D. E. Showalter commented that “The image made familiar by Ferdinand Lot and Sir Charles Oman, of medieval warfare as featuring limited discipline, simple tactics, and no strategy at all, has given way to a growing appreciation of the complexity of military operations between the eighth and the sixteenth centuries.” – `Caste, Skill, and Training: The Evolution of Cohesion in European Armies from the Middle Ages to the Sixteenth Century’

G. Phillips, Anglo-Scots Wars, p. 257. However, this relative tactical sophistication did not go unnoticed by contemporaries. The commander of Italian auxiliaries supporting English operations around Boulogne, between 1544 and 1546, ordered the production of diagrams demonstrating how the English were arrayed. On observing how the shot were located behind the defensive line of pikemen, Giovacchino inquired of his English counterpart why he had formed his men in such a fashion. It was explained to him “that the pikemen stoop while the shot fired over their heads.” J. R. Hale, `On a Tudor Parade Ground’, RWS, p. 267. Here then England was clearly engaged in wider European `military conversations’ exchanging ideas with their continental counterparts. By the 1540s the English were not only aware of and employing new `pike and shot’ formations, but were innovating in their own right, with enough success that foreign commanders thought their ideas worthy of diagrammatic notation.

Henry’s England demonstrated an ability to learn from, and retain lessons from one campaign or engineering project to the next. This was facilitated by a civil-military partnership of nobles, garrison-troops, engineers, artisans, administrators and foreign specialists. This was not a standing army or indeed military professionalism as we now know it, but it did demonstrate a degree of `institutional memory’ and a drive for efficiency and modernity. Luke MacMahon recently echoed the findings of this thesis in stating that although it can “hardly be disputed,” that many Tudor soldiers “lacked experience and expertise.(but).there was also present useful numbers of men with considerable military experience and skill, capable of providing a functional command structure.”

The long historiographical tradition that painted a picture of military stagnation in the reign of Henry VIII can now be discarded. Rather the second Tudor was firmly committed to military modernisation, to the integration of hackbutt, longbow, cannon, bill and pike. This was not a radical revolution, old methods were not abandoned, rather they were adapted to operate in cooperation with new military technologies and the new tactical systems being forged in the Italian wars. One can only conjecture as to Henry VIII’s earliest impressions of gunpowder weaponry but the commitment shown to `new technologies’ by his father was surely influential in shaping the younger Tudors’ curiosity “about matters of this kind. “The role of Henry VII in shaping his martial inclination has perhaps been obscured by now increasingly shaky historical assessments of the first Tudor’s pacifism. Recent revisions have instead shown him to be no pacifist. Rather “in war in Brittany, France and Scotland he attempted to live up to the martial reputation of his predecessors and underline his royal authority through success in war.”

This martial vigour was augmented by a commitment to modern military techniques, most evident in the meaningful establishment of an English ordnance and artillery manufacturing industry in the late 1480s. From this perspective considerable continuity is identifiable between Henry VII and Henry VIII and the improvements to the military establishment here described in the period 1509- 1523 can be seen as part of a process of gradual evolution. English troops would not again be engaged on the continent until the 1540s, during which decade they fully mastered and embraced many of the techniques they had been experimenting with throughout the reign.

Gervase Phillips has convincingly identified an “adaptive pattern of military development,” within which “strong connections with the tactical practice of preceding centuries,” were maintained. As Phillips astutely pointed out, the idea of an “early modern military revolution rests on the belief that medieval warfare was a deeply primitive affair… this… is a modernists conceit.” Phillips identified the `grand strategies’ employed in the execution of the Crusades against the Latin East, the responses of military architects of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries to improving siege engines (e. g. the trebuchet) and indeed the large and tactically competent forces that often constituted the medieval army. Phillips’ model repeatedly emphasised continuity between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, “firearms… did not revolutionise warfare but slotted neatly into existing tactical systems.”

One cannot escape the relative merits of what one might term the `evolutionary model’ of military development. Throughout the early modern, and indeed medieval, period, continuity appears to be the dominant theme – as opposed to any sudden revolutionary change – in continental military practice. Such a view, for the period 1494-1559, was recently endorsed by J. Black who concluded that a “consideration of the warfare of the period suggests that `military adaptation’ is a more appropriate term than revolution.” This new approach is most clearly evident in contemporary reflections on the Italian wars. The French descent into Italy, in 1494, had long been held up as marking the differentiation between medieval and early modern warfare, however the relevance of this periodisation has come in for increasing criticism. 91 Thus “rather than arguing that firearms revolutionised warfare, it is important to focus on the way in which they slotted into existing tactical systems.”

At first glance these conclusions find resonance with those of M. Prestwich who noted that “many of the elements considered to typify the early modern military revolution also featured in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century: the increased size of armies, elaborate supply arrangements, complex strategy and effective tactics.” However, Prestwich added the important caveat that:

Although this weakens the case for the early modern military revolution, it does not make an alternative case for gradual steady evolution. Rather, it demonstrates that in different periods, when similar problems presented themselves, closely comparable solutions were developed. Change was not even paced.

R. I. Frost, in his excellent appreciation of The Northern Wars, came to a sympathetic conclusion for the period 1558-1721, wherein “what took place was a series of individual military revolutions, not one Military Revolution.” For Frost, like Prestwich, the “course and timing of change,” was context-specific and “although the process of change was essentially evolutionary, in every case there was a critical point which can be seen as the definitive breakthrough of a new military system.”

The difference between Frost and Phillips is only one of nuance, but this in itself is significant when constructing models of military change. The conclusions of Frosts’ regional study find striking resonance with the pattern of military development and maturation here identified in Tudor England. Employing Frost’s paradigm, the period 1509-23 was essentially a period of evolutionary change, while the 1540s can be seen to have represented, for England, the `critical point’.

Ultimately, it seems unlikely that a satisfactory compromise will ever be reached between the proponents of `revolutionary’ and `evolutionary’ change to the nature of early modern European warfare. Although it is certainly safe to conclude that the `military revolution’ can now no longer be understood in its original context. Roberts’ `definitive model’ appears flawed in the light of recent revisions. To historians and social scientists alike the term `revolution’ has developed a plethora of interpretations, and indeed `definitive definitions’. Nevertheless, to most of us, it still denotes a `violent change’ to the status quo, normally over a relatively short period. Therein lies the problem with attaching the label, `revolution’, to military developments over time. Nevertheless, `revolution’ has become synonymous with the military history of Europe in the early modern period. Roberts’ original model spanned over one hundred years, a period which in itself seems so long as to negate the application of the term `revolution.’ Moreover, recent revisions have extended the `military revolution’ to such an extent, in some cases spanning over three centuries, that there seems very little revolutionary in the model whatsoever. The term is highly subjective; who is to say the development of the trace italienne fortification was any more revolutionary than the crossbow before it, the flintlock or later the bayonet? The application of the term `revolutionary’ immediately gives added significance to the item to which it is attached – often without sufficient corroborative evidence. In the face of these problems what are we left with? Is the military revolution debate thus left bankrupt? Is it simply an academics’ paper chase? This, it seems, would be to go too far. The military revolution debate, like any other form of historical classification has provided a necessary and thought-provoking framework. However the profusion of alternative interpretations has ensured the concept now bears little resemblance to any reasonable definition of a revolution. It seems fair to conclude that the original notion of an early modern European `military revolution’ is now defunct.

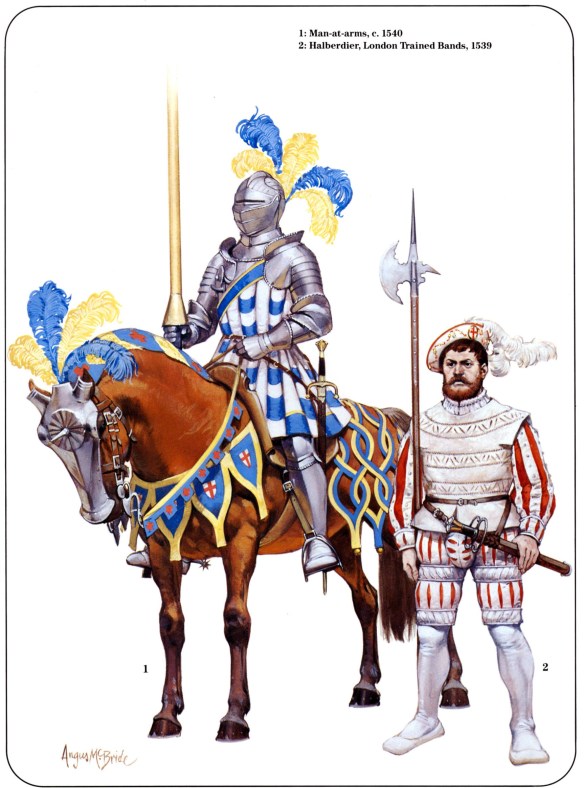

Pike and Shot Campaigns