As the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) waned, the Jurchens (Manchus) led by Nurhaci started to consolidate power in northeastern China. Although Nurhaci monopolized the trade in the region, he recognized the importance of creating an effective and powerful military apparatus in order to unify the Jurchens and to realize the goal of empire building.

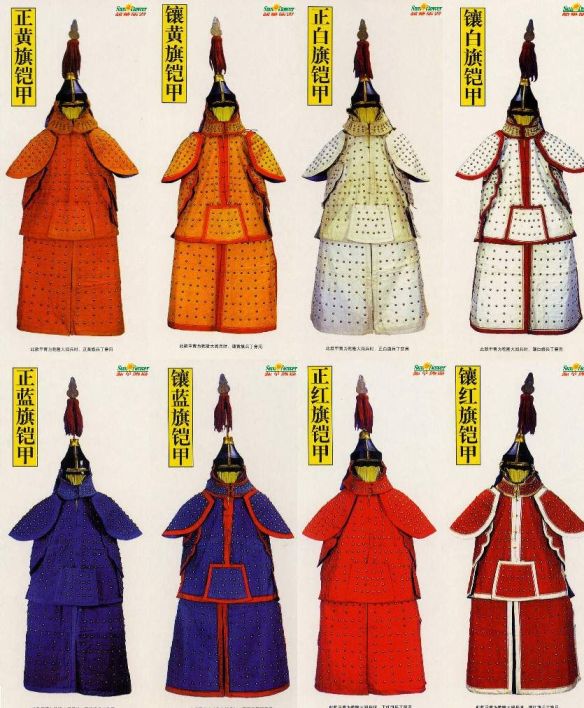

In 1601, Nurhaci created the banner system by organizing the Jurchens into four banners with four basic colors as identifications: yellow, white, red, and blue. As he recruited more warriors, he created another four banners in 1615: banners with flags embroidered with the four original colors. Historically, this system is called the Eight Banner System.

The banner system was administered through three levels: banner (gusa), regiment (jalan), and company (niru). The whole system functioned as a military force as the banners served as a tool in wars, and a membership in a given banner symbolized the status as a warrior. The stratification of the banner into three levels facilitated effective commandership as all banner men were required to be loyal to Nurhaci. To strengthen fighting capability, Nurhaci’s descendants added eight Mongol and eight Chinese banners in 1634 and 1642.

The banner system was also a political polity as well as a social organization. Principally, all Manchus, Mongols, and the Chinese who surrendered early were banner men. The distinction between soldier and civilian was vague, and they were identical in many cases. At peace, banner men engaged in farming and Banner System I 19 receiving military training; they were dispatched to the front once a war broke out.

When the Manchus conquered China in 1644, the total number of soldiers in the banner system reached 168,900. After 1644, the banner system became a hereditary military caste. By the end of the seventeenth century, the number of banner men totaled a quarter million, a stable figure until 1912. Roughly half of all banner men and their families were stationed in Beijing (Peking) as defenders of the capital. Over 100 banner garrisons were established in major cities or strategic locations throughout the Qing dynasty (1644- 1912), such as those along the Grand Canal and the Yellow River (Huanghe) and Yangzi (Yangtze) Rivers, in the coastal regions, and in the northeast and northwest. A garrison inside a major city was called the “Manchu City” separated from Chinese civilians to avoid direct confrontation. Being in those isolated colonies, the garrisons remained one of the prominent institutions of the Qing dynasty.

Although the banner troops originally were fierce fighters, their life in a new environment in vast Chinese land eventually debilitated their militant spirit. The emperors often issued edicts to remind them of preserving tradition, but the banner system was gradually eroded by banner men’s indulgence in an enjoyable life. In 1735, barely a century after the Manchu conquest, Emperor Qianlong (Ch’ienlung) (reigned 1736-1795) started to rely on the Chinese Green Standard Army to suppress bandits and uprisings. Even though banner men continued to be a state-sponsored military force, they were no longer a regular army.

The banner system proved to be ineffective during the First Opium War (1840-1842) and the Taiping Rebellion (1851-1864). As a result, Hunan (Xiang) Army and Anhui Army replaced it. By the end of the nineteenth century, the rise of the New Army (Beiyang Anny or Xinjun) disfranchised the banner system as a military force.

As imperial decay continued, the banner system became a burden to the Qing government, as the state funding diminished. Consequently, banner men lived in poverty and were encouraged to seek self-support. Banner men in urban areas such as Beijing were absorbed into the urban labor force, while those who lived in frontier regions such as Heilongjiang (Heilungkiang) Province became farmers. The Chinese Revolution of 1911 and the abdication of the last Qing Emperor Xuantong (Puyi) (1909-1911) declared the demise of the banner system.

References Crossley, Pamela Kyle. Orphan Warriors: Three Manchu Generations and the End of the Qing World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990. Di Cosmo, Nicola, ed. Military Culture in Imperial China. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009. Elliott, Mark C. The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. Powell, Ralph L. The Rise of Chinese Military Power, 1895-1912. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1955. Rowe, William T. China’s Last Empire: The Great Qing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009. Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China. 2nd ed. New York: W. W. Norton, 1999