Essex launched her major morning strike at 0715 hours, led by new CAG Commander Upham at the head of 16 Avengers from Torpedo-4, 15 Hellcats from Fighting-4 and 16 Marine Corsairs led by Major Fay V. Domke and Captain Edmond P. Hartsock; their target was Naha Airfield on the west coast of the island. Over the target, Corsairs strafed antiaircraft positions to silence the defenses, followed by the Navy Hellcats. The Avengers made their glide-bombing attacks while the fighters returned for repeated strafing runs.

Essex sent a second strike against Naha with VMF-213’s Major Marshall leading 16 Corsairs, eight Hellcats and 15 Avengers. This attack was hindered by adverse cloud conditions. VF-4’s Lt(jg) Doug Cahoon was hit by flak; his Hellcat exploded on impact. The tail of the Avenger flown by Lt(jg) Scott Vogt was blown off by flak just as he dropped his bombs. As the bomber crashed on the airfield, one parachute was seen to open.

Air Group 4 pulled off from the attack and trapped back aboard to complete the last combat mission of their deployment successfully.

The Fifth Fleet retired to Ulithi at the conclusion of the Okinawa strikes, arriving at the fleet anchorage on March 4. While at Ulithi, Air Group 4 departed Essex and the ship welcomed Air Group 84, the last air group to serve aboard during the war. The Marines of VMF-124 and VMF-213 had shot down 23 enemy aircraft and destroyed 64 on the ground in two months of operation. Essex’s new fighter-bomber squadron, VBF-84, inherited the Marine Corsairs. The two Marine Corsair squadrons aboard Wasp also departed, with VBF-86 assuming title to their Corsairs.

Thirty-two of 54 pilots in VBF-84 were former SB2C pilots put out of a job when VB-84 and its Helldivers was disbanded at the end of 1944.

Intrepid returned to the western Pacific after repair for the damage suffered the previous November carrying Air Group 10, the only other naval air group besides Air Group 9 to fly three tours, and the only one to fly all three tours in the Pacific. Fighting-Ten had first flown F4F Wildcats off Enterprise and at Guadalcanal in the fall of 1942, when they were led by the legendary Jimmy Flatley. They had transferred to Hellcats on return from Guadalcanal and returned to Enterprise in time to participate in the fast carrier offensive that concluded with the Marianas Turkey Shoot. Now flying the F4U-1D Corsair, they were the only Navy squadron to fly Wildcats, Hellcats and Corsairs in combat. VBF-10 was the first fighter-bomber unit to take the new 11.75-inch “tiny Tim” rocket into combat. The pilots of both squadrons were also the first to utilize G-suits since VF-8 had pioneered that equipment a year previously.

Air Group 5 also returned for a second tour, now aboard Franklin (CV-13). VF-5, VMF-214 and VMF-452 all flew Corsairs. Hancock’s new VBF-6 was also equipped with Corsairs. In all, there were now seven Navy and six Marine squadrons flying the Corsair, a remarkable turnaround in less than four months.

The fleet now prepared for participation in the looming invasion of Okinawa, set for the end of the month. Admiral Mitscher warned his captains that they could expect the largest and most sustained kamikaze attacks experienced so far, since intelligence believed the Japanese had at least 1,000 planes in Kyushu for use in such attacks. The fleet’s first mission would be to neutralize that threat as much as possible with a series of air strikes on Kyushu, the southernmost of the Home Islands.

Mitscher’s warning was prophetic. As he and his commanders met aboard Bunker Hill, Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki, now commander of the Fifth Air Fleet, bid farewell to the volunteer flight crews who were preparing to depart on a long-distance, one-way mission to attack the American fleet anchorage at Ulithi, 800 miles southeast. Ugaki, formerly chief of staff to the legendary Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto and later commander of the Center Force battleships at Leyte Gulf, had come to see the deployment of Operation Tan, a preemptive strike against Mitscher’s fast carriers.

Twenty-four P1Y1 Frances attack bombers were launched that morning. Bad weather and mechanical problems along the way reduced their number to a handful, but one Frances swept into the lagoon just after sunset. The pilot spotted Randolph, which was loading ammunition under spotlights. The call to General Quarters came just before the bomber crashed into her flight deck aft, destroying 14 aircraft and setting her ablaze. Three hours later the fires were out, but Randolph would not be part of Task Force 58 when the fleet sortied three days later.

Unbeknown to American intelligence, there were more than kamikazes waiting for them on Kyushu. The Imperial Japanese Navy Air Force was ready to deploy its newest and best fighter, flown by a unit that had among its members the best pilots the service had left. The 343rd Naval Air Group had been organized only weeks earlier by Captain Minoru Genda, perhaps Japan’s most outstanding naval aviator and one of the best Japanese naval officers of the war; he had been chosen by Admiral Yamamoto to plan the Pearl Harbor attack. With his reputation, Genda had been able to get nearly every surviving IJNAF ace assigned to the unit, including Saburo Sakai. Because of these pilots, the unit was known as “the Squadron of Experts.” They were the only unit to be completely equipped with the Kawasaki N1K2-J Shiden-Kai, a new development of the fighter American naval aviators had first met over Guam during the invasion of the Marianas and named “George.”

The N1K1-J Shiden the Americans fought over the Marianas was a land-based development of the most powerful Japanese floatplane fighter ever designed, the N1K1 Kyofu. By the time that airplane had reached production status, the nature of the war had changed so much that there was no use for it. The N1K1-J had a very similar airframe to the earlier fighter, with long stalky landing gear owing to the position of the wing.

Finally introduced into combat in the summer of 1944 following a prolonged gestation, the Shiden quickly proved itself an outstanding fighter, remaining a potent adversary to the end of the war. However, it had several shortcomings, the primary problem being the unreliability of the Homare 21 engine, Additionally, the wheel brakes were so poor that pilots often landed on the grass next to a paved runway in order to reduce the landing roll without brakes. While American Navy pilots had encountered only a few N1K1 fighters in the Marianas and the Philippines, the opinion among those who had run into it was that when there was a competent pilot in the cockpit, the George was a dangerous adversary.

The effort to put right the shortcomings of the original design led to the N1K2-J Shiden-Kai (Kai: first modification), with a nearly completely redesigned airframe. The wing position was changed from mid to low, and all 20mm cannon were housed within the wing rather than the underwing fairing, as was the outer weapon of the earlier design. Effort was also put into simplifying the airframe for ease of production; the N1J-2-J had only 43,000 parts compared with 66,000 for the N1K1-J. While the Homare 21 engine was modified, it proved no more reliable in the N1K2-J, however, and continued to create problems for pilots and maintenance crews. Excellent results were found when the prototype N1K2-J first flew on December 31, 1943. While full-scale production was set to begin in the summer of 1944, the prototypes experienced prolonged development troubles that required changes, which inexorably slowed production. Further delays came in delivery of engines, landing gear assemblies, aluminum extrusions and steel forgings as a result of the B-29 strategic bombing campaign, which came into its own in November 1944. Only 60 N1K2-Js were produced in 1944, with only 294 in 1945 by the end of the war. The “Squadron of Experts” were mounted in an airplane that equaled their enemies’, but like their German counterparts flying the Me-262 in the JV-44 “Squadron of Experts,” they would be “too little, too late.”

While Task Force 58 headed toward Japan, Hamilton McWhorter experienced the most terrifying minutes of his career as a fighter pilot.

With the Randolph having taken a kamikaze hit, while she was undergoing repairs, the squadron went ashore and was stationed at the Marine airbase on Falalop Island. We were sent out on a strike mission on Yap Island about 90 miles to the west. There was no aerial opposition, but the flak was still very intense. Just as I was recovering from a strafing run on a heavy antiaircraft gun position, I took a huge hit. I looked out and the right wing was on fire – the flames were going back past the tail! I unstrapped and opened the canopy to bale out, because I was sure the wing was going to come off immediately. Fortunately, common sense overcame the panic of the moment and I stayed with the airplane long enough to get out over the ocean, and then the fire burned itself out. I stayed unstrapped and kept the cockpit canopy open all the way back to Falalop, for fear the wing would still come off. When I got back and they checked the airplane, it turned out a flak round had hit in the right wing gunbay and set the gun charging hydraulic fluid on fire, popping all the ammo. On the terror scale of 1–10, that was about a 25.

The Fifth Fleet began its run-in to Kyushu the night of March 17. A scouting line of 12 destroyers positioned 30 miles ahead of the fleet split into two radar patrol groups to provide early warning of incoming attacks at dawn on March 18, one 30 miles west and the other 30 miles north of the launch point. Each group was covered by a CAP of eight fighters under the control of fighter direction officers aboard the destroyers. When an attack was spotted, the CAP was reinforced to 16 fighters. The first bogey appeared on the radar screens at 2145 hours on March 17; from that point the fleet was continually shadowed, though Enterprise night fighters shot down two. The destroyers also attacked two submarine contacts.

Task Force 58 was 100 miles east of the southern tip of Kyushu at 0545 hours on March 18 when the first fighter sweep was launched, composed of 32 Hellcats and Corsairs from each of the four task groups. The sweep was followed 45 minutes later by 60 Avengers and Helldivers escorted by 40 fighters from the four groups.

The Japanese were forewarned of the impending American attack and relocated many aircraft away from coastal airfields. In response, the afternoon strike targets were changed to locations further inland that were originally listed for attack on March 19. The afternoon missions made claims of 102 enemy aircraft shot down and 275 destroyed or damaged on the ground.

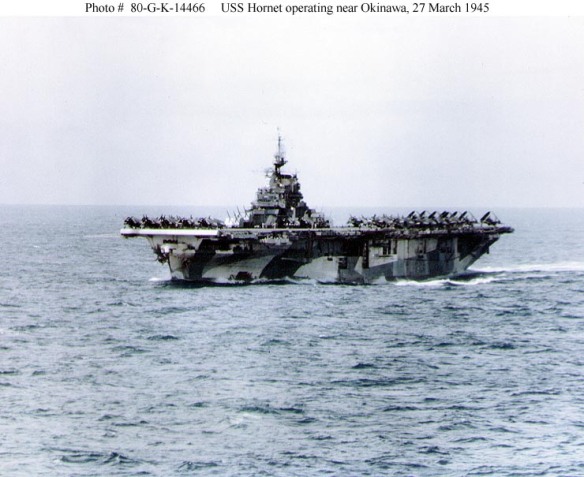

The Jolly Rogers of VF-17 had returned to combat when they came aboard Hornet at the end of January, mounted for this tour in the F6F-5 Hellcat, rather than the Corsairs they had flown the year before. Squadron commander LCDR Marshall U. Beebe, who had narrowly escaped death as commander of composite squadron VC-39 aboard the ill-fated CVE Liscombe Bay when the carrier was sunk during the Gilberts campaign, led the squadron on a sweep of Kanoya Airfield with his wingman, Lieutenant Robert C. Coats. The squadron repeatedly ran across Japanese fighter formations in the airfield vicinity, claiming a total of 32 victories. Beebe and Coats both returned to the carrier with “ace in a day” claims of five each.

Essex’s VBF-83 was the most successful Corsair squadron on March 18. In fighting over Tomioka Airfield, the Corsairs bagged 17 Zekes and a Judy, with a further nine probables. Major Hansen led four divisions of VMF-112 who ran into 20 Zekes as they headed toward Kanoya East Airfield at 19,000 feet. Five enemy fighters were shot down in the Marines’ first pass, with four more in the second. The Corsairs returned to Bennington to find none had been damaged in the fight.

Enemy attacks on the fleet were slight in terms of the number of aircraft involved, but the attacks were carried out in an aggressive and determined manner. With cloudy skies, single enemy aircraft used the cover to dodge the combat air patrols and make attacks on the fleet. While many such attackers were shot down, Yorktown and Enterprise were hit by bombs, while the recently-returned Intrepid experienced a near miss by a twin-engine plane shot down by gunfire. Yorktown’s damage was minor and the bomb that hit Enterprise failed to explode; thus all carriers continued flight operations. The problem was that little, if any, warning was being provided by radars; at times the first indication a ship was under attack was visual sighting by the close screen, with the picket destroyers providing invaluable warning with their visual sightings. The task group combat air patrols shot down a total of 12 aircraft, while shipboard antiaircraft fire got 21.

A photo reconnaissance mission flown by an F6F-5P from Bunker Hill found a large number of major Imperial Navy ships in Inland Sea harbors. Admiral Mitscher decided to attack the ships at Kure Naval Base and Kobe Harbor on March 19, while fighter sweeps flown against airfields on Shikoku and western Honshu would precede and follow the strikes to defend the fleet against attack.

A search flown by VT9N)-90 Avengers over the night of March 18–19 reported the possibility of a battleship and carrier leaving the Kure Channel, but a subsequent predawn search failed to find any ships. The first fighter sweep was launched at 0525 hours, followed an hour later by the strikes. They were about to run into an unexpected enemy.

Major Tom Mobley led 16 VMF-123 Corsairs on a dawn sweep of Kure and Hiroshima. Hearing pilots of VBF-10 calling for help, Mobley started to turn his formation when they were hit by 30 N1K2-J Shiden-Kai fighters flown by Genda’s “Squadron of Experts.” Two F4Us were shot out of the formation immediately. These Japanese pilots were vastly different from the sorry lot the Bennington Corsairs had clobbered the day before, flying two and four-plane units, using disciplined tactics and shooting accurately. The unfortunate Marines had just run into the best Japanese Navy pilots left. Outnumbered two to one, the Marines fought for their lives. Mobley shot down one enemy fighter, then took 20mm hits from a well-flown Shiden-Kai and had to pull out of the fight. He turned over command to Captain William A. Cantrel, a Solomons veteran who had shot at one Zeke over “The Slot” and missed. In two minutes over the Inland Sea, he shot down two Shidens. With his Corsair damaged and wounded in his foot, Cantrel organized a withdrawal. Eight of the Corsairs were badly shot up. During a 30-minute running fight, the aggressive Japanese hunted down cripples. Cantrel managed to hit two as he protected his charges. Finally out at sea and away from the Japanese, one Corsair gave out and the pilot parachuted near a picket destroyer. Back aboard Bennington, three of the surviving Corsairs were so badly damaged they were immediately pushed overboard. The Marines had lost six F4Us and two pilots, while they claimed nine shot down. Cantrel was awarded the Navy Cross for his leadership.

Among the 343rd pilots encountered by the Marines was Lieutenant Naoshi Kanno, who was the top-scoring Naval Academy graduate of the Pacific War. Based at Yap, Kanno first saw combat over the Marianas in June 1944, flying the N1K1-J Shiden with the original 343rd Air Group, and was credited with 30 victories that summer. While at Yap, he used the head-on attack to shoot down several Seventh Air Force B-24 Liberators. When Genda reorganized the 343rd, Kanno was named commander of the 301st Hikotai, which was the unit that initially took on the VMF-123 Corsairs during the battle of March 19. Kanno was one of the 13 unit members shot down when he was hit by a VBF-10 Corsair that came to the Marines’ rescue, though he was able to parachute safely. Kanno was credited with 13 more victories before he was killed attacking B-24s over Yaku Island on August 1,1945.

Under his command, the 301st had the highest casualties of any 343rd squadron, though it was also the top-scoring squadron.

The 343rd had received early warning of the approach of the American formations when the US planes were spotted by a C6N Myrt that managed to get the word back before it was shot down. All three squadrons took off from Kanoya Airfield. The Shidens of the 407th Hikotai were the first to encounter Americans when they came across VBF-17 Hellcats. Three aircraft were lost on both sides in the initial attack; one Hellcat and two Shidens were shot down by enemy ground fire, two fighters collided in mid-air, and one Hellcat later crashed while trying to land back aboard Hornet. In the end, the 407th Hikotai lost six fighters while shooting down eight VBF-17 Hellcats.

The Japanese had originally mistaken the VMF-123 Corsairs for Hellcats. Of the nine victories claimed by the Marines, not one was actually shot down. Kanno’s Hikotai then ran across the VBF-10 Corsairs. Two F4Us were separated and shot down, while the Americans claimed four N1K2s before they managed to escape. Hellcats of Fighting-9 shot down two Shidens when they attempted to land low on fuel. In the fighting, the 343rd Air Group claimed 52 victories, while the Americans claimed 63. Actual losses were 15 Shidens and 13 pilots, the Myrt with its three-man crew, and nine other fighters from other units. American losses were heavy: 14 fighters were shot down and seven pilots lost, in addition to 11 other aircraft shot down by the heavy flak over Kure. The difference was that the Americans would make good their losses in a week, while the 343rd did not regain full strength for six crucial weeks.

Avengers and Helldivers from Task Groups 58.3 and 58.1 concentrated on the warships at Kure, while those from Task Group 58.4 went after the ships that had been spotted at Kobe, and Task Group 58.2’s bombers concentrated on targets and installations in the Kure Naval Air Depot area. These attacks were only moderately successful, primarily owing to the extremely heavy and accurate AA fire encountered, with one group alone losing 13 aircraft over Kure. At Kure, slight damage was inflicted on the battleship Yamato, several hits were scored on the hermaphrodite battleship aircraft carrier Ise, while slight damage was inflicted on two aircraft carriers. Heavy cruiser Tone, which had last been encountered at the battle off Samar in October 1944, was set afire. The light cruiser Oyodo was severely damaged and last seen burning badly. At Kobe, what was identified as an escort carrier was hit by three 500lb bombs, and a submarine was slightly damaged.

Just after dawn on March 19, Task Group 58.2 was steaming 20 miles north of the other task groups, 50 miles off the coast of Kyushu, closer than any other unit of the fleet. Both carriers in the group had launched strikes shortly before dawn, with Franklin launching a fighter sweep to Kobe, followed 30 minutes later by a strike force of Avengers escorted by Corsairs to hit the ships in the harbor. Thirty-one Corsairs and Avengers, fully fueled and armed, were warming up on the flight deck for the next launch. The crew had been called to General Quarters 12 times in six hours over the preceding night and were already exhausted. The alert status was downgraded to Condition III by Captain Leslie E. Gehres, whose strict discipline and autocracy was disliked by many crewmen. This allowed the crew freedom to leave their GQ station to eat or sleep, while all gun crews remained at their stations. There was building cumulus in all quadrants, with 7/10 cloud layer at 2,500 feet.

At the ship’s most vulnerable moment, a D4Y Judy dive bomber suddenly popped out of the clouds directly overhead. It made a low-level run, dropping what were later identified as two 250kg bombs. The first hit the centerline of the flight deck and exploded after penetrating to the hangar deck. Sixteen of the aircraft in the hangar were fully fueled while five were partially fueled. They went up like bombs when the fire spread. Soon their guns began going off as the fire touched their ammunition. The hangar deck was devastated by the explosion of gasoline vapor. The fire spread through open hatches that allowed it to spread to the second and third decks, while the aircraft explosions shredded the flight deck overhead. It quickly spread to the Combat Information Center and Air Plot, which were knocked out. There were only two survivors of the near-instantaneous destruction.

The hangar deck explosions knocked the aircraft on the flight deck together, which caused further fires and explosions. One of the 12 “Tiny Tim” 11.75-inch air-to-surface rockets that were ignited, launched and struck a glancing blow to the island before it hit other aircraft. Franklin’s executive officer, Commander Joe Taylor, remembered that, “Each time one went off, the firefighting crews forward would instinctively hit the deck. I wish there was some way to record the name of every one of these men. Their heroism was the greatest thing I have ever seen.”

The second bomb hit aft, tearing through two decks before it exploded. Unfortunately, though the forward aviation gasoline system had been secured, aviation gas was still flowing in the aft lines. This explosion fanned the below-decks fires, triggering ammunition, bombs and rockets. Power throughout the ship was lost within minutes. The captain’s order to flood the magazines could not be carried out because the water mains had been destroyed in the explosions and fires. All shipboard communications were lost. The carrier drifted helplessly within sight of Kyushu as she took on a 13-degree starboard list.

Just before TG 58.2 commander Rear Admiral Ralph Davison left Franklin by breeches buoy to transfer his flag to Miller (DD-535), he suggested to Captain Gehres that he order the ship abandoned. Thinking of the many men still alive below decks whose escape was prevented by the fire, Gehres refused. Many had already been wounded or killed within minutes of the explosion, while others were blown overboard or forced to jump because of the fires. Surgeon LCDR George W. Fox, MD, was killed while tending the wounded and was awarded a posthumous Navy Cross. On hearing Gehres’ announcement that he was going to fight the fire, 106 officers and 604 enlisted men volunteered to stay and fight the fires with him.

Moments after the first attack, another Judy dived on Wasp. The defending gunners shot it down, though its bomb fell free and penetrated the flight deck before it exploded between the second and third decks. Fortunately, damage-control parties were able to put out the fire quickly and, within an hour, Wasp was able to resume flight operations, despite her top speed being reduced to 28 knots when a boiler room flooded and lost power.

Task Force 58 was attacked throughout the day as the enemy sent both conventional and kamikaze attacks against the fleet. Intrepid crewman Ray Stone later wrote in his diary that “the Japanese response to our raids was intense and fanatical.”

Shortly after 0800 hours, lookouts on Intrepid spotted a large twin-engine bomber low over the water and headed for the ship. 40mm battery commander Lieutenant William Lindenberger ordered his guns to open fire when the attacker was 6,000 yards distant and headed right at him. He described what happened next in his diary:

Our 5in [guns] let him have it, but he kept coming. My 40mm plus 2 two others got the range on him and set him afire at about 3000 yds. He kept coming. At 2000 yds, I saw my tracers going into him consistently, he was burning from wing tip to wingtip but he kept coming. I thought he was going to crash into us at my gun but just before he hit his right wing dipped and he paralleled the ship at 100 to 150 fleet. There was an explosion – water started raining down on us and then a thick smoke appeared. My gunner was as steady as a watchmaker during the run but afterward he shook like a leaf.

The attacker had been deflected at the last moment by the carrier’s massed antiaircraft fire. Burning debris spewed over the starboard side of the ship, damaging aircraft and starting fires on the hangar deck when it hit the water and exploded. A stray 5-inch round from Atlanta (CL-104) killed one and wounded 44 others when it hit Intrepid by mistake. The ship was fortunate that overall damage was minor with light casualties, but a shock was sent through the crew by the event that came so soon after their return to combat.

One of the heroes of the fight to save Franklin was LCDR Joseph T. O’Callahan, S.J., the ship’s Catholic chaplain. Before the war, Callahan was a Jesuit professor of mathematics and physics at Trinity College. He had reported aboard only 17 days earlier. Despite being wounded in one of the explosions, Chaplain Callahan moved through the carnage on the flight deck and administered last rites; a photograph of him engaged in this work is considered one of the iconic photos of the Pacific War. Once he was through with his religious work, he organized and directed firefighting and rescue parties. As if that were not enough, he led men below to the magazines where they retrieved hot shells and bombs that threatened to explode, bringing them to the flight deck where they were thrown overboard.

Engineering officer Lt(jg) Donald A. Gary was another of the men whose efforts were crucial in the fight. A former enlisted machinist’s mate commissioned a year previously, Gary discovered 300 men who were trapped in a blackened mess compartment filled with smoke. With no obvious way out, the men were increasingly panic-stricken from the incessant explosions. Lieutenant Gary took command and promised them they would escape. He left and groped his way through the dark, debris-filled corridors, ultimately discovering an escape route. Returning three times to the mess compartment despite menacing flames, flooding water and the possibility of additional explosions, he led men out in groups until the last was safe. That task completed, he organized fire-fighting parties to battle the hangar deck fires. He then managed to enter Fireroom No. 3, where he was able to raise steam in one boiler and restore partial power.

Chaplain O’Callahan became the only man in World War II publicly to refuse the award of the Navy Cross, on the grounds he had done only what was expected. He was awarded the Medal of Honor in February 1946 after the personal intervention of President Harry Truman, the only Navy chaplain so honored during the war. His citation reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as chaplain on board the USS Franklin when that vessel was fiercely attacked by enemy Japanese aircraft during offensive operations near Kobe, Japan, on March 19, 1945. A valiant and forceful leader, calmly braving the perilous barriers of flame and twisted metal to aid his men and his ship, Lt Comdr O’Callahan groped his way through smoke-filled corridors to the open flight deck and into the midst of violently exploding bombs, shells, rockets, and other armament. With the ship rocked by incessant explosions, with debris and fragments raining down and fires raging in ever-increasing fury, he ministered to the wounded and dying, comforting and encouraging men of all faiths; he organized and led firefighting crews into the blazing inferno on the flight deck; he directed the jettisoning of live ammunition and the flooding of the magazine; he manned a hose to cool hot, armed bombs rolling dangerously on the listing deck, continuing his efforts, despite searing, suffocating smoke which forced men to fall back gasping and imperiled others who replaced them. Serving with courage, fortitude, and deep spiritual strength, Lt Cmdr O’Callahan inspired the gallant officers and men of the Franklin to fight heroically and with profound faith in the face of almost certain death and to return their stricken ship to port.

Donald A. Gary was also awarded the Medal of Honor in the same ceremony with Chaplain O’Callahan. The guided missile frigate Gary (FFG-51) was named in his honor in 1983.

Men jumped into the sea to get away from the fires and the light cruiser Santa Fe moved in close to rescue them, then approached Franklin to take off wounded and nonessential personnel. As the cruiser came alongside to fight the fires, Franklin rolled toward her, battering her superstructure with the carrier’s imposing flight deck overhang. As the carrier went dead in the water, Captain Harold C. Fritz kept Santa Fe close alongside. Wave action clapped the two together, with the rending sound of gun sponsons crushing and antennas snapping. Aboard the destroyer Hunt (DD-674) 1,000 yards off Franklin’s beam, a signalman monitoring the carrier with his 40-power telescope was witness to a hangar deck explosion so violent it shattered parked planes and sent their engines flying through the hangar. A large group of sailors near the bow were forced back by the flames and fell off the bow “like a huge herd of cattle being shoved over a cliff,” the sailor later reported.

Survivors climbed across radio antennas from the carrier to Santa Fe and slid down lines from the flight deck to the cruiser’s forecastle.

Commander Thomas H. Morton, gunnery officer of the battleship North Carolina (BB-55) was a witness to the ship’s desperate fight for survival as the battleship maintained formation behind the burning carrier. “The Franklin was a huge mass of explosions, flames, and a tremendous column of smoke. There must have been hundreds of her crew in the water. Some had jumped, some had been blown over, and some were badly injured.”

With the fires aboard Franklin finally brought under control in the late afternoon, Pittsburgh (CA-72) moved in and a towline was rigged. Franklin’s rudder was jammed hard to starboard, which limited the towing speed to five knots. The task group moved protectively around the stricken carrier, while the other task groups launched fighter sweeps against airfields on Kyushu to disorganize any attack as the fleet withdrew slowly south. That evening an attack by eight aircraft was intercepted 80 miles out by VF(N)-90 Hellcats from Enterprise and five aircraft were shot down.

Franklin and Task Group 58.2 were 40 miles to the north of Task Force 58 at dawn on March 20, 160 miles from the nearest enemy base. Japanese snoopers finally made their appearance at 1630 hours when 15 enemy aircraft came in low and very fast as they went after the ships, splitting up for individual attacks. Wasp’s fighters shot down seven, while seven others were shot down by shipboard gunfire.

Two Judys attacked Enterprise about 1730 hours in separate attacks. The near misses caused no serious damage. Moments after the second near miss, however, two 5-inch shells fired by another ship in the formation slammed into the 40mm gun tubs forward of the bridge, killing seven and wounding 30. Spreading fires set off 20mm and 40mm shells and threatened the fueled and armed planes on the hangar deck, where eight were destroyed. Damage-control parties fought the fire for 20 minutes, at which point she came under attack a third time with another near miss off the port quarter; 15 minutes later the fires were out for good.

By the end of the day, Franklin’s repair parties had managed to unjam the rudder and work up speed to 15 knots under her own power. More snoopers appeared at sunset, however. The night fighters were unable to intercept them owing to the snoopers engaging in radical maneuvers and use of window to jam radars. At about 2300 hours, an unsuccessful eight-plane torpedo attack was made on Task Groups 58.3 and 58.1, while shadowing aircraft continued to report the fleet’s position during the night.

The next day, a large bogey was detected by radar at 1400 hours, 100 miles northwest of the fleet. Reinforcements were quickly launched and 150 fighters were soon airborne over the fleet. Thirty-two Bettys and 16 Zekes were intercepted by 24 fighters from Task Group 58.1, 50 miles distant. All were shot down for the loss of two American planes. Task Force 58 had dodged a dangerous attack; the Bettys were each carrying a small plane under their fuselage. This was the combat debut of the Thunder Corps.

Franklin was able to proceed under her own power to Pearl Harbor, where she was cleaned up and repaired sufficiently to permit her to sail under her own power through the Panama Canal and on to New York City in an epic journey of 12,000 miles. She entered the Brooklyn Navy Yard on April 28. After the end of the war, Franklin was opened to the public for Navy Day celebrations so that civilians could see first hand what the Navy had faced in the last nine and a half months of war. Film footage of Franklin’s ordeal was later woven into the 1949 feature film Task Force, with Gary Cooper in the role of Captain Gehrens.

In addition to the 807 dead, there were 487 wounded. Franklin had suffered the greatest loss of life on any Navy ship in the war after Arizona at Pearl Harbor. She survived the most severe damage experienced by any US Navy fleet carrier that did not sink. Wasp had suffered an additional 200 casualties from the attack that damaged her.

For the first time in its year-long existence, Task Force 58 had fared poorly in a sea battle. As the fleet shielded the cripples, Admiral Spruance withdrew from Japanese home waters. The invasion of Okinawa was now less than ten days away and Admiral Mitscher sensed the task force faced an intense fight.

Task Force 58 arrived off Okinawa on March 23, 1945. The final great battle of the Pacific War was about to begin.