When the French fleet sailed for Egypt, Napoleon had left on Malta a garrison of 3,000 men under the command of General Claude-Henri Belgrand de Vaubois. The French administration had continued the unpopular reorganisation of the churches and convents, removing many of the art treasures into their own safe keeping. But Vaubois’ position was growing more difficult almost daily.

Following the defeat of the French fleet at the Nile and the arrival of Villeneuve’s ships, the garrison on Malta numbered up to 6,000 men, with two frigates and one line of battle ship,1 but the French were effectively cut off from regular supplies by a naval blockade by British ships and the refusal by the emboldened King of Naples to continue selling produce from his dominions to the French garrison on the island. However, starving the French into submission would take some considerable time, given the huge grain silos built by the Knights of St John in the solid rock, which held enough reserves for the island to survive for a year or two.

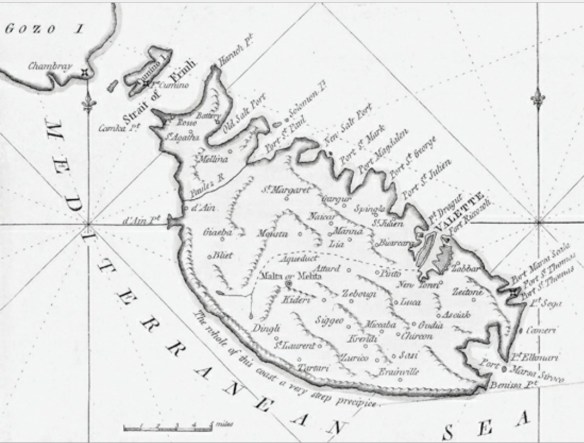

The growing disquiet within the civilian population eventually escalated into violence during a particularly bloody incident on 2 September, when the French garrison of the town of Notabile attempted to seize a convent in preparation for it to be dismantled. The angry crowd armed themselves with simple farm implements and took control of the town, overrunning the small French garrison in the process and massacring them. Vaubois promptly concentrated his troops within Valetta and a fort on the island of Gozo and waited, more in hope than expectation, for a relief force to come to his aid. The rebel movement grew quickly, spreading across the entire island like wildfire and a junta was soon formed, led by Emmanuel Vitale and Canon Francesco Caruana, who immediately appealed for help to the King of Naples for troops to support their cause. The King, however, avoided openly supporting the revolt, with French troops in upper Italy threatening his mainland possessions. However, Nelson sent a Portuguese squadron under Admiral the Marquis de Nizza, which arrived on 18 September and landed supplies and arms for the rebels. He was also ordered to continue the naval blockade, but at that moment Nelson’s only real aim was the destruction of the ships in Valetta harbour.

Captain Sir James Saumarez arrived off Malta on 24 September with part of Nelson’s battered fleet with their prizes in tow. Nelson and the remainder of his fleet arrived soon after, although the admiral himself hastily proceeded on to Naples to continue his infatuation with Lady Emma Hamilton, leaving his captains to get on with the blockade. Saumarez supplied 1,200 muskets and ammunition to the rebels and then left for Sicily to get the ships repaired.

Captain Sir Alexander Ball, commanding HMS Alexander, arrived with Culloden and Colossus to join the Portuguese ships blockading Malta. Nelson returned briefly on 24 October, landing twenty-four barrels of gunpowder and on the 28th the small island of Gozo, with its French garrison of 200 men and twenty-four cannon, fell into allied hands. Ball was installed as President of the Council to liaise with the ill trained and poorly armed Maltese and to help them maintain the blockade. To maintain their hold on their positions on shore, he bolstered their numbers by landing some 500 Portuguese and British marines. In late December three British bomb vessels arrived and a regular bombardment began; two Neapolitan frigates also arrived to bolster the blockade.

In early 1799 two French attempts to break through the naval blockade were successful, with a schooner arriving from Ancona and the frigate Boudeuse successfully delivering supplies to the island from Toulon, extending the siege by a further six months. However, food was so short that Vaubois forcibly evicted most of the civilians from Valetta, reducing the city’s population from 45,000 souls in 1799 to 9,000 the following year.4 These additional mouths simply added to the difficulties the British were having in providing supplies, particularly wheat, to the civilian population of rebel-held Malta. By April many hundreds were on the brink of starvation and Captain Ball was finding it difficult to keep the rebels at their posts. Despite frequent appeals to the King of Sicily, supplies were only grudgingly released and the navy was forced to seize passing grain ships to meet the demand.

In May news arrived of a sizeable French expedition entering the Mediterranean. Commanded by Admiral Etienne Eustache Bruix, it comprised twenty-five ships of the line from the Brest fleet and had been sent to relieve the sieges of Malta and Corfu, unaware that the latter was already in Russian hands, and to resupply the French army in Egypt. Having failed to add the five Spanish ships at Ferrol to his numbers, Bruix ignored Admiral George Elphinstone, Lord Keith’s squadron of fifteen ships of the line off Cadiz, despite his huge numerical advantage, determined to achieve his objectives. Unable to combine with the Spanish fleet at Cadiz because of adverse winds, Bruix sailed on into the Mediterranean and headed for Toulon for repairs to his storm-damaged ships.

Keith chased after Bruix, calling for every available ship to rendezvous with him, causing Nelson to lift the naval blockade of Malta to strengthen his squadron off Sicily. During the two months that Captain Ball and his ships were away, the siege was commanded by Lieutenant John Vivion of the Royal Artillery, who incredibly not only kept the siege guns firing but also managed to keep the absence of Ball’s squadron a complete secret, whilst also placating the islanders, who were again desperately short of both supplies and hope.

The British fleet, now numbering twenty ships of the line and commanded by Admiral John Jervis, Earl St Vincent, pursued Bruix towards Toulon, but soon discovered that they were being followed by seventeen ships of the Spanish fleet which had escaped from Cadiz, under Admiral Don Jose de Mazarredo, also now in the Mediterranean. The British were potentially at risk of being overwhelmed by a vast combined Franco/Spanish fleet of forty-two ships. Luckily for St Vincent, a storm wrought havoc on the Spanish fleet particularly, no fewer than nine ships being virtually dismasted, and the whole fleet was left in such poor condition that the Spanish were forced to run for the safety of Cartagena.

Whilst St Vincent watched the Spanish fleet at Cartagena, Bruix sailed from Toulon on 27 May with twenty-two ships of the line, leaving some badly damaged ships to continue their repairs, and accompanied a large number of supply ships full of stores and men en route to Genoa to reinforce the struggling French forces fighting the Austrians in northern Italy. St Vincent, although forced by ill health to relinquish his command to Admiral Keith, insisted on maintaining his fleet in the vicinity of his newly acquired but extremely vulnerable base on Minorca. His advance squadron did, however, have the good fortune to fall on a squadron of five French frigates under Rear Admiral Perree returning from the Army of Egypt at Jaffa to Toulon, capturing them all.

Bruix sailed from northern Italy to return to Toulon, paying a visit en route to Cartagena, where he found most of the Spanish ships were now repaired and ready for sea. Transporting 5,000 Spanish troops as reinforcements for the island of Mallorca, the combined fleet, now numbering some thirty-nine ships, sailed on 24 June for Cadiz.

On 7 July Keith’s fleet was substantially reinforced by the arrival of twelve ships under Rear Admirals Charles Cotton and Cuthbert Collingwood, which had been detached from the Channel Fleet and sent in pursuit of Bruix. Keith sailed for the Straits of Gibraltar, only to find that the enemy combined fleet had passed through some three weeks before and eventually returned to Brest, forty-seven ships of the line strong – where it then lay uselessly for over two years.

So many ships, so much effort by all sides – and so little achieved. In fact, the overall result was that although the British fleets had been led a merry dance and had clearly been outmanoeuvred, Bruix had comprehensively failed to use his superiority to achieve anything of real value. His excursion to Genoa could just as easily have been achieved by a squadron of frigates; he failed to resupply Malta and Egypt; and by sailing into the Atlantic, taking with him the Spanish fleet of Cartagena and Cadiz, simply for all of them to be bottled up in Brest, he relieved the British navy of the threat of any significant enemy ships in that sea and effectively handed control of the Mediterranean to the British.

However, the position for the allies was also complicated by Malta’s confused politics. Britain, Russia and Naples, all allies in the coalition against France, each cast avaricious eyes over Malta and it was far from clear who should act as the island’s guardian when – rather than if – the French garrison was finally forced to capitulate. Tsar Paul, as their official protector and almost certainly their next Grand Master, not unsurprisingly continued to champion the Knights of St John. His recent alliance with the Ottoman Empire had seen Russia gain the strategically important island of Corfu and a Russian fleet had entered the Mediterranean. Malta would make an excellent additional strategic point from which to build Russia’s military strength in southern Europe. Naples and Britain, however, both saw that the rule of the Knights had permanently ended, as the civilian population would never freely accept them back and they had no intention of re-imposing them with military might.

Despite this apparent disarray in the allied position over Malta, in late 1799, when the Tsar suddenly decided to withdraw from the Mediterranean, the British acted. Brigadier General Sir Thomas Graham was sent in command of a force comprising 1,300 British infantry and a similar number of Neapolitan troops to support the rebels besieging Valetta as the blockade now began to see the visible effects of starvation and disease within the garrison. On 10 February 1800 a further French relief convoy of five ships sailed from Toulon under the command of Admiral Jean Baptiste Perree in the 74-gun Genereux, a survivor from the Battle of Aboukir, in a desperate attempt to resupply the garrison. The convoy was, however, cornered off Lampedusa on 18 February and destroyed, Perree being killed during the action.

The garrison now began to see defeat as inevitable, and the 80-gun Guillaume Tell, which had also survived the Battle of Aboukir and escaped to Malta with two frigates in September 1798, was made ready to sail in a desperate attempt to escape to Toulon. Crammed with troops and commanded by Rear Admiral Denis Decres, the ship would escape during the hours of darkness and slip through the blockade before dawn. She sailed on 30 March but was immediately spotted by the frigate HMS Penelope, which constantly harried the French battleship despite being heavily outgunned; the rigging of the Guillaume Tell was seriously damaged, whilst Penelope skilfully remained out of range of her overwhelming broadside. The damage caused by Penelope meant that two British battleships, the Foudroyant and Lion, were eventually able to catch and capture the French ship despite a very determined defence.

Food shortages within Valetta led to extortionate prices for what few supplies were still available; it is recorded that eggs sold for 10 pence each; rats were 1 shilling 8 pence each and rabbits went for 10 shillings. Eventually, after a sixteen-month siege and two years of naval blockade, the French had even run out of horse, cat and dog meat and were now losing 100 men a day to starvation and disease. The frigate Boudeuse was broken up to provide firewood, but on 24 August the frigates Diane and Justice, both with understrength crews, made a desperate break for it. They were quickly spotted and pursued. Diane proved too slow and was soon captured, but Captain Jean Villeneuve’s Justice successfully outran her pursuers and reached Toulon in safety, the only ship to successfully break the blockade. The French garrison was finally forced to surrender on 4 September 1800. The terms of the surrender handed everything over to the British, not the Maltese, whom the French refused to deal with. The handover included two Maltese ships of the line and a frigate which still lay in the harbour.

In an astute and very devious move, just days before the French garrison capitulated Napoleon offered Malta to the Tsar in a clear attempt to cause disunity between the allies, but Britain was to maintain possession of the island. Its strategic position was now clear to both the British government and the Royal Navy. Situated some 60 miles south of Sicily and 200 miles from the North African coast, with an excellent deep water harbour and exceedingly strong defences, the island was in a perfect position to grant a naval power like Britain control of access between the western and eastern Mediterranean. British control of Malta would additionally make the resupply of men and equipment for the French army in Egypt extremely hazardous.

The island was made a free port and the Maltese did well under British rule because of the greatly increased trade. The island immediately became a lynchpin of British policy; it became essential to control this island fortress and it became the headquarters of the British forces in the Mediterranean and would continue as such for the remainder of the war; indeed, it would retain this vital position for the next 160 years.