The Teutonic Order had been founded as a Crusader order of knights at Acre in 1190 but transferred its seat of war in the name of Holy Christ to the Baltic, fighting Prussian, Latvian, Livonian and Estonian pagans. The pagan Prusy raided across the frontier into the Polish Duchy of Masovia and in order to put a stop to these attacks Duke Conrad invited the Teutonic Order to counter this menace. The knights arrived in 1230 and had crushed the Prusy within a decade of fierce fighting. But once their mission had been accomplished these increasingly unwelcome alien intruders refused to return to Germany. The Teutonic Order continued to expand and by 1283 controlled both western and eastern Pruthenia (Prussia) stretching from the Vistida River in the west to the port of Memel in the east. Later on, by merging with the Order of the Sword, the Teutonic Order gained control over the great trading port of Riga and the lands of Estonia, Livonia, Latvia and Courland. The order now controlled the entire eastern coastline of the Baltic and was a regional great power backed by a superlative army. Military might made the Teutonic Order unpleasant neighbours for Poland and Lithuania and for the Russian principality of Novgorod. Conquest by the Teutons was followed by colonization by German peasants and in 40 short years (1310-50) some 1400 German villages were established in Prussia.

The Teutonic Order’s inexorable Drang nach Osten (March to the East) was greatly facilitated by the state of political chaos and division that reigned in Poland during the 1200s – the country was divided into a series of squabbling duchies and lacked a united front against the German menace to the west and north. In 1320 Poland was united under King Wladislaw I (1260-1333; reigned 1320-33), and then in 1386 Wladislaw Jagiello (c. 1350-1434), the Grand Duke of Lithuania, married Queen Jadwiga of Poland. Two sworn enemies had united against the Teutonic Order, and the Lithuanians, by turning to Catholicism, deprived the order of a propaganda weapon – they were no longer fighting `pagans’. The Poles wanted a corridor to the sea and coveted above all the port city of Danzig but their overriding ambition – in the long term – was no doubt to crush the order once and for all. The order for its part saw its role as continuing the expansion ever southwards and eastwards at the expense of the Poles and Lithuanians. An uneasy period of `peace’ came to an end when the order and Poland-Lithuania clashed over the fate of the province of Samogitia.

Of the two sides, the order was militarily the stronger and more experienced. They had known almost constant success during the previous century and a half against Slav and pagan enemies. The core of their army consisted of the 2-3000-strong Teutonic Knights themselves. They were superbly mounted, armoured, armed and disciplined. In conventional cavalry battles between armoured knights they had few equals. But during the previous decades they had had to supplement their cavalry arm with a numerous German and European mercenary infantry force and specialist troops such as English archers, Genoese crossbowmen and Italian artillery. All in all the order was a formidable war machine compared with its enemies.

The united Royal, or Commonwealth, army under King Jagiello was in fact composed of two entirely different armies that had almost nothing in common in tactics, strategy, combat experience or equipment. The striking arm of the Polish army was its cavalry, which was composed of proud, aggressive and bold armoured knights on some of the finest mounts in Europe. These knights were, man for man, more than a match for their Teutonic enemy. But as for the infantry, it was as poorly equipped and disciplined as the cavalry were not. The Polish infantry was made up of peasant levies with only the most rudimentary weaponry, armour, training and discipline. They were no match for the Teutonic Knights in open battle except in terms of their customary almost suicidal Polish bravery. The Lithuanian army was more Asiatic than European in training, equipment and tactics since it had spent the last centuries fighting and defeating the formidable Mongols across western Russia. As a consequence they relied upon lightly armed and armoured cavalry that was highly mobile and fought the enemy with lightning raids, skirmishes and ambushes. It also contained a large contingent of `Tartar’ (Mongol) cavalry who served as mercenaries and were armed with bows and lassos and mounted on small shaggy steppe ponies. Although these Asian warriors and the Lithuanians were superb light cavalry they were of dubious value in a pitched battle against Teutonic Knights.

In December 1409 Jagiello and his cousin. Grand Duke Witold, Viceroy of Lithuania, met at Brest-Litovsk to discuss the forthcoming campaign. They agreed their armies would combine at Czerwinsk on the Vistula – it was not only equidistant between them but provided a safe and well-protected point to cross the mighty river. Meanwhile Jagiello secured a diplomatic triumph when he got the Landmeister (Master) of the Livonian Knights to agree to a truce. The Lithuanians thus would not face a diversionary attack in the rear from Livonia. The King of Hungary assured Jagiello that his alliance with the order, signed in March 1410, was not worth the paper it was written on: he would not take to the field with a large army. Thus Poland’s rear was also secured.

To keep the order guessing as to what their enemy’s intention was Witold sent Lithuanian forces against Memel while Jagiello’s forces raided the Pomeranian frontier. Jagiello wanted the order to believe that this was where he would attack. But the first ordeal was simply getting his Polish army across the Vistula. A pontoon bridge spanned the 601m (550-yard) wide river at Czerwinsk and it took the Poles three days to get across. By 30 June Jagiello’s Poles and Witold’s Lithuanians had combined. As they set off on 2 July the Bishop of Plock gave the troops a stirring sermon to fight the enemy to the death. His words would no doubt resound on the battlefield.

Meanwhile the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, Ulrich von Jungingen, had failed to concentrate his army, as he was still in the dark about the intentions of his enemy. But he was quite sure the Poles and Lithuanians were easy prey – he could not believe the Poles (whom he looked upon as Slav `barbarians’) were technically advanced enough to construct pontoon bridges. As Jagiello’s army moved north from Gzerwinsk Ulrich was forced to move his army from Pomerania to Kurzetnik on the Drweya River. On 9 July the allied army crossed into Prussia singing Bogurodzica (Mother of God) having covered 90kni (82 miles) in a mere eight days. The following day the Polish-Lithuanian army camped at Lake Ruhkowo, opposite Kurzetnik where the order had erected a strong line of fixed defences. Jagiello was now commander-in¬ chief of the combined Royal army while Pan Zyndram of Maszkowice (a Cracow nobleman) was appointed commander-in¬ chief of the Polish army. Witold remained commander of the Lithuanians.

DISPOSITIONS

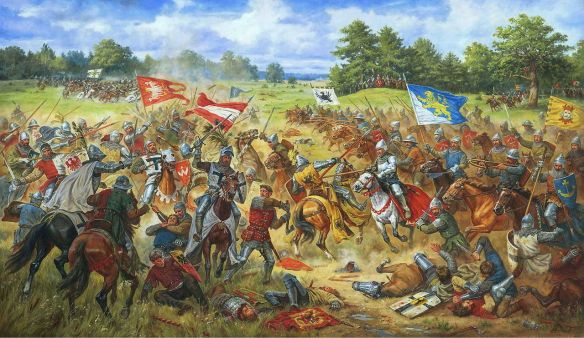

The Grand Master built a series of bridges across the Drwega and his army crossed over to the eastern bank where the battle was to be fought. Here in a rough triangle between the villages of Grünwald, Tannenberg and Ludwigsdorf (Lodwigowo) was the battlefield. It was far from ideal, as the visibility was poor due to the wooded and uneven terrain in this shallow depression that measured 3km (1.9 miles) across. Jagiello’s Polish-Lithuanian army numbered 40,000 cavalry and 10-20,000 infantry. The order’s army, reflecting its origins, numbered a mere 6000 foot soldiers, but was strong in cavalry – some 21,000. The Royal army’s camp was situated near Lake Lubien some 7.2km (4.5 miles) east of Grünwald. Early in the morning of 15 July a Polish knight, by the name of Hanko, rode into camp with news that the enemy was already drawn up for battle. The allies had only begun to get into formation and if Ulrich had attacked immediately he might have won a decisive victory. As it was, the Teutonic army had arrived earlier and dug ditches facing the enemy with two lines ready for battle. Here was open ground with a few woods and isolated copses of trees sloping for 6562m (6000 yards) at a gentle gradient down towards Tannenberg. There was a sharper gradient towards the thicker forests that flanked Lake Lubien. Towards the northern shore of the lake the terrain was highly unsuited to the order’s style of warfare. Lithuanians but the Grand Master wanted them to attack him first. Not wanting to displease Almighty God, whose support was ardently invoked by both sides, Jagiello had spent all morning in fervent prayer in his own private chapel in the camp. He finally bestirred himself and rode out with his bodyguard to the Weissberg – a small hill that gave a good view of the battlefield. If Ulrich thought the enemy would rush into battle in their usual impetuous manner then he was sadly mistaken. Three hours passed with the scorching sun rising ever higher without a single Pole or Lithuanian stirring. Ulrich called one of his aides, telling him if Jagiello could not be enticed into attacking

THE FIRST ATTACK

As stated above, had Ulrich attacked with his ready troops straightaway he might have crushed the disorganized Poles and Lithuanians but the Grand Master wanted them to attack him first. Not wanting to displease Almighty God, whose support was ardently invoked by both sides, Jagiello had spent all morning in fervent prayer in his own private chapel in the camp. He finally bestirred himself and rode out with his bodyguard to the Weissberg – a small hill that gave a good view of the battlefield. If Ulrich thought the enemy would rush into battle in their usual impetuous manner then he was sadly mistaken. Three hours passed with the scorching sun rising ever higher without a single Pole or Lithuanian stirring. Ulrich called one of his aides, telling him if Jagiello could not be enticed into attacking then he would have to be goaded by an appropriately insulting gesture.

The Grand Master sent out his two highest-ranking knights to provoke the `slow-witted’ Jagiello into attacking. One was the Imperial German herald, whose shield displayed the Black Eagle (symbol of the emperor) on a gold background, and the other – with a red griffon on a white background – was Duke Kasimir of Stettin. They rode forth across the fields under a white flag of truce and were politely received by Jagiello – who had hoped the Teutons might be willing to negotiate instead of fighting.

Instead the two knights, rudely and arrogantly, rebuked Jagiello and the Polish-Lithuanian army for `cowardice’. They should come out, said the knights, on the open field and fight like real men. Not surprisingly Jagiello lost his monumental patience, told the Teutonic Knights that they would regret their insolence, told them to return and gave Witold, the actual commander of the army, the signal to commence battle.

The Poles advanced in good order with lances and spears at the ready. On their right the Lithuanians, with their Russian and Tartar auxiliaries, could not be restrained any longer. With an almighty battle cry they crashed into the Teutonic lines, sweeping all before them until the Grand Master committed his knights. These heavily armoured troops fought the Lithuanians to a standstill. The Tartars tried to spring their trap of the controlled retreat to lure the Teutonic Knights into a trap but the plan backfired. Their own troops thought the Tartars were fleeing and began to flee themselves. The knights moved forward methodically, coldly butchering the fleeing Tartars, Lithuanians and Russians. Only three squadrons of Lithuanians and Russians held the line as Witold cut his way through the confusion to beg Jagiello to swing the Poles around and save the right flank from total collapse.

Jagiello could not have made out what was going as the whole battlefield was enveloped in thick dust stirred up by the hooves and feet of thousands of horses and men. A sudden downpour settled the dust and finally the two sides could make out what was going on and who was fighting whom. Witold called up his last remaining reserves to stem the Teutonic attack that had seemed unstoppable only half an hour before. But the enemy had clear visibility. Jagiello was only protected by a small guard and Grand Master Ulrich ordered an attack upon the Weissberg by some of his best knights. One of these, clad in white, rushed forward but was stopped by the king’s secretary. Count Zbigniew of Olesnica, who thrust a broken lance into the German’s side. The white knight fell to the ground where he was bludgeoned and stabbed to death by Polish infantrymen.

THE TIDE TURNS

Meanwhile the fleeing Lithuanians, Tartars and Russians had been prevailed upon to halt and now streamed back as fast as they had fled before. They rode at the enemy with their customary courage and élan. A rain of arrows fell on the Teutonic troops as the Tartars, riding at full gallop, shot a them with their bows, while the Lithuanians and Russians used their swords and battleaxes to good effect.

The Poles had in the meantime held more than half of the order’s army at bay and had forced them back in close combat. As the Lithuanian army streamed back to the fight the Teutonic army began to give way, some even fled while others died where they stood. As the Teutons began to give way they were surrounded on all sides by the enemy. To their credit the Order did not capitulate or flee in wild disorder – most of them, including the Grand Master himself, fought to the death. Others who had been able to disengage from the advancing enemy continued to fight on the road that led to Grünwald. It was in this village that the Teutonic army made its last stand and fought to the death with the Poles and Lithuanians. By 7.00 p. m. the battle was finally won.

The Teutonic Order had ceased to exist as a proper military force. The number of Teutonic dead was 18,000 and 14,000 had been taken prisoner. The Grand Master, his deputies and most of his district commanders {komturs) lay dead on the battlefield. Only two senior knights had survived: Prince Conrad the White of Silesia and Duke Kasimir of Stettin – the same man, presumably, who had taunted Jagiello for his `cowardice’ at the outset of the battle.

AFTERMATH

Instead of marching on the Teutonic Order’s capital of Marienburg to the west the Polish-Lithuanian army – utterly exhausted – remained on the battlefield to divide the loot, rest and recuperate. When it was ready to march on Marienburg – held by Count Heinrich von Plauen and 3000 troops – it was too late. This immense fortress complex with stone walls 8.2m (27ft) high and 2.1m (7ft) thick and ample supplies of food and water proved impregnable. Jagiello’s victorious army arrived on 25 July but failed to make any headway during the two-month-long siege. The war would continue for years and the Order would recover. For the Prussians this defeat left a permanent, humiliating scar that never healed, and in 1914, General Paul von Hindenburg – a Prussian – named his epic World War I victory over the Imperial Russian army in the same region after the village of Tannenberg.