Although aeroplanes flying overhead had become commonplace, it was crashes that still captured the public’s attention. That summer, however, only one accident on July 20 caught the eye of the local press. The flight of what may well have been an FE2b of 51 Squadron, from Thetford or Tydd St Mary, was interrupted when its engine stopped suddenly over Holbeach Marsh and began to emit smoke. Gliding to earth at once, the pilot landed at Leadenhall Farm. Unfortunately potato ridges, onto which he alighted, are not conducive to safe landings and the aeroplane overturned. The pilot was unhurt, but his observer sustained a few cuts in the process.

After this lull, eight German Naval Zeppelins reopened the night battle by attempting another attack on London on July 31. It was yet another failure. Adverse winds over the North Sea completely scattered the force and airships were seen as far apart as Kent and Skegness. Fog inland also added to their problems but it was equally unhelpful to the defenders and the airships kept coming during that murky Fenland night. From landfall at Skegness L16 (Kptlt Erich Summerfeldt) crossed the north of the region and penetrated unchallenged as far as Newark, while L14 (Hauptmann Kuno Manger) flew around the March area. All bombs dropped, believed to total about thirty-two in number, fell in open countryside. The only casualties reported were two cows!

It was September 1916 before the fledgling night defences began to turn the tide. Airship SL11, a wooden-framework design built by the Schutte-Lanz airship manufacturing company and operated by the German Army, was destroyed on the night of September 2/3, by Lt Leefe Robinson, falling at Cuffley to the north of London. His success, in shooting down the first airship to be brought down on British soil, marked a significant upturn in fortune for the Home Defences.

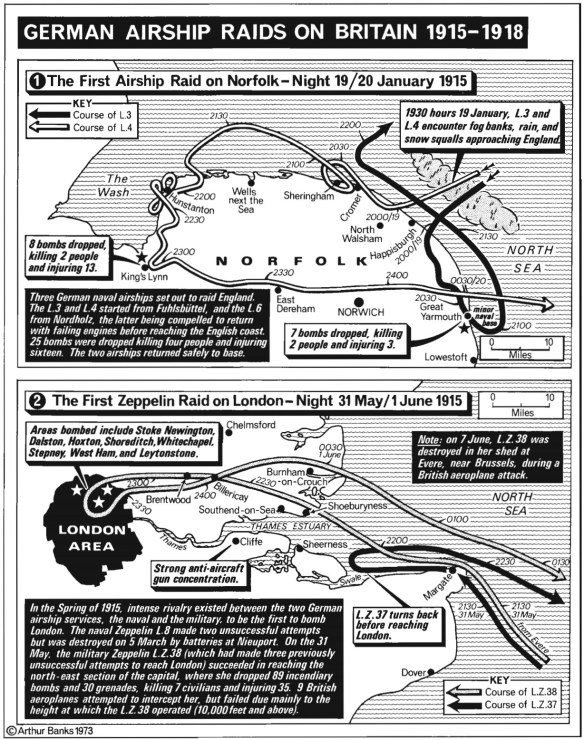

On this momentous night, the greatest airship fleet ever assembled concentrated over East Anglia to mount an attack on London. Once more, though, it failed in its primary objective. Official records show that although many bombs were dropped by the fifteen airships most of these fell harmlessly in open countryside. Poor weather, strong winds, heavy rain and icing were factors chiefly responsible for the failure. It was 22.00 when Naval Zeppelin L14 (Hptmn Kuno Manger) was recorded passing Wells-next-the-sea. Manger swung south over The Wash, near Hunstanton, heading for King’s Lynn, which he circled an hour later. Reaching Downham Market by midnight L14 left the region south of Upwood and proceeded to undertake a grand tour of the Cambridgeshire, Essex and Suffolk countryside, scattering bombs as it tracked north to exit the coast at Mundesley after seven hours over British territory.

During the remainder of 1916 five more airships were destroyed over England. Apart from the natural dangers of adverse winds and bad weather, there had been little for the Zeppelins to fear from anti-aircraft (AA) gunfire or fighters in the early war years. Natural hazards were an ever-present danger but analysis of the airship fleet’s performance told the War Office that enemy airships were still only operating at altitudes of 8,000 to 10,000 feet. At these heights it should be vulnerable to AA fire, searchlights and more significantly to fighters, if only the performance and disposition of all these components could be improved.

From mid 1916 this improvement had begun to materialise. In particular, fighter aeroplane design and performance was showing noticeable, if modest, changes. Another much more significant change, however, was the introduction of explosive/incendiary machine-gun ammunition, like the Brock or Pomeroy types, and incendiary ammunition such as the Buckingham or SPK types, with which fighters could now attack these potentially highly inflammable raiders. It was well understood that the hydrogen gas that filled the Zeppelins was inflammable but it needed to mix with oxygen to create that unstable state. Ordinary ball (solid) ammunition simply punched holes in the gas cells – allowing gas to escape and mix with ambient air – but there was nothing to ignite the mixture at the point of impact, where it would be at its most concentrated. Aircraft machine guns were now generally loaded with a blend of explosive and incendiary rounds and this was found to be a lethal combination. All that remained was to catch the blighters!

It was on the night of September 23/24 that explosions next rocked Fenland soil. Naval Zeppelin L13 (Kptlt Franz Georg Eichler) was one of twelve airships that crossed the English coast between The Wash and the Thames, seeking London and targets in the Midlands. Part of the London force comprised four new ‘Super’ class airships (L30/31/32/33). Measuring 640 feet in length and carried aloft by almost two million cubic feet of hydrogen gas, two of these giants were to meet a fiery end that night, proving the lethal effectiveness of the new incendiary ammunition. Meanwhile, back in rural Lincolnshire the calm of the night was being shattered too.

Interviewed in 1990, Cecil Haresign, farmer and lifelong resident of Surfleet Fen, near Spalding, recalled that night, seventy-four years earlier. His memory was crystal clear as the raid he said, “… was two days before the annual Spalding Horse Fair.” This coincided with the date of the raid September 23/24 1916 and the track of L13. “Aeroplanes,” he recalled, “had been using George Mowbray’s field as a landing ground for some time.” These are believed to have been from 38 Squadron, as mentioned earlier. “Often as many as nine machines could be counted at one time in the field, the centre of which was marked by a chalk circle about forty feet in diameter.”

Mr Haresign and others were of the opinion that the field had a dual purpose of also acting as a decoy for Zeppelin bombs. During most days sheep were allowed to graze the field but a large pen was staked out into which they could be herded, presumably to allow aeroplanes to land by day or night. A small contingent of soldiers was housed in a hut in one corner of the field. In addition to being shepherds it was their task to set out a flare-path of oil pans, lit to give off a smoky, yellow glare at night. Although to the locals it may have seemed like a decoy device, in the circumstances it was probably a night as well as a day landing ground for the RFC. Popularity for the decoy theory would, no doubt, be gained when, on the night of September 23/24, the oil lamps were lit and apparently promptly attracted a rain of bombs as an airship slowly circled the village. Five bombs showered down at intervals, falling at Grange Farm (failed to explode), allotments near Second Drove (house tiles damaged), near the main Gosberton to Dowsby road at Fourth Drove, and on the bank of the Forty Foot river. Next morning a somewhat shaken Private Albert Foulsham, one of the airfield contingent, had quite a tale to tell curious villagers. This dour Yorkshireman, out lighting oil lamps for the airfield flare-path, received the fright of his life when a loud whistling noise was terminated by a huge ‘crump’, which threw him to the ground and showered him with earth. The fifth bomb had gouged a large crater in the middle of his flare-path. Some accounts claim L13 was attacked that night by a 38 Squadron BE2c near Sleaford but this is unsubstantiated.

It was now autumn. Bad weather, fog and icing conditions conspired against the German airship force sent out on October 1/2 1916, once more targeting London and the Midlands. With losses now occurring on almost every raid it must have become apparent to these crews that the defences were getting the measure of the attackers. For their persistence under such difficult flying conditions, they are to be admired for the same qualities that WW2 aircrews displayed at night on both sides, knowing the odds were shortening with every sortie.

Seven Zeppelins made landfall on the Norfolk and Lincolnshire coasts either side of The Wash. Kptlt Mathy in L31 headed directly for London but met a fiery end over Potters Bar at the hands of 2/Lt W J Tempest. Of the other six airships, L14, L21 and Super class L34 all passed over the Fens, with L14 being chased around the Sleaford area, unsuccessfully, by a BE12 from 38 Squadron at Leadenham. This latter incident may well have been that which was confused with the previous raid. L34 tracked in from Cromer to Oundle and Corby, where coming under AA fire, Kplt Dietrich released seventeen HE bombs before heading for the Lincolnshire coast via Stamford.

Almost two months elapsed before the German Navy sent out another airship raid when ten Zeppelins left the Heligoland area on the night of November 27/28 1916, bound for Midland targets. This raid conformed to much the same pattern as its predecessors, with the raiders becoming dispersed, lost and generally off target. Furthermore, the defenders mounted a record level of sorties and enjoyed considerable success. Zeppelin L21 (Oblt-z-See Kurt Frankenberg), setting out from Nordholz, came in over the Yorkshire coast heading for Midland targets. In this respect Frankenberg appears to have been the most successful of his group. He tracked via Leeds and Sheffield to the Potteries (Birmingham) area which was bombed but with no serious effect. It was L21’s homeward track, however, that led it into deep trouble.

Leading a charmed life, for a while Kurt Frankenberg steered L21 through the night sky above a string of RFC airfields. Turning east after his bombs were released, he passed south of Nottingham towards the Fens north of Peterborough. Entering 38 Squadron territory L21 flew perilously close to Buckminster, Leadenham and Stamford airfields then on into 51 Squadron’s patch, as it headed for the Norfolk coast and home. First, 38 Squadron sent up five aeroplanes in pursuit, one of which, a BE2e flown by Capt G Birley, made contact with L21 east of Buckminster. After a long chase into the Fens, Birley had climbed to 11,000 feet before catching up with the airship. He fired off a full drum of ammunition at the target without any visible effect. The Zeppelin was by no means a sitting duck, for it appeared to manoeuvre continually, giving the impression of trying to avoid its attacker.

Eventually Birley lost sight of L21 but the chase was taken up by Second Lieutenant D Allan in a BE2e from Leadenham. Flying now in the general direction of Spalding at 12,000 feet altitude and with the ‘Zepp’ nearly 2,000 feet above him, the poor old BE2’s performance was quite inadequate to allow Allan even to keep pace and he, too, lost his quarry. As L21 cruised high above the dark fenscape no other contacts were reported until it left the region. Then, forewarned, 51 Squadron put up an FE2b from Marham but the pilot, Lt Gayner, having struggled to come within sight of his target, was forced to land with engine trouble. The lucky (so far) L21 crossed the coast near Great Yarmouth where two BE2c aircraft from RNAS Great Yarmouth finally caught up with her in the cold light of dawn and this time there was to be no mistake. Flight Lieutenant Egbert Cadbury and Flight Sub-Lt Edward Pulling were jointly credited with shooting down L21, which crashed into the sea in flames, with the loss of all hands.

New Year 1917 brought a further slight change in air defence policy. The War Office believed the night Zeppelin menace and day bomber offensive (the latter mostly directed against south-east England) was, in the light of 1916’s successes, now contained. Thoughts were therefore refocused on France and as a result 51 Squadron, for example, lost some of its FE2bs to help form the nucleus of a new night bomber squadron in France. There were even cuts in the home AA gun strength.

On the German side, leader of the airship fleet, Peter Strasser, was severely shaken by the reverses his airships had suffered, but he seemed determined to carry on the battle despite the mounting odds and convinced his masters to back him. As mentioned earlier, airship operating altitudes were generally up to 10-12,000 feet and British Home Defence fighters, although clearly stretched to reach that level, were achieving results. In addition AA guns, working in conjunction with searchlights, were also taking their toll. In an effort to avoid interception German strategy also took a new turn. A programme was begun in which new airships (called ‘heightclimbers’) were built and stripped of all excess weight to maximise their higher-flying capabilities. This new class of Zeppelin included L35, L36, L39, L40, L41, L42 and L47, which could now reach altitudes of between 16,000 and 20,000 feet. High-flying Zeppelin raids of early 1917 thus proved to be well beyond the altitude capability of most of the defending fighters. However, in other respects, the new class of airship suffered even more from weather-related problems, particularly the greater effects of adverse winds at the higher altitudes flown. Navigation, therefore, suffered and as a consequence bombing results were still generally ineffective.

The New Year also brought a substantial drop in the number of airship raids mounted against England, with only seven during the whole year compared to twenty-two in 1916 and twenty in 1915. Defences were just too good, and the Germans were bloodied. Apart from one unconfirmed report of a Zeppelin being seen near The Wash on September 24/25, it was not until October 19/20 1917, a full year since the last major incursion into the region’s airspace, that Zeppelins returned in earnest – but yet again with poor results. This was the occasion of an attack, intended for the north of England, which subsequently became known as ‘the Silent Raid’. Eleven airships set off for England, but encountering strong north winds at altitudes up to 20,000 feet they became lost and widely dispersed even before they crossed the English coast. Crews also suffered much discomfort from lack of oxygen and the biting, -30°F, cold. These undoubtedly brave men must have wondered if it was all really worth the effort, but discipline and leadership prevailed.

Boston came in for unusual attention as it was overflown by no less than four of these Naval Zeppelins, L44 (Kptlt Franz Stabbert), L47 (Kptlt Max von Freudenreich), L52 (Oblt-z-See Kurt Friemel) and L55 (Kptlt Hans-Kurt Flemming). Apparently, though, no bombs were dropped, probably due to dense cloud and fog obscuring the town itself. It was this same cloud layer which deadened engine sounds to those below, giving rise to the erroneous notion that engines were shut down to coast in silently – hence ‘the Silent Raid’. Tracking down The Wash, L44 flew up the Witham Haven river before turning south to pick up the railway line to Spalding and Peterborough, on its way to Bedford, which was bombed. Cruising across the northern Home Counties, it left British territory behind at Folkestone, having dropped other bombs at intervals on the way. L47 crossed the Lincolnshire coast near Sutton-on-Sea, spotted Skegness on which it dropped one bomb, before making off for Boston. This airship also crossed Witham Haven, then the mouth of the Welland river but, thereafter, seemed to wander aimlessly, first in the direction of Holbeach, then back to Spalding and on to Stamford. Reaching the latter, L47 appeared to regain its bearings, setting a steady course to the village of Holme, near Peterborough (bombed), before leaving the Fens at Ramsey (bombed), en route to Ipswich and Harwich. Oberleutnant-zur-See Friemel, in L52, followed closely the route of L47, but identifying his own location from the Welland river and Witham river estuaries, he struck inland to attack Northampton. This Zeppelin, like L44, seems to have attempted to find London but instead, traversed the Home Counties and Kent to exit at Dungeness. The raiders roamed England from early evening to around midnight. L55 was, for example, reported in the Skegness area at 19.30 and at Hastings, on the south coast at 22.15. Kptlt Flemming took his craft towards Boston, then cruised across the Fens in the general direction of Cambridge. In the vicinity of Wisbech he probably spotted the glow of L47’s calling cards exploding at Holme and Ramsey, prompting him to alter course towards those villages. Heading south again to London, L55 flew in an arc round the west of the capital, finally leaving these shores at Hastings.

In addition, L41 (Hptmn Manger) managed to find and bomb Birmingham and Northampton and L45 (Kptlt Waldemar Kolle), who came inbound through Yorkshire, may have been intercepted near Leicester by Lt Harrison in an FE2b from Stamford, as it was driven south to bomb London.

A large number of fighter sorties were flown that night, including BE2s from RNAS Cranwell and Freiston and FE2bs of 38 Squadron’s C Flight at Stamford, 51 Squadron’s B Flight at Tydd St Mary and C Flight at Marham. Of the fourteen night sorties launched by 38 and 51 Squadrons, Harrison was the only one who managed to actually fire – albeit ineffectually – at a Zepp that night, mainly due to the extreme altitudes at which the Zeppelins were flying. What the Home Defence fighters missed though, the weather and AA over France made up for. No less than five airships, nearly half the raiding force, were lost to one or the other cause.

The day – or rather the night – of the Zeppelin was almost over. Enemy air raids on England by day and increasingly by night were now in the hands of bomber aeroplanes. In the south of England, Gothas and Zeppelin-Staaken Giants were locked with British fighters in the first Battle of Britain. Peter Strasser and his decimated airship force were left to lick their wounds and it was March 1918 before the height-climbers were committed, though only in token numbers, once more.

Tydd St Mary airfield regained prominence for a fleeting moment for quite a different reason in April 1918. It was, in a way, almost as if the endless training flights, fruitless patrols and casualties discussed above, synthesised for a final fling with Germany’s airship fleet. Adverse weather had played its usual role in frustrating two airship attacks on northern England in March 1918, neither of which had affected the Fenland region. It was the night of April 12/13 before five latest-design Zeppelins of the L60 class roamed across the area once again. High altitude winds scattered this force along the east coast, with L62 venturing across the Fens to thrust inland to Birmingham, while L63 and L64 unloaded their bombs into the rural pastures of mid Lincolnshire. L62 flew inland from Cromer at nearly 20,000 feet, setting course for Birmingham. This route took her directly over the RAF (since April 1) station Tydd St Mary that, due to this enemy presence, was busy putting up its FEs on patrol. Fighters are recorded as taking off from 22.00 at Tydd and no doubt as a result of showing lights for this purpose, L62 was drawn like a moth to a candle.

The airfield rocked to the explosions of a stick of three bombs as the Zeppelin droned overhead. Of the three fighters launched by 51 Squadron from Tydd that night, only one spotted L62 as it flew majestically above the airfield. Lt F Sergeant in FE2b A5753 had to struggle to reach even 15,000 feet and after more than an hour chasing the airship without closing the gap, gave up near Coventry, returning to base while he still had fuel to do so. Another FE2b fighter from 38 Squadron (B Flight) airfield at Buckminster, spotted L62 at 01.00 hours as it was heading home from Birmingham, but although struggling to 16,000 feet, the pilot Lt Noble-Campbell was still too low to engage it. Lt W Brown in A5578 from C Flight at Stamford, patrolling between Peterborough and Coventry, also tried in vain to intercept L62. He and several other pilots crash-landed with engine failure – which sadly was an all too regular outcome of these night defence sorties.

Hptmn Kuno Manger released the remainder of his bomb load ineffectually in the countryside around Coventry then headed back to the coast at Great Yarmouth, where bad weather for a change helped protect her from the unwelcome attention of the fighters.

By 1918 a significant change to defence equipment was taking place. In order to combat the altitude advantage now enjoyed by Zeppelin airships and Gotha and Zeppelin-Staaken ‘Giant’ aeroplanes, quantities of Sopwith Camel, DH4 and SE5 fighters were diverted to Home Defence squadrons. Furthermore, specialist night fighters, such as a variant of the Sopwith Dolphin, were being tested. However, German aeroplanes had almost entirely taken over as the main bomber threat to England and air action was by now concentrated in the south and south-east of the country. A portent of years to come.

The Zeppelin menace reached a final climax in what became the last airship raid on England of the war, August 5/6 1918. Obsessed by his desire to re-establish the strategic credibility of his airship fleet, Fregattenkapitän Peter Strasser led this raid aboard the pride of his fleet, L70 (Kptlt Johannes von Lossnitzer in command).

Departing Nordholz at 15.30, this desire seems to have turned to impatience, since Strasser unwisely appeared off the Norfolk coast before darkness fell. Spotted early, off Wells-next-the-sea, at 20.00, L70 and its companion craft L65 and L53 were attacked by DH4 and Sopwith Camel aircraft at 18,000 feet just offshore. Two DH4s, A8032 piloted by Major Egbert Cadbury with Capt Robert Leckie acting as gunner and A8039, Lt R Keys with Air Mechanic A Harman, both from Great Yarmouth air station, quite separately attacked L70. So enormous was this Zeppelin that these two fighters were apparently completely unaware of each other’s attack. At 22.00 the effects of their incendiary ammunition had sealed the fate not only of the majestic airship but also of its crew of twenty-two men, including Strasser, who died along with his dream.

Primarily designed for bombing, the Great Yarmouth crews had found the two-seat DH4’s performance, when powered by a 375hp RR Eagle engine, effective at the altitudes at which the latest Zeppelins operated and could meet them on equal terms at last. Among the twenty-nine aeroplanes launched against raiders that night, FE2bs of 51 Squadron were airborne over the region but as none of the airships ventured inland, they found no trade. One, however, Lt Drummond from Mattishall in A5732, was obliged to make a forced landing at Skegness, fortunately without injury.

Although officially recorded as having crashed at 53.01N, 01.04E, because of darkness and cloud the true position of L70’s fiery plunge into the sea is unclear but appears to have been a few miles out to sea towards the mouth of The Wash. Next day major remains were found to have drifted onto sandbanks in The Wash in the vicinity of Skegness and Hunstanton. Witnessing from a distance the horrific end to L70, both companions turned tail for home and thus drew the night ‘shooting’ war in the region to a close.

It is not intended here to conduct a detailed analysis of WW1 air defence policy since other writers have dealt more than adequately with that subject. In the context of this account of one phase in the evolution of the night air defence of Britain, suffice it to say that airships represented German long-range bombing strategy of the time and the defenders were, for a long time, unable to contain them. They were thus, in theory, able to strike at any part of the British Isles. In practice, though, a degenerative cycle of circumstances brought about by factors such as: the sheer size of these weather-vane-like airships; perverse weather; poor navigation; limited radio aids and not least, intransigence among its leaders on the one side, opposed by steadily improving defensive aeroplanes, armament and searchlights on the other side – all severely curtailed the airship fleet’s effectiveness and caused it in effect, to self-destruct.

Of the 115 Zeppelins built:

25 were lost to enemy air or ground attack over England and the

continent

19 were damaged and wrecked on landing

26 were lost in accidents

22 were scrapped in service

7 were interned after being forced down

9 were handed over to the enemy at the end of the war

7 were ‘scuttled’ at the end of the war

About fifty crews were involved in German naval airship operations during the war and each crew could consist of up to eighteen airmen, so a total of no more than about 900 airmen made up the operational aircrew establishment, of whom about 400 lost their lives.

Just as in WW2, in this aspect of the enemy night offensive against England, the provinces outside the capital and the area around The Wash and Midlands in particular, saw a great deal more of the action than is generally appreciated. No less than eleven out of a total of fifty-four German airship raids on England (20%), directly or indirectly involved the region. Those particular eleven raids were mounted entirely by airships of the Imperial German Navy. Thus it has been shown here that the region felt the weight of this new form of warfare and aeroplanes based there played a small but important role in helping to defeat the menace. It will be seen next that, twenty-five years later, these provincial night skies would once more become a battleground – with a similar outcome for the protagonists.