As the war raged on, the Confederacy expanded its espionage activities, forming the Secret Service Bureau, a clandestine unit within the Confederacy’s Signal Corps. The bureau ran spy networks and covert missions out of Richmond, Canada, Great Britain, and Continental Europe. To finance the secret Canadian operations, Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America, signed this “warrant” (opposite page) requesting $1 million from the Secretary of the Treasury, payable for “Secret Service.”

Thompson, which appears at the upper left of the warrant, refers to Jacob Thompson, who would take the money, in gold, to Canada. A Washington insider, Thompson had served in Congress and had been Secretary of the Interior under President James Buchanan. He had no experience in espionage—or in sabotage, which was to be one of his missions.

In February 1864, the Confederate Congress had secretly passed a bill authorizing sabotage against “the enemy’s property, by land or sea.” Thompson’s $1 million came from the $5 million Secret Service fund granted by the Confederate Congress. The bill also allowed saboteurs to get rewards based on how much damage they caused.

Thompson’s star operative was Confederate Army Capt. Charles H. Cole, a veteran of battle who had been assigned to Secret Service missions operating out of Canada. Cole slipped into the United States and, assuming the identity of a Philadelphia banker, became an actor in a complex plot.

Near the U.S.-Canadian border were two large camps for Confederate prisoners of war. One was on Johnson’s Island, off Sandusky, Ohio, on Lake Erie, and the other was at Fort Douglas in Chicago. The Canadian plotters planned to take over Lake Erie passenger ships and then use them to seize the USS. Michigan, a warship that patrolled the lake for the Union. After seizing the Michigan, the conspirators would then attack the camp at Johnson’s Island and free thousands of prisoners. Joined with prisoners freed at Fort Douglas in another operation, the ex-POWs, along with anti-Lincoln militants, would assume control of the region and force the Union to end the war.

Cole, who had been given about $4,000 in gold for his mission, was supposed to charm the officers on the Michigan, get them to be less vigilant (perhaps by slipping drugs into their drinks), and signal when the ship was ready for boarding. The signal was to go to John Yates Beall, leader of a guerrilla band of about 20 men. They had seized a small passenger steamer that sailed between Detroit and Sandusky.

Beall waited in vain for the signal, unaware that the seemingly charmed or drugged Michigan officers had been tipped off about Cole by a Confederate prisoner aware of the plot. Beall, rightfully assuming that Cole had failed, sped to the Canadian shore, abandoned the ship, and set it afire.

Toward the end of the war, the $1 million in gold financed several other bizarre operations. About 20 men crossed the border to raid St. Albans, Vermont. They robbed three banks of about $200,000 and, trying to burn down the town, managed only to set fire to a woodshed.

A much larger incendiary plan was hatched for New York City in November 1864. Eight agents entered the city and obtained from a sympathetic chemist bottles containing a mixture of phosphorous and carbon disulfide that would burst into flame when exposed to air. The agents left open bottles in hotel rooms and a theater and broke a bottle on a stairway in P.T. Barnum’s American Museum. The fires were quickly put out, New York did not burn down, and no one panicked.

In December 1864, John Beall tried to derail Union trains near Buffalo. Union counterintelligence agents trailed him to a station where he waited for a train to Canada. He was tried and convicted as a spy and a guerrilla and was hanged. Union agents next caught Robert Cobb Kennedy, one of the New York arsonists. In his confession he admitted trying to set the museum on fire, adding “but that was only a joke.” He also was hanged.

Shortly after the war ended, Canadian authorities arrested another Confederate terrorist: Luke Pryor Blackburn, a Kentucky doctor. He was charged with conspiracy to murder in a foreign country. While in Bermuda caring for victims of a yellow fever epidemic, Blackburn had secretly collected victims’ sweat-soaked clothing and blankets and shipped them to Canada. Believing that yellow fever could be transmitted by the victims’ clothing, he hoped to start an epidemic in Northern cities. President Lincoln was to be presented with a gift of dress shirts packed with rags of fever victims’ clothing. Blackburn was acquitted for lack of evidence. He returned to his native Kentucky, where he resumed his medical practice and was elected governor in 1879.

Although the Confederates’ $1 million operation in Canada had little effect on the war, a plot discussed in Canada had profound consequences. Shortly before the Vermont raid, John Wilkes Booth arrived in Montreal and checked into a hotel that served as a Confederate headquarters. Rumors there swirled about plans by Booth and others to kidnap President Lincoln and hold him until he freed all Confederate prisoners of war; presumably they would fight again and help win the war. While in Montreal, Booth went to a bank and traded $300 in gold coins—presumably Confederate gold—in a currency transaction. (He later left for New York, where, coincidentally, he was on the stage of a theater when the Confederate arsonists struck.)

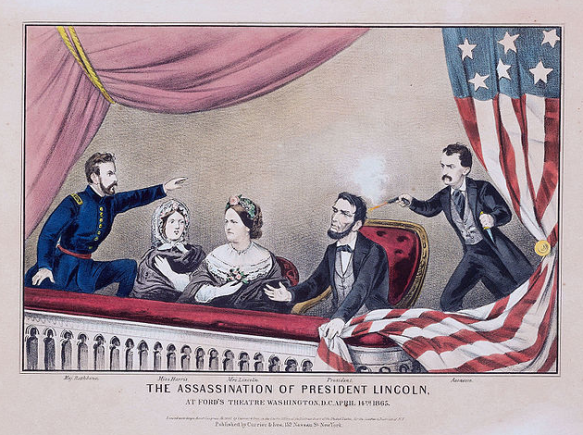

The kidnapping was to take place in March 1865. But a change in Lincoln’s schedule thwarted Booth and his associates. After Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865, there was no need for a kidnapping; the war was over. But five days later, Booth, on his own, changed the plan from abduction to assassination, with the aid of others in the original plot. Booth entered Ford’s Theatre in Washington on the evening of April 14, opened the door of the presidential box, shot Lincoln in the back of the head, leaped to the stage, shouted “Sic Semper Tyrannus”—“Thus always to tyrants”—and escaped. Lincoln died the next morning. On April 26, Booth was killed while resisting capture, and the full story of the original plot died with him.