With the superior firepower at his disposal, British commander Henry Despard was confident his assault party would carry the day.

Whereas a steady stream of intelligence had been received before the battle of Puketutu, Despard knew little about the nature and extent of the defences at Ōhaeawai. The decisions he made that day were based on what he could observe – and the flax matting hung over the outer fence (pekerangi) blocked his view.

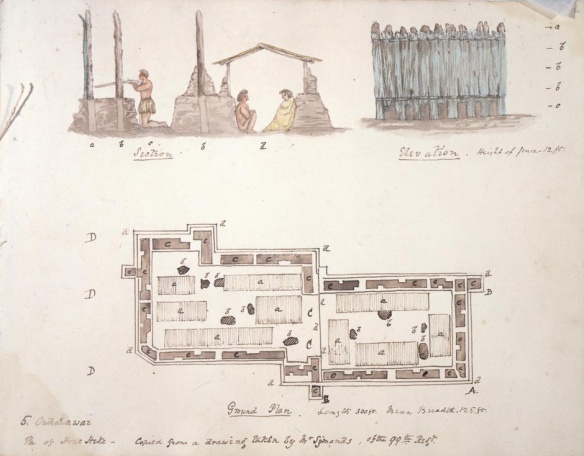

The Māori defenders could fire and reload in relative safety. The design also allowed them to fire from a variety of angles to inflict maximum damage. Ōhaeawai’s 3-m-high inner palisade was built of strong puriri logs which didn’t splinter easily. The smaller cannon made little impact on it, and insufficient 32-pounder balls were fired to cause significant damage.

Despard reported back to Auckland, anxious to pin blame for the carnage on anyone but himself, and taking with him the men of the 99th and 96th. Major Bridge was left in command of the 58th at Waimate. Back pay for all ranks was sent up to the mission station. Much of it was spent immediately on drinking and gambling by men anxious to blot out the horror and shame of Ohaeawai. Inevitably discipline grew lax. One private, a veteran who had been wounded at Puketutu, was accidentally shot dead on guard duty. The dead man, 22-year-old Private Ingate had been a Norfolk farm labourer before enlisting. His comrade Sergeant Robert Hattaway wrote: ‘He allways told us he would never Be shot by a Maorie. It was true for him. . . .’ One man was caught in the act of stealing rum from a barrel. But he was a family man and Hattaway, a newly promoted NCO, spared him a court martial. Another offender was not so lucky: an American Volunteer with a record for insubordination, he was found guilty at a drumhead court martial of cursing the British flag and immediately suffered fifty lashes.

Bridge tried to keep his men occupied by building stout earthworks and other defences around the camp as protection against an enemy elated by victory. These were almost complete when Despard returned, bubbling with his now familiar petulance. He said it was demeaning to build ramparts to defend a well-armed European force against a ‘barbarian enemy’. He ordered the earthworks flattened. Bridge held his tongue but clearly believed that the slaughter in front of Heke’s pa had taught his commander nothing.

Governor Fitzroy, anxious to get Heke to make peace, ordered the 58th withdrawn to camp among the ruins of the Kororareka settlement. His willingness to talk, and his careful conduct in the run-up to the Flagstaff War, were severely criticized in Auckland and London. He was accused of being over-protective of the interests of the aborigines and ‘losing sight of the fundamental principles, that indulgence may be abused and forebearance misconstrued’. In his own defence he later wrote: ‘Had I not treated them with consideration, and had not the public authorities been very forebearing, the destruction of Auckland and Wellington would have been matters of history before this period. An overpowering multitude have been restrained hitherto by moral influence.’ He added: ‘My object always was to avoid bringing on a trial of physical strength with those who, in that respect, were overwhelmingly our superiors; but gradually to gain the necessary influence and authority by a course of scrupulous justice, truth and benevolence.’ Such sentiments did not match the thirst for revenge and Fitzroy was recalled.

His replacement was 34-year-old Captain George Grey whose early service in Ireland had convinced him that the frontiers of the civilized world must be widened to provide fresh opportunities for the poor, landless and hungry. He had served in Australia, and on the Beagle, and had impressed his superiors with his efficiency, diligence and courage. His remit was to punish the natives, end an increasingly costly conflict and bring ‘financial and commercial prosperity’ to the settlements. He told the Legislative Council: ‘You may rely that my sole aim and object shall be to settle upon a sure and lasting basis the interests of yourselves and of your children, and to give effect to her Majesty’s wise and benevolent desire for the peace and happiness of all her Majesty’s subjects in this interesting portion of her empire, and upon which the regards of so large a portion of the civilized world are now anxiously fixed.’ He also warned the settlers that he would, if necessary, use his full powers under martial law and aim to secure in any peace the ‘freedom and safety’ to which the aborigines were also entitled.

Grey decided he must see the troubles in the North at first hand. On reaching the Bay of Islands he made some attempts to parley with Heke and Kawiti. But becoming impatient, he demanded an immediate reply to Fitzroy’s earlier peace moves. Further delays gave him the excuse to mobilize his forces. Those forces were now impressive as Grey had brought with him considerable reinforcements from Auckland. They included 563 officers and men of the 58th, 157 of the 99th, 42 Volunteers, 84 Royal Marines, a 313-strong Naval Brigade, 450 friendly Maoris – a total of just over 1,600 men plus six cannon including two 32-pounders, four mortars and two rocket tubes.

Between 7 and 11 December the British decamped and moved up the Kawakawa river to attack the ‘Bat’s Nest’ – Kawiti’s pa at Ruapekapeka, strongly built on a densely wooded hillside. Again drunkenness impeded the expedition. A few ‘old troopers’ were over-ready to blast away at anything that moved in the woods . . . wild pigs, birds and shadows. The advance faltered as bullocks, heavy carts and cannon stuck fast in the liquid mud. Christmas was celebrated by the men in teeming misery relieved only by rum. Officers noted in the diaries that the Christian natives showed great devotion in observing the day and attending mass.

By the 27th several cannon were in position overlooking the Bat’s Nest and opened fire. Despard heard worrying reports that Heke had left his own refuge and was marching with 200 men to join Kawiti at Ruapekapeka. After exasperating delays which drove Despard into deeper rages, the big 32-pounders were dragged up to join the first cannon in a formidable battery 1,200 yards from the enemy pa. The Maoris, however, were well entrenched and their defences included solid underground bunkers which resisted every shot. After each bombardment they simply emerged to repair the little damage done to the stockades. Despard later wrote: ‘The extraordinary strength of this place, particularly in its interior defences, far exceeded any idea I could have formed of it. Every hut was a complete fortress in itself, being strongly stockaded all round with heavy timbers sunk deep in the ground . . . besides having a strong embankment thrown up behind them. Each hut had also a deep excavation close to it, making it completely bomb-proof, and sufficiently large to contain several people where at night they were sheltered from both shot and shell.’

Most of the British column, including several cannon and mortars, were still on the trail. Bridge complained that the bombardment was pointless until all men and guns were in place and deployed to concentrate intensive fire on the pa’s weakest points. Instead Despard, bizarrely and to conserve ammunition, would not allow more than one cannon to be fired at any one time. Bridge wrote: ‘How deplorable it is to see such ignorance, indecision and obstinacy in a Commander who will consult no one . . . and has neither the respect nor the confidence of the troops under his command.’ He added: ‘Our shot and shell are being frittered away in this absurd manner instead of keeping up constant fire.’

The lacklustre bombardment continued until another battery was built closer to the pa, protected by 200 men. This was swiftly attacked in a sortie from the stockade and the enemy were beaten back with only light casualties on either side. The fiercest fighting was between Kawiti’s men and friendly Maoris on 2 January. In a confused and fragmented fight in thick brushland the enemy were driven back into the pa. From its barricades they taunted the white men, daring them to charge as they had done at Ohaeawai.

The siege dragged on through wet days and nights. Conditions in the British lines grew appalling. Disease and exposure put many men out of action. Reinforcements and fresh supplies were lost or abandoned on forest trails. Drunkenness continued and could not be curbed. Ammunition was wasted not just by Despard’s tactics but by jittery soldiers who saw a foe behind every bush. Men and officers who had proved themselves ready to be heroes if given the chance sank into despair at their shabby leadership.

On 8 January eighty of the enemy were spotted leaving the safety of the pa and disappearing into the forest. Governor Grey urged Kawiti by message to send away the Maori women and children as he did not want them hurt in the bombardment. The British received more reports of small bands of warriors melting away with their families. The determination of those who stayed within the pa was stiffened, however, by the arrival of Heke, although he had with him only sixty men and not the reported 200.

At last, on 10 January, the entire British arsenal was in position – the 32-pounders, smaller cannon, mortars, rockets and small arms. They opened up a ferocious crossfire on the pa’s outer defences. Despard wrote: ‘The fire was kept up with little intermission during the greater part of the day; and towards evening it was evident that the outer works . . . were nearly all giving way.’ The stockade was breached in three places. Despard was almost delirious with excitement and prepared for a frontal assault. A Maori ally, guessing his intent, shouted at him: ‘How many soldiers do you want to kill?’ Other chiefs told Grey that an attack now would result in the same waste of life as at Ohaeawai, but if they waited until the following day the enemy would have fled. Grey listened, agreed and overruled Despard, much to the colonel’s irritation.

On the following morning Waaka’s brother William and a European interpreter crept up to the stockade. They heard nothing from inside except for dogs barking. The pa seemed deserted and a signal was given to the nearest battery. A hundred men under Captain Denny advanced cautiously with native allies. Some men pushed over a section of fencing and entered the pa.

It had not been deserted. The explanation for the eerie silence was rather more strange, and rich with irony. It was a Sunday and the Christian Maoris, the majority of the defenders including Heke, had assumed that Christian soldiers would never attack on the Sabbath. Heke and the other believers had retired to a clearing just outside the far stockade to hold a prayer meeting. Only Kawiti and a handful of non-Christian warriors were left inside when the British stepped through the breach.

Too late Kawiti realized what was happening. He alerted the Maoris outside and threw up hasty barricades within the pa. He and his men managed spasmodic fire against the incoming troops. Heke and the rest of the garrison made a determined effort to re-enter the pa, firing through holes in its walls created earlier by the British cannon. Several British troops were killed and wounded but more troopers and native allies swarmed into the pa. In a topsy-turvy engagement the defenders became the attackers and vice versa within moments. Heke and the rest were pressed back to the tree-line of the surrounding forest and sheltered behind a natural barrier of fallen tree trunks.

A party of sailors, seeing action for the first time, charged this position and were shot down one by one. Three sergeants – Speight, Stevenson and Munro – and a motley band of soldiers, seamen and natives emerged from the pa and threw themselves at the makeshift barricade with such fury that the enemy withdrew deeper into the forest. The sergeants were each commended in orders and when, in 1856, the Victoria Cross was instituted Speight’s name was put forward for a retrospective citation. The award was vetoed on the grounds that no VCs could be awarded for action prior to the Crimean War.

Kawiti and his stragglers fought their way clear of the pa and joined Heke and the other fleeing warriors in the forest. The battle was over. The British had succeeded because the Christian Maoris were more scrupulous in observing the faith than the Christian Europeans. It may have been farcical but it was not a bloodless victory. Friendly Maori casualties were not recorded but the British lost 12 men killed, including 7 sailors from HMS Castor, and 30 wounded, two of whom later died. Despard claimed that the enemy’s losses were severe, including the deaths of several chiefs, but he was keen to add to the scale of the victory. He explained that a body count was not possible as the Maoris ‘invariably carry off both killed and wounded when possible’. Ruapekapeka was burnt. The First Maori War, an unconventional campaign, had ended in a suitably offbeat way.

#

Despard did not enjoy popular acclaim for the victory. He exaggerated the scale and ferocity of the final battle in his despatches, although his reference to ‘the capture of a fortress of extraordinary strength by assault, and nobly defended by a brave and determined enemy’ contains some truths. His bravado cut no ice with the colonial press who lambasted him mercilessly. An editorial in The New Zealander condemned his ‘lengthened, pompous, commendatory despatch’. Puzzled, angered and saddened by such barbs Despard left for Sydney on 21 January. Bridge noted caustically that his departure was ‘much to the satisfaction of the troops’. Despard retained command of the 99th until he was seventy but, happily for the men under him, never saw active service again. He died, a major-general, in 1858. He never, according to contemporaries, understood the ill gratitude he received. Many of his men, grieving for fallen comrades, would quite happily have hanged him.

Heke and Kawiti first tried to join up with their former ally Pomare but that wily old brigand knew which way the wind was now blowing and refused them aid. The rebel chiefs knew that the time to talk peace had now come. They opened negotiations with Governor Grey using their enemy Waaka as a go-between. Kawiti was prepared to agree peace for ever more. Heke, however, insisted that a Maori flagstaff should be erected alongside the Union Jack. Grey for his part rescinded all threats to seize Maori lands and granted free pardons to both chiefs and their men. He promised that all concerned in the rebellion ‘may now return in peace and safety to their houses; where, so long as they conduct themselves properly, they shall remain unmolested in their persons and properties’. Her Majesty, he said, had an ‘earnest desire for the happiness and welfare of her native subjects in New Zealand’.

The clemency shown by the Governor was not due to humanitarian feelings. Grey needed to bring the Northern troubles to a swift conclusion because his troops were desperately required in the South to deal with violence which had flared up around Wellington. The causes were familiar: a new clash between the land-hungry New Zealand Company and the chief Te Rangihaeata, whose earlier massacre of white men had so encouraged Heke.

The murders, sieges and inconclusive campaigning that followed in the South cannot properly be regarded as part of the Flagstaff War. Rather it was a foretaste of the bloodshed that was to follow with little let-up for another two decades. But in the North, around Auckland, the peace treaties were honoured by both sides and the occasional violent clash was small in scale.

Most of the 58th, which had done the lion’s share of the fighting, left for Australia after a riotous ball organized by the grateful ladies of Auckland. Bridge and almost every other officer in the regiment were mentioned in despatches for their bravery, although these were the days before medals for courage were awarded. Bridge, after a long wait, took command of the regiment, at the age of fifty-one. His military career after New Zealand was uneventful. He retired in 1860, broken-hearted by the death of his second wife and of all but one of his many children. He died in Cheltenham in 1885, aged seventy-eight.

Corporal Free, who had written such a vivid account of the attack and tragedy at Ohaeawai, stayed in New Zealand and served with the Rifle Volunteers. He died, aged ninety-three, in 1919. Sergeant William Speight, the hero of Ruapekapeka, may not have been awarded a Victoria Cross but years later he was granted a Meritorious Service Medal and a £10 annuity for that action; he was the only veteran of the first Maori War to receive the medal. He stayed with the 58th and retired, a staff sergeant-major, in 1858 to settle permanently in New Zealand.

In 1848 Heke, who never fully accepted British rule, caught consumption which left him defenceless against other illnesses. He died two years later at Kaikohe, aged only forty. His one consolation was that the hated British flagstaff was not re-erected in his lifetime. Kawiti was converted to Christianity. He too died young, in 1853. It is likely, although impossible to prove, that had they lived longer both chiefs would have been leaders in the uprisings that devastated New Zealand through the 1850s and 1860s. The pattern set in their initial war was repeated with rising casualties and greater atrocity on either side.

The Maoris were never truly beaten but neither could they win against the tide of colonists who flooded to their green land. By 1858 there were 60,000 incomers, a decade later 220,000. The British Government decided they now sufficiently outnumbered the natives to be able to take care of themselves and the last troops were withdrawn in 1870. The wars were over but random butchery continued in isolated glades. Overwhelming numbers and disease crippled and contained the daring Maori. But the spark of resistance did not die out. In 1928 an anonymous Maori wrote: ‘We have been beaten because the pakeha outnumber us in men. But we are not conquered or rubbed out, and not one of these pakeha can name the day we sued for peace. The most that can be said is that on such and such a date we left off fighting.’