Air Vice Marshal Maynard said at the beginning of February 1941: ‘They don’t like us.’ The Germans were certainly throwing as many aircraft as possible at the island in an attempt to subdue the defenders. Day and night there were large scale raids and attempts to lay mines in the waters around the Grand Harbour.

The first major air raid of the month was launched on 4 February. Upwards of 100 enemy aircraft struck against Hal Far, Luqa and Kalafrana. Whenever possible the Germans and the Italians were still dropping their parachute mines and although a system of mine watching and sweeping was brought in, many of the mines struck the sides of the dockyards, cratering and blasting the area. If anything, the air war above Malta was beginning to intensify.

On 8 February half a dozen Hurricanes were scrambled to intercept the night raiders. A Hurricane chanced on an HE111, flying at about 10,000 ft above Rabat. The German aircraft crashed into the sea. The following day Me109s of 7 Staffel (Jagdgeschwader 26) arrived in Sicily. Most of the pilots were very experienced, having fought in the battle of Britain in the previous year. The Luftwaffe was clearly attempting to achieve air superiority and this would only add pressure to the dwindling numbers of Hurricanes and their pilots.

Three days later the Me109s appeared in the skies over the island of Malta. At the same time Hurricanes belonging to B Flight No. 126 Squadron scrambled to intercept a trio of Ju88s, reported to be flying at 20,000 ft. As the Hurricanes climbed to intercept they were pounced on by the Me109s. Pilot Officer D J Thacker’s aircraft was badly hit and lost height. He managed to get over St Paul’s Bay at around 5,000 ft, when suddenly the Hurricane’s engine cut and he was forced to bale out. He was only in the water for around three quarters of an hour before HSL107 picked him up. Two other Hurricanes were also roughly dealt with by the Me109s. Flight Lieutenant Gerald Watson lost his life when his Hurricane flipped over as he hit the sea. His body was never found. Flight Lieutenant Bradbury was more fortunate: he managed to coax his badly shot-up Hurricane back to the airfield, where he managed to make a forced landing.

It was clear that the Hurricanes were no match for the Me109s. On 16 February the experience of an encounter between the Hurricane Mark Is and the Me109s was described in a combat report written by Flight Lieutenant MacLachlan:

While on patrol over Luqa at 20,000 ft, we were attacked from above and astern by six Me109s. As previously arranged the flight broke away to the right and formed a defensive circle. As I took my place in the circle I saw four more Me109s coming down out of the sun. Just as they came within range I turned back towards them and they all overshot me without firing. I looked very carefully but could see no more enemy aircraft above me, so I turned back to the tail of the nearest 109. I was turning well inside him and was just about to open fire when I was hit in the left arm by a cannon shell. My dashboard was completely smashed, so I baled out and landed safely by parachute.

MacLachlan lost his arm when it had to be amputated at Imtarfa Military Hospital. The loss of his arm did not prevent the Flight Lieutenant from getting back into a Hurricane. Soon after his recovery from the amputation a colleague took him up for a test flight: he managed to land the aircraft by himself. A few days later he flew a Hurricane and then asked whether he could rejoin the squadron. Ultimately he was returned to Britain, where he did indeed continue to fly with great success.

There were continual raids through the first and second week of February 1941 and 17 February saw the island being raided for the eleventh night in succession. The Germans had so far failed to prevent the British from continuing to use the harbour and the airfields were still operational.

The island suffered a succession of alerts on 25 February, during which two German bombers were shot down. In the afternoon Canadian Pilot Officer John Walsh was on patrol over the island. He was attacked whilst he was flying at around 27,000 ft, over St Paul’s Bay. He was forced to bale out, but managed to land a few hundred metres from a naval vessel. One of Walsh’s legs had been broken in four places and he also had a broken arm. It was likely that he had hit his own tail plane when he baled out. Unfortunately Walsh died of pneumonia.

On 26 February one of the biggest raids on the island so far was launched. Around thirty-eight Ju87s, twelve Ju88s, ten Dorniers and ten HE111s were escorted by up to thirty enemy fighters. They seemed to be making for Luqa as their primary target when they were spotted at around 13.00 hours. Anti-aircraft defences opened up on them and eight Hurricanes took off to intercept. However, the main force of bombers passing over the island at between 6,000 and 8,000ft covered Luqa airfield in bombs. Half a dozen Wellingtons were burned out and seven more were badly damaged. There was also damage to some Marylands that were parked on the airfield. The airfield itself was badly cratered, with severe damage to hangars and workshops and would be out of service for 48 hours. The anti-aircraft crews claimed five of the Ju87 dive bombers, with four probable and one damaged. The Hurricanes had two confirmed kills and eleven probable. However, the RAF losses for the day were five Hurricanes, and three pilots were lost.

This was not the end of the action for the day: two German airmen from a Ju87 were picked up by an Air Sea Rescue launch HSL107. The men had been hanging onto a lifebuoy. An Me109 also attacked a pair of fishing boats off Gozo. Later in the afternoon, a Red Cross seaplane was spotted, escorted by German aircraft, hunting downed crew members. The Germans attempted another major attack later, with dive bombers coming in, dodging the bursting shells of the anti-aircraft batteries.

With the losses on the ground and in the air, it was becoming clear that the Germans were slowly gaining air superiority. The larger formations appearing over the island showed that they were prepared to be bolder than the Italians had been in the past. Systematically they were attempting to neutralise Malta’s fighter defences and to cause long-term damage to the airfields. In the course of ten days in February, all the Royal Air Force’s flight leaders had been lost. Throughout the month of February there had been at least 109 air alerts, sixty-two of which had developed into raids. The Germans were being extremely selective, striking primarily at Hal Far, Luqa and the dockyards. Of the 376 tons of bombs dropped on the island, all but two tons had landed on these targets.

Malta’s shrinking air resources were a major problem and would become even more so as the German air offensive intensified. A signal from Malta at the beginning of March outlined the danger the island now faced:

Blitz raid of several formations totalling certainly no less than one hundred aircraft, of which sixty bombers attacked Hal Far. A few of these aircraft dropped bombs and machine gunned Kalafrana. Damage to Kalafrana was slight both to buildings and aircraft. One Sunderland unserviceable for few days. Damage Hal Far still being assessed. Preliminary report as follows: three Swordfish and one Gladiator burnt out. All other aircraft temporarily unserviceable. All barrack blocks unserviceable and one demolished. Water and power cut off. Hangars considerably damaged. Airfield temporarily unserviceable. Eleven fighters up. Enemy casualties by our fighters, two Ju88s, two Ju87s, one Do215, two Me109s, confirmed. One Ju88 and three Ju87s damaged. By AA one Me110 and eight other aircraft confirmed, also four damaged. There are probably others which did not reach their base but cannot be checked. One Hurricane and one pilot lost after first shooting down one Ju87 included above. For this blitz every serviceable Hurricane and every available pilot was put up and they achieved results against extremely heavy odds. The only answer to this kind of thing is obviously more fighters and these must somehow be provided if the air defence of Malta is to be maintained.

The signal almost certainly related to the massive raid that the Germans launched on 5 March, when upwards of sixty bombers, escorted by Me109s, dropped bombs across the island. At least two German aircraft, a Ju88 and a Ju87, were definitely shot down. Two days before Carmel Camilleri, a Maltese police constable, was awarded the George Medal for his actions that had taken place on 4 November 1940. The gallantry award read:

In the early morning of 4 November 1940, a Royal Air Force aircraft crashed on a house at Qormi, and the front portion of the machine fell into a 40 ft shaft at the bottom of a deep quarry beyond the house. Moans were heard coming from the shaft, from which flames were spouting, and an injured airman was observed supporting himself under the vertical edge of the shaft. A wire rope was lowered which the airman grasped, but after being drawn up a few feet he could not maintain his hold and fell back into the shaft. PC Camilleri, who had been one of the first on the scene, immediately volunteered to go down for him, in spite of the flames from the burning aircraft and in disregard of danger from the possible explosion of heavy calibre bombs, and was lowered into the shaft. The rope slipped and he fell to the bottom, fortunately without serious injury. A third rope was lowered to which PC Camilleri tied the injured airman who was then hauled up. The rope was again lowered for Camilleri, who was brought up with no injuries beyond slight burns.

On 6 March, whilst German bombers carried out a number of attacks, and enemy fighters struck flying boat bases, five Hurricanes, led by a pair of Wellingtons, arrived from Egypt as reinforcements for the island. The following day Sergeant Jessop was attacked by an Me109 on his first flight around the island. He was picked up by HSL107. Me109s also made strafing attacks at St Paul’s Bay, hitting a Sunderland flying boat. Sergeant Alan Jones, firing a Vickers machine gun, tried to beat the fighters off, but was shot and killed.

Me110s returned once again to shoot up St Paul’s Bay on 10 March. They hit the same Sunderland, this time setting it on fire. The crew could not get the blaze under control and the flying boat was towed into Mistra Bay, where it eventually sank. At night large numbers of German aircraft dropped bombs and at least one was shot down by anti-aircraft fire. The Germans targeted Sliema on 11 March, killing a number of civilians and on 15 March German bombers hit the airfield once more. A mine exploded in the main harbour, killing three and wounding ten others. There were also bombing casualties in Gozo.

On 18 March half a dozen Hurricanes, led by a Wellington, arrived from Libya to replace casualties that had been inflicted on the fighter squadrons in the past few weeks. There was a brief lull in operations until 22 March, when ten Ju88s, escorted by a number of Me109s, raided the island in the afternoon. It was a particularly bad day for the RAF, as five Hurricanes were shot down, four of which hit the sea, all four pilots were drowned. There were further night attacks and reports at the same time suggested that up to twelve enemy aircraft had been claimed by anti-aircraft fire.

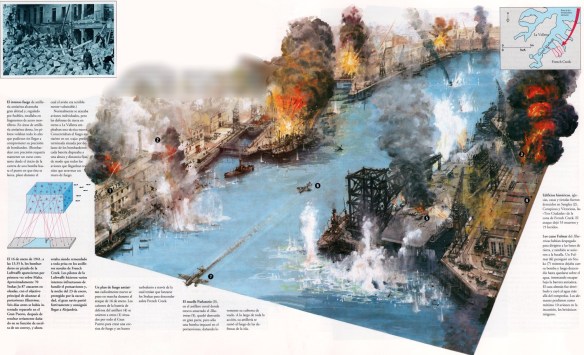

On 23 March a convoy reached Malta from Haifa, bringing supplies and reinforcements into the Grand Harbour. It proved to be a tempting target for the Luftwaffe. An air raid developed at 13.35, when thirty Ju87s, escorted by twenty Me109s, attacked the ships. Fourteen Hurricanes were sent up to intercept. They managed to shoot down nine dive bombers, anti-aircraft fire claimed another four. The cargo ships were the City of Lincoln, City of Manchester, Clan Ferguson and Perthshire. Three of them were slightly damaged in the air-raid attack, as were a cruiser and destroyer that were escorting them. The Germans tried again to sink some of the convoy ships in the Grand Harbour on Monday 24 March when there was an evening attack by Ju88s with accompanying Me109s.

On the night of 25 March a Sunderland flying boat left Cairo bound for Malta. Onboard was the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir John Dill, the Chief of Radar Development, Robert Watson Watt, Admiral Lyster of the Fleet Air Arm and two American senior servicemen. They were making the journey from Egypt via Malta and Gibraltar to England. One of the crew members recalled the flight:

We had taken off from the Nile at Cairo in late afternoon sunshine and as darkness closed in we received the first message from Air HQ Malta, which warned of bad weather conditions and advised caution on landing there. This was soon followed by a second message stating sea conditions as very bad, also ten-tenths cloud cover over the island. From a fuel situation we were passed the point of no return, so we could only go on; it was Malta or nowhere. AHQ Malta had decided to beam one searchlight vertically to assist our approach. Our navigator was on top form and after a flight of about 900 miles he was spot on, almost straight ahead a patch of illuminated cloud layer indicated the searchlight position. Our very experienced captain brought the aircraft down through the cloud cover and made a good approach run. The very bad conditions prevailing in Marsaxlokk Bay made it impossible to use the normal flare path of marker buoys, so two launches with searchlights were positioned to guide us in. Our landing lights revealed a frothing, heaving sea beneath, as we hurtled in through the darkness for the touch down. There was an almighty bounce, then a series of smaller ones and finally that sturdy hull settled down into the angry sea. After finding a buoy, mooring up and with engines shut down, hearing the howling wind and the crashing waves made us all realise what a terrific landing the pilot had pulled off. Then he later admitted to us that after the first bounce ‘it was in the lap of the Gods’. Our passengers seemed unperturbed and Sir Anthony made a little joke about the landing; they were then taken ashore by launch. Our captain and VIPs came back onboard the next evening and much activity ensued. Sir Anthony and his secretaries were drafting important letters and signals, which were then taken ashore for onward transmission.

Throughout March there had been 105 air-raid alerts and 402 bombs had been dropped on the island. The pressure was still intense and the German aircraft were as active as ever.

On 3 April an Italian SM79 bomber, escorted by a pair of CR42 fighters, attempted a machine gun attack on HSL107 on patrol near Linosa. The Italians later claimed that they had sunk the boat, but she was in fact undamaged. On the same day a flight of twelve Hurricanes was flown from the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal in Operation Winch. These were newer, Mark IIAs, which it was hoped would be more than a match for the Me109s. They were also piloted by men that had had experience during the battle of Britain. The aircraft were brought in led by Skuas in two flights of six each. The aircraft had been in Gibraltar on 1 April and one of the pilots later described his experiences between 1 and 3 April when they finally landed safely in Malta:

1st April. At Gibraltar. We left the Argus and went about the Ark after lunch. She is the most enormous ship and carries about 160 officers and 1,600 men. Also five squadrons of aircraft. We were supposed to sail at 17.00 hours, but it was postponed. We are not allowed to go ashore, so a party started in the ward room.

2nd April. At sea. Woke up to find everything vibrating like the devil, with the ship doing 24 knots. We have HMS Renown and Sheffield and five destroyers with us. Had a long talk from the Commander (Flying) with all the other pilots on deck procedure for flying off, and then we were shown our proposed course after we take off. In addition to the Skuas who are leading us, we are picking up a Sunderland flying boat after about 100 miles which will lead us the rest of the way. Had a run over my aircraft for R/T test and ran over engine. Everything Ok.

3rd April. The arrival. Was called at 04.00 and got out of bed with a real effort. Had breakfast about half an hour later. All the knives and forks were leaping about the table because we had increased speed to 28 knots. We eventually took off at about 06.20 and everything went according to plan. The only snag was that X made a bad take-off and punctured one of the auxiliary tanks and broke off his tail wheel. He was naturally scared stiff of using up all his remaining petrol and making a bad landing. However, all went well. He landed at the first airfield he saw, which was Takali, where we are now stationed. Most unfortunately Y crashed on landing. He came in too fast and had to swing to avoid something at the end of his run. The undercarriage collapsed. It is really sickening to have an aircraft, which is worth its weight in gold out here, broken through damned bad handling.