The Battle of the Somme was the first great British attack to be made with ample supplies of guns and shells, and continued, not for days or weeks, but for months. Slowly we pressed forward to the crest of the ridges between the Somme and the Ancre, and we know from Ludendorff’s own confession that we then dealt a blow at Germany’s strength from which she never recovered. The third stage of that great battle, which won many miles of the German second position, began on July 14, 1916. The one serious check was on the right wing, where it was necessary to carry the village of Longueval and the wood called Delville in order to secure our right flank. There the South African Brigade entered for the first time into the battle-line of the West, and there they won conspicuous renown.

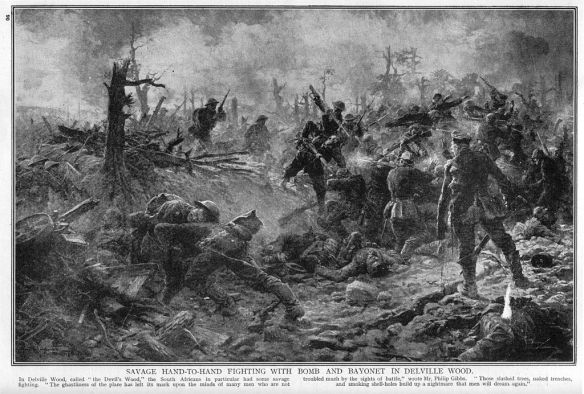

The place was the most awkward on the battle-front. It was a salient, and, therefore, the British attack was made under fire from three sides. The ground, too, was most intricate. The land sloped upwards to Longueval village, a cluster of houses among gardens and orchards around the junction of two roads. East and north-east of this hamlet stretched Delville Wood, in the shape of a blunt equilateral triangle, with an apex pointing north-westwards. The place, like most French woods, had been seamed with grassy rides, partly obscured by scrub, and along and athwart these the Germans had dug lines of trenches. The wood had been for some days a target for our guns, and was now a maze of splintered tree trunks, matted undergrowth, and shell-holes. North, north-east, and south-east, at a distance of from 50 to 200 yards from its edges, lay the main German positions, strongly protected by machine-guns. Longueval could not be firmly held unless Delville was also taken, for the northern part was commanded by the wood.

On the 14th July two Scottish brigades of the 9th Division attacked Longueval, and won most of the place; but they found that the whole village could not be held until Delville Wood was cleared. Accordingly, the South Africans – the remaining brigade of the division – were ordered to occupy the wood on the following morning. The South African Brigade, under General Lukin, had been raised a year before among the white inhabitants of South Africa. At the start about 15 per cent. were Dutch, but the proportion rose to something like 30 per cent. before the end of the campaign. Men fought in its ranks who had striven against Britain in the Boer War. Few units were better supplied with men of the right kind of experience, and none showed a better physical standard or a higher level of education and breeding.

Two hours before dawn on the 15th July the brigade advanced from Montauban towards the shadow which was Delville Wood, and the jumbled masonry, now spouting fire like a volcano, which had been Longueval. Lieutenant-Colonel Tanner of the 2nd South African Regiment was in command of the attack. By 2.40 that afternoon Tanner reported to General Lukin that he had won the whole wood with the exception of certain strong points in the north-west, abutting on Longueval and the northern orchards.

But the problem of Delville was not so much to carry the wood as to hold it. The German counter-attacks began about 3 o’clock, and the men who were holding the fringe of the wood suffered heavy casualties. As the sun went down the enemy activity increased, and their shells and liquid fire turned the darkness of night into a feverish and blazing noon , often as many as 400 shells were fired in a minute. The position that evening was that the north-west corner of the wood remained with the enemy, but that all the rest was held by South Africans strung out very thin along its edge. Twelve infantry companies, now gravely weakened, were defending a wood a little less than a square mile in area – a wood on which every German battery was accurately ranged, and which was commanded at close quarters by a semicircle of German trenches. Moreover, since the enemy had the north-west corner, he had a covered way of approach into the place.

All through the furious night of the 15th the South Africans worked for dear life at entrenchments. In that hard soil, pitted by unceasing shell-fire, and cumbered with a twisted mass of tree trunks, roots, and wire, the spade could make little way. Nevertheless, when the morning of Sunday, the 16th, dawned, a good deal of cover had been provided. At 10 a.m. an attempt was made by the South Africans and a battalion of Royal Scots to capture the northern entrance to the wood. The attempt failed, and the attacking troops had to fall back to their trenches, and for the rest of the day had to endure a steady, concentrated fire. It was hot, dusty weather, and the enemy’s curtain of shells made it almost impossible to bring up food and water or to remove the wounded. The situation was rapidly becoming desperate. Longueval and Delville had proved to be far too strongly held to be over-run at the first attack by one division. At the same time, until these were taken the object of the battle of the 14th had not been achieved, and the safety of the whole right wing of the new front was endangered. Longueval could not be won and held without Delville; Delville could not be won and held without Longueval. Fresh troops could not yet be spared to complete the work, and it must be attempted again by the same wearied and depleted battalions. What strength remained to the 9th Division must be divided between two simultaneous objectives.

That Sunday evening it was decided to make another attempt against the north-west corner. The attempt was made shortly before dawn on Monday, the 17th July, but failed. All that morning there was no change in the situation; but on the morning of Tuesday, the 18th, an attempt was made to the eastward. The Germans, however, in a counter-attack, managed to penetrate far into the southern half of the wood. The troops in Longueval had also suffered misfortunes, with the result that the enemy entered the wood on the exposed South African left.

At 2.30 that afternoon the position was very serious. Lieutenant-Colonel Thackeray, of the 3rd South African Regiment, now commanding in the wood, held no more than the south-west corner. In the other parts the garrisons had been utterly destroyed. The trenches were filled with wounded whom it was impossible to move, since most of the stretcher-bearers had themselves been killed or wounded.

That evening came the welcome news that the South Africans would be relieved at night by another brigade. But relief under such conditions was a slow and difficult business. By midnight the work had been partially carried out, and portions of the 3rd and 4th South African regiments had been withdrawn.

But as at Flodden, when

“they left the darkening heath

More desperate grew the strife of death.”

The enemy had brought up a new division, and made repeated attacks against the South African line. For two days and two nights the little remnant under Thackeray still clung to the south-west corner of the wood against impossible odds, and did not break. The German method of assault was to push forward bombers and snipers, and then to advance in mass formation from the north, north-east, and north-west simultaneously.

Three attacks on the night of Tuesday, the 18th, were repelled with heavy losses to the enemy; but in the last of them the South Africans were assaulted on three sides. All through Wednesday, the 19th, the gallant handful suffered incessant shelling and sniping, the latter now from very close. It was the same on Thursday, the 20th; but still relief tarried. At last, at 6 o’clock that evening, troops of a fresh division were able to take over what was left to us of Longueval and the little segment of Delville Wood. Thackeray marched out with two officers, both wounded, and 140 other ranks, gathered from all the regiments of the South African Brigade.

The six days and five nights during which the South African Brigade held the most difficult post on the British front – a corner of death on which the enemy fire was concentrated from three sides at all hours, and into which fresh German troops, vastly superior in numbers, made periodic incursions, only to be broken and driven back – constituted an epoch of terror and glory scarcely equalled in the campaign. There were other positions as difficult, but they were not held so long; there were cases of as protracted a defence, but the assault was not so violent and continuous.

Let us measure it by the stern test of losses. At midnight on the 14th July, when Lukin received his orders, the brigade numbered 121 officers and 3,032 men. When Thackeray marched out on the 20th he had a remnant of 143, and the total ultimately assembled was about 750. Of the officers, 23 were killed or died of wounds, 47 were wounded, and 15 were missing. But the price was not paid in vain. The brigade did what it was ordered to do, and did not yield until it was withdrawn.

There is no more solemn moment in war than the parade of men after a battle. The few hundred haggard survivors in the bright sunshine behind the lines were too weary and broken to realize how great a thing they had done. Sir Douglas Haig sent his congratulations. The Commander of the Fourth Army, Sir Henry Rawlinson, wrote that “In the capture of Delville Wood the gallantry, perseverance, and determination of the South African Brigade deserves the highest commendation.” They had earned the praise of their own intrepid commanding officers, who had gone through the worst side by side with their men. “Each individual,” said Tanner’s report, “was firm in the knowledge of his confidence in his comrades, and was, therefore, able to fight with that power which good discipline alone can produce. A finer record of this spirit could not be found than the line of silent bodies along the Strand (the name of one of the rides in the wood), over which the enemy had not dared to tread.” But the most impressive tribute was that of their Brigadier. When the remnant of his brigade paraded before him, Lukin took the salute with uncovered head and eyes not free from tears.