managed to hit Nevada with four torpedoes before being forced to the surface and rammed by the destroyer Manley. Though valiant damage control efforts saved the battleship from sinking, its propellers and rudder had been smashed. When Kimmel began the last stage of his voyage on December 27, both Nevada and Manley remained at Guam. The APDs also stayed, to screen the damaged battleship.

Brown’s Task Force 2 and Fletcher’s Task Force 3 failed to find a single Japanese vessel in their rush across the Pacific, though Lexington’s air group bombed and strafed the small Japanese airfield on Saipan on December 24 and 25. War Plan Orange had called for the carrier task forces to close with TF 1 on the final leg of its journey, but Kimmel, thinking the threat from enemy naval aircraft had been minimized signaled Brown and Fletcher to unite their task forces on December 29, approximately 300 miles due west of Legaspi airfield on Luzon. They would then proceed, under Fletcher’s command, to the Formosa-Luzon gap, fixing the position of the IJN Combined Fleet for Kimmel’s rapidly approaching TF 1.

Had the carriers united at 0800 December 29, as ordered, a thin chance existed that they could have survived the onslaught that overwhelmed them individually; but Fletcher, on December 28, had again slowed TF 3 for refueling, despite the fact that the Saratoga’s tanks were well over half full. His first indication of a problem came at 0937 on the following day, while still eight full hours south of TF 2. When given a radio message from Lexington that read, “Under attack by large numbers of Japanese carrier planes. Where is TF 3? All the world wonders,” Fletcher could only exclaim, “Carrier planes! What damn carriers can they still have?” At last ordering the task force to full speed, Fletcher revectored his search planes and tried to contact Brown’s force.

The world will never know exactly what happened to TF 2. How did Vice Adm. Chuichi Nagumo’s “Ghost Fleet,” the six carriers of the Fast Strike Force, manage to surprise Wilson? Why did Nagumo continue to pound the task force after Lexington sank? And why was no effort made to rescue the thousands of survivors abandoned in the shark-infested Pacific waters? What we do know is that a carrier, three cruisers, eight destroyers, and two fast oilers succumbed to eight hours of repeated air attack. The suffering of their crews, until taken by the sharks or succumbing to dehydration, is perhaps better left unimagined.

The death of Saratoga seems almost anticlimactic after the horrors experienced by TF 2. At 1628 on December 29, one of Fletcher’s scouts (before being destroyed) reported four Japanese heavy carriers approximately 250 miles west-northwest of TF 3. Fletcher quickly launched a full strike, retaining only six fighters for CAP. While getting the strike into the air, Saratoga’s CAP killed a Japanese flying boat, but only after it had reported TF 3’s position. Though Nagumo’s fliers were exhausted after destroying TF 2, he nonetheless managed to deploy a small striking force of eight torpedo planes, twelve dive-bombers, and nine fighters (none would find their way home in the gathering darkness). These found Saratoga at 2010, quickly overwhelmed its CAP, and sank the carrier with three torpedo and at least four bomb hits. Fletcher died on his bridge. The remainder of TF 3, crowded with Saratoga’s survivors, made full speed for Guam. As for the American air group, it reported sinking two carriers attempting to hide in a rapidly advancing storm front, then disappeared plane by plane as each exhausted its fuel. Though Nagumo reported 112 of his 497 available planes lost on December 29, he never mentioned a U.S. attack on his force. Ironically, the two carriers reported destroyed by Saratoga’s air group may well have been the oilers attached to TF 2.

Der Tag

In the early hours of December 30, an exhausted Kimmel received word of the loss of Saratoga. With no word from Task Force 2, and every indication that Yamamoto had more carrier strength than originally thought, Kimmel was caught in a dilemma. Task Force 1 was only forty-eight hours from Luzon at top speed, and less than eighty hours from a presumed safe anchorage at Manila. To turn tail at this point would mean not only admitting the failure of War Plan Orange, but would not guarantee a safe return to Pearl for his battle line, which was mainly intact and still outnumbered the Japanese. Standing on the bridge wing of Arizona, accompanied only by his aide, Zumwalt, Kimmel talked aloud as he worked through his options. “First, Yamamoto will be waiting north of Luzon, guarding his convoys. Second he must have expended the last of his naval air today—what’s he got left, Zumwalt? A couple of escort carriers? Third—well, third I’ll be damned if I want to be remembered as a Scheer! You know that story, Ensign? From 1914 to 1916 the German navy waited for ‘DerTag’—’the day,’ when it would challenge the British fleet in one last battle, to victory or to the last ship. But the Germans never really had the advantage, and when Scheer finally had his chance at Jutland he turned and ran. I still have the advantage, Ensign! This is the most powerful battle line afloat, and I just can’t see running away with it.”

So Kimmel, wishing to avoid the condemnation of future naval historians, continued to Manila. Without air cover, however, he decided to use the most direct route to his anchorage— via Surigao Strait. Unfortunately, Kimmel and the remaining ships of TF 1—nine battleships, three cruisers, and seventeen destroyers—already stood among the damned thanks to the American public, a faulty War Plan Orange, and the genius of Yamamoto.

The Gauntlet

On December 30, shortly after being advised of the sinking of the last American carrier supporting Kimmel, Yamamoto ordered Nagumo to slowly scout southward find the USN’s battle fleet, and drive it to Surigao Strait. Nagumo did just that, using December 31 to rest and reorganize his weary but jubilant air groups. At 1143 on January 1, 1942, his scouts discovered the American fleet steaming at best speed for Luzon. Through the rest of the day, amid constantly deteriorating weather conditions, Nagumo managed to launch only two waves of planes against Task Force 1. One of these never found Kimmel’s fleet, and the other sank the cruiser Vincennes and two destroyers, disabled the aft turret on New Mexico, and started severe fires on Oklahoma and Tennessee. As darkness fell, Nagumo moved northwest and counted his losses: an additional seventy-two planes had fallen victim to heavy antiaircraft fire or accident, bringing his two-day losses to 184 of the 497 original aircraft. Secure in the knowledge that the fate of the American battle line now rested in the hands of his brilliant boss, Nagumo sailed for a rendezvous with invasion forces to be aimed at Guam and Wake Island.

With darkness more or less cloaking his battered TF 1 (both Oklahoma and Tennessee still flamed), Kimmel organized his fleet for a rapid advance through the relatively narrow waters of Surigao Strait. Three destroyers picketed his van of cruisers, Chicago and Augusta, followed closely by Idaho, New Mexico, and California. About a thousand yards separated the van from the remaining battleships led by Kimmel in Arizona, and trailed closely by the two burning vessels, shepherded by four destroyers. The remaining two destroyer divisions deployed 1,500 yards to port and starboard of the van. By 0130 on January 2 it appeared that TF 1, including the laggard battlewagons whose exhausted crews were at last getting the best of fires fed by prewar paint and furnishings, had negotiated the confined waters successfully.

Yamamoto had quietly gathered his Combined Fleet of six battleships—commanded by himself from the super-battleship Yamato—eight heavy cruisers, four light cruisers, and forty-two destroyers. Through the storms of January 1, his heavies, screened by a light cruiser and twelve destroyers, steamed back and forth across the west entrance to Surigao Strait. Closer to the entrance, three divisions of ten destroyers, each led by a light cruiser, waited to box the approaching task force. The weather had concerned Yamamoto, despite his commanding position and preponderance of light ships, but the front passed at midnight, and a floatplane launched from the cruiser Tone reported the Americans steaming full tilt through the narrow waters with two burning vessels trailing the main force. At 0148 on January 2, sitting firmly across the American T at a range of only 12,000 yards, Yamamoto flashed the code words, “Tora! Tora! Tora!” This signaled his destroyers, stealthily advancing along the flanks of TF 1, to launch their torpedoes at the enemy. The words of Captain Hara, whose Amatsukaze (still bearing the scars of the action at Truk) was in the division of destroyers some 4,000 yards to port of the American formation, capture the action:

Tiger! Tiger! Tiger! The moonless night and the dark shore to our rear hid us from the enemy as our division alone launched over eighty Long Lances at the enemy line. I targeted the third and fourth battleships in their second echelon. Within seconds, and long before our torpedoes would reach their targets, water spouts began to erupt among the enemy van and second echelon. Hits came quickly, the two burning ships at the rear, Oklahoma and Maryland [actually Tennessee] outlined those vessels in front of them. The Americans appeared to panic, two destroyers colliding in their port division—confusion to which we added with my gun crews’ rapid fire… Then the American battle line disappeared in a wall of water and flame! Apparently the torpedoes from both our port and starboard board divisions arrived at the same time. As the mist and smoke cleared, one American battleship had simply disappeared [West Virginia], a second was turning turtle [Maryland], and a third, minus its bow to the first turret, was surrounded by burning oil and rapidly settling [California].

Later I learned that every American battleship had been struck by at least one torpedo, and quite probably one cruiser and at least five destroyers had also been lost to our opening volley. Then and there I resolved never again to ship aboard a battlewagon. After this, my second night in action, I knew that the Long Lance had ended their day of ruling the waves …

What Hara had viewed as panic was instead the result of two large caliber shells, probably from Haruna, striking the bridge and flag bridge of Arizona. Every man on the bridge died immediately, and the flagship, helm untended, began a gentle turn to starboard. Though control of the rudder was restored in minutes, the damage had been done. The remaining vessels of the second echelon, as well as the destroyer division to port, apparently became confused as they tried to follow the unannounced maneuver.

Worse for TF 1, the salvo had mortally wounded Kimmel, who died within seconds, apparently after whispering his last commands to Ensign Zumwalt. Then, for the first time in history, an ensign took command of a modern battleship in combat. As flames raged through the superstructure of Arizona, Zumwalt, severely wounded himself, ordered a petty officer to send a message to the fleet ordering independent advance to Manila at best speed. Afterward, he made his way, with two ratings, to the bridge. Discovering both wheel and intership communications intact, Zumwalt took control of the battleship, conning it through Yamamoto’s line and to Manila Bay while in constant danger of being roasted alive or falling unconscious from loss of vital fluids. Nor did Arizona flee without drawing Japanese blood; its surviving guns turned the cruiser Yubari into a sinking mass of scrap, and Zumwalt actually managed to ram the destroyer Shirakumo, cutting it completely in half as Arizona escaped Yamamoto’s trap.

Along with the flagship of TF 1, two destroyers and a miraculously undamaged Augusta escaped. Texas, closely following Arizona, also penetrated the Japanese battle line, but capsized an hour later when the patch that its crew had hastily installed off Wake Island gave way and added tons of water to what it had already taken on from two additional torpedo hits. If not for the heroic efforts of the van battleships, Idaho and New Mexico, none of these vessels would have escaped. With Idaho’s speed reduced to half by flooded boilers, Capt. Mark Smith turned his ship to parallel Yamamoto’s battlewagons rather than attempt an escape. Capt. Edward Coombs in New Mexico, despite a fourteen degree list that prevented his remaining primary guns from firing, followed. For a vital half hour the two vessels absorbed the fire of six Japanese battleships and their screen, while Smith pounded battleship Mutsu and Coombs’s secondaries lashed at any enemy vessel in range. As Mutsu drifted out of control, sinking (the only Japanese capital ship lost in the action), New Mexico finally succumbed to its earlier torpedo hits and rolled onto its side at 0222. Less than a minute later, a shell from Yamato apparently penetrated the aft magazine of Idaho. It broke into two sections and sank in minutes.

In the rear of TF 1, Oklahoma and Tennessee had never recovered from the damage inflicted the previous day by Nagumo’s air strikes. With several magazines voluntarily flooded on January 1, numerous secondary casemates ravaged by fire, and additional flooding from the opening barrage of Japanese Long Lances, the battleships attempted to disengage to the west. After destroying the American van, Yamamoto pursued. By 0430 both battleships and their escorts had succumbed to a barrage of torpedoes and large caliber shells.

Dawn found the waters of Surigao Strait smothered with the detritus of battle;—oil, lingering smoke, odd bits of wreckage, and sailors both living and dead. His victory won, Yamamoto counted his losses—one battleship, one cruiser, and fourteen destroyers—and then continued the war. The Japanese made only minimal efforts to rescue American survivors, though hundreds managed to drift ashore over the next four days. Most were immediately taken prisoner by the enemy, less than a hundred reaching the steadily diminishing territory controlled by MacArthur’s now demoralized army.

For the four surviving vessels of TF 1, Manila failed to provide the anticipated refuge. Their trial by fire continued. On January 4 a massive raid by Japanese land-based bombers resulted in a magazine explosion on Arizona. Sheathed in fire, it rapidly settled in the shallow mud of the harbor. The following day, both destroyers fell prey to torpedo bombers. Somehow, Augusta again managed to survive the carnage unscathed only to be scuttled by its crew on January 6, the day MacArthur finally abandoned the port.

A Day That Will Live in Infamy

On January 7, 1942, President Roosevelt authorized the release of information pertaining to the defeat of the American fleet in the Philippines. Panic swept through the United States, a nation that had never experienced sudden defeat on such a scale. Thousands of American families wept for the fathers and sons feared lost to enemy action. Newspapers fed panic and fear with rumors of Japanese fleets off the Hawaiian Islands and the Pacific coast. Radio commentators listed the few vessels remaining in the Pacific Fleet between their reports on Axis successes in Europe. And in Washington, Roosevelt and his advisors wrestled with one of the most difficult decisions ever faced by an American government.

They recognized that it would take months, if not years, to replace America’s matériel losses. Even then, the loss of naval cadre would lead to difficulties in training recruits to man the new ships. In addition, in prewar discussions with Great Britain, Roosevelt had already committed the United States to a “Germany First” strategy. Moral issues (and many existed) aside, fascist domination of Europe would hamstring the American economy, only just recovering from the Great Depression. The Philippines and U.S. islands near Japan could not be defended without a strong navy, nor could the United States provide adequate aid to the struggling British Commonwealth in the Pacific Theater without ships. Could Japan successfully invade Hawaii? Probably. Could it invade the West Coast of the United States with Hawaii secured as a fleet base? Probably not—but the UN could eradicate American shipping in the Pacific, shipping that provided raw materials to much of U.S. industry. On the other hand, could Great Britain survive Germany’s U-boats without the assistance of American shipping and the U.S. Navy? Possibly not. Would the American people fight? Could they rally from the fear and panic sweeping the nation? Absolutely! Ultimately, Roosevelt was left with one key question: Could the United States successfully lead the effort to free Europe from Axis domination while simultaneously fighting a war against Japan, a war that threatened American shores, a naval war that would drain men, matériel, and national wealth at an abominable rate?

On January 12, 1942, after a final meeting with representatives of the British government, an exhausted President Roosevelt ordered MacArthur to seek a cease-fire and, in conjunction with British representatives in the Far East, open negotiations with the Japanese government. One month later, in words now immortal, he addressed the American people: “On February 12, 1942, a day that will live in infamy, General Douglas MacArthur and representatives of our European allies signed an armistice with Japan aboard the Nevada at Guam. This peace is necessary so that we may lead the struggle against fascism in Europe; but we shall never forget Surigao!”

War Plan Orange had failed. Japan claimed the Philippines as prize, though it allowed the United States to retain Guam and Wake Island (both demilitarized). Great Britain reluctantly agreed to a phased withdrawal from the Far East in exchange for trade concessions with India and guarantees that Australia and New Zealand would not suffer invasion. By the waning days of 1942, Japan managed to establish its Greater Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere, stretching from the Gilbert Islands to Indonesia, India, and China. With the collapse of Germany in early 1945, the world quickly polarized—Japan and its puppets arrayed against the rest of the world, led by the United States, Great Britain, and their uncomfortable communist bedfellow, the USSR. Winston Churchill’s 1947 speech, in which he referred to a “Bamboo curtain descending across Asia and the Pacific,” is generally taken to mark the beginning of the brief East-West Cold War that culminated in the wave of internal revolutions led by such heroes as Mao, Gandhi, and Ho, and in the misnamed Sixty Minute War of 1953. But that, as the storyteller invariably says, is another story.

The Reality

It is difficult to imagine any simple set of circumstances that would have allowed Japan to win any form of victory in World War II. Even Yamamoto, its premier naval strategist, knew that the industrial might of the United States must prevail in the long run. For Yamamoto, Pearl Harbor seemed the best chance in a very desperate scenario. And Pearl Harbor was little more than a bee sting on the foot of a sleeping giant, awakening both an industrial power and personal commitments to victory among Americans that eventually doomed Japan while allowing the United States to support their allies in the destruction of European fascism.

Only military rashness of an improbable nature could have offered Japan an opportunity of victory. To tie that rashness to U.S. politics seems more than reasonable in a nation where civilian guidance governs the ultimate deployment and strategy of its military forces (too often to the detriment of young, underpaid, and frequently unappreciated American servicemen). Everything following Roosevelt’s decision to implement a long-abandoned and seriously flawed version of War Plan Orange is, of course, fiction. In reality, the United States closely followed its prewar plan of a gradual erosion of Japanese power, which would have culminated in the invasion of the home islands had not the atomic bomb interfered. Fortunately, the discovery of the true industrial potential of the United States accelerated the course of the Pacific War—matériel was available to maintain Europe as first priority while still overwhelming Japan with ships, planes, and bombs.

A final idea (critical to this hypothetical victory) that must be addressed is the concept of civilian morale, or the “national will” to continue a struggle. War has definite learning curves associated with it. We are familiar with those present on the field of battle; the techniques, for example, that once learned, enhance individual survival. But civilians far removed from the field of battle seem to have a learning curve as well, a process of gradual inurement to increasingly long casualty lists as well as to individual material sacrifice. In reality, Pearl Harbor was a small shock that began a process of acclimatization to war. Without small shocks to prepare them for greater losses, could the American will to resist have been temporarily weakened by the horrific losses postulated in this alternative line of history? Quite possibly; at least, that will could have been weakened enough to accept a rapidly negotiated peace—which in the end was Japan’s only real hope for victory in the Pacific.