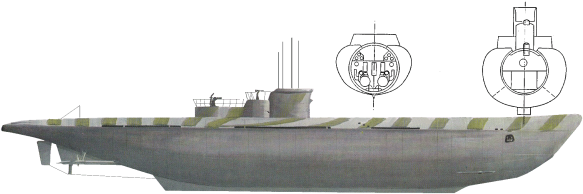

The extension of the U-boat war to the American coast in January 1942 created a problem for Karl Dönitz C-in-C U-boat command. Because it took his submarines substantially more time to get to and from their rich target areas off New York or Virginia or Florida than it took to reach patrol lines off Newfoundland or Nova Scotia, their combat time was reduced. To prolong their battle period as much as possible, he resupplied the U-boats at sea, using special submarine tankers. These “milch cows,” twice as big as the standard Type VII combat submarines, carried 400 tons of fuel oil, 50 tons of provisions, a workshop, a physician, and personnel to replace injured or sick combat-sub crewmen. When the first U-tanker began work in March 1942, a U-boat averaged 41 days at sea. With one resupply, this time was extended to an average of 62 days and, with two, to a maximum of 81. Even for the more northerly operations, refueling was essential for efficiency. Experience showed that submarines had to spend from three to five weeks in the operational area before encountering a convoy in a favorable position. This meant that to make success likely, Type VIIC boats had to be refueled twice. After twelve months, by May of 1943, the U-tankers had completed 390 refuelings.

It became clear to the Allies that sinking one milch cow would reduce the effectiveness of many combat U-boats. They were unable to plan such an attack during the codebreaking blackout of 1942 because they could not read the instructions for the refueling rendezvous, and U-Boat Command had taken care to have the submarines meet in remote locations, far from the convoy tracks and out of the range of Allied airplanes. The U-tankers maintained radio silence. Instructions were enciphered in the special officer-grade keys and then reenciphered in the general key; the grid encipherment disguised positions. In 1943, however, with codebreaking restored, it became possible for the Allies to attack tankers. The solved messages sometimes disclosed the date and place of a refueling rendezvous; when these specifics were not available, the O.I.C.’s knowledge of the departures and movements of the supply submarines and of favorite refueling areas could guide ships and airplanes to likely hunting grounds.

But three factors saved the supply submarines for a while: the inability of Allied aircraft to reach the rendezvous, the need for surface forces to stay close to convoys, and the adamant refusal of the British to attack the isolated refueling points for fear that the Germans would guess that their cipher system had been solved. This refusal stemmed originally from the anxiety the British had experienced after the 1941 roundup of Bismarck supply ships, when two that were to be left alone so as not to raise German suspicions were accidentally attacked. Their decision was hardened by leakages that could be traced to Enigma solutions, by four cases in which Enigma solutions were repeated almost verbatim in British messages, and by a scare in March 1943.

The Kriegsmarine, an intercept showed, had grown suspicious about British warships sighted in an area where they would have encountered a German convoy bringing supplies to North Africa had the convoy not been delayed. The first sea lord reprimanded the Mediterranean commander in chief, and Churchill threatened to withhold Enigma intelligence, or ULTRA, unless it was “used only on great occasions or when thoroughly camouflaged.” At the same time, the first sea lord emphasized in a personal message about ULTRA to his American counterpart, Admiral King, his anxious desire that “we should not risk what is so invaluable to us.” The next month he resisted American proposals for using Enigma U-boat solutions to attack U-tankers at their supply rendezvous, arguing that “if our Z [ULTRA] information failed us at the present time it would, I am sure, result in our shipping losses going up by anything from 50 to 100%.”

But this risk declined late in May, when Dönitz pulled his submarines out of the North Atlantic. And a few weeks later an event showed how Enigma information, while still used with great care for its security, could greatly enhance the new offensive strength of the Allies at sea. This new strength consisted of the Americans’ introduction of task forces centered on small, “escort” aircraft carriers. These could bring airplanes to within striking distance of a refueling rendezvous. On June 12 the escort carrier Bogue, using information from both Enigma decrypts and direction-finding, sent out airplanes that, shortly after noon, spotted the 1,700-ton converted minelayer U-118 cruising placidly on the surface. The planes bombed and strafed her, drove her under, and, when she resurfaced, sank her. Her loss forced U-Boat Command to recall some submarines and delayed other combat boats in reaching their target areas. These disruptions, mentioned in Enigma intercepts, showed the Allies the value of attacking the U-tankers—a demonstration that was reinforced in a negative sense when the tanker U-488 refueled twenty-two boats to overcome the emergency. As a consequence, the Americans pressed to use Enigma information against the supply subs. By this time the British fears of the loss of ULTRA were allayed because using aircraft to spot the submarines covered their reliance on cryptanalytic intelligence, so Britain concurred in the American proposal. Enigma solutions now enabled the escort carriers to carry the war to the enemy. For the first time, the Allies attacked U-boats not just defensively, as in fighting off wolfpacks, or fortuitously, as when a plane spotted a submarine, but actively—aggressively seeking out subs and hitting them. Enigma decrypts had changed from a shield to a sword.

#

Among the targets of these machete chops was the U-117, a sister ship of the U-118. She had taken her crew of fifty-odd on three supply cruises when, on July 22, 1943, she sailed from France under the command of Lieutenant Commander Hans-Werner Neumann as one of five supply submarines that Dönitz sent to sea in the last third of July. Three of these were sunk while crossing the Bay of Biscay before the end of the month; a fourth was destroyed west of the Faeroes. This put additional pressure on the U-117 to meet and refuel combat submarines that otherwise might not have been able to return home.

One of these was the U-66, a veteran boat that had completed nine patrols in areas ranging from Cape Hatteras to the Mediterranean, had landed a saboteur on the northwest African coast, claimed to have sunk 200,000 tons of shipping, and had provided each of her two commanders with a Knight’s Cross to the Iron Cross. On this cruise she had been at sea the extremely long time of three months, during which time she had sunk two American tankers. On July 27, U-Boat Command ordered her to square CD 50, about halfway between Washington, D.C., and Lisbon, Portugal, to rendezvous with the U-117 for reprovisioning.

The message was intercepted. But it had not yet been solved when the cryptanalysts read a message giving a new rendezvous for 8 P.M. August 3. The solution gave the location as “square 6755 of the large square west of” another square, which was disguised by the grid encipherment but which the cryptanalysts thought was CE. This would put little square 6755 in large square CD, making it 37° 57′ north latitude, or roughly east of Washington, D.C., and 38° 30′ west longitude, or north of the bulge of Brazil.

At 1:05 P.M. Eastern War Time, August 1, 1943, the U.S. Navy’s codebreaking unit on Nebraska Avenue in Washington, D.C., teletyped a solved intercept to F-21, the Atlantic section of the Combat Intelligence section of Cominch, where the Submarine Tracking Room was located.

The message was about twelve hours old, the time it took for Commander Engstrom’s back-room boys to crack it and the translators and evaluators to append to each U-boat commander’s name the number of his submarine and the latitude and longitude of its naval grid references. They put these insertions in double parentheses to show that they were not part of the original message. The first part of the text directed two submarines not to refuel but to proceed home. The second and more interesting portion, however, dealt with the U-117: “Neumann ((117)) head for Nav Sq 67 ((probably CD 67 = 37.57 N – 38.30 W)).”

Fifteen minutes later, the teletypewriter tapped out another solved German message. Sent ten hours after the first, it instructed the U-66’s captain, Lieutenant Friedrich Markworth, where and when to get supplies: “Beginning 3 August 15 2000B Markworth ((66)) will provision from Neumann ((117)) in Sq 6755 ((probably CD 6755 = 37.57 N – 38.30 W)).… After execution Markworth report affirmative, Neumann wait in that area.”

The day after these messages went to F-21, Cominch headquarters radioed the information to units at sea that could use it. It was included in the U-boat report for August 2. Not giving the source of the intelligence, the report stated: “Several [U-boats] area 3800 [north] 3830 [west].” The data were repeated in the next day’s report, with a cover source: “Several vicinity 3800 3830 by recent DFs suggesting refueling operations X.”

One of the recipients was the U.S. Navy’s Combat Task Group 21.14, a convoy support group consisting of the escort carrier Card and three old destroyers. The U-boat situation reports told its commander, Captain Arnold J. (Buster) Isbell, where to look for subs to sink. He knew that if refueling, they could be caught at a particularly vulnerable moment—moving slowly on the surface, joined by a fuel hose—and that one of them would be a particularly valuable target. He headed toward the reported U-boat concentration while his planes scouted ahead and to the sides.

#

Late in the afternoon of August 3, as the Card was perhaps 150 miles from that area, two of his pilots, reserve Lieutenant (j.g.) Richard L. Cormier, in a Grumman TBF-1 Avenger torpedo-bomber, and his wing-man, reserve Ensign Arne S. Paulson, in a Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat fighter, making a routine submarine search, were flying southwest at 5,000 feet in clear skies when Cormier, with his binoculars, spotted a grayish white submarine off to port about 11 miles away. She was fully surfaced, cruising so slowly that no bow wave or wake was noticeable. It was the U-66.

Paulson, on Cormier’s orders to strafe the submarine, gave his fighter full throttle and, 100 feet above the waves, raced directly at the U-boat. At 500 yards, he began firing and saw his bullets strike the conning tower, kicking up puffs of rust. He saw nobody; on the U-boat, however, a machinist who was topside smoking was wounded in both thighs. Cormier then swept in to depth-charge the U-boat, but the charges failed to release. As he circled to attack again, Paulson made another run. It was met at this time with inaccurate antiaircraft fire from the six or eight men now topside. The attack had, however, killed the submarine’s second watch officer and panicked the men in the conning tower into ringing the diving alarm. But Markworth, demonstrating anew why he had won the Knight’s Cross, bulled his way up the ladder, belayed the command to dive, and held his men to their guns.

In his torpedo-bomber, Cormier sped toward the U-boat, skimming the water. He pressed his electrical bomb release and immediately pulled the emergency release. This time his acoustic torpedo and both depth charges dropped. Within seconds, while making a climbing turn, he saw a shock wave centered about 25 feet from the submarine’s starboard side and just forward of her conning tower. It swept to her port side and appeared to lift her from below and make her list to port. Then a heavy column of water about 100 feet high obscured the U-boat. When she reappeared, she was turning to starboard. Paulson attacked again. He saw half a dozen figures, some inert, on the conning tower. His shots killed one sailor who had kept firing despite several wounds, wounded another in the chest, and slightly injured six others. No further fire was returned. Cormier strafed, seriously wounding Markworth in the abdomen. Then it became clear to the men on the submarine that the planes had no more bombs and that it was therefore safe to dive, so the first watch officer gave the order. The bodies of the officer and the seaman had to be left where they were. Slowly at first, and then more rapidly, at an angle of 50 degrees, the U-boat submerged. Just as she was disappearing, Paulson made a final run, firing at the underside of the stern.

Cormier dropped a marker and circled over the spot for forty-five minutes. Though neither he nor the pilots of the other planes that the Card sent saw any debris, oil, or air bubbles, the squadron commander claimed a sinking. He was wrong. Though the U-66 had two fatalities, several seamen wounded, and a captain suffering from a bullet in his guts, and though her ballast and fuel tanks were leaking, she had escaped.

But she still had not met the U-117. She limped east toward home, with not enough fuel to make it and only two days’ worth of provisions. The next day, after midnight, she surfaced. Though the sailor’s body had washed overboard, the second watch officer’s body was, ghoulishly enough, still on the lower machine-gun stand. It and the body of a sailor who had died from his wounds were buried at sea.

Meanwhile, Buster Isbell on the Card was being further tantalized by F-21’s U-boat situation reports to his carrier task group telling of combat and tanker submarines nearby. On August 6, for example, he was told, “One probably refueler locality 3915 3730 by DFs 052330 and 052350 probably moving NE.” By 2 P.M., he was steering for that area.

That same day, the U-66 proposed a new rendezvous with the U-117 for that noon, some 54 miles north and 12 miles east of the August 1 meeting place. Dönitz acquiesced a few hours later. The Allied cryptanalysts could not read these messages as promptly as the others, and they remained a closed book. But the Tenth Fleet’s ULTRA-based knowledge of the rendezvous attempts, together with its background information that on July 30 the U-117 had been ordered to stand by within 100 miles of 38° 50′ north, 37° 20′ west, a circle within which the August 1 rendezvous was to have been effected, made it worthwhile to keep the Card in the vicinity.

Shortly before noon on Friday, the U-117 and the U-66 finally met. After dark the combat submarine took aboard some provisions and a physician to treat Markworth. But, unable to refuel at night, the pair waited for morning. With daylight, the U-66 began to take on oil. At just about the same time, 6:49 A.M. Saturday, the Card flew off the same kind of airplane pairing as had attacked the U-66, an Avenger and a Wildcat. An hour into the patrol, however, the Wildcat had to return to the carrier because of engine trouble. The Avenger, piloted by reserve Lieutenant (j.g.) Asbury H. Sallenger, continued its routine submarine search. At 9:46, while flying west-northwest at 4,500 feet in a cloudless sky, Sallenger spotted a large white object 15 miles off his starboard bow. He thought at first it was a merchantman, but he soon realized that it was two submarines, painted white, close together, fully surfaced and proceeding very slowly southwest, with neither bow waves nor wakes. The refueling was still in progress.

Sallenger radioed the Card, 82 miles away, and maneuvered to attack. Selecting the U-boat nearest him, which was slightly behind the other, he approached from the port quarter at 220 knots, out of the sun. “This is it!” he told his crew. The U-66, spotting him, shoved the throttles of both diesels to full speed ahead. When Sallenger was about 400 yards from the subs, both opened fire with their 20-millimeter guns. These filled the sky with white puffs, but Sallenger bored in and, from about 125 feet, dropped two depth charges, set to explode at 25 feet. They straddled the U-117. Three seconds later the explosions raised two columns of water on the starboard side, one about 10 feet out, the other some 20 feet out, cutting the refueling hose. Sallenger banked to the left and climbed. The submarine spurted flame from its stern, and dense gray smoke rolled out. The TBF’s turret gunner, Ammunition Mate Third Class James H. O’Hagan, Jr., sprayed the deck with his .50-caliber machine gun, then concentrated his fire around the machine guns on the conning tower. He saw about twenty men. The radioman took pictures, which would be used to improve tactics.

The U-boat began maneuvering erratically, as if her steering apparatus had been damaged. She started to trail a heavy oil slick. The U-66 was following her, seemingly trying to help. After about fifteen minutes, the undamaged U-66 started to submerge, apparently in an attempt to save at least herself. While she was thus vulnerable, Sallenger, who had been watching from 6,500 feet, dove to attack. As he flew along her track at 130 knots in level flight, 200 feet up, the U-117 threw intense antiaircraft fire at him. O’Hagan fired back. Sallenger dropped his acoustic torpedo on the last seen course of the submerged U-boat, 150 yards ahead of the diving swirl and 50 yards to starboard some forty seconds after she disappeared. Sun glare prevented him or his crew from observing any results. But the U-66 escaped.

His armament exhausted, Sallenger soared to 6,400 feet to vector in the other planes. As he circled, the damaged U-tanker tried to dive. For a moment, Sallenger thought she was gone, but she surfaced almost immediately. At 10:33 A.M., twenty minutes after his second attack, two Avengers and two Wildcats arrived from the Card. On command, one of the fighters made a strafing run. He fired a test burst from 2 miles away, but the bullets fell short, and he held his fire until he was in range. During his run, gun flashes from the 20-millimeters at the base of the conning tower winked at him, and he concentrated his fire on this area, though he saw no gunners; apparently they were well protected. He swooped around and attacked from the other side. But the U-boat continued her heavy antiaircraft fire, which forced the lead Avenger, flown by Lieutenant Charles R. Stapler, to weave as it bored in. In a shallow dive, Stapler released two depth charges at 185 feet. They fell close aboard the port side just ahead of the conning tower, and the explosion drenched the submarine. As Stapler pulled up, his gunner strafed the vessel. The first fighter again attacked, and so did the second, just before the second Avenger, coming from the U-boat’s stern, dropped its two depth charges 20 to 25 feet from the submarine on her starboard quarter. Spray covered her. The fighters zoomed down to strafe some more, finally silencing the antiaircraft fire.

As the two Avengers circled, the crippled U-117 turned to starboard, apparently trying to dive but instead only mushing down, stern first. Then she did go under, and the Avengers turned to attack with their acoustic torpedoes. But they pulled up when the bow and conning tower broke water and the submarine, now barely moving, struggled to surface. Quantities of oil leaked from her. After five minutes, she lost the fight. She began to settle. Her stern went down, her bow rose slightly; the conning tower slipped under, then the bow, and she was gone. Now the Avengers could use their acoustic torpedoes. Stapler dropped his 200 feet ahead of the oil slick and 100 feet to starboard of the U-boat’s last track. Ten seconds later, the other Avenger dropped its 400 feet ahead and to port of where the pilot had last seen the submarine. Some distance away, the crew of the U-66, still submerged, heard detonations, some sharp, some muffled.

The Avengers circled. A patch of oil 200 feet in diameter where the submarine had last been seen seemed to grow. The radioman of the second Avenger reported seeing a shock wave in the water forward and to starboard of the same point. The U-66 heard crackling noises, and finally sounds that the crew interpreted as those of a boat sinking. The airmen saw a very light blue area that seemed to be caused by small bubbles aerating the water. This persisted for many minutes. Nothing else was seen. At 11:26 the four planes were recalled to the Card. They were relieved by three Avengers which, however, saw neither submarine. Though Isbell claimed that one submarine had been “definitely sunk” and the other “probably sunk,” he was only half right. The U-66 had escaped. But the U-117 had made her last dive. She had gone down about 17 miles north and 40 miles west of where the August 6 U-boat situation report had told Isbell that “probably refueler” would be found. In the vast wastes of the ocean, that was practically pinpointing the target.

Reporting the episode early Sunday morning, the U-66 did not tell U-Boat Command about the detonations she had heard. U-Boat Command, assuming that the U-117 had survived, gave both submarines a new rendezvous for noon. Later the command observed that with the loss of another milch cow, the last fuel reserve for boats coming from the south had been exhausted, and all fourteen had to refuel now from the U-117. But when the U-66 reported on Wednesday that it had waited two days in vain for the U-117, and when the tanker failed to respond to orders to report, the command concluded that she had been lost during the attack. The critical supply situation forced U-Boat Command into complicated maneuvers: some combat submarines had to give fuel to other boats, then return home using fuel as sparingly as possible. The U-66 made it. The loss of the tankers, Dönitz complained, forced him to end operations in the mid-Atlantic earlier than planned.

Between June and August, American carrier planes, aided by ULTRA, sank five milch cows and reserve tankers. The British lost all reservations about using Enigma intelligence in these operations. On October 2 the Admiralty asked the U.S. Navy whether it could send a task force against a refueling to take place north of the Azores; Navy planes found four U-boats on the surface and sank the milch cow U-460. A similar request less than a week later ended in the sinking of the combat boat U-220. By the end of October, of the ten milch cows that Dönitz had had in service in the spring only one remained. The effect on U-boat operations was severe. Because resupply by U-tankers was so dangerous, Dönitz avoided it, compelling his U-boats to break off their operations correspondingly early and destroying his hopes for a formidable offensive in distant waters, far from Allied air cover. In November he abandoned the convoy routes as a theater of operations.

But he returned to the fray the following month. When a patrol line failed to find any ships, he broke it up into subgroups of three boats each in the hope that they would spot targets. It didn’t work. Between mid-December 1943 and the middle of January, they sighted not one of the ten convoys that sailed close to them, and they sank only one merchant ship. At the end of February, Dönitz formed what would be the last wolfpack worthy of the name. PRUSSIA’s sixteen submarines sank two small British warships—at a cost of seven U-boats. On March 22 Dönitz ordered another withdrawal. In the first three months of 1944, his U-boats sank only 3 merchantmen in convoy out of 3,360—at a cost of thirty-six submarines. He persisted with his “wonder weapons”—the acoustic torpedo and the snorkel, a valved tube to the surface that enabled a submarine to run on its diesels while under water, increasing its submerged speed and range. But he concentrated now on sinking shipping around the British Isles for the expected invasion of western Europe.

ULTRA had little effect on this. The few U-boats dotting the Atlantic posed little threat. The vast convoys, sometimes of hundreds of ships stretching from horizon to horizon, proceeded majestically across the broad expanse of the Atlantic, guarded by sea and by air, bringing the men and materiel that would drive a stake through the heart of the wickedest regime the world had ever seen. With the help of ULTRA, the Battle of the Atlantic had been won.