Unlike earlier nineteenth-century conflicts, the Sino-French War was the first war during which China possessed a modern navy. Credit for this development largely goes to Li Hongzhang who, during 1870 to 1895, was governor-general of the northern province of Zhili, and a primary sponsor of China’s modernization. Not only was Li still considered to be the head of the Huai (Anhui) Army, which had born the brunt of fighting against the Taiping, the Nian, and the Muslim Rebellions, but he soon became responsible for forming the Beiyang Navy in China’s northern waters. The Chinese government ordered the development of three other modern fleets as well, based at Guangzhou, the Fuzhou Naval Yard in southeast China, and along the Yangzi River.

China’s need for a modern navy was first revealed during the Opium War, but was dramatized in 1873 when Japan claimed the Ryukyu (Okinawan) Islands as Japanese territory. These islands had become a Chinese tributary in 1372, but from 1609 were slowly dominated by the Satsuma feudal state in Japan. The incident that sparked Japan’s action was the 1871 massacre of fifty-four shipwrecked Ryukyu sailors by Taiwanese aborigines. When Beijing refused to take action in what was technically a part of China, the Japanese launched their own expedition in 1874 and sent troops to Taiwan. Lacking an effective navy to counter the Japanese force, China was forced to pay Japan an indemnity both for its expedition and to compensate the murdered sailors’ families. Beijing also agreed not to dispute Tokyo’s claim to the Ryukyu Islands. In 1879, Japan formally annexed these islands and changed their name to the Okinawa Prefecture.

Beijing could not counter foreign aggression from the sea without a modern navy. Previously, funds for building a navy were particularly scarce because of the military demands of opposing the Muslim rebellion in Xinjiang and resolving the Ili Crisis. In addition, the Manchu Court decided in 1874 to use scarce funds to rebuild the Summer Palace; although widely condemned by westernizers as a waste of money, the construction of a new Summer Palace was intended to prove to the Han Chinese that the Manchus were still firmly in control, and so had important domestic consequences.

Li Hongzhang was the leader of a group of Qing officials who pushed for building a proposed forty-eight-ship navy. He argued persuasively that Beijing was vulnerable mainly from the coast, not from the western borderlands. Still, although Li obtained permission to purchase ships from abroad beginning in 1875, only two million taels were set aside for this task. This amounted to just a fraction of the sum Zuo Zongtang received during the same years to fund his Xinjiang expedition.

As John Rawlinson recounts in great detail in his study of Chinese naval development, Li had a particularly difficult time deciding whether China should build ships herself or should buy them from British, French, and German shipbuilders. As a result of his indecision, by the early 1880s the various Chinese fleets were far from being standardized and so experienced great difficulty working together as units. Accordingly:

In that disordered buy-and-build situation, there was no plan, no grasp of the problem. There were only varying degrees of hostility to China’s several external foes. Much money was spent, but with little effect. The variety of equipment, which reflected the political compartmentalization of the coast, contributed to the lack of coordinated action and grand strategy. Li Hongzhang only added confusion with his wily and opportunistic purchasing of ships and arms.

By 1882, the Qing Navy consisted of approximately fifty steamships. While China built half of these at either the Shanghai or Fuzhou shipyards, the government purchased the other half abroad. For example, China ordered four gunboats and two 1,350-ton cruisers from England, while ordering two other Stettin-type warships and a steel cruiser from Germany (the German vessels, however, did not arrive in China until after the Sino-French War was over).

Not surprisingly, considering Li Hongzhang’s political power, many of the best and most modern ships found their way into Li’s northern fleet, which never saw any action in the Sino-French conflict. In fact, fear that he might lose control over his fleet led Li to refuse to even consider sending his ships southward to aid the Fuzhou fleet against the French. Although Li later claimed that moving his fleet southward would have left northern China undefended, his decision has been criticized as a sign of China’s factionalized government as well as its provincial north-south mindset.

While China possessed much of the equipment for a modern navy by the early 1880s, it still did not have a sufficiently large pool of qualified sailors. One of the major training grounds during the early 1870s was at the Fuzhou shipyards, which had hired foreign experts to conduct training classes. By the late 1870s, many of the foreigners had left Fuzhou, and a new naval academy was opened at Tianjin, in northern China. This academy lured many of the best-trained Chinese sailors away from southern China.

By 1883, therefore, at the outset of the Sino-French War, China’s navy was poorly trained, especially in southern China. Although many of China’s modern ships were state of the art, the personnel manning them were relatively unskilled: according to Rawlinson, only eight of the fourteen ship captains that saw action in the war had received any modern training at all. In addition, there was little, if any, coordination between the fleets in north and south China. The lack of a centralized admiralty commanding the entire navy meant that at any one time France opposed only a fraction of China’s total fleet. This virtually assured French naval dominance in the upcoming conflict.

The Mawei Battle [Battle of Fuzhou]

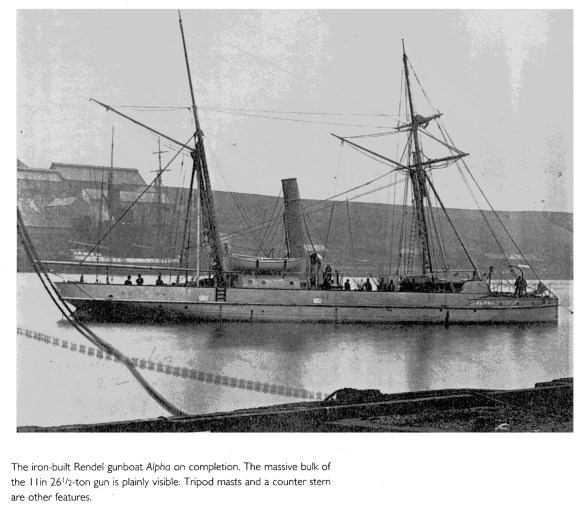

The Chinese flagship Yangwu and the gunboat Fuxing at anchor off the Foochow Navy Yard on the eve of the battle.

The Chinese flagship Yangwu and the corvette Fuxing under attack by French torpedo boats No. 46 and No. 45. Combat naval de Fou-Tchéou (‘The naval battle at Foochow’), by Charles Kuwasseg, 1885.

Spurred on by their defeat at Baclé, the French decided to blockade the Chinese island of Taiwan (Formosa). Beginning on 5 August 1884, Admiral Lespes bombarded Taiwan’s forts at Jilong (Keelung) Harbor on the northeast coast and destroyed the gun emplacements. However, Liu Mingchuan, a former commander of the Huai Army, successfully defended Jilong against an assault by Admiral Lespes’ troops the following day; the French abandoned this attack in the face of the much larger Chinese forces. While the Chinese Army enjoyed limited victories in Annam and on Taiwan, the Chinese Navy was not so successful. On 23 August 1884, a French fleet of eight ships under Admiral Courbet challenged and destroyed all but two of the eleven modern Chinese-built ships at port in Fuzhou Harbor. The heart of the French force was the 4,727-ton Triomphante, which led the artillery attack. Within the space of only one hour, naval bombardments destroyed not only the cream of China’s southern fleet but also the Fuzhou shipyards, which had been built with French aid beginning in 1866. This attack left approximately 3,000 Chinese dead, and damages have been estimated as high as fifteen million dollars. Rawlinson has discussed this naval battle at some length, and has concluded that the “French advantage was not overwhelming” and that: “Had they been decisive, the Chinese might have seized a last opportunity.” The French took advantage of the swift tides in Mawei Harbor to move against the Chinese ships, which were still moored in their docks. Beginning with the deployment of their torpedo boats, the French then used their heavy 10-inch guns to destroy first the Chinese fleet, and then the neighboring dockyards.