The commander of the Army of the Solemn League and Covenant and the overall leader of the Army of Both Kingdoms was Alexander Leslie. Sixty-two years of age by the time of the Battle of Marston Moor, Leslie was one of the most experienced soldiers in Britain during the time of the Civil Wars.

Even Leslie’s early life was exceptional. Despite an illegitimate birth to `a wench of Rannoch’, he was adopted by Clan Campbell. The Campbells of Argyll were the most powerful family in Scotland, and the fact that they were leading Covenanters later helped to convince Leslie to support the cause.

Like many young Scots of middling wealth and social status, Leslie travelled to the war-wracked Continent as soon as he was old enough, and enlisted as an officer in various Protestant European militaries, first with the Dutch, then the Swedes.

It was in the service of the latter that Leslie made his name. In 1627, he was knighted by the Swedish king, Gustavus Adolphus. In the maelstrom of the Thirty Years War, Leslie and many fellow Scots of the Protestant `Green Brigade’ earned a fearsome reputation. By 1637, Leslie was preparing to retire after almost 32 years of military adventure.

The signing of the National Covenant put paid to that. Leslie liaised with the Swedes to ensure the release of 300 veteran Scottish officers from their army, bringing them back to their homeland to help form the nucleus of the new Covenanter army. The Swedes also supplied arms and ammunition.

Leslie was appointed a Lord General by the Scottish Parliament, and captured Edinburgh Castle from the Royalists without losing a single man. Given command of Scottish forces on the border during both Bishops’ Wars, he duped a larger Royalist army into withdrawing by massing as many lags as he could to make his force seem larger, then boldly inviting the Royalist officers to tour his best troops. Overawed by the bluff, the King’s forces retreated. He went on to win the Battle of Newburn, and captured Newcastle.

In the brief peace of 1641, Charles attempted to woo Leslie by raising him to the Earldom of Leven. The bribe failed, and Leslie took command of the Army of the Solemn League and Covenant. His tactical grit and strategic steadiness went on to bring first York and then Newcastle to the allies, fatally tipping the war in England against Charles. The King himself surrendered to Leslie’s Scottish army in 1646.

Leslie refused to become involved in the chaotic factionalism of the later Civil Wars, and retired from military service. He was arrested twice by Cromwell following Parliament’s conquest of Scotland, and confined to the Tower of London, but the intercession of his old allies the Swedes secured his release.

Leslie was to die on his own estates in Fife in 1661, one of Scotland’s most widely successful military commanders.

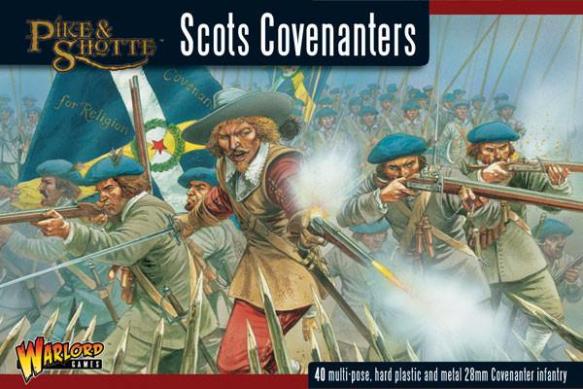

ECW Scots Covenanter Starter Army

RECRUITING AND TRAINING THE COVENANTER ARMY

Right from the start, both Royalists and Parliamentarians were keen to spread the conflict and garner support beyond England’s borders. Parliament was deep in talks with the Covenanters in 1643.

The Scots certainly appeared to be natural allies. There were many English Presbyterian Members of Parliament, and the Puritanism practised by so many Parliamentarian soldiers was not so far removed from the Scottish brand of Calvinism.

The Scots agreed to send an army to assist Parliament in its increasingly protracted and bloody struggle with Charles. In exchange, the English had to help pay for the army, and to promise to introduce Presbyterianism in the Church of England after the war.

Parliament agreed, and a `Solemn League and Covenant’ was signed in late 1643. After less than three years of peace, the Scots were once again marching to war against Charles Stuart.

As early as 28 July 1643, the Covenanters had been recruiting in preparation to assist the Parliamentarians. The Army of the Solemn League and Covenant was comprised primarily of conscripts, called on by the Scots nobility in the age-old feudal fashion.

In every Scottish sheriffdom, a local `Committee of War’ governed the process of deciding who would be chosen from the mandatory regional levy, and how they were to be equipped and paid. Said equipment and uniforms could vary in quality depending on the wealth and dedication of the gentry given the task of leading the individual regiments.

Although traditionally armies of conscripts have been looked down on by professional militaries, the men of the Army of the Solemn League and Covenant were able to match any fighting force in the British Isles at the time.

Many of the rank-and-file had been called on for service in the Bishops’ Wars just three years earlier. Furthermore, hundreds of the officers had experience fighting in continental Europe. Scots had been selling their services as mercenaries to various European nations and factions for over a century.

In particular, since 1618 almost the whole of mainland Europe had been engulfed in the carnage of the Thirty Years War. Many Scots, including the man chosen to lead the army south, the Earl of Leven, had years of hard campaigning experience in the Protestant armies of Gustavus Adolphus.

When the National Covenant was signed in 1638, the Scottish Parliament asked its warring sons to come home and swell its armies in preparation for the conflagration about to engulf Britain. Many did so.

The Scots were also well equipped with artillery. When it marched south, Leven’s army numbered over 21,000 men and was supported by no fewer than eight 24-pdr cannons, one 18-pdr, three 12-pdrs, 57 9-pdrs, eight mortars, and 88 3-pdrs – an artillery train to match that of many 18th-century armies, never mind those of the 17th century.

But while the Covenanters could put a solid force of infantry and artillery into the field, they lacked good-quality cavalry. Scotland is a land of hills and mountains. It has never been horse country. The Scots simply did not have the trained warhorses, nor any real capacity to rear them. Because of this, such Scots troopers as there were had to put up with substandard mounts.

Nonetheless, the use of the lance by half the Scottish cavalry contingent – the other half were equipped with pistols and firelocks – struck fear into their enemies, who had stopped using such weapons decades earlier.