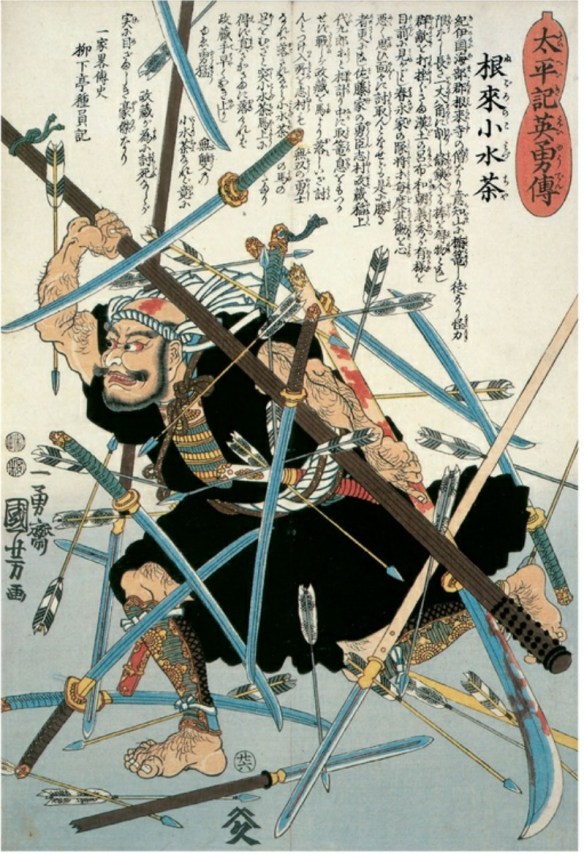

Negoro-no Komizucha. Komizucha was a sohei, a warrior-monk, shown here in battle armed not with the samurai’s weapons, but instead with just a massive club—even so he seems to be holding his own against a fusillade of spears, swords, and arrows.

Sohei warrior monks, Japan c. 900 Some Buddhist monks in Japan chose to follow both a martial and religious lifestyle, with many devoted to the practice of Zen Buddhism. Warrior monks had a role in some of the most turbulent periods in Japanese military history, including the Gempei War in the 12th century. Some Sohei orders grew very powerful, and were able to field armies, especially during the Japanese civil wars of the 16th century.

The monks of the various Japanese Buddhist temple communities, including Nara and Mount Hiei. The term warrior monk comes from the translation of Sohei, so meaning a Buddhist priest or monk and hei meaning soldier or warrior. The monks tended to be belligerent to the point of foolhardiness and the Nara and Miidera monks were heavily suppressed after allying with the “wrong” side during the Gempei War (1180-85).

Monastic forces consisted of a hard core of trained warriors but the bulk of armies were made up of less well-trained and/or motivated members of the temple communities. Their overall effectiveness has probably been overrated under other rules systems. One well known tactic was to place their portable shrine, containing the kami (or spirit) of the temple, in front of the battle line and dare all comers to try and take it!

Armed forces known as sohei (warrior-monks) mounted a potent challenge to aristocrats and warriors throughout the feudal era. The term akuso, meaning evil monks, found in diaries of Heian period courtiers, summarizes the general view of these soldiers that represented powerful temples. While warriors and aristocrats struggled for control of feudal Japan, from the sidelines the sohei fought to unseat both of these forces and instead obtain both land and wealth for the benefit of powerful religious institutions.

The origins of the bands of warrior-monks and the language used to identify these figures can be confusing. For example, the title warrior-monk (the more common English translation of the term sohei) carries varied connotations in different periods, and sohei were not always part of the monastic order at the temples they served. Further, sohei were well armed and skilled in the use of weapons, despite Buddhist precepts prohibiting monks from engaging in such pursuits. In addition, civil codes that limited weapons possession among priests, acolytes, and other clerics had little effect on the many sohei who functioned in institutions not subject to such restrictions. Another common misconception about warrior-monks also relates to terminology. Some scholars have conflated the roles of sohei and yamabushi (mountain ascetics), since both of these religious figures dwelt in mountains and are sometimes identified in medieval sources as similar figures. Despite the apparent similarity to the word bushi, which is also used to designate samurai, the “bushi” in yamabushi is written with a different character than the “bushi” for warrior. The term yamabushi distinguishes ascetics who engaged in mountain pilgrimages and sustained meditation as part of their spiritual practice. However, many powerful temples were located on mountains, and while yamabushi also occupied such territory, they were usually benign figures devoted to solitary religious practice. At the same time, the legions of warrior-monks enlisted by religious institutions were only occasionally referred to as yamabushi in contemporary sources, simply because the temples they served were in mountainous locations.

Temples and other religious institutions were motivated to deploy units of warrior-monks to defend land acquired during the redistributions and lapses in administration practices on provincial estates that occurred in the 10th and 11th centuries. Young warriors employed by private estates as militiamen confused matters by shaving their heads and were often mistaken for sohei in practice and in historical accounts. In some cases, the warrior-monks (including those private soldiers who appeared to be monks, but often were not) became so powerful that they posed a threat to the imperial court and the shogunate. Warrior monks serving Enryakuji, Kofukuji, and Miidera, all temples located near Kyoto or the old capital, Nara, were particularly notorious.

With the burning of Enryakuji by Oda Nobunaga in 1571, the power of the sohei diminished significantly. Efforts mounted by Toyotomi Hideyoshi and the weapons prohibitions instituted in the late Momoyama and early Edo periods finalized the suppression of these warriors.