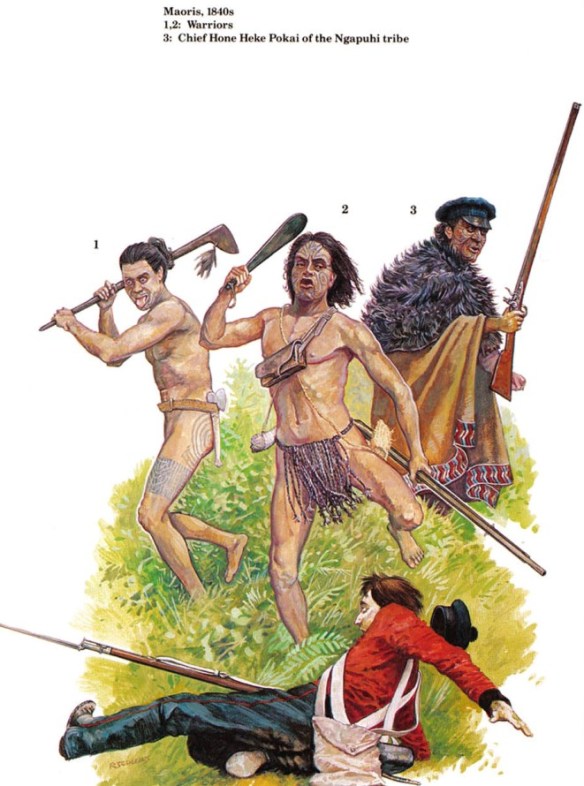

The Maori was arguably the Victorian soldier’s most formidable foe, and one he never properly beat. Yet the story of campaigns in the stinking mud and dense jungles of New Zealand, as fierce as any, is now an almost forgotten chapter in the forging of an Empire.

The first Maori War on North Island erupted four years after New Zealand became a colony. It was, absurdly, sparked by the destruction of a flagpole but there was nothing comical about the way the natives fought. The British forces expected to subdue a band of naked, undisciplined savages. Instead they faced a sophisticated warrior class, as disciplined as any Empire troops and often better equipped with more modern firearms. Instead of hit and run skirmishes and mopping up operations against defenceless villages the British repeatedly found themselves laying siege to strong, intricate fortresses complete with gun emplacements, rifle pits and bomb shelters. It was in part a throwback to medieval siege warfare, in part a foretaste of the trenches in a later, bigger war.

The British fighting men quickly recognized an equal adversary and their journals lack the sneering contempt for natives found in other colonial wars. Despite instances of cruel torture and possible cannibalism the historian Sir John Fortescue could later write: ‘The British soldier held him in the deepest respect, not resenting his own little defeats, but recognising the noble side of the Maori and forgetting his savagery.’

#

It was 800 years since the Maoris, a Polynesian people, had discovered Aotearoa, the land of the long, white cloud. In that time they had developed, through tribal disputes over land and honour, a fast and furious form of warfare. Fleet-footed warriors, armed with spears or clubs edged with razor coral, would charge straight through the enemy, striking only one blow and running on to another. The crippled enemy would be finished off by those coming behind. In a rout one man, if he were fast enough, could stab or club ten or more. To counter such raiding tactics the tribes built complex fortifications on hilltops, surrounded by ditches, palisades and banks. Over 4,000 such sites have been found in modern times, each providing evidence of communal defence and organized labour among forty tribes whose total population was somewhere between 100,000 and 300,000. The French explorer Marian du Fresne who sailed into the Bay of Islands in 1772 wrote: ‘At the extremity of every village and on the point which jutted furthest into the sea, there was a public place of accommodation for all the inhabitants.’

Captain James Cook’s 1777 journals described a fertile land of spectacular beauty inhabited by natives who, while aggressive, were intelligent and willing to trade. By the turn of the century European and American traders and whalers were using the Bay of Islands on the northern peninsula as a base. The settlement of Kororareka became a rowdy frontier town, a place of grog-shops, gambling dens and at least one brothel where pretty native girls exchanged their charms for liquor. It was known as the hell-hole of the Pacific. The Maori tribes traded extensively with the incomers and grew rich in the twin benefits of civilization – alcohol and modern firearms. The Colonial Office in London finally shook itself out of torpor and in 1840 the Union Flag was hoisted above the town, shortly before the rest of New Zealand came under the Crown.

The Maoris were – and remain – a tribal people with a strong sense of honour, of respect for the family, of a mystical sense of one-ness with their land. Children were taught that the land was sacred and that an insult must always be avenged. One proverb ran: ‘The blood of man is land.’ They were happy to trade with the white man but trouble flared when the Europeans began, slowly at first, to buy up, settle and fence off the ancient Maori homelands. More settlers flooded in. Land sharks from Sydney persuaded some chiefs to sell at rock bottom prices, creating a norm. It is a sickeningly familiar story of avaricious newcomers playing on the naive greed of individual chiefs at the expense of all.

The Colony’s new Lieutenant-Governor Captain William Hobson set out in 1840 to defuse an explosive situation. He decreed that no land could be bought from the Maoris except through the Crown. He called a meeting of the chiefs at Waitangi and proposed a treaty in which they would cede their sovereignty to the British Queen in return for guarantees that they would retain undisputed possession of their remaining lands. Among the chiefs to speak in favour was Hone Heke Pokai of the Ngaphui. He argued that the only alternative was to see their strength sapped by ‘rum sellers’. Five hundred chiefs signed the treaty.

A band of adventurers calling themselves the New Zealand Company had meanwhile established themselves near Wellington and declared that the treaty was not binding on them. After disputes over who owned what Hobson set up a land commission to investigate competing claims between the Company and the tribes. In July 1843 the Company clashed with two major chiefs, Te Rauparaha and his nephew Te Rangihaeata, over a slab of land just across the Cook Strait on South Island. Warriors harassed a survey team led by Captain Arthur Wakefield. The officer foolishly tried to arrest the two chiefs but in a confused mêlée succeeded only in shooting dead Te Rangihaeata’s wife. The enraged warriors took a terrible revenge and when the skirmish was over nineteen Englishmen and four Maoris were dead.

In the Colony’s new capital of Auckland the Governor believed that the massacre had been provoked. The settlers, however, demanded military protection and Hobson sent 150 men from the North and further reinforcements from New South Wales. The tension quickly faded and there was no more bloodshed around Wellington. The reinforcements were sent back to Australia after missionaries complained about their drunkenness and fornication.

In the Bay of Islands the slaughter of the Englishmen had a profound impact on the mind of Hone Heke. He was a renowned warrior by birth and experience, in his mid-thirties, described by one officer as ‘a fine looking man with a commanding countenance and a haughty manner’. He was not as heavily tattooed as other chiefs and had a prominent nose and a long chin. Like many of his people he was a Christian convert, having renounced youthful slaughter to train at Henry Williamson’s mission station. Although he had backed British rule at Waitangi he had since become disillusioned. The new government encouraged the whalers to find new ports and trade with the Maoris subsequently declined. Customs duties on those ships calling into port replaced the native tolls. The living standards of his people suffered. American and French traders, jealous of British annexation, told Heke that the Union Flag represented slavery for natives and he began to see the flagstaff above Kororakeke township as a sign that the British intended stealing all tribal lands. It became an obsession with him. When Heke heard of the massacre in the south he asked: ‘Is Te Rauparaha to have the honour of killing all the pakehas (white men)?’

In July 1844 he raided Kororareka to take home a Maori maiden living shamefully with a white butcher. The woman had previously been one of Heke’s servants and at a bathing party on the beach she referred to him as a ‘pig’s head’. Almost as an afterthought a sub-chief cut down the flagstaff. His bloodless action triggered a bizarre charade. A new pole was erected by the garrison, now reinforced by 170 men of the 99th Lanarkshire Regiment sent from Australia. Heke cut it down. Another replaced it, only to be chopped down a third time. The matter became a test of wills when Governor Hobson died and he was replaced by Captain Robert Fitzroy, better known now as the captain of the Beagle during the voyage of Charles Darwin. He ordered a taller and stronger pole to be erected – an old ship’s mizzen mast – defended by a stout blockhouse.

Fitzroy was particularly angered when Heke called on the United States Consul for support and later flew an American ensign from the stern of his war canoe. Between the toppling of the various poles the dangerous idiocy on both sides was almost ended several times. Heke guaranteed to replace the poles and protect British settlers. Fitzroy agreed to abolish the unpopular Customs charges which had hit Maori trade. But on the other side of the globe a House of Commons select committee chaired by Lord Howick, the future Earl Grey, decided to reinterpret the Treaty of Waitangi. They argued that the Maoris had no rights at all to the vast hinterland of unoccupied lands and urged that they should automatically fall to the Crown. The committee’s report also criticized the ‘want of vigour and decisions in the proceedings adopted towards the natives’. The implicit threat of a breached treaty was passed to the Maoris by helpful missionaries.

At dawn on 11 March 1845 Heke struck with unprecedented savagery. An officer and five men digging trenches around the blockhouse were swallowed by a flood of slashing, stabbing natives. As the troopers died the flagstaff was toppled. At the same time two columns of Maoris attacked the township below to create a diversion. Sailors and Marines guarding a naval gun on the outskirts fought hand to hand with cutlass and bayonet, pushing the attackers back into a gully before themselves being forced back with their officer severely wounded and their NCO and four men dead. Troops in another blockhouse overlooking the main road exchanged fire with the attackers, as did civilians and old soldiers manning three ship’s guns. Around 100 soldiers held the Maoris back as women and children were ferried out to the sloop Hazard and other ships anchored in the bay, including the US warship St Louis, an English whaler and Bishop Selwyn’s schooner. Heke remained on Flagstaff Hill, satisfied with his day’s work and not too anxious to press home the attack on the settlement if it meant too many casualties among his own men. Uncoordinated and half-hearted fighting continued throughout the morning, periods of eerie silence being shattered by bursts of gunfire and screams and the crackle of wooden buildings put to the torch. At 1 p.m. the garrison’s reserve magazine exploded and fire spread from house to house. The cause of the conflagration was later attributed to a spark from a workman’s pipe. Although Heke had shown no sign of attacking the township, save as diversionary tactics, the senior officer present, Naval Lieutenant Philpotts, and the local magistrate decided on a full evacuation of all able-bodied men. The remaining defenders scuttled for the ships and the safety offered by Hazard’s 100 guns.

The Maoris rampaged through the burning buildings, sparing two churches and the house of the Catholic Bishop Pompallier. When looters carried off some of the Bishop’s household goods Heke threatened to have the thieves executed. Only a 3-mile hike by the Bishop to Heke’s camp, after which he urged a pardon as enough blood had been shed, saved them. The Anglican Bishop Selwyn protested when Maoris calmly and soberly began to roll away casks of captured spirits. He said: ‘They listened patiently to my remonstances and in one instance they allowed me to turn the cock and allow the liquor to run upon the ground.’ Other clergymen who later went ashore were well treated. Six settlers who returned to rescue valued possessions were not. They were butchered on the spot. In all 19 Europeans were killed and 29 wounded. The ships took the survivors to Auckland. To the Maoris, despite the reported loss of thirty-four of their own men, the white men had been humbled and the flagstaff, symbol of their pride and greed, lay in the mud.

#

Lieutenant-Colonel William Hulme, a sensible, no-nonsense veteran of the Pindari campaigns in India, was ordered to put down Heke’s rebellion and avenge the deaths. He had under his command a small force of the 96th Regiment reinforced by a detachment of the 58th Rutlandshires, newly arrived from New South Wales: 8 officers and 204 men under Major Cyprian Bridge. Bridge was thirty-six, a literate and able commander whose journals contain a straightforward account of the frustrations and setbacks of the ensuing campaign. When they anchored in the Bay of Islands the regimental band played ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘The King of the Cannibal Islands’.

They were met by 400 friendly Maoris under Tamati Waaka Nene, a devoted ally of the British who saw Heke’s revolt as a shameful breach of the oaths sworn at Waitangi. Hulme took great pains to ensure his troops knew the difference between hostile and friendly natives and promised severe punishment for any soldier who harmed a Maori ally. Many of the soldiers were uneducated country lads who were astonished at the natives’ appearance: tall, fine-looking men, their bodies heavily tattooed, their cloaks richly decorated with feathers and pelts, their ears pierced with bone, ivory and brass. They were even more astonished to be joined by a few pakeha Maoris, white men who had ‘gone native’. These included the colourful ex-convict Jackey Marmon from Sydney who boasted about the tribal enemies he had slaughtered in battle and eaten at cannibal feasts.

The flagstaff was quickly re-erected over the smoking and deserted settlement and Hulme’s main force set off for the mouth of the Kawakawa river to deal first with Pomare, a local chieftain who had sided with Heke. The ships anchored off Pomare’s pa, or fortress, which stood on an imposing headland. Pomare was arrested under a white flag. The chief was taken aboard the White Star and persuaded to order his men to surrender their arms. The soldiers looted the empty pa, found a few rifles, and burnt it to the foundations. It was an inglorious start to the campaign but those thirsty for blood soon found it.

Hulme’s next target was Heke’s own pa at Puketutu near Lake Omapere 15 miles inland and close to the friendly Waaka’s stronghold. The infantry were augmented by seamen, Royal Marines and a three-pounder battery under Lieutenant Egerton RN. They were ferried up the Kerikeri river and then marched in good order through increasingly foul weather. Fierce and sudden downpours added to the misery.

Hulme sent some men ahead with local guides to report on Heke’s position. They found a strong fortress with three rings of palisades made musket-proof with flax leaves. The outer barricades were angled to pour crossfire on any assailant. Between each line of defence were ditches and low stone walls which offered shelter from bombardments. Maori riflemen manned ditches behind the outer palisade, their guns pointing through loopholes level with the ground.

Despite a lack of adequate artillery Hulme decided to attack the next morning and his force advanced to within 200 yards of the pa. Three storming parties were prepared. Hulme’s plan depended on a terrifying bombardment by Lieutenant Egerton’s rocket battery. The Maoris believed the rockets would chase a man until he was killed. The truth soon proved rather more laughable. Egerton’s first two rockets sailed hopelessly over the pa, carving crazy patterns in the still air. The third hit the palisades with a thunderous noise but when the smoke cleared there was virtually no damage. The remaining nine proved to be just as useless.

British troops and Waaka’s Maoris were closing with the enemy when 300 hostile natives, led by Heke’s ally Kawiti, dashed from concealment behind them, brandishing axes and double-barrelled guns. The men of the 58th turned around, fired and counter-charged with fixed bayonets. Kawiti’s men later complained bitterly that the soldiers came at them with teeth gritted and yelling unseemly and unnecessary curses. The counter-charge shattered the enemy but the rest of the British force was then hit by a sally from the pa itself. Vicious hand-to-hand fighting around the Maori breastworks eventually drove the defenders back behind their palisades.

It was stalemate. British musket fire was ineffective against the strong defences, the rockets were used up, and Hulme realized that without heavier artillery he had no hope of a breakthrough. There was more inconclusive fighting amid nearby swamps but the first real battle of the war was over, a low-score draw. The British pulled back with 14 killed and 38 wounded. Their enemy, by British accounts later disputed, lost 47 killed and 80 wounded, including Kawiti’s two sons. The Maori’s own flagstaff, carrying the Union Jack as an act of ironic derision, remained aloft above Heke’s pa. The British returned, in low spirits, to their ships.

Hulme returned to Auckland leaving Major Bridge in command. Bridge decided to attack a pa up the Waikare river rather than allow his men’s morale to sink even lower, kicking their heels in the Bay of Islands. His men barely rested, he set off with three companies of the 58th. At the river’s mouth they switched to small boats, manned by sailors, with Auckland Volunteers and friendly Maoris as guides. Bridge intended to make a surprise attack and the raid was well planned at the start. The outcome was a messy if largely bloodless shambles.

Several miles upstream the boats stuck fast on mudflats. Small bands of soldiers were disembarked among scenes of noisy confusion. Some became bogged down in the mire, while Maori allies engaged in a running fight with natives who sallied from the forewarned pa. Waaka’s men got the best of the skirmish but the enemy simply disappeared into the thick brush. The soldiers entered an empty pa and found only ‘pigs, potatoes and onions.’

The pa was destroyed and, with the river’s tidal waters high enough to float the boats off the mud, Bridge withdrew his tired and grimy force. There had been no British casualties but two of Waaka’s men were dead and seven wounded. In less careful hands Bridge’s expedition could have been a disaster. Misled by dubious guides and faulty intelligence Bridge had nevertheless behaved with calmness and common sense. Such qualities were not noticeable in the new commander of the British forces.

#

The forging of the British Empire saw its share of bone-headed bunglers. Colonel Henry Despard of the 99th is widely regarded as a prime example of that species. Despard received his first commission in 1799. His military thinking was stuck fast in the conventions of the Napoleonic era. He saw considerable action in India before taking up peacetime duties as Inspecting Officer of the Bristol recruiting district. In 1842 he took command of the 99th Lancashires, which had recently arrived in Australia. In New South Wales he outraged local civilians by snubbing a ball held in his honour, by blocking public roads around the barracks, and by having his buglers practise close to their homes. Despard insisted that his new command abandon its modern drill manuals and return to those of his younger days. The result was parade ground chaos which did not augur well for an active campaign. He was prone to apoplectic rages and rarely, if ever, listened to either advice or complaints. He had no doubts about his own abilities. Now aged sixty, it was thirty years since he had seen active service. He arrived in Auckland aboard the British Sovereign on 2 June with two companies of his regiment. Major Bridge’s journal describes his mounting frustration at the arrogance and short-sighted stubbornness of his new CO.

Despard gathered his disparate force to move on the Bay of Islands. It was the biggest display of Western armed might yet seen by fledgling New Zealand: 270 men of the 58th under Bridge, 100 of the 99th under Major E. Macpherson, 70 of Hulme’s 96th, a naval contingent of seamen and marines, 80 Auckland Volunteers led by Lieutenant Figg, to be used as pioneers and guides, all supported by four cannon – two ancient six-pounders and two twelve-pound carronades.

At Kororareka Despard was told Heke had attacked Waaka’s pa with 600 men but Waaka had beaten them off with his 150 followers. Heke had suffered a severe thigh wound. Despard decided to launch an immediate assault on Heke’s new pa at Ohaeawai, a few miles from Puketutu, despite foul winter weather which was turning tracks into quagmires.

During a miserable 12-mile march the cannon became stuck fast in the mud and the little army took shelter at the Waimate mission station. Despard was reduced to ranting fury. Waaka arrived with 250 warriors but Despard said sourly that when he wanted the help of savages he would ask for it. Luckily for him his Maori allies did not hear of the insult, and Despard must have changed his mind and the Maoris joined the British.

Most of the force stayed at the station for several days until fresh supplies were brought up. On 23 June, at 6 p.m., an advance detachment came within sight of Heke’s pa. Alert Maoris swiftly opened fire but the scrub was up to 10 feet high and the skirmish line escaped slaughter, carrying back eight wounded comrades. The enemy marksmen retired to the safety of their stockade. The main British force caught up and encamped in a native village 400 yards from the pa. Waaka and his men occupied a conical hill nearby to protect the British from a flanking attack. A breastwork and battery for the guns was swiftly erected.

Heke’s new pa was twice as strong as that at Puketutu. It was built on rising ground with ravines and dense forest on three sides, giving the defenders an easy route for supplies, reinforcements or withdrawal. There were three rows of palisades with 5-foot ditches between them. The outer stockade was 90 yards wide with projecting corners to allow concentric fire. The defenders, standing in the first inner ditch, aimed through loopholes level with the ground. The ditch was connected by tunnels to bomb shelters and the innermost defences. It was a sophisticated citadel and was well stocked. The Maoris had a plentiful supply of firearms and ammunition, some of it looted, the rest bought or bartered before the uprising. Four ship’s guns were built into the stockade.

Officers, pakeha Maoris and native allies warned Despard of the fort’s great strength. So too did Waaka. All such doubts were rebuffed. After one angry exchange Waaka was heard to mutter in his own language. Despard insisted on a translation. He was told: ‘The chief says you are a very stupid person.’

The British battery opened fire at 10 a.m. on the 24th but ‘did no execution’. The Maoris returned fire and until nightfall there was no let-up in the fusillades of shell, ball and grape. Bridge wrote that much shot burst within the pa and ‘I fancy they must have lost many men.’ The following day the bombardment continued but the flax-woven palisades made it impossible to see how much damage was done to the defences. The shot was simply absorbed by the flexible material.

Despard decided that only a night attack would breach the stockade. He prepared storming parties with ladders ready for 2 a.m. He ordered the construction of flax shields, each 12 feet by 6, to be carried by advanced parties. That night Sergeant-Major William Moir said: ‘The chances are against us coming out of this action. I look upon it as downright madness.’ Luckily for everyone concerned a storm in the early hours prevented the night attack. The following morning the flax shields were tested and to the surprise of few the shot passed clean through. After that demonstration few soldiers trusted Despard’s ability and some doubted his sanity. Another of his bright ideas involved firing ‘stench balls’ at the enemy. That also flopped.

The physical condition of the British deteriorated as rain poured incessantly on their crude shelters. Their clothing was reduced to rags, in some cases barely recognizable as uniforms. There was no meat and little flour but a gill of rum was given to each man every morning and evening. Taken on an empty stomach and supplemented by local native liquor the result could be devastating. Drunkenness, a problem throughout the New Zealand campaign, increased. There were fights over the firm-limbed and cheerful native women.

A new battery was built closer to the pa’s right flank and quickly came under hot fire which wounded several soldiers and killed a sailor. An enemy raid was beaten off but the guns were withdrawn. Despard demanded that HMS Hazard’s 32-pounder be dragged from the mouth of the Kerikeri. After a brutal and agonizing haul it was manhandled into position halfway up the conical hill by twenty-five sailors. Despard planned to attack as soon as the big gun had softened up the outer defences. He told Bridge: ‘God grant we may be successful but it is a very hazardous step and must be attended with great loss of life.’

On the morning of 1 July the enemy launched a surprise attack on Waaka’s camp on the conical hill, aimed at killing Waaka himself. A number of Heke’s men moved undetected through the forest and emerged behind the camp. Caught off guard, the native allies streamed down the hill with their women and children. Despard, who had been inspecting the cannon, was engulfed in the panic-stricken human tide. He ran into the British camp and ordered a bayonet charge up the hill. The soldiers came under crossfire from hill and pa but by then only a few of the enemy were left on the summit and it was quickly retaken. The attackers withdrew when they realized that Waaka had escaped.

Despard was driven to characteristic fury by his ignominious sprint into his own camp. His temper must have deepened with ill-concealed sniggers from the ranks of his tattered army. He decided to attack that same afternoon. The bombardment had clearly failed to leave gaping holes in the outer stockade and the enemy appeared unscathed. His troops and their Maori allies regarded a frontal assault as suicidal. But no appeals to caution would persuade him otherwise. The scene was set for tragedy.

His plan, such as it was, was to focus the attack on a narrow front at the pa’s north-west corner, which Despard believed had been damaged by the cannonfire. Twenty Volunteers under Lieutenant Jack Beatty were to creep silently to the outer stockade to test the defenders’ alertness. They were to be quickly followed by 80 grenadiers, some seamen and pioneers under Major Macpherson, equipped with axes, ropes and ladders to pull down sections of the wood and flax perimeter. Behind these were to be 100 men under Major Bridge who were expected to storm through the gaps into the pa. They in turn were to be backed by another wave of 100 men under Colonel Hulme. Despard planned to lead the remainder of his force into the stockade to mop up and accept the enemy surrender.

The Maori plan of defence was less elaborate. One unknown chief called out: ‘Stand every man firm and you will see the soldiers walk into the ovens.’

At 3 p.m. precisely on a bright and sunny afternoon the storming parties fell in. There was no surprise. They charged in four closely packed ranks, according to regulations, with just twenty-three inches between each rank. Fifty yards from the pa the men cheered. Corporal William Free later wrote: ‘The whole front of the pa flashed fire and in a moment we were in a one-sided fight – gun flashes from the foot of the stockade and from loopholes higher up, smoke half hiding the pa from us, yells and cheers and men falling all around. A man was shot in front of me and another was hit behind me. Not a single Maori could we see. They were all safely hidden in their trenches and pits, poking the muzzles of their guns under the fronts of the outer palisades. What could we do? We tore at the fence, firing through it, thrusting our bayonets in, or trying to pull a part of it down, but it was a hopeless business.’

The Maoris allowed Macpherson’s men to come within yards of the stockade before opening up with every gun they had. Their blistering fire was later described as like ‘the opening of the doors of a monster furnace’. Only a handful of men with axes and ladders reached the barrier. Despard, supported by Bridge, later claimed that the Auckland Volunteers had dropped flat at the first fusillade and would not budge thereafter. The surviving men at the foot of the stockade scrabbled hopelessly at the interwoven flax, firing at the occasional glimpse of a tattooed face within.

Bridge was no slacker and he and his men were soon caught in the same murderous fire. He wrote: ‘When I got up close to the fence and saw the way it resisted the united efforts of our brave fellows to pull it down and saw them falling thickly all around, my heart sank within me lest we should be defeated. Militia and Volunteers who carried the hatchets and ladders would not advance but laid down on their faces in the fern. Only one ladder was placed against the fence and this by an old man of the Militia.’

Despard watched the bloody shambles from the rear earthworks. Even he realized that such slaughter was worthless. A bugle call to withdraw was ignored in the heat of battle. A second call finally penetrated the brains of men conditioned to believe that retreat in the face of half-naked savages was unthinkable. The survivors dragged as many of their wounded comrades back with them as was feasible. Some soldiers returned two or three times through a hell of musket smoke and shot to rescue their mates. One wounded man was shot dead as he was carried on the back of Corporal Free, who dropped the corpse and carried another soldier to safety. Hulme’s supporting party covered the retreat well with substantial fire which kept enemy heads down. But the casualties suffered in just seven minutes of fighting were fearful. At least one-third of the British attackers had been killed or wounded. Three officers, including Beatty, were dead and three injured. Some 33 NCOs and privates were killed and 62 wounded, four of whom later died. The Maoris lost ten at most. Bridge wrote: ‘It was a heartrending sight to see the number of gallant fellows left dead on the field and to hear the groans and cries of the wounded for us not to leave them behind.’

The jubilant Maori defenders rejected a missionary’s flag of truce and during that long night held a noisy war dance. The dispirited troops huddled in their camp and mourned their dead and tended their casualties and wondered who would be next. They were tormented by the ‘most frightful screams’ from within the pa, screams which haunted all who heard them.

Two more days passed before Heke allowed the British to collect their dead from the charnel field in front of his stockade. Several corpses had been scalped, beheaded and otherwise horribly mutilated. One, that of a soldier of the 99th, bore the marks of being bound, alive, by flax. His thighs had been burnt and hacked about. A hot iron had been thrust up his anus. The soldiers knew then the source of those terrible nocturnal screams.

Despard prepared to break camp and return, beaten, to Waimate. Waaka and his chiefs, hungry for loot, persuaded him to stay a few more days at least. More shot and shell for the cannon were brought up and the bombardment of the pa resumed. It continued ceaselessly for another day. That night dogs began howling within the pa. It was a sign, according to Maori allies, that the enemy were withdrawing. The following morning, while the British slept, Waaka’s warriors slipped into the fort and found it empty. They looted everything, including weapons taken off the dead. They condescended to sell the outraged British the odd sack of potatoes. Everything else they kept for future trade. One officer missing in action, Captain Grant, was found in a shallow grave near the palisade. Flesh had been cut off his thighs, apparently for eating.

After inspecting the pa’s defences from the inside Bridge wrote: ‘This will be a lesson to us not to make too light of our enemies, and show us the folly of attempting to carry such a fortification by assault, without first making a practicable breach.’ The pa was burnt but there was no sense of victory. Heke had simply moved to build a new stronghold elsewhere, no great inconvenience. Too many lives had ended for no good reason.