Turn on CC for English subtitles.

The Hussite militiaman holds a distant forerunner of the modern rifle – a basic hand-held gun containing a simple explosive charge. Firearms were an important part of Hussite tactics, as a soldier could be trained to use a firearm, in a matter of weeks. Since a firearm required little training to operate, the order maintained by mounted knights in Europe could be undermined by a peasant with a gun. Wagons provided the Hussite infantry with mobile, ready-made fortifications. Initially drawn by four and later up to eight horses, the wagons were manned by troops armed with a mix of missile weapons (crossbows but increasingly handguns) and flails or billhooks. The former compelled the enemy to attack, the later defeated him when he did so.

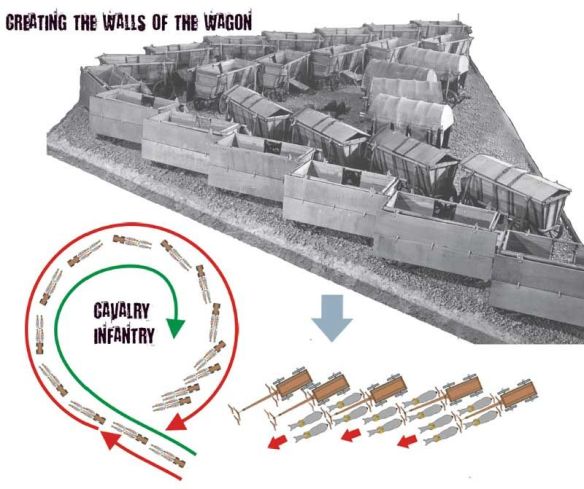

Every problem has its solution: how could peasants armed with agricultural implements hope to contend with well-armoured and supremely confident knights wielding modern weapons? Whether it was lateral thinking, divine inspiration or previous experience, Jan Ziska found the answer in the use of wagons.

God loomed large in the mind of medieval man, who was surrounded by phenomena like birth, plague and the Mongol invasions for which he had no other explanation than `God wills it’. But he could see the enormous gulf between what was said by the clergy, `poverty and chastity’, and what they did, `profligacy and licentiousness’. Consequently, in several places in Europe a counter-movement sprang up. In Bohemia Jan Hus, a rector at Prague University, preached against the behaviour of the clergy. His words were warmly received by his congregation, but not by the church, which began to feel threatened. Under a guarantee of safe conduct from the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, also King of Hungary, and at the request of the pope he travelled to Rome in 1415 to address the Council of Constance. Here he was imprisoned, tried and burnt as a heretic.

THE HUSSITE MOVEMENT

Outraged by this duplicity, numerous small groups of dissidents joined under the name of their martyr and the Hussite movement was formed. In 1417 the church declared all of Jan Hus’s followers to be heretics and sent in an army raised by the Holy Roman Emperor. The situation went from arrests, trials and burnings to open rebellion following an incident in 1419 when some of the king’s councillors were thrown from an upper window in Prague to their deaths amongst the crowd below. This incident is now known to history as the first defenestration of Prague.

On 1 March 1420 the pope declared a Crusade against the heretics. Newly crowned Sigismund of Hungary raised an army in neighbouring Saxony and invaded. The Hussites elected four military commanders, one of whom was a half-blind but sharp-minded former royal gamekeeper called Jan Zizka. He had already been successful in December the previous year when he mounted small cannons on seven wagons to repel an attack by 2000 royalist troops at the siege of Nekmer. Zizka had got his first taste of military life in the war between King Wenceslas IV of Bohemia (now the Czech Republic) and his nobles. He later led his own band of soldiers at the behest of the king in alliance with the southern Poles against the formidable Teutonic Knights. His band was probably present at the battle of Grünwald, otherwise known as Tannenberg, an infamous defeat for the Teutonic Order.

It was his experiences in this campaign that shaped his tactics when he came to lead the Hussite army. He had witnessed the power of the mounted knight at first hand and seen how militia infantry could not stand against them in the open. He must also have been aware of tales from the East, of how the Tartars of the steppes lived and fought from horseback and followed their flocks and herds in their wagon homes on which they carried their portable fortress, or gulai-gurod, which they would circle into a defensive formation when trouble threatened. He would bring these together into the unique Hussite way of warfare.

THE CAMPAIGN

When the religious dissidents first drew together as the Hussites they formed a tented encampment – calling it Tabor after Mount Tabor in the Bible – in the countryside 80.5km (50 miles) south of Prague. Zizka, however, was still in the city with a strong following of Prague militia. After a few days of street fighting he had eliminated all of the royal garrison and Prague was in the hands of the Hussites. Leaving the city in safe hands, he set out for the west, intent on attracting more recruits to the cause.

Meanwhile German Catholics in the eastern city of Kutna Hora massacred the local Hussites, indicating that this was going to be a long, bitter struggle. Zizka became trapped in the western city of Plzen by a force of local Catholics. Unable to risk the arrival of Sigismund and his much larger army he signed a truce with his besiegers and left for Tabor with only 400 men and a train of just 12 supply wagons. The Catholics broke the truce and 2000 men-at-arms attacked him on the march at Sudomer. He drew his small force up with the earth banks of some fishponds on one flank and secured his other flank with the wagons. Although the Catholic men-at-arms dismounted and pressed their attacks until nightfall, they failed and quit the field. Both sides had suffered heavy casualties.

Back at Tabor he set about acquiring weapons in raids on noble residences and building an organized army from the men available. It was here that he started building more of the famous war wagons by converting peasant wagons and crewing them with 16 men and a pair of armoured drivers. Zizka’s army was an army of the people. True, there were a few nobles mounted and armed with lance and shield just like other knights, but these were few in number. Adore numerous cavalry were provided by the lesser gentry, some armed with lances, some with missile weapons and a few armoured with breast and back plate. The great majority, however, were infantry equipped with agricultural tools such as flails, billhooks and axes used as weapons with little modification. ‘They also had one other weapon vital in time of war – grim determination. Convinced of their cause and having seen friends or family burnt for their beliefs, Zizka’s troops would always be formidable opponents. Flight or surrender were never a real option, because they knew they would be massacred.

DISPOSITIONS

In the nick of time Zizka moved the army into Prague (although the castle of Hradcany on the west bank and Vysehrad had been earlier recaptured by royal troops). Medieval Prague lay astride the River Vltava and was dominated on the eastern bank by the hill of Vitkov on which stood an old watchtower. The slopes of the ridge were cleared of any form of cover and the watchtower was reinforced by a strong palisade backing a ditch across the 100m (328ft) wide ridge and flanked by a tower at each end. Its garrison was formed from the Taborites, the most fanatic sect of the Hussite movement.

The inevitable arrived in midsummer; the Emperor Sigismund, at the head of an army of perhaps 80,000 men. The army comprised troops from all over the Holy Roman Empire; there were Bohemians from Sigismund’s feudal lands, plus Germans, Hungarians and others, mostly mercenaries. They made camp on the higher north bank around the village of Bubny. The knights were so well armoured by this time that the shield was becoming obsolete. The feudal contingents were overconfident and arrogant, while the mercenaries, of which there were many, were better trained but more cautious – they wanted to win the battle and return home with their pay. In addition there were mounted crossbowmen and Hungarian cavalry who fought as skirmishers with the bow – a vital and often overlooked role.

This plethora of mounted men was further augmented by feudal infantry with a mixture of melee and missile weapons. the reliance of the Holy Roman Emperor on the Diet, or parliament, to provide money for troops and their unwillingness to ever provide enough, except for his coronation procession to Rome, meant that this army was largely mercenary and paid for with the money provided by the Diet for a lavish coronation by the pope.

Prague could not be safely assaulted with the Vitkov ridge in enemy hands. So Sigismund deployed his bombards at Bubny to the north beyond the river and on the Sickhouse Field, giving them a converging field of fire onto the northern section of wall or onto the position on the ridge, albeit at extreme range.

Zizka knew this was dangerous but could see from the walls that the guns were not closely supported and gambled on a sortie from the Porici Gate, which drove the crews back north over the river and captured a couple of the bombards. This was the first hint of the lax command and control within the army of the Holy Roman Empire. If the guns had been properly supported this sortie could have been disastrous for the Hussites.

DIVERSIONARY TACTICS

For the empire this was just the opening move. The next day Sigismund planned two diversionary attacks, one from Hradcany on the east bank of the city, the other from Vysehrad to the south. Meanwhile, a thousand or more Saxon cavalry under the command of Henry of Isenburg were to launch themselves at the improvised fortifications on the ridge. These were to be followed by an assault by German and Hungarian knights across the Sickhouse Field to storm the gates in the city wall. A good strategic plan – drawing Zizka’s reserves away from the main point of the attack, which was to be delivered with overwhelming force. Unfortunately Zizka wasn’t going to be drawn by the diversions and the poor tactics of the Imperialists in front of the Vitkov palisade fell far short of what was needed.

THE BATTLE

Zizka had foreseen that the Imperialists would attack the palisade on Vitkov first and positioned his first line of reserves between the ridge and the city walls. Since the ridge effectively channelled the Imperialist army to one side or the other this was the ideal spot to cover any eventuality. A second force, led by Jan Zelivsky, was waiting, unseen by the Imperialists, behind the Porici Gate. The ridge assault went in with the men-at-arms dismounting as they got close. Fighting here was fierce, the noise was deafening and confusion was inevitable with too many men and horses trying to assault the palisade. The advancing column must have been 100 men deep while they were mounted, each mounted man requiring a 1m (3ft) frontage. As they dismounted they would have required more space, both to the side to stand and behind for the horse. Ranks behind the first 10 or so would not have known what was happening, or when they were to stop, retreat or go forward. As the front ranks dismounted, those behind had to pass an ever-increasing herd of horses before they could join the fight. However, they did capture the old watchtower, most of the palisade and one of the small forts. The other, garrisoned by a mere 26 men and three women, held out.

COUNTER-ATTACK

Zizka headed out in support at the head of his bodyguard and the rest of the reserves followed. They surged up the southern slope and caught the dismounted and preoccupied men-at-arms in the flank. It is an oft-observed phenomenon that troops engaged in an assault or melee become so focused on their immediate objective that they notice nothing else around them. The inadequate Imperial command and control meant there was no one to warn them or respond to this recent development. The Hussite counter-attack would have taken them completely by surprise.

The men-at-arms, doubtless mingled with many riderless horses, broke and fled down the steep northern slope leaving several hundred casualties behind them. As they came careering down the slope the hidden Hussite reserves sortied from the Porici Gate and attacked the men on the Sickhouse Field. Taking stock of their situation – routing friends and riderless horses coming downhill into their flank and now the enemy uphill besides – these troops too turned and fled in disorder. They were pursued by the reserves under Jan Zelivsky as far as Liben on the banks of the River Vltava. The diversionary attacks were never expected to achieve much and this part of the scheme went exactly according to plan!

THE SIEGE IS LIFTED

Sigismund’s best effort had come to nothing. While he now hesitated, the climate came to the Hussites’ aid. As the Imperial troops sweltered in the hot central European summer with the river at its lowest, disease broke out among them. Money was also running out and bickering over the defeat amongst the leading noblemen did not help. Many mercenaries left the army at this point. Sigismund decided to lift the siege of Prague at the end of July, intending instead to relieve the siege of Wyschrad with just 18,000 men – only to suffer another bloody defeat.

AFTERMATH

Securing the area around Prague meant that the Hussites now had access to one of the most industrially productive areas in Europe. Silver and gold were mined near Kutna Hora; iron and quicksilver near Prague. Zizka took full advantage of this mineral and fiscal wealth and began equipping large numbers of his men with handguns. From the safety of their wagons these wreaked havoc time and again on the Imperialist horsemen. In the end, after nearly a dozen significant battles and despite the urgings of their commanders, the Imperialist troops just would not engage the Hussites again.

The following year, 1421, Jan Zizka was wounded in his good eye during a siege and was blinded. He died aged 64 in 1424. The seeds of the doom of the Hussite rebellion were sown right back at the beginning. From the moment of their triumph over the armies of Sigismund the different factions started to squabble and then split. Five separate parties grouped and split, each with its own aims and agenda. The Taborites accepted only what was stated in the Bible and nothing else. The Orebites or Utraquists – a sect founded by Zizka before his death – lived a more communal life, sharing booty and everything else. They started calling themselves Orphans following his death. The Praguers were held in contempt by the first two for their wealth and worldliness, and they in turn resented the growing independence of the Taborites and Orphans. The rebellion broke into civil war as the factions fought each other.

Eventually, the moderate alliance faced the extremists in battle on 30 May 1434 at Lipany. The extremists were vanquished following a feigned retreat and peace was concluded with the Imperial states. There was another anti-Hussite Crusade from 1464 to 1471. Again the Hussite armies made use of wagons but by then much bigger ones crewed by 18-20 mercenaries each. This last phase was more a campaign of territorial acquisition by the son-in-law of the Bohemian King Georg.

Having lost every battle against the Hussites, Emperor Sigismund went on to be beaten by the Ottoman Turks at Golubac in 1428. Thereafter he left campaigning to his subordinates and died in 1437.