After the defeat of Crassus, the Romans expected a Parthian invasion to overrun and claim the poorly defended territories of the eastern Mediterranean. Instead, the Parthians launched plundering raids into Syria and Asia Minor that undermined, rather than vanquished, Roman authority in these regions (53–52 BC). The death of Crassus destabilised Roman politics and in 49 BC Julius Caesar was drawn into a civil war with a political faction led by his former friend and colleague, Pompey. When Caesar emerged victorious and was declared Dictator, he prepared the Roman legions for a further campaign against Parthia. His plan was to avenge Crassus by conquering the Parthian Empire and extending Roman rule as far as the Oxus River. But Caesar’s autocratic rule had alarmed traditionalists in Rome who conspired to have him assassinated before he could begin his war against the Parthians (44 BC).

The death of Caesar caused another civil war as Mark Anthony joined with Caesar’s nephew and adopted son Octavian to establish their own joint rule over the Roman Republic. They achieved a decisive victory over the pro-republican faction at the Battle of Philippi in Macedonia in 42 BC. Octavian then assumed power in Rome and Antony took authority over the Roman commands in the Eastern Mediterranean. The responsibility therefore fell on Antony to enact Caesar’s plans and conquer the Parthian Empire.

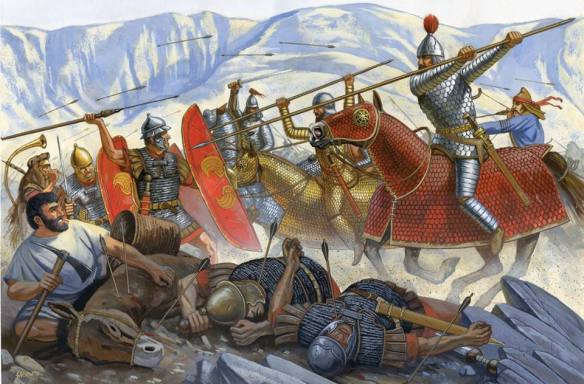

Fresh from his dalliance with Cleopatra, Antony set out to conquer the Parthian empire, following a battle plan he discussed years before with Caesar. Avoiding Crassus’ mistake of striking directly through Mesopotamia, Antony took his massive army north through Armenia. Always impetuous, Anthony refused to wait for his baggage wagons and siege equipment and marched with his main army to Phraaspa, the Royal City of Media, leaving Oppius Statianus in charge of the siege train with a fairly large security force. When king Phraates heard about Antony’s folly, he led a strong force of cavalry to attack the wagon train. Phraates’ cavalry quickly surrounded the wagons, killed the guards, and destroyed all the equipment. Antony could not capture Phraaspa without his siege equipment. Despite winning a few minor skirmishes, Anthony was forced to withdraw from Media in the winter, suffering extremely heavy losses to both Parthian attacks and the harsh weather.

After his victory at Philippi, Mark Antony was intent on waging war against the Parthians and avenging the defeat at Carrhae. Anthony sent Pubulius Ventidius Baussus ahead to pave the way. Ventidius was one of the most successful Roman generals who fought the Parthians. His use of ranged weapon troops and terrain to combat the Parthian cavalry gave him several victories.

Ventidius marched into Syria and encountered Quintus Labienus, a renegade Republican officer who had served under Brutus and then joined the Parthians. Ventidius gave chase, tracking Labienus down at the Cilician Gates, the main pass through the Taurus Mountains that separated Cilicia from Anatolia. Ventidius made camp on the heights while Labienus, expecting Parthian reinforcements, camped a short distance from the away. The Parthian cavalry under Pacorus soon arrived. Utterly fearless of the Romans, the Parthian horsemen did not wait to join Labienus but instead directly charged the heights. The Roman force, well supplied with missile troops and benefitted from the terrain, repulsed the attack and drove off the Parthians. The surviving Parthians fled to the Labienus’ camp. Labienus avoided the fight and managed to escape again after dark. The way was now clear for Antony to invade Mesopotamia.

Antony invades the Parthian Empire

Antony utilized the Egyptian city of Alexandria as his new political headquarters and with the support of Roman client kingdoms in the Near East he prepared for a new war against the Parthians. He mobilized an army of 100,000 soldiers including up to 60,000 legionaries from sixteen legions and 10,000 cavalry. The allied forces included 20,000 Hellenic troops provided by Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt and several other kingdoms in the Near East subject to Rome. The King of Armenia also offered 6,000 cavalry and 7,000 infantry to support the Roman conquest. A convoy of 300 wagons was organized to transport essential siege machinery including an 80-foot long battering ram. The wagons also carried crucial food stocks for the campaigning army. Antony believed that this force was sufficient to defeat a Parthian army that could probably mobilize about 40,000 mounted troops including 4,000 armoured lancers commanded by their new king Phraates IV.

In 36 BC the Roman army crossed the Upper Euphrates and invaded the large kingdom of Media Atropatene which dominated the northwest quarter of the Parthian Empire. Their first target was the Median winter capital Phraaspa (Maragheh) which was almost 300 miles, or three week’s march, from the Euphrates frontier. The Roman soldiers were equipped with slings that had proved effective in countering volleys of enemy arrows. Dio reports that ‘the numerous slingers routed the enemy because they could shoot farther than the Parthian archers.’ A hail of lead sling-stones could inflict ‘severe injury on all Parthians including men in armour’, but this weapon rarely killed and the enemy could quickly retreat if overwhelmed or injured.

Antony achieved a rapid advance by marching ahead of the slow-moving train of accompanying wagons which were guarded by at least two Roman legions and a large force of allied Hellenic troops. But the Parthian army ambushed the convoy, massacred its guard of 10,000 legionaries, plundered the Roman supplies and burnt the siege equipment. Plutarch explains that this was a decisive point in the war and ‘the king of Armenia, despairing of the Roman cause, withdrew his forces and abandoned Antony.’

Antony reached Phraaspa with a force of more than 50,000 legionaries, but the fortified city was well-garrisoned and provisioned to withstand long-term siege. The Roman siege machinery that had been destroyed could not be replaced using local timber or the palisade wood that the legionaries carried to fortify their camps. The Romans therefore began to build a large earthen mound next to the city wall to surmount the defences and provide a platform for attack. This was a time-consuming, labour-intensive effort and as their supplies dwindled large parts of the army were left immobile. The Parthian army appeared outside the legionary camps arrayed in full battle formation to yell repeated challenges and insults which badly affected Roman morale. Antony was concerned that this ‘dismay and dejection would increase through inactivity,’ so he assembled ten legions and with the support of his cavalry he marched into the countryside to seize all available food supplies. This he hoped would draw the Parthians into a decisive battle.

Leaving a retaining force near the city walls, Antony marched his army a day’s journey from Phraaspa. The following day, the Parthian army including up to 40,000 mounted warriors appeared within sight of the Roman legions. They waited for the Romans to renew their march then gathered a crescent-shaped formation to attack the legionary columns from their flanks. But at a given signal the marching legionaries began a complex manoeuvre to bring columns of men into rank formation and face the Parthian army in a combat-ready battle-line. Plutarch describes how the Parthians ‘were awed by Roman discipline and watched the men maintain equal distance from one another as the marching lines rearranged in silence without confusion. Then soldiers brandished their javelins.’ Antony had issued orders that the Roman cavalry were to ride against the Parthians if they came within range of a legionary charge.

The Parthians interpreted these silent manoeuvres as the early stages of a Roman withdrawal and were not alarmed when the space between two armies narrowed. But at a given signal, ‘the Roman horsemen wheeled about and rode against the enemy with loud shouts.’ The shocked Parthians did not have time to unleash a full volley of arrows as 10,000 Roman cavalry charged into their midst. The larger Parthian force was able to withstand and repel the Roman charge, but the delay gave the legionaries time to dash forward and reach their enemy. Plutarch describes how battle was joined with shouts and the clash of weapons, but ‘the Parthian horses took fright and broke contact, and the Parthians fled before they were forced to fight the legionaries at close quarters.’ The legionaries pursued the Parthians for up to 6 miles, then the Roman cavalry continued the chase for 18 miles, but the enemy did not regroup for battle.

This engagement was considered a Roman victory, but when the legionaries took a tally of the battle they counted only eighty Parthian casualties and thirty prisoners. Plutarch explains that ‘Antony had great hopes that he might finish the whole war or decide a large part of the conflict in that one battle.’ But the tactics and casualty figures suggested otherwise, especially as the Roman army had already lost 10,000 legionaries in the earlier ambush. Plutarch reports that ‘all were affected with a mood of despondency and despair. They considered how terrible it was to be victorious, yet have killed so few of the enemy, when they had been deprived of so many men when they themselves had suffered defeat.’

The following day the Roman legions began the march back to Phraaspa. But the Parthian army had rallied and reappeared, ‘unconquered and renewed, to challenge and attack the Romans from every side’. Plutarch explains that the Romans only reached the safety of their siege camp after ‘much difficulty and effort’. When they saw the condition of the returning Roman army, the defenders of Phraaspa launched a successful sortie to destroy the improvised siege-works and put the guards to flight. To maintain discipline Antony ordered an immediate ‘decimation’ where one in ten of the soldiers in the disgraced units were selected for summary execution by their colleagues.

By this stage famine was imminent as Roman supplies were depleted and any troops sent on foraging parities suffered heavy casualties. Furthermore, winter was approaching and both armies knew that severe cold and frosts would soon cover this exposed landscape. Antony had no choice but to abandon the siege and withdraw to Roman territory. Plutarch reports that ‘although Antony was a natural speaker and could command armies with his eloquence, he was overcome with shame and dejection and did not make his usual speech to encourage his troops.’ The Roman retreat was announced by a sub-commander who perhaps reminded the legions that Armenia was now considered to be hostile territory, since its king had changed his allegiance.

Antony chose an alternative route back to Roman territory that crossed hills rather than the open treeless stretches of plain which would have been favourable to pursuing Parthian cavalry. The hill route passed through well-provisioned villages, but the Parthians were prepared and ‘seized passes before the Romans approached, blocked routes with trenches or palisades, secured water-sources and destroyed pasturage’. On the third day of the march the Parthians breached a dyke and flooded the ground in preparation for an ambush. But the legions were quick to form defensive formations with slingers and javelin-throwers launching missiles. The forward march continued and Antony ordered his troops not to leave the marching column to pursue the enemy. On the fifth day a detachment of light-armed troops guarding the rear disobeyed his orders and followed a Parthian attack force away from the main column. The detachment was immediately surrounded by Parthian reinforcements and Antony fought a fierce battle to retrieve his troops. Almost 3,000 Romans were killed and a further 5,000 soldiers suffered serious wounds in this single engagement.

The following day the Parthians again rode against the Roman rear-guard and encountered several units formed up behind a wall of shields (the testudo). They assumed that these immobile ranks were units that had abandoned the march prior to surrender. The Parthians therefore dismounted and approached on foot. But the legionaries counter-charged and cut down the first ranks of the enemy with their short-swords.

As the march continued the weather worsened with severe frosts and driving sleet further hampering the Roman retreat. Many wounded Romans had to be carried or supported, and the accompanying pack animals began to die from exhaustion and exposure. Provisions were almost exhausted and the troops became ill from eating harmful wild plants. But the Parthians still followed the retreating Romans, guarding any nearby villages that the legionaries might try to seize for shelter or supplies.

Antony considered leaving the hills, but he received a Parthian deserter who warned that the Roman column would be annihilated if it ventured onto the open plains. One source suggests that this man was a survivor from the campaign by Crassus who had undertaken to serve his Parthian captors, but could not bear to see his countrymen massacred. Florus reports, ‘The gods in their pity intervened, as a survivor from the disaster of Crassus dressed in Parthian costume rode up to the camp. He uttered a Latin salutation, inspired trust by speaking their language and told them of imminent danger’. Florus asserts that ‘no disaster had ever occurred comparable with the one which now threatened the Romans.’

The Parthian deserter warned Antony that the hill route was taking them across a district where there was no fresh drinking water. Antony therefore instructed his soldiers to fill all available leather-skin containers and carry additional water in their upturned helmets. The Romans began the 30-mile march across this district at night with the mounted Parthians still in pursuit. By morning the Romans had reached a clear, cold-running stream that was heavily saline. Despite direct orders from Antony, many thirsty soldiers drank this harmful water and were debilitated by a sudden sickness. After miles of further forced march, the exhausted legionaries finally reached shade and clean drinking water, but they were only permitted a short rest. Their guide promised Antony that they were close to a boundary river and rough terrain that the mounted Parthians would not cross in pursuit.

The night before they reached the river there was a large-scale disturbance in the Roman camp. A group of deserters killed comrades who had been guarding the pay and precious metal artefacts carried by the legions. The Parthians saw the disorder and attacked. Antony feared that a breakdown in the Roman formations would cause a mass rout, so he ordered a member of his personal guard to kill him if his capture seemed imminent. The freedman was instructed to cut the head from Antony’s corpse so that it could not be taken and displayed as a Parthian trophy. But Roman training and discipline held enough of the ranks together to repel the enemy throughout the night. In testudo formation the Roman column finally reached the banks of the boundary river the following day. The cavalry formed a guard as the sick and wounded were brought across the river to safety in the territory that lay beyond.

It had been twenty-seven days since Antony had abandoned the siege at Phraaspa and begun the retreat back through the hill country. Since then, his army had fought at least eighteen defensive engagements and suffered heavy casualties due to enemy action, exposure, sickness and fatigue. According to Plutarch the Romans lost 20,000 legionaries and 4,000 cavalry on the return march alone. To these figures can be added the two legions (10,000 troops) destroyed with the siege equipment on the outbound expedition. Florus claims that barely a third of the expedition force (23,000 troops) reached safety, meaning that 12,000 were captured or killed at Phraaspa. Roman casualties were over 40,000 men, the size of the entire army led by Crassus. Antony had probably lost two-thirds of the soldiers taken on campaign. This reduction in Antony’s forces proved significant when Octavian successfully challenged and defeated Antony to gain control over the entire Roman Empire (32–30 BC).

Augustus and Parthia

In 27 BC Augustus (Octavian) formally accepted the position of Emperor and became the uncontested ruler of the entire Roman Empire. But important political legacies of the civil war period were still unsettled. Julius Caesar had planned the conquest of Parthia in revenge for the Roman defeat at Carrhae and Antony had suffered humiliating setbacks in his failed campaigns against the Parthian Empire. Augustus was expected to rectify this situation and restore Roman honour in the Middle East.

But eastern conquests were not an easy prospect for the Augustan regime. Two Roman armies had been almost annihilated attempting first the Euphrates invasion route and secondly the Median route into Parthia. Furthermore, any invasion of Parthian territory would take large numbers of Roman troops far from the centre of their Mediterranean Empire at a time when Augustus needed to be near Rome to oversee political affairs and guarantee the dictatorial reforms that he had introduced. Any Parthian campaign needed to be undertaken by generals that Augustus could trust to pursue conflicts in distant regions far from his direct supervision. Alexander had been able to conquer the core territories of the Persian Empire in just three years (331–328 BC), so perhaps the Romans could expect similar progress if everything in their high-risk invasion plans were to succeed. Appian records that even Caesar’s invasion plans had set out a three-year schedule for the conquest of the Parthian Empire.

The Latin poet Horace reveals the prevalent Roman attitude during this period (30–20 BC). In one instance he refers to ‘the Parthians, threatening Rome’ and in another context suggests that the Roman army needed to develop a cavalry corps equipped with long lances to counter the tactics of mounted Parthian forces. He asserted that ‘our youth should learn how to use the steed and lance to impose fear on the Parthians.’ This is probably based on popular debate as to how to prepare the legions for the prospect of eastern wars.

Other comments by Horace promote Roman supremacy, for example, ‘The Roman soldier fears the deceptive retreat of the Parthians, but Parthia dreads Roman dominance.’ Elsewhere he comments, ‘who fears Parthian or Scythian hordes, or dense German forests, while the Emperor lives?’ The view that the Romans might be about to attack Parthian territory is also conveyed by his statement that ‘Rome, in warlike pride will stretch a conqueror’s hand over Media.’