Duke of Marlborough’s quartermaster-general, William Cadogan (1675-1726), served him throughout the War of the Spanish Succession. He was the duke’s right-hand man, ready to lead the vanguard of the army on the march, carry out reconnaissance, draw up detailed plans for movement or battle, organize supplies, and if necessary command troops in combat. Cadogan also shared in Marlborough’s systematic pursuit of financial profit and remained a loyal follower during his subsequent fall from favour.

Marlborough’s Quartermaster-General, William Cadogan, who evidently believed himself most fortunate to have avoided the attentions of French hussars when he was made a prisoner of war in 1707:

I was thrust by a crowd that I endeavoured to stop into a ditch [he wrote in a letter to Lord Raby]. With great difficulty I got out of it, and with greater good fortune escaped falling into the [French] hussars hands, who first came up with me. A little resistance I persuaded some few of the dragoons I had before made alright, and who could not get to their horses, saved them and me, since it made me fall to the share of the French carabines [sic] who followed their hussars and dragoons, from whom I met with quarter and civility, saving their taking my watch and money.

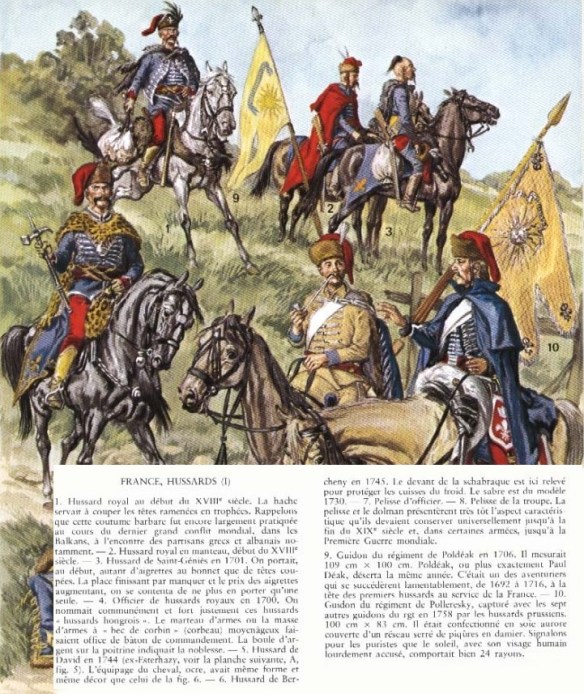

It would seem from such evidence that the hussars enjoyed a somewhat barbarous reputation.

In the English service, Marlborough himself was Colonel of the 1st Foot Guards from 1701-12 and from 1714-22, being succeeded by his old friend, commander-in-chief the Earl of Cadogan.

Marlborough’s right-hand man at the head of the Allied army was undoubtedly his quartermaster-general, William, First Earl Cadogan (1671-1726), whose grandfather had moved to Ireland in the 1630s and became secretary to the ill-fated Earl of Strafford. Intended for the law, and studying at Trinity College in Dublin, at the age of 17 he became a cornet in Wynne’s Regiment of Dragoons in William III’s army, fighting at the Battle of the Boyne in 1689 against James II when that exiled king attempted to regain his throne. Cadogan also served at the Battle of Aughrim in 1690 and the subsequent capture of Cork and Kinsale, meeting the Earl of Marlborough (who was present on the instructions of Queen Mary, who was acting as regent in her husband’s absence from London on campaign) for the first time. By 1694, Cadogan was a lieutenant in Erle’s Regiment of Foot, campaigning in the Low Countries against France, and taking part in the famous siege of Namur the following year, when Marshal Boufflers was obliged to yield the fortress – the first time a Marshal of France had ever done so. In August 1698, Cadogan managed to secure an appointment as major and quartermaster in Ross’s Dragoons and returned with that regiment to Ireland on the temporary peace that had come with the Treaty of Ryswick. Marlborough appreciated Cadogan’s good qualities and capacity for hard work, and in June 1701 he had the young man promoted to lieutenant colonel.

Once active campaigning in the Low Countries began in 1702, Cadogan fulfilled the additional function of chief of staff for Marlborough and proved to be a first-class soldier with a good eye for ground, enormous energy and a fine capability both as a tactician and as a staff officer. He had an exuberant and boisterous manner, however, which occasionally gave offence, but Cadogan’s close friendship with Marlborough, and the way in which the duke could depend upon him, almost without question – as chief of staff, quartermaster-general and unofficial director of military intelligence – was a marked feature of the many campaigns that the two men shared during the war. This bond was widely acknowledged to a rather surprising degree, as when Cadogan was taken prisoner in 1706. The newly appointed French army commander, the Duc de Vendôme, arranged his early release, in exchange for a senior officer in Allied hands, as he knew how much Marlborough valued Cadogan’s services. Such consideration reads rather oddly today, but seems to have attracted little comment at the time. Marlborough did indeed value Cadogan’s grasp of terrain and the vital elements of time and space in which to achieve things, and the quartermaster-general’s temporary absence from the Allied camp in the summer of 1708 is sometimes given as the main reason for Marlborough being caught out by the sudden French offensive to take Ghent and Bruges. Francis Hare certainly thought so, and wrote of Cadogan at that time, `He would have known the difference between their coming to us and marching by us and would have given His Grace better intelligence.’

British quartermaster and general. He rose rapidly in rank under the patronage of Marlborough, who made him a staff officer and confidant from 1701. His regiment, “Cadogan’s Horse” (later, the 5th Dragoon Guards), became famous in British military history. He was enormously effective as quartermaster during Marlborough’s famous march to the Danube in 1704, a feat notable above all for its logistical accomplishment. His skills were put to the test on the long march from the Low Countries to the Danube. The logistical challenge was enormous, but Cadogan carried out his tasks to Marlborough’s complete satisfaction. The army’s financial agent in Frankfurt ensured that sufficient funds were made available at all stages of the famous march so that supplies and necessaries of all kinds were readily available – food for the men, fodder for the horses, shoes, horseshoes, quarters and camping grounds – nothing was seized, everything was paid for. `Surely,’ wrote Captain Robert Parker of the Royal Irish Regiment, `never was such a march carried on with more order and regularity.’ Cadogan’s duties did not keep him out of the line of fire, and he was injured and had his horse killed under him at the storm of the Schellenberg in July 1704.

He served directly under Marlborough at Blenheim (August 13, 1704). In 1705 he led his regiment in forcing a section of the Lines of Brabant for Marlborough, which changed the whole structure of the northern theater during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714).

John Lynn has categorised Louis XIV’s style of command as guerre du cabinet. It was not exclusive to France. Many features of guerre du cabinet can be recognised in the yearly cycle of Louis XIV’s nemesis, Marlborough, who cannot possibly be seen as an armchair general but who nevertheless generated a prodigious correspondence from the field. Marlborough maintained it between campaigning seasons through the agency of his quartermaster-general, William Cadogan, who often remained on the continent all the year round, preparing options for the following season, and evolving into something very like a chief of staff in modern parlance. The general’s winter was spent usefully in England `schmoozing Conservative politicians’ – Mark Urban’s colourful phrase – as well as securing relationships with his wife and the queen.

Beyond the village of Merdorp, the ground falls into a gradual incline. There, at 8 a. m. in fog-laden daylight, Cadogan crossed paths with a party of French hussars. Cadogan held firm on the rise as the Guards exchanged fire with the French, who swiftly retired. Just then the mist began to dissipate. Before Cadogan’s eyes lay a broad sweep of gently undulating, open country, free of trees and hedges.

With his spyglass, Cadogan could see movement highlighted by the sloping sunshine on high ground some four miles to the west. Through the ever-thinning mist rode Villeroi’s advance guard. Cadogan promptly sent a courier back to Marlborough, warning him of the enemy’s proximity.

Cadogan led the advance guard of cavalry that brushed into the French cavalry rearguard of Vendome’s army, precipitating a rare battle of encounter at Oudenarde (July 11, 1708). On the night of July 6, the allied army camped at Asche, about 10 miles northeast of the point where the French crossed the Dender. Prince Eugene, worried that a battle would occur before his troops could reach Flanders, dashed ahead of his troops and arrived at Asche to join the army.

Eugene and Marlborough believed that to cover their move against Oudenarde the French needed to take Lessines, a town on the Dender. The allied commanders intended to get to Lessines first. Leaving Asche at 2 AM on July 9, the allied vanguard under Maj. Gen. William Cadogan reached Lessines at midnight after a march of almost 30 miles. By the time the rest of the allied army arrived, Cadogan’s men had several pontoon bridges ready. The army pressed on toward Oudenarde in anticipation of a battle on the south bank of the Scheldt in front of the city.

Vendome and Burgundy now had an enemy army between them and France. They altered their plans and aimed to cross the Scheldt a few miles downstream from Oudenarde. Then, on the left bank of the river, they would be able to fend off an attack and either move against Oudenarde or protect Ghent and Bruges. It was a cautious strategy to be sure, but such prudence fit with Louis XIV’s desire to avoid ruinously expensive battles when possible.

One of the few things that the quarreling French commanders agreed on was their belief that the allies would linger around Lessines for a while. So it was 10 AM on July 11 before the French even started over the Scheldt at Gavres, about 21/2 miles northeast of Oudenarde.

In contrast, the allies moved with surprising speed. Early on the morning of July 11, Marlborough detached Cadogan to move ahead to the Scheldt and occupy the village of Eine, just northeast of Oudenarde. With Cadogan were 16 battalions of infantry, 30 squadrons of cavalry, and 26 guns. The rest of the army departed from Lessines in Cadogan’s wake.

Cadogan was to prove himself as a battlefield tactician that day. After another swift march, Cadogan had his first detachments across the Scheldt by about 10 am. His engineer troops swiftly assembled five pontoon bridges just east of Oudenarde. Marlborough’s men called their pontoons tin boats, as the wooden pontoons were covered with sheets of metal to protect the hull planking.

In January 1709 Cadogan was made lieutenant general, and when he was wounded during the siege of Mons in the autumn, Marlborough wrote to his wife expressing keen concern for the swift recovery of his close friend. The two men certainly had found that they thought and acted in accord, and while preparing for a siege and riding on a scouting expedition, Marlborough dropped his glove, as if by accident, and asked Cadogan to recover it for him. This was done, and that evening the duke asked if he remembered the spot and, if so, to have a battery emplaced there; the quartermaster-general was able to respond that he had already given the necessary orders for this to be done. He stayed loyal to Marlborough after the Duke’s dismissal in January 1712, thereby losing his own ranks and offices to the wrath of the Tories. He was reinstated by George I in 1714, in time to participate in the fight against the Jacobite rising that year.

He became Colonel of the 2nd English Foot Guards (the Coldstream) in October 1714 and was employed on diplomatic duties at The Hague, a role for which he showed great aptitude, despite his hectoring manners, assisted, no doubt, by his ability to converse in the language. One of Cadogan’s more questionable actions was to have the tails of all horses in Queen Anne’s regiments docked, as they looked `neater’ that way – a strange custom that would persist for many years.

During the 1715 Jacobite rebellion, Cadogan was appointed to replace the Duke of Argyll as commander in Scotland, a rather unnecessary move as Campbell had already asked to be recalled to London. Created Baron Cadogan of Reading in 1716, his later career was not without controversy or mishap, and he became embroiled in a lengthy and regrettable argument with Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, over a large sum of money which she had asked him to invest safely. Instead he placed the funds in more speculative investments, hoping perhaps to reap the difference in anticipated return as his own profit, but then lost heavily and eventually had to repay the sum to the duchess.

Cadogan had been Member of Parliament for Woodstock, near to Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, for many years, but when he attempted to be elected as Member of Parliament for Reading in Berkshire, the liquid inducements offered to persuade voters flowed a little too freely and a sprawling riot broke out in the market square.

In 1717, Cadogan was appointed to be general of all the Foot forces (infantry) of the crown, as Marlborough’s health was fast failing, and that same year he signed the Treaty of Triple Alliance with Holland and France, on behalf of the king. He became an earl in May 1718, was made the Captain-General in 1721, and on Marlborough’s death the following year appointed to succeed him as Master-General of the Ordnance and Colonel of the 1st English Foot Guards. Cadogan died at his Kensington home on 17 July 1726