‘War is a contest between two human intelligences rather than between two bodies of armed men.’

Lecture at British Staff College, 1901

German East Africa wasn’t much of a country, Tanga wasn’t much of a town, and Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck’s 800 Askaris weren’t much of an army. Yet it was here that the initial battle in Africa’s share of the First World War took place.

To the 8,000 Indian soldiers of Major General Aitken this action came as a total surprise. Not so to the German garrison. For weeks they had been forewarned by letters written by German sympathisers in India and arriving by regular mailboat. They revealed that an Indian contingent of the British Army was embarking at Bombay, and that their officers had labelled their private luggage with: ‘Indian Expeditionary Force “B”, Mombassa, East Africa.’ Though supposedly a secret mission, both the British and the German press, had described in great detail this forthcoming invasion.

Since the main port in German East Africa, Dar es Salaam, had been blocked by sinking an old ship across the harbour entrance, there were only two viable sea ports the English could attack. The Deutsche Schutzstaffel was strategically encamped between the two places, Lindi and Tanga.

At the outbreak of the First World War, the British Army was hard pressed by the lightning advance of German forces into France. Therefore, any challenge Germany could put up in Africa to the world’s number one coloniser, the British Empire, was viewed as of only secondary importance. The task to conquer German East Africa was allotted to a low-grade unit of the Indian Army, with soldiers so untrained that most had never fired a rifle before. To put such an outfit under the command of an incompetent leader was asking for trouble. Major General Aitken was a man of unwavering confidence in his own ability. Thirty years of colonial service in India had convinced him that the forthcoming campaign in East Africa would be a walkover against a ‘bunch of barefoot blacks led by ignorant Huns’. In the face of his fixed bayonets they would lay down their weapons and put up their arms. Then he would round them up, lock them up and be home by Christmas 1914.

His force of 8,000 foot soldiers was a ramshackle outfit pulled together at the last moment. They spoke twelve different languages, were of six different faiths, and were led by British officers who had never set eyes on their troops before they embarked, they didn’t speak their language, and had never been to Africa before. That included the general. When Aitken received his orders, he immediately loaded his troops aboard several steamships. Bad weather prevented them from sailing for sixteen days, yet he insisted that his forces remained aboard, jammed between decks in hot cubicles. They suffered seasickness and diarrhoea from the storm, which added little to their fighting spirit. Discipline broke down, they quarrelled and fought with each other. Even Aitken’s own intelligence officer, Captain Meinertzhagen, referred to them as ‘the worst in India’. In one of his letters home he wrote: ‘I tremble to think what may happen when we meet up with serious opposition.’ That was about to happen.

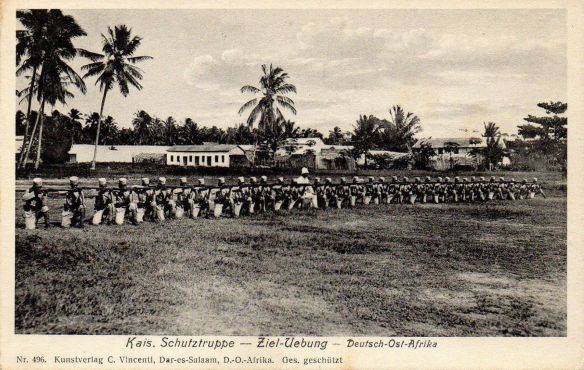

Aitken’s bad luck was to run into one of the most brilliant tacticians of the First World War, Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck. With only a handful of German instructors by his side, recruited from a stranded German cruiser, he had trained a thousand local auxiliaries, or Askaris, who had been signed up from the fiercest war tribes of the region. These wild warriors he turned into a well-drilled and well-co-ordinated hit-and-run force; he taught them to adapt to the enemy, to take cover and to exploit any opening by laying an ambush. Their passing-out test was to hit a target from 500 metres. On top of this, they were familiar with snakes, lions and scorpions and knew every foot of their homeland, while the English didn’t have maps other than pages torn from a school atlas.

General Aitken never understood that flexibility was needed and that fighting conditions in the African bush differed from those on the Indian subcontinent. He wasn’t the only one who had failed to learn the lesson from recent colonial wars in Africa, where the machine gun proved its value as a highly cost-effective weapon. Its operation took but a handful of white men to inflict maximum damage to the grouped attacker. In the Indian Army, such a weapon was considered too expensive, used up too much ammunition and invited a defensive spirit in the troop.

Tanga was a quaint little harbour along the East African Coast, with low wooden houses, neatly painted white, with well-kept gardens in front. With Teutonic efficiency, colonial officials had turned Tanga into a copy of a Prussian town on the Baltic. In front of the city hall, like everything else painted in brilliant white, stood a tall flagpole, where the Imperial German flag of black, white and red was hoisted every morning by a detachment of the local Askaris. Herr Auracher, the mayor of Tanga, ran the town ran like a Swiss watch and made sure that the good citizens observed Prussian civic virtues. All lived a quiet, colonial existence. His boss, Governor Baron von Schnee, had done a splendid job of keeping peace with the warrior tribes of the interior by distributing glass beads and framed prints of his Emperor to tribal chieftains.

The stillness of this harbour must have come as a pleasant surprise to Captain F. W. Caufield of the cruiser H.M.S. Fox that 2 November 1914, when he showed up with his convoy outside Tanga. There was no sign of hostility, not even the Imperial German flag was flying. That was always a good sign with those nationalistic Huns, he thought. Captain Caufield had himself rowed to the quay where Herr Auracher, resplendent in a sparkling white, starched collar shirt, with dark tie and pith helmet, courteously awaited his arrival and made his excuses for Governor von Schnee, who was ‘away on an inspection tour’.

‘Herr Burgomaster, in the name of His Majesty you are informed that any truce previously concluded between our two countries is hereby suspended.’

The man didn’t seem ruffled by the news as he bowed slightly. ‘Herr Kapitän, you will certainly allow me time to consult with my higher authorities.’

‘Please do’, replied the captain pleasantly. There was no sense rushing things; in any case, he needed confirmation of a disturbing rumour. The German cruiser SMS Königsberg, registered in British naval books as a mine layer, had been recently reported in these waters.

‘But, tell me, my good man, is the harbour mined?’ asked Caufield.

Auracher threw furtive glances at the cruiser hovering outside the harbour entrance, its heavy guns pointing straight at his wooden city hall.

‘Of course, Herr Kapitän, such is standard practice in the German military manual.’ With which the Burgomaster begged to be excused and disappeared. His ‘consultation with higher authorities’ consisted of forwarding an urgent message to Colonel von Lettow-Vorbeck that the Indian Expeditionary Force ‘B’ had arrived at his little town. The German commander immediately rushed his two available companies into previously established strong points, while Herr Auracher took off his pith helmet, changed into his German Army uniform and, in a final gesture of defiance, hoisted the Imperial flag.

Meanwhile, Captain Caufield had ordered his sailors of the Fox to sweep for mines. Of course they never found mines. But they took their time, since it was a very hot day, while the rest of General Aitken’s invasion fleet was sweltering in the equatorial heat on an oily ocean. The British general was highly upset over the delay. While his sailors were still rowing aimlessly around the harbour, Captain Caufield convinced General Aitken not to risk losing a ship to a mine but instead to disembark the invasion force about a mile further down the coast. Their new landing place proved to be an almost impenetrable mangrove swamp, infested with mosquitoes and poisonous snakes. This they didn’t discover until the first troops had set foot ashore, which was well after darkness. As the Indians had never been outside their own villages, and rumours had circulated aboard the troopships about the horrors of cannibalism in Africa and the cruelty of the Germans, their nerves were frayed and they expected to find an enemy behind every tree. They shot at passing shadows, which happened to be their own unfortunate comrades.

In the first morning light the unsuitability of the landing site became obvious; rather than changing it, General Aitken, eager to terminate his African campaign before Christmas, ordered all supplies to be brought ashore. There were motorcycles and wireless sets, boxes of corned beef and shells. And, not to be outdone by their leader, every officer had brought along his parade uniform for the forthcoming victory pageant, adding their personal luggage to the piles of crates and boxes. All this back-and-forth manoeuvring, which could only be accomplished by rowing-boat across the treacherous coral reefs, took two days, which allowed the Germans ample time to further fortify their positions.

Contrary to the British general, who didn’t believe in reconnaissance, Lettow-Vorbeck sent one of his officers to take a closer look. The man, a Berliner thinly disguised as an Arab fisherman, reported back that the invasion beachhead looked like ‘a Sunday along the Rhine’, of picnics and bathers.

For forty-eight hours, Brigadier Tighe, feeling elated that he had managed to get his brigade safely ashore, stalled by telling his commander that the men were too exhausted to ‘give it a decent go’ and assault the town. Even when an enterprising Arab trader, who had arrived by boat to peddle his wares to the troops, informed one of Aitken’s staff officers that there were almost no Germans in the sector, the general still declined to issue the order for attack. Time was frittered away by a general who couldn’t make up his mind. Meanwhile, the Germans had managed to rush in two additional Askari companies to back up their handful of defenders.

On 4 November 1914 came General Aitken’s order to ‘advance and attack’, and that without prior scouting. Any commander who fails to explore a hostile territory and allows the enemy the element of surprise invites disaster. The sepoys of the 63rd Palmacotta Light Infantry, the 61st Pioneers and the 13th Rajputs were ordered to fix bayonets and form into line of battle about a thousand yards wide, which was impossible, given that they had to cross a mangrove swamp in knee-deep water and mud, threading their way through a tangle of tree trunks and mangrove roots. Led by Brigadier Tighe, the troops of his Bangalore Brigade advanced but couldn’t spot any Germans.

‘Curse it, the Boche has run’, stated a young British lieutenant, disappointed at having been deprived of his moment of glory. Together with two other company commanders, he climbed up a kopie to have a better view. The three raised their heads – and fell down dead. A bugle sounded, a row of German Askaris popped up from the waters of the swamp like shiny black ghosts and rushed at the hapless Bangalores with a bloodcurdling yell. This so panicked the sepoys that they threw away their rifles and ran, leaving behind their dozen officers to be cut down by the pangas of the Askaris. Captain Meinertzhagen of the Rajputs tried to put a halt to the panic which got so bad, that, when one of the Indian officers tried to force his way past him by drawing his sword, Meinertzhagen had to shoot him.

Brigadier Tighe signalled to the ships that he was coming under attack by 2–3,000 Germans, when in fact the whole Askari force was only two hundred and fifty and the attack had been carried out by less than two companies, the 7th and 8th Schutztruppe. This initial, futile attempt had cost the British over 300 casualties; the rest of the troops had run all the way back to the beach and many were now up to their necks in water, screaming for help.

5 November. General Aitken was so furious over the Bangalores’ unmilitary behaviour, and the thrashing his units had received, that he ordered all his remaining reserves onto the beach to be thrown at Lettow-Vorbeck, and that again without sending out scout patrols. He showed his ineptness by mixing his weakest units with his two first-rate formations, the North Lancashire Regiment and the Gurkhas of the Kashmiri Rifles.

‘We’ll do it with cold steel’, was Aitken’s response to the offer of a nourished naval bombardment by H.M.S. Fox. Again, the unit commanders were given the order to advance with fixed bayonets. By now, the beach was piled so high with supplies that the freshly disembarking troops had to clamber over cases and fight their way through bug-eyed sepoys to get into a semblance of order for the advance on an enemy who, once again, had mysteriously disappeared into the swamp.

Three hundred metres outside of the town, along a narrow earthen dam put there years before to protect the town from the encroaching swamp, Lettow-Vorbeck had put up a formidable line of dug-in defences, occupied by the 4th, 7th, 8th and 13th Schutztruppe. All his units lay beautifully camouflaged behind rows of bamboo which surrounded the swamp; every company was linked to his command post by field telephones. Barbed-wire entanglements, concealed with leaves and swamp flowers, fronted strong points manned with machine guns. It would be a suicidal mission to rush such defences with ‘cold steel’. In fact, the German commander did not have to organise the ambush, the Indian Imperial Service Brigade simply stumbled into it. To begin with, the sepoys slugged their way through mud and stumbled over submerged mangrove roots, suffering badly from thirst and heat, while Askari snipers, planted in the crowns of bao-bab trees, picked off their brightly sashed, pith-helmeted officers. Then the Germans kept up a galling machine-gun fire which soon showed its effectiveness. It punched great gaps into the various units. Everything was going just as Lettow-Vorbeck had planned. A ragged line of Indians began to stumble around in the bog, firing wildly into the leaves ahead and, more than once, shooting down their comrades in front. With the vanguard in full retreat, and the rear still advancing, this created a bunched-up mass of confused soldiery which offered an ideal target for the German machine-gunners. Only the North Lancashires and Gurkhas managed to advance with great courage and, after a fierce hand-to-hand fight, took the local customs house. From there they rushed into the town where they reached the Hotel Deutscher Kaiser. They pulled down the German Tricolor and raised instead the Union Jack, an event observed with a great cheer from the ships standing off at sea.

For Lettow Vorbeck, assisted by his two ADC’s, Major Von Prinz and Major Kraut, the situation became serious. The British crack troops had broken into town, and, unless they were stopped, the door to the colony would be wide open. Under the onslaught of the wicked curved knives of the Gurkhas some of the inexperienced young Askaris had faltered and were hiding out in buildings. It took a bold step to get them back in line. Lettow-Vorbeck, the Prussian junker, faced them down: ‘Do I see women, or the proud warrior sons of the Wahehe and Angoni?’ But they wouldn’t move, until something else happened.

When one of the Wahehe Askaris jumped up and tried to dash off, Captain von Hammerstein, a company commander, took a half-filled bottle of wine from his map case and hurled it after the fleeing man. It struck him on the woolly head and he fell to the ground, to the howling laughter of the Angoni. That did it. The Wahehe tribesmen, furious over the cowardly behaviour of one of their tribe in front of the Angonis, kicked the shit out of him, then picked up their heavy Mauser rifles, and with a scream of ‘Wahindi ni wadudu’, raced after Major von Prinz. They were followed by the equally eager Angoni tribesmen, yelling their own terrible native war cry. With blazing rifles and machine guns placed on the shoulders of others to steady their aim, they ran through the town and threw out the Gurkhas. Then they lashed into the open flank of the British force in the swamp. A mêlée of pangas against kukris (Gurkha knives) soon turned into a bloody massacre. Major von Prinz was killed, while on the other side, the 101st Bombay Grenadier battalion was mowed down in a hail of bullets from German machine guns and Askari swords and ceased to exist as a fighting force. But due to the headlong rush by his Wahehes and Angonis of the 4th and 13th companies, Lettow-Vorbeck’s left flank was now dangerously exposed and threatened by the Lancashire men in and around the customs house.

Contrary to his German opponent who directed the battle from his own trenchline and thus could take advantage of every opportunity, the British general, who had remained aboard his headquarters ship, couldn’t see what was going on, since his view was obstructed by the dense jungle. A message from the commander of the North Lancs was received by General Aitken. It gave the precise position of the enemy’s deadly machine guns and asked for artillery support to soften up the German line before an attack on the Germans could be launched. But General Aitken was frozen into inactivity and no naval bombardment was ordered. To keep down their casualties, it left the North Lancs with no other choice than to pepper the bamboo growth with their Maxim guns – to little effect since the Germans and their Askaris were well down in their holes. But the gunfire did keep the Germans’ heads down and their devastatingly accurate rifle fire ceased. The British commanders didn’t realise that the Askaris had almost run out of bullets and were getting ready to stage a desperate, final bayonet charge.

If ever there was a moment for a decisive British victory, this was it. But something most unexpected came to the assistance of the Germans. The swamp was ringed by dead trees. Like some petrified forest, their grey, barren branches reached for the sky. Attached to these branches, drooping like giant bats, were cigar-shaped woven baskets which the natives used to contain massive hives of African bees, terribly aggressive and astounding in size. Their honey had always been a source of great delicacy for the locals who knew how to protect themselves against the vicious stings by applying thick layers of grease over arms and faces.

But now, the noise from the continuous firing must have upset their tranquil occupation of producing honey, or perhaps the hail of bullets had split open the baskets and shattered their hives – whatever the reason, dense swarms of humming, stinging beasties emerged from the hives and rose in dense clouds around the treetops before they attacked the advancing and unprotected British contingent. They stung and stung and then stung some more. Panic spread; the Indians turned and ran, hotly pursued by dense clouds of angry bees. One may well imagine the spectacle this presented to General Aitken, still aboard his HQ ship, when hundreds of wildly gesticulating soldiers minus their rifles, their arms waving like windmills, emerged from the mangroves and plunged headlong into the ocean. Because there was no more shooting, but only pained screams from the fleeing foot soldiers, a staff officer remarked: ‘My God, General, our men are driven back again. What devilish feat have the Germans been up to?’

The explanation was quite simple: hell hath no fury like an angry bee. Why did the insects attack only the Indian Army units? Perhaps it had to do with body odour, the same way that dogs can smell fear. A British signalman was awarded the Military Cross because he kept on sending his signal while being stung by 300 bees. It was the first time in history a medal was given for bravery under aerial attack.

Aitken was livid over his troops’ cowardice and finally ordered a naval bombardment of Tanga. The first shell hit the local hospital, jammed with British casualties. Most of the other shells fell on his own troops, now in full retreat. When the remaining North Lancs finally reached shore, a sergeant from Manchester remarked drily: ‘I dun mind the bloody Hun shoot’n at me, but bees stingin’ my arse, that’s a bit ’ard to take.’

When quiet settled over the field of battle and the bees had once again retreated into their hives, the count of dead or wounded Germans was 70, 15 Europeans and 54 Askaris, while the British left behind 800 dead and an equal number of wounded and missing, probably drowned without trace in the swamp. The beaten British armada upped anchor and returned to Mombasa, where – as the final insult – the local British colonial customs inspector refused General Aitken’s flotilla entry into the harbour for having failed to pay the 5 per cent ad valorem tax.

In England the outcome of the first battle in Africa was received with shock. How could a handful of black auxiliaries lead the British expeditionary force to such ignominious defeat? An excuse had to be found, and The Times went so far as to accuse Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck of having employed a new, tactical battlefield weapon: swarms of trained warrior bees. Nobody dared to admit that General Aitken was the wrong man to send into a theatre of war he hadn’t begun to understand. His Napoleonic idea of ‘advance and attack’ with fixed bayonets was a thing of the past. By August 1914, Allied commanders had discovered that such tactics no longer worked on the Western Front and they certainly would not work in Africa. It was sheer lunacy to launch a human wave attack against well-trained tribesmen, sitting in the bush armed with machine guns, in a landscape where tacticians like the Boers and Lettow-Vorbeck had rewritten the book on colonial warfare – although, in later years, the German colonel never forgot to give praise to his auxiliaries, the bees.

With a force of only 155 German officers and soldiers, 1,200 African Askaris, plus 3,000 porters, Major General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck’s masterly conducted operations held down 120,000 British colonial troops under the South African generals Smuts and Van Deventer. The Askari force fought on to the last day of the war and only surrendered on Armistice Day, of 1918.

As for the Battle of the Bees, the equipment left behind by the British on the beach at Tanga allowed Lettow-Vorbeck to form new regiments, arm them with modern British weapons and continue the fight for four more years.

Colonel von Lettow-Vorbeck was promoted to major general. Major General Aitken was cashiered and reduced to colonel.

What if – General Aitken’s expedition had been successful?

German East Africa would have become British Tanganyika (today’s Tanzania), and the World War, African segment, finished in 1914.