Clearly North Africa was a good place to start and to exercise the growing Allied amphibious capability. Without the industrial support of Metropolitan France, resistance by Vichy forces, no matter how determined, was bound to be overcome sooner rather than later. That opposition was likely demonstrated not just by the Vichy refusal to surrender the French fleet at Mers-el-Kébir and Oran, but by the fact that in May 1941 the Vichy regime had signed the Paris protocols with Germany. These allowed the Germans to use French bases in Syria – which prompted the British-led invasion of that country – and in Tunisia and French West Africa, as well as releasing almost 7,000 French prisoners of war for service with the Free French in North Africa.

Operation Torch

Another factor in the choice of North Africa was that British and British Empire forces were already engaged in the Western Desert, in Libya and Egypt, and landings further west would help them by squeezing the Italians and Germans between two large Allied forces. The British had become increasingly successful in North Africa with the capture of El Alamein, but more was needed if the Mediterranean was to be secured. The Royal Navy and Royal Air Force had certainly helped to weaken the Axis forces in North Africa, attacking and sometimes cutting the supply lines from Italy to Libya.

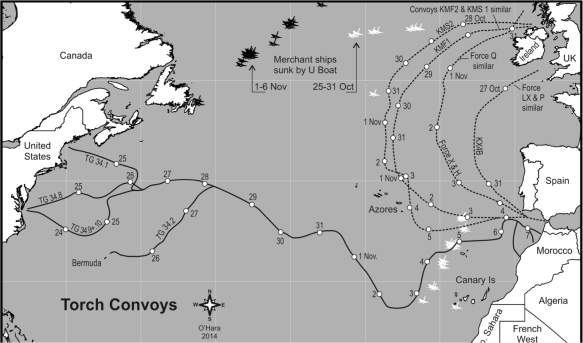

For many this was the ‘Second Front’, landing almost 100,000 men in French Morocco and Algeria behind the Axis lines. The operation, code-named TORCH, had to take into account that Morocco included Spanish-held territory to the south and east of Tangier. The Allied naval commander was Admiral Andrew Cunningham of the Royal Navy, while the Supreme Commander was General Dwight Eisenhower of the United States Army.

The division of territory in Morocco between France and Spain meant that the invasion forces had to be divided into three. The Western Task Force, designated TF34, came from the United States with twenty-three transports to land 34,000 troops commanded by Major General Patton to the north and south of Casablanca. The force had covering fire from 3 US battleships as well as the aircraft carrier USS Ranger and 4 escort carriers, 7 cruisers and 38 destroyers.

The Centre Task Force came from England and was commanded by Commodore Troubridge, RN, with 2 escort carriers, 3 cruisers and 13 destroyers escorting and then supporting 28 transports and 19 landing craft, landing 39,000 soldiers commanded by Major General Fredendall at Oran in Algeria.

Near Algiers, 33,000 British and American troops under the command of Major General Ryder were landed from 16 transports and 17 landing craft with the aircraft carriers HMS Argus and Furious (the world’s first two aircraft carriers), 3 cruisers and 16 destroyers commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Harold Burrough, RN.

Good communications are essential in any such operation but with the forces divided as they were, communications were more important than ever. Commodore Troubridge had his signals team in the exarmed merchant cruiser Large, which had been converted so hastily that the sleeping accommodation for staff officers, just aft of the bridge, was unfinished and umbrellas provided the only protection from the weather.

The landings all took place on 8 November, starting an hour or so after midnight at Oran and then shortly afterwards at Algiers, while those at Casablanca started at 04.30. Many of those involved were very inexperienced, and this told most with the pilots aboard the US ships. The escort carrier USS Santee had just 5 experienced pilots aboard and during the operation she lost 21 of her 31 aircraft, of which only one was ‘just possibly’ due to enemy action.

The invasion showed confusion among Vichy leaders. Admiral Darlan, in Oran and in overall command of Vichy French forces, agreed to a ceasefire if Marshal Philippe Pétain, the dictator of Vichy France, agreed, but Pétain was desperately trying to prevent German forces from entering unoccupied France. Darlan then decided to change sides and ordered his forces to side with the Allies, but a number of his subordinate commanders disagreed and allowed German forces to enter Tunisia.

Meanwhile, British and American ships attacked the Vichy positions with gunfire and carrier-borne air power. Several of the British Fleet Air Arm pilots were engaged in air-to-air combat with French fighters. Another was shot down by anti-aircraft fire, but while his captors decided what to do with him the Vichy French forces surrendered and he was back on board his ship within two days of being shot down. One of the shortest spells as a prisoner of war on record!

Eight months were to pass before the next Allied invasion; that on Sicily, Operation HUSKY, on 10 July 1943. The delay was necessary because Axis forces in North Africa were still capable of fighting and it took until May 1943 before resupply became completely impossible and they surrendered to the Allies.

At this stage the United States would have preferred to start planning an invasion of France, but the British saw the taking of Sicily as more important. It would not only lead to the invasion of Italy, through which Churchill hoped to reach Germany, but more importantly it would ease the pressure on Malta and also enable the Mediterranean to be used by convoys once more. The saving in fuel and time of using the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal rather than sailing via the Cape was one consideration, but another was that this provided a massive one-off boost in both merchant shipping tonnage, estimated by some to be the equivalent of having an extra 1 million tons of shipping, and naval vessels, all of which could be used to ease the pressure elsewhere.

Invading France – or as Churchill insisted, landing in France, as he believed that as allies, the UK and USA could not ‘invade’ France to liberate it – was in any case going to be the hardest of all. While the so-called ‘Atlantic Wall’ was not as well-built and defended as Hitler liked to believe, it was still a formidable obstacle and the Germans had substantial air and ground forces in the country. Even the Americans began to realize that an invasion of France would take time to prepare, with rehearsals and training. A good indication of the size of the problem was that the original idea was for simultaneous invasions of Normandy and the south of France, but the resources simply were not available.

The decision to invade Sicily was taken at the Casablanca Conference held between 14 and 24 January 1943. Code-named SYMBOL, this was one of the most important conferences of the war, planning future strategy, and was attended by the British and American leaders, Churchill and Roosevelt, as well as Generals Alexander and Eisenhower. However, there was one noticeable absentee: Stalin. The Soviet leader was invited but he declined because of the critical situation at Stalingrad. It was at Casablanca that the Allies first decided to demand unconditional surrender and also planned a combined USAAF and RAF bomber offensive against Germany. A determined effort was also made to reconcile the different factions of the French armed forces represented by de Gaulle and Giraud, and this led to them forming a French National Committee for Liberation.

Stalin’s failure to attend the Casablanca Conference was yet another instance of his lack of logic, especially since he missed the opportunity to demand an Allied invasion of France and his much-desired ‘Second Front’. The Battle of Stalingrad was almost over, the Germans having been encircled and an attempt to relieve them foiled by the Russians. While final surrender did not come until 2 February, any other leader would have had the strategic perspective and the confidence to leave matters in the hands of trusted military commanders.

Much of the problem lay in Stalin’s policy of, in modern terms, micromanaging the war. He knew who was in command and where they were situated, down to middle-ranking officers. His close colleagues, in effect his war cabinet, were constantly harassed and bullied, humiliated in front of their peers. Often a close member of their family would be held in a gulag (prison camp), usually on rations that were not even at subsistence level. There was no trust, no semblance of being part of a team, but instead the rule of fear. In short, Stalin felt vulnerable.

Operation HUSKY was more akin to the Normandy landings than TORCH had been, with a combined amphibious and airborne assault. First, on 11 and 12 June 1943, the garrisons on two small Italian islands, Pantelleria and Lampedusa to the west of Malta, surrendered after bombardment by the Royal Navy and raids from Malta-based squadrons of the RAF and Fleet Air Arm.

For some time the Royal Navy had maintained what amounted to a second Mediterranean Fleet in what was officially known as Force H, based on Gibraltar, while the Mediterranean Fleet had been forced to withdraw to Alexandria in Egypt from the beginning of 1941. Force H had grown in strength and its successes had included participation in the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck. By mid-1943 it had 6 battleships and 2 modern aircraft carriers – HMS Indomitable and Formidable – plus 6 cruisers and 24 destroyers. Designed to be a fast-moving task force, it did not have escort carriers. Force H was to act as the covering force for Operation HUSKY. The landings were by an American Western Naval Task Force and a British Eastern Naval Task Force. There were 2,590 ships altogether with 2,000 landing craft, including the new landing ship tank (LST), with the intention of landing 180,000 men under General Dwight Eisenhower who had to face more than 275,000 men in General Guzzoni’s Italian Sixth Army.

Where the Allies were strongest was in the air, as well as at sea. The Allies had 3,700 aircraft, mainly operating from land bases in North Africa as well as the three airfields on Malta, while the Axis powers had 1,400 aircraft.

The Western Naval Task Force was to land the US Seventh Army on the south coast of Sicily, while the British Eastern Naval Task Force would land the British Eighth Army on the south-eastern point of the island. The Americans had to take the port of Licata and the British the port of Syracuse. After this, they were to seize the airfields around Catania.

The assault was launched from North Africa as the forces assembled would have overwhelmed the facilities available on the small island of Malta. On the eve of the invasion, bad weather nearly caused the landings to be postponed. This did at least lull the Axis commanders into a false sense of security, apart from which many of them had been led to believe that the Allies would head for Sardinia. The result was that the amphibious assault was a great success, but in the high winds the airborne assault was less so, with many paratroops landing in the seas while many of the Horsa gliders suffered the same fate having been released too early by their towing aircraft. More than 250 troops were drowned.

On 11 July a strong counter-attack was launched by German Panzer divisions, but this was broken up by Allied air power and a heavy bombardment from Force H.

Italian resistance virtually ended when Mussolini fell from power on 25 July, after which Hitler dropped his opposition to German troops being withdrawn and some 40,000 German and 62,000 Italian troops crossed the Straits of Messina to the Italian mainland starting on the night of 11/12 August, with much of their equipment and supplies intact.

Only the invasion of Normandy, Operation OVERLORD, was larger than HUSKY. More than any other operation, the invasion of Sicily provided the Allies with vital experience and many lessons were learned that would prove invaluable later.

The logical move was for the Allies to follow the retreating Axis forces across the Straits of Messina and this is what Montgomery’s Eighth Army did on 3 September 1943. That same day, the Allies and the Italians signed a secret armistice at Syracuse.

The next step was to cut off as much of the German forces as possible and also shorten the advance towards Rome. This was done at Salerno on 9 September, the day after the armistice was announced. The landings at Salerno were co-ordinated with a British airborne landing at Taranto to enable the remains of the Italian fleet to escape to Malta. The airborne landing was covered by the guns of the six Force H battleships.

On learning of the armistice, the Germans moved quickly to seize Italian airfields. Salerno was chosen instead of a landing site further north because it was close to Allied airfields in Sicily but it was only just within range for fighter aircraft, meaning that they could spend very little time patrolling the area, usually no more than twenty minutes, and if combat occurred could not return to Sicily. The solution was to deploy aircraft carriers.

The United States Navy provided an Independence-class light carrier and four escort carriers. The Royal Navy once again deployed Force H to cover the landings with HMS Illustrious and Formidable, as well as creating an escort carrier fleet known as Force V with escort carriers HMS Attacker, Battler, Hunter and Stalker augmented by HMS Unicorn, a maintenance carrier but here, not for the last time in her career, used as an active fleet carrier with fighter sorties flown from her. Force V provided thirty Supermarine Spitfire fighters aboard each escort carrier and no fewer than sixty aboard Unicorn.

The British ships sailed from Malta as if to attack Taranto, but instead headed north to Salerno. Once off Salerno, Force V was given a ‘box’ in which to operate, flying off and recovering their aircraft. The trouble was that with so many other ships in the area, the box was too small, giving the carrier commanders great difficulty as they steamed from one end to another and then had to turn. This was nothing compared to the difficulties facing the pilots, trying to land on ships steaming close to one another and avoiding mid-air collisions. Worse still, the weather on this occasion was good, too good in fact. The Seafire needed a headwind of 25 knots over the flight deck for a safe take-off but in still air conditions the escort carriers could only provide 17 knots. Arrester wires and crash barriers had to be kept as tight as possible. Most escort carriers lacked catapults – known at the time as accelerators – and even when fitted, these hydraulically-powered aids lacked the punch of a modern steam catapult. The amphibious assault and the covering force on this occasion were much smaller, at 627 ships.

In contrast to the landings in North Africa and Sicily, the Luftwaffe mounted heavy attacks against the carriers and these were sustained until 14 September. The need for air cover meant that the carriers were asked to remain on station longer than originally planned, and their frantic racing up and down with the ‘box’ meant that fuel began to run low so they had to resort to using their reserve tanks. In addition to conventional bombing, the German response was augmented by the first use of radio-controlled glider bombs that damaged two British cruisers and the veteran battleship HMS Warspite.

The difficulties faced by the carrier pilots meant that deck landing accidents accounted for a higher loss rate than the Luftwaffe with Force V’s 180 aircraft reduced to just 30 by 14 September. Meanwhile, the Germans had organized a massive counter-attack between 12 and 14 September.

As the campaign ashore moved slowly, a further amphibious assault was planned for Anzio further up the coast. For this, shore bases near the Salerno landing site were available and carrier air support was not needed, but even in January 1944 the landings at Anzio faced strong German opposition and it took four months for the Allies to break out of their beachhead. While Salerno and Vietri were captured, they remained too close to the German front line for either to be used as ports.