In mid-March a force of fifteen hundred Canadians, French, and Indians under the command of the governor-general’s wiry, sawed-off younger brother, François-Pierre Rigaud, had approached the fort over the frozen lake and harassed its small winter garrison for four days. The raiders had come equipped only with scaling ladders, not cannon, and therefore stood little chance of actually seizing the fort unless they could surprise or stampede its commander. As it happened, Fort William Henry that winter was under the highly competent command of the man who had designed it, Major William Eyre; and Eyre made no mistakes in directing its defense. Before the raiders withdrew to Ticonderoga, however, they burned all of the fort’s outbuildings (including a palisaded barracks, several storehouses, a sawmill, and a hospital), its exposed bateaux, and the half-built sloop that stood on stocks near the lake.

Although its defenders had suffered only a handful of minor casualties and its wood-and-earth walls had been untouched by anything heavier than musket balls, the damage to Fort William Henry as a strategic outpost had been grave. The valuable supplies that would have to be replaced from Albany and the external buildings that would take weeks to rebuild were the least consequential losses. More serious by far was the loss of the fort’s bateaux, without which troops could not be moved down the lake against Fort Carillon; but most damaging of all was the loss of the sloop, which left the fort with only one serviceable gunboat to launch in the spring. As the winter’s experience showed, Fort William Henry was safe from attackers who lacked artillery. Unless the British could dominate Lake George with armed vessels, however, they could not prevent an invading French army from bringing siege cannon from Fort Carillon. It would take weeks of labor, once shipwrights had been brought in from New England, to construct a replacement for the lost sloop. In the meantime, Fort William Henry would be vulnerable to any siege the marquis de Montcalm cared to mount.

There was one other critical way in which Rigaud’s raid had put the British in New York at a disadvantage: the loss of intelligence. At the beginning of the winter Eyre’s garrison at Fort William Henry had included about a hundred rangers under Captain Robert Rogers. But Rogers had led them on a disastrous scout against Fort Carillon in January that had cost nearly a quarter of that number, and he had sustained a wound of his own that required treatment at Albany. He would not recover and return to the fort until the middle of April. Given these circumstances the rangers could not have ventured far from the fort even if conditions had favored them. But following Rigaud’s raid, the woods around Lake George grew thick with French-allied Indians. Word of Rogers’s defeat and of Rigaud’s adventure brought hundreds of Ottawa, Potawatomi, Abenaki, and Caughnawaga warriors to Fort St. Frédéric and Fort Carillon in the spring of 1757. From April through June, under the leadership of their own chiefs and of Canadian officers like Charles Langlade (who had directed the destruction of Pickawillany in 1752 and helped defeat Braddock in 1755), they raided English outposts and ambushed supply trains in the woods between Fort Edward and Fort William Henry. So effectively did the Indians and Canadian irregulars confine the rangers to the vicinity of the British forts that General Webb and his senior officers were deprived of virtually all intelligence concerning French preparations for the coming campaigns. If they had known what was coming Webb and his subordinates might conceivably have prepared more vigorously for the summer, but as late as the beginning of June the garrison at Fort William Henry had not undertaken repairs.

What Webb and his officers did not know was that since late in the summer of 1756 the most successful recruiting drive in the history of New France had been under way among the Indians of the pays d’en haut, the upper Great Lakes basin. The combination of Governor-General Vaudreuil’s enthusiasm for using Indian allies and the widespread reports of French victories at the Monongahela and Oswego attracted warriors from a vast area to serve in the principal campaign planned for 1757: a thrust against Fort William Henry. Montcalm, still unhappy with the uncontrollable behavior of his Abenaki, Caughnawaga, Nipissing, Menominee, and Ojibwa warriors after the surrender of Oswego, entertained more reservations than ever about relying on Indians, but these were overborne by the sheer numbers who presented themselves at Montréal and the Lake Champlain forts between the fall of 1756 and the early summer of 1757. Stories that the Ojibwas and Menominees carried back home to the Great Lakes after the fall of Oswego had “made a great impression,” Montcalm’s aide-de-camp noted; “especially what they have heard tell of everyone there swimming in brandy.” Of equal importance, perhaps, was the news that Montcalm had been willing to ransom English prisoners from their Indian captors after the battle. At any rate, the Indians came in numbers that exceeded even Vaudreuil’s fondest hopes and included warriors who had traveled as far as fifteen hundred miles to join the expedition.

By the end of July nearly 2,000 Indians were assembled at Fort Carillon in aid of the army of 6,000 French regulars, troupes de la marine, and Canadian militiamen that Montcalm was preparing to lead against Fort William Henry. More than 300 Ottawas had come from the upper Lake Michigan country; nearly as many Ojibwas (Chippewas and Mississaugas) from the shores of Lake Superior; more than 100 Menominees and almost as many Potawatamis from lower Michigan; about 50 Winnebagos from Wisconsin; Sauk and Fox warriors from even farther west; a few Miamis and Delawares from the Ohio Country; and even 10 Iowa warriors, representing a nation that had never been seen in Canada before. In all, 979 Indians from the pays d’en haut and the middle west joined the 820 Catholic Indians recruited from missions that extended from the Atlantic to the Great Lakes—Nipissings, Ottawas, Abenakis, Caughnawagas, Huron-Petuns, Malecites, and Micmacs. With no fewer than thirty-three nations, as many languages, and widely varying levels of familiarity with European culture represented, problems of control were magnified even beyond their usual scope. Since Montcalm realized that “in the midst of the woods of America one can no more do without them than without cavalry in open country,” he did what he could to accommodate, appease, and flatter his allies. But as he knew better than anyone else, he could not command them. Montcalm could only rely on the persuasive abilities of the missionary fathers, interpreter-traders, and warrior-officers like Langlade whom he “attached” to each group in the hope of gaining its cooperation.

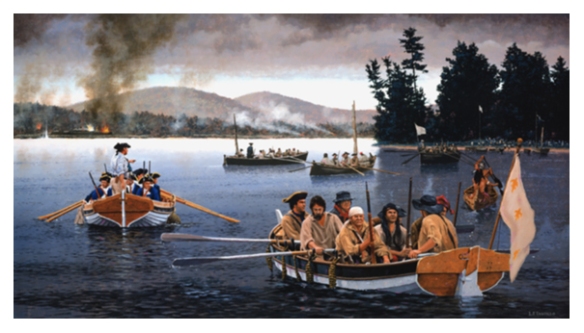

In the spring Lieutenant Colonel George Monro had brought five companies of his regiment, the 35th Foot, to Fort William Henry to relieve Major Eyre’s winter garrison. Together with two New York independent companies and nearly eight hundred provincials from New Jersey and New Hampshire, Monro’s command numbered more than fifteen hundred men in late June when two escaped English prisoners brought the first reliable intelligence of the eight-thousand-man force that Montcalm was gathering at Fort Carillon. Monro—“an old Officer but [one] who never ha[d] served” in the field—dispatched several ranger patrols over the next several weeks to observe the French and Indian buildup at the foot of the lake. None succeeded, and the lack of serviceable boats prevented Monro from mounting a reconnaissance-in-force until late July. It was only on the twenty-third that he finally hazarded five companies of New Jersey provincials under Colonel John Parker in a raid intended to burn the French sawmills at the foot of the lake and to take as many prisoners as possible. Traveling in two bay boats under sail and twenty whaleboats—virtually all of the vessels available at Fort William Henry—Parker’s command made its way north down the lake toward Sabbath-Day Point. They did not know until the next morning that more than five hundred Ottawas, Ojibwas, Potawatomis, Menominees, and Canadians were waiting for them. According to Louis Antoine de Bougainville, Moncalm’s aide-de-camp,

At daybreak three of [the English] barges fell into our ambush without a shot fired. Three others that followed at a little distance met the same fate. The [remaining] sixteen advanced in order. The Indians who were on shore fired at them and made them fall back. When they saw them do this they jumped into their canoes, pursued the enemy, hit them, and sank or captured all but two which escaped. They brought back nearly two hundred prisoners. The rest were drowned. The Indians jumped into the water and speared them like fish. . . . We had only one man slightly wounded. The English, terrified by the shooting, the sight, the cries, and the agility of these monsters, surrendered almost without firing a shot. The rum which was in the barges and which the Indians immediately drank caused them to commit great cruelties. They put in the pot and ate three prisoners, and perhaps others were so treated. All have become slaves unless they are ransomed. A horrible spectacle to European eyes.

In fact, four of the boats escaped the trap, but three-quarters of the Jersey Blues on the expedition were killed or captured. The arrival of the panic-stricken survivors offered the first tangible evidence of a large enemy presence at Fort Carillon, and it thoroughly rattled General Webb, who was making his first visit to Fort William Henry when the remnants of Parker’s command appeared. Webb ordered Monro to quarter the garrison’s regulars within the fort and directed him to have the provincials construct an entrenched camp on Titcomb’s Mount, a rocky rise about 750 yards southeast of the fort, to prevent the enemy from siting cannon on its summit. Then, promising to send reinforcements, he beat a hasty retreat to Fort Edward.