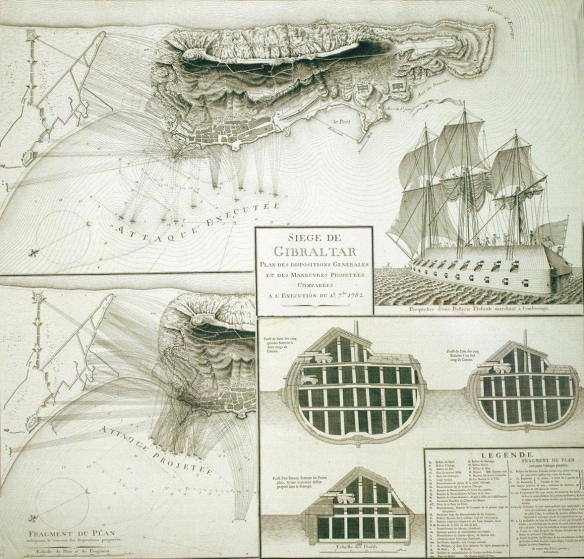

A projected assault upon Gibraltar.

The build-up of forces ranged against Gibraltar was increasing daily, and just as the tunnelling started, one soldier noted: ‘above ninety sail of Spanish transports arrived this evening, with a bomb-ketch, from the east, with troops and stores for the camp’. A few days later, he observed: ‘the number of vessels that have arrived at Algesiras exceeds a hundred: about ten battalions of troops have been landed from them’. Horsbrugh was more precise: ‘the enemy are pitching tents for a regiment in white to the right of the Catalan Camp on the south west face of the Queen of Spains Chair, and for the regiment in blue uniform on the west of Bona Vista Barracks’. This was a massive reinforcement of French forces who were no longer needed on Minorca.

The floating batteries were being monitored from Gibraltar, with increasing concern as more and more of the old merchant ships were converted. Although the garrison now had gunboats – some completed, others nearly so – to cope with the menace of the Spanish gunboats, it was difficult to see how they could withstand an attack by floating batteries. Spain was pouring everything into the scheme, and in Boyd’s journal it was acknowledged that Gibraltar’s inhabitants were in a state of terror: ‘The Enemy have now, about two hundred sail of vessels between Algaziers and the Orange Grove … This show of shipping before us puts our inhabitants and women in a great panic. They are hourly gathering up the little remains that devastation has left them, and carries it to caves, creeks and corners in the Rock, in order to save what they can of their remaining substances, as we daily expect a very heavy attack and storm both by sea and land.’ The inhabitants were still in makeshift huts and tents in the south, as were many of the soldiers, and after coming off guard duty, William Maddin from the 12th Regiment raised his musket, ‘making believe to shoot a girl in camp’. He had forgotten to unload his weapon and shot nine-year-old Maria Palerano, an inhabitant, through the head. She died instantly. Towards the end of May, Maddin was put on trial for murder and acquitted.

In spite of the anxiety of waiting for the attack, unexpectedly good health was recorded within the garrison at the start of June: ‘The Doctors reports does not show one man in the scurvy, and the fever brought here by the 97th Regiment is almost spent (as the men recovers very fast), neither has it been very fatal, so that we are at present, in general, in a much better state of health through the Garrison than we’ve been in since the Siege begun.’ It probably helped that supplies were managing to reach the garrison from Leghorn, Algiers and Portugal, and one Portuguese boat recently obtained thirty thousand oranges and a few casks of oil at Tetuan by the captain claiming the cargo was for Cadiz, then bringing it undetected to Gibraltar. Although the most effective remedy for scurvy was known to be fruit and vegetables, other ideas were still being pursued, and the Garrison Orders in early June said: ‘One quarter and half of a pint of vinegar to be issued to every ration, till further orders. The surgeons of the different corps are of opinion that this will be a great preventative in the sad effects of the scurvy.’

One asset to the garrison was the completion of the gunboats, with the final one being launched on 4 June, the king’s birthday. There were twelve in all, bearing suitable names such as Dreadnought and Vengeance. The day was celebrated with a royal salute of forty-four guns, the age of the king, all directed towards the Spanish siegeworks, while the ‘Governor honoured himself this morning with a captain’s guard and a standard of colours of the 73rd Regiment of Highlanders dressed in their tartan plaids’. There was also another glimmer of hope – that red-hot shot or heated cannonballs might deal with the floating batteries. Although known for decades as a theoretical technique, this dangerous procedure had until now been rarely used. It also required a great deal of fuel, which was in short supply. Solid cast-iron cannonballs were heated in a furnace and were fired by placing a cartridge into the gun, ramming down a well-soaked wad, followed by a heated cannonball. Another wet wad was rammed in on top of the red-hot shot if the cannon was to be fired while pointed downwards. Experiments at the beginning of the siege had established that a cannonball took about twenty-five minutes to heat and was still hot enough to ignite gunpowder after fifty minutes. On hitting the target, the intense heat made red-hot shot extremely difficult to deal with, and it set fire to anything combustible.

The technique of using red-hot shot was difficult to master. Early on, some equipment for heating shot had been set up, with Captain Paterson noting that ‘a detachment of artillery ordered to practise the motions of firing red hot shot daily’. These ‘motions’ were probably done with cold shot, but now that an attack was imminent, the gunners needed to be able to use the real thing. The red-hot shot furnaces, sometimes called grates or forges, comprised a strong iron framework to support a grid or rack to hold the cannonballs, with a fire of wood, coal and coke underneath. The heated shot was manhandled with specially made tools such as tongs and two-handled shot carriers, which were all made on Gibraltar by blacksmiths from the artificers.

The loaded cannons had to be aimed and fired quickly before the shot burned through the wad and fired the gun prematurely, which is what occurred at a practice session in early June: ‘On the 7th, our artillery practised from the King’s Bastion with red-hot shot against the Irishman’s brig.’ A few weeks earlier, this brig had sailed towards the Old Mole, but ran aground when fired on by the Spaniards. After being rescued, the captain was severely rebuked, but he explained that before leaving Cork in Ireland he had heard about the successful sortie and was told that the Old Mole, his old anchoring place in peacetime, was open. The garrison gunners were now using his vessel for red-hot shot practice: ‘In the first round, one of the artillery-men putting in the shot, the fire by some means immediately communicated to the cartridge, and the unfortunate man was blown from the embrasure in some hundred pieces. Two others were also slightly wounded with the unexpected recoil of the carriage.’

By now, the tunnel being cut by Ince was progressing steadily, but on the same day as this accident, Horsbrugh said that two miners were injured: ‘two men of the 72nd Regiment had the misfortune to lose each a leg by the blowing up of a mine in the communication we are making through the Rock to get at the Notch on the North Front, and one of them died soon after being carried to the Hospital.’ Because they were mercifully rare, such accidents were more newsworthy than the commonplace casualties caused by the Spanish bombardment, but an incident a few days later, on 11 June, turned out to be the worst single day for casualties in the last three years. Garrison working parties were making considerable improvements and repairs to the defences while the Spaniards were focused on the floating batteries and their guns remained fairly quiet, but during a random episode of firing, a single shot caused havoc. An emotional description was set down in Boyd’s journal:

Between 10 and 11 o’clock this forenoon a large shell from the enemy fell in the door of one of the small magazines at Willis’s, on Princess Ann’s Battery (where a great working party were repairing the fortification there); the shell on its explosion blew up the magazine which contained about 96 barrels, or, 9,600 pounds of powder, killing 13 men and wounding 12 more. This has been the most fatal day since the beginning of the siege. How horrid and dreadful to behold the terrible blast and explosion! To feel the town and the Rock tremble, and to see men, stones, timber, casks, mortar and earth flying promiscuously in the dark smoky cloud far above the surface, in the air; and on their coming down are dashed to pieces on the craggy rocks, some thrown headlong down the dreadful precipice into the Lines, a most shocking exit! having not time to offer up to God a single prayer preparatory to their acceptance in an everlasting state.

The huge explosion was clearly visible to those at the Spanish Lines, who were heard cheering at the sight of the disaster. Their firing continued to concentrate on the same spot, in the hopes of another spectacular hit: ‘The enemy poured in shot and shells upon that part as thick as hail, so that it was night before all the killed and wounded were gathered up.’ Because a mixture of soldiers had been drafted into the working party doing the repairs, the final casualty list was thirteen rank-and-file soldiers and one drummer killed, with many more injured.

Over at Algeciras, tents were now visible for the workmen who were converting the old warships into floating batteries. Even with powerful telescopes, though, observations from the Rock could yield only a limited amount of information about what the Spaniards and French were preparing, and all kinds of rumours circulated. Definite information at last arrived on 21 June from two former Genoese inhabitants, who had been captured when bringing a cargo to Gibraltar from Algiers. They had been taken to Algeciras, from where they had just managed to escape in the prison-ship’s boat. From them, it was learned that French reinforcements had indeed arrived, that ten ships were being converted into floating batteries, though a shortage of carpenters was causing delays, and that the Spaniards were in high spirits.

On the same day, the French troops finished landing, and it was said that there were now thirty thousand men in the camp. The commander of the Minorca siege, the Duc de Crillon, had also arrived to take over command of the siege of Gibraltar, and the two Genoese, Drinkwater said, ‘informed us that the grand attack was fixed to be in September, but that all, both sailors and soldiers, were much averse to the enterprise’. If they were correct, then the garrison still had at least two more months to prepare.