During the 5th, French fighters flew 487 sorties, the highest number on any day of the campaign to date. Even so, it was still far from an all-out effort. Two pilots from GC II/10 flew five sorties during the day, which was the level of intensity the crisis required, but along the entire front, an average of only one sortie was flown for each serviceable plane. It was the most successful day for the French, with pilots claiming fifty-two confirmed victories. In fact, the Luftwaffe lost forty planes, of which twenty-two were bombers. However, nearly all the bombers had been lost in the rear, especially in the fierce clashes with Bloch MB.152s and RAF Hurricanes over Rouen. Over the front, where French troops were under constant attack, French fighters did not have the same success. Curtiss H75s claimed a couple of Henschel Hs 126 observation planes and the Moranes of GC I/6 shot down two Hs 123 ground-attack planes, but that was about it. The Luftwaffe lost just a single Stuka during the course of the day, and this was a victim of anti-aircraft fire. The French fighter force was not succeeding where it was needed. It was low over the battlefield the fighters could make a difference, not deep in the rear over Rouen.

At the end of the day, the French front south of Amiens was still fairly secure. Many of the strong points had been surrounded but these were still holding out. One of the final missions flown by the Air Force was the dropping of supplies to encircled French units to the south-west of Péronne. Further north, the situation was more worrying. South of Abbeville, Rommel had advanced 6 miles against weakening opposition. This was now where air support was urgently needed, but neither Weygand nor Altmayer were aware of how serious the situation was becoming. It seems very few missions were flown by reconnaissance groups, apparently because there were no fighters to escort them. Only two planes from reconnaissance groups were actually lost, and perhaps more should have been risked. The reconnaissance was most needed on the Abbeville sector, not so far from the unused Bloch group defending Rouen. Escorting reconnaissance planes would have been another more useful way of using the Bloch group.

On the 6th, the number of fighter sorties flown fell by nearly a half. Why is not entirely clear, the number of serviceable planes available was about the same as the previous day. French bombers continued to focus on the Chaulnes and Roye area. The lack of fighter cover proved disastrous for the LeO 451 groups. Ten of the twenty-four dispatched failed to return, all the victims of Bf 109s. The escorted Martin 167s, Breguets, and Douglas DB-7s were doing much better, flying around ninety sorties and losing five. The lack of fighter cover did not help but it was also clear to d’Astier that the LeO 451 was simply not a suitable bomber for tactical air support; the American Douglas and Martin bombers were ‘infinitely more suitable’. D’Astier felt that he had no choice but to use the LeO bombers by night, or at least late evening when the gathering gloom provided some cover.

The French fighter force lost sixteen fighters on the 6th, the Luftwaffe fourteen. In the struggle between the two fighter arms, the French might seem to be holding their own. In the context of a long-term battle for aerial superiority, fought independently of ground operations, these losses would not have been cause for too much concern. However, in the context of the battle being fought on the ground, this superficial parity was irrelevant. The German fighter force was enabling the Luftwaffe to operate with freedom. Luftwaffe bomber and reconnaissance losses were negligible. Not one of the Stukas pounding the French was lost. French fighters were not enabling their own Air Force to operate with freedom. German domination of the skies was increasingly apparent to the troops on the ground. A French counterattack by an under-strength 1st Armoured Division towards Chaulnes brought some relief to the defenders, but air cover was totally lacking and Stukas inflicted heavy losses on the tanks.

Even more serious was that French reconnaissance was not picking up the danger further north. By the end of the day, Rommel had reached Poix and was poised to outflank both the Franco-British force holding the River Bresle to the north and the 7th Army still containing the German attempts to break out of the Amiens and Péronne bridgeheads. How many reconnaissance sorties were flown is not clear, but it was not German defences creating an insurmountable obstacle; only one French reconnaissance plane was lost along the entire front. Despite the fierce struggle taking place just sixty miles to the east, the two Bloch units on the Lower Seine remained idle.

On the 7th, most of the 100-odd bombing sorties were again flown in the region around Roye. Although it was becoming clear there was a problem further north, the only French Air Force bomber operation in the area was a raid by half a dozen Martin 167s on German columns north of Poix. By the end of the day, the Anglo-French forces north of the German advance faced encirclement on the coast and the forces further south on the Somme were also having to fall back to protect their flank.

On the 7th, the number of fighter sorties increased to around 300 as the French finally committed the two Bloch groups covering the Lower Seine, but again, Luftwaffe losses were extremely light; only five bombers failed to return. Six French pilots were killed and two wounded, but again, the fighters had failed to break through to the bombers. Ominously, the number of available French fighters dropped dramatically to around 300 as squadrons were forced to abandon bases in the path of the German advance.

By the 8th, the full magnitude of the disaster in the north had become clear to Weygand and d’Astier. Nine Breguet and twenty-one Martin bombers attacked columns heading for Rouen. For the first time, fighters were ordered to join in the attack on a large scale, with forty M.S.406s from GCs I/6, II/2, and III/7 ground strafing enemy columns around Forges-les-Eaux. It was perhaps a day too late. In the late evening, twenty LeO 451s bombed columns south of Péronne, where the line was just about holding. However, French reconnaissance was detecting concentrations of tanks further south along the Aisne, and an attack there seemed imminent. Twenty Breguets and twelve Douglas DB-7s and Martin 167s had to be used to disrupt concentrations around Soissons. Some 100 sorties spread along a 100-mile front was not enough to make a significant difference.

The 8th saw the most intensive use yet of the available fighters with 430 sorties flown from the 300-odd serviceable machines. However, the effect on the Luftwaffe bomber force was minimal. As an interceptor force, the French fighter groups were not having any effect on the course of the battle. In a ground-attack role, they might still make a difference. The floodgates were creaking and it was surely time to throw everything, fighters, reconnaissance planes, anything that could attack the advancing enemy. However, this was not d’Astier’s way of operating. Later, he would make much of the fact that at the end of the battle, his Air Force, unlike the Army, was still a coherent fighting force, but this was not much consolation for a nation humiliated by such a rapid defeat. Nor was it an observation that was likely to be well-received by an Army under constant Stuka attack.

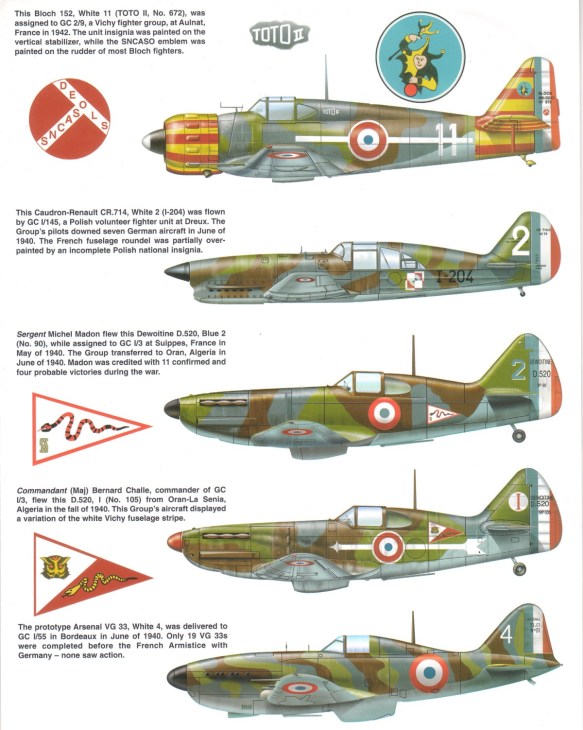

The situation was now disintegrating fast. By the morning of the 9th, the Germans had reached the Seine and Rouen had fallen. In the south, the French had already been pushed back well beyond Soissons. The only good news was that all the bridges over the Seine had been blown and the first task of the German forces on the east bank was to complete the defeat of the Allied forces pinned to the Channel coast. However, on the 9th, the Germans opened the second phase of their offensive along the Aisne. As on the Somme, the French forces resisted fiercely, despite the pounding they were taking from the Luftwaffe. French fighter groups were rushed to the new front. The number on the Aisne front rose to eleven, leaving six on the Somme and four along the Maginot Line. Some 280 sorties were flown but efforts to disrupt the German bombing continued to bring little reward. The Caudron C.714s of the Polish GC I/145 attempted to intercept a formation of Do 17s near Rouen but the Bf 109 escort shot down three Caudrons and another five were forced down with varying degrees of damage. No Dorniers were lost. There were French victories. West of Paris, the D.520s of GC I/3 shot down six Bf 109s for the loss of just one fighter, but along the entire front, the Luftwaffe lost only six bombers. Only in the close escort role were French fighters contributing, but by this time, there were few bombers to escort. The efforts of the previous four days had broken the back of the bomber force. On the 9th, only twenty-seven sorties were flown.

On the 10th, the desperate situation forced the LeO 451s to return to day operations. The French had scraped together 150 tanks for a counterattack south of Rethel, but just eight LeO 451s and nine Douglas bombers could be mustered to support it. These bombed targets 5–10 miles ahead of the advancing French tanks. It was the best that could be organised in the circumstances, but such limited resources would have been more useful against the inevitable improvised anti-tank screen that once again halted the French advance. As was the case in the very first days of the campaign, when the French were trying to recapture the Moerdijk bridge in the Netherlands, this was where a small number of bombers might make a difference. The Breguet bombers in the Rif campaign might have been able to deliver, but such close coordination could not be recreated overnight.

The remaining twenty-odd bomber sorties flown that day concentrated on the German forces already advancing well to the south-west of Reims, and the bridgeheads the Germans were already establishing across the Seine. Six ground strafing Bloch MB.152s of GC I/8 took part in the attacks on the latter, the first time the Bloch had been used for ground-attack since 18 May. Again, no Blochs were lost, but this second experiment was not repeated. German fighters were constantly strafing French airfields and any other targets they came across, but this was not how d’Astier wanted to use his fighters.

By the end of the 10th, the position seemed hopeless. The Aisne line had been punctured and the forces did not exist for a serious attempt to hold the Seine. On the 11th, Paris was declared an open city and the following day, Weygand ordered his battered armies to pull back to the River Loire. The Air Force tried to buy the Army some time. Eighteen Breguets bombed bridges the Germans were constructing over the Seine at Les Andelys and Vernon while twenty-one LeO 451s attacked columns around Rethel. On the 12th, thirty-one Martin 167s bombed columns already advancing beyond Reims. On the 13th, an all-out effort was made by fifty bombers to slow down German forces sweeping past Montmirail and overtaking the retreating French forces. Even Amiot 354s, still without bombsights, were used in low-level evening attacks, but only aircraft from regular bomber groups were being used in these desperate efforts to slow down the German advance.

Most now believed the only serious military option was to evacuate as much equipment and as many men as possible to North Africa and continue the war from there. Even this became problematic when, on 10 June, Mussolini decided that the time had come for his country to take advantage of France’s predicament. Fortunately for the French, the Italian entry into the war was more a political gesture than a military threat and the weak French forces remaining in the south were able to hold the half-hearted Italian attempts to advance along French Mediterranean coast.

The Panzers did not cross the Seine until the 16th, but east of Paris, eight Panzer divisions were streaming south. The rapid retreat forced squadrons to abandon equipment and unserviceable planes. By the 13th, the French only had around 150 serviceable fighters. The only protection French troops now received was from the weather, which fortunately was severely hampering the operations of both sides. By the 16th, the Germans had already reached Dijon, effectively cutting off the line of retreat of units belatedly pulling out of the Maginot Line.

The mighty French Army was doomed, but the Air Force had the mobility to flee and fight another day. Although battered and bruised, the force still had enormous potential. Losses in aircrews had been no heavier than those suffered by the RAF, and the survivors were now battle-hardened veterans of enormous value to the Allied cause. They might yet play a crucial part in North Africa and even in the battle that would surely follow in Britain.

French confidence was already being restored by the first clashes with the Italian Air Force. French pilots soon discovered that the technical superiority of planes like the D.520 over the Italian Fiat CR.42 was as great as the German Bf 109E over the M.S.406. With production facilities in France lost, the French Air Force would have to rely entirely on American imports, but these were already arriving in some numbers and the evacuation of existing stocks of planes should enable units to remain operational on French types for a while.

On the 16th, a full-scale evacuation of the French Air Force began. Groups equipped with planes like the M.S.406 and MB.152 that lacked the range to cross the Mediterranean, would continue to cover the remnants of the French Army. The five Breguet 693 groups along with three LeO 451 units and two Amiot 143 groups, also stayed, together with four reconnaissance and twenty observation squadrons. Other units made their way to North Africa with whatever equipment they possessed or could lay their hands on. Many brand new machines were picked up direct from factories and flown straight to North Africa without so much as a test flight. On occasions, pilots were actually flying that particular type for the first time. Ferry pilots, instructors, and partially trained students all managed to fly valuable combat planes out of the country. Even General d’Harcourt flew a D.520 out. By the end of June, some 700 modern aircraft had been flown across the Mediterranean. With 300 modern planes already in North Africa, there was more than enough to keep the fourteen fighter, twenty-two bomber, and nine reconnaissance groups based there operational for a while. Doubtless far more equipment and personnel could have been evacuated, yet this was not to be. On the 22nd, the French government accepted peace terms offered by the Germans and two days later, a treaty was signed with Italy. Fighting officially ended on all fronts at 12.25 a.m. on the morning of the 25th.

Until the very end, those Air Force units that remained in France continued to oppose the German advance. At Cherbourg, French naval units, including ponderous LeO 257 floatplanes operating by day, flew against the panzers advancing on the port, but could not prevent its fall on the 19th. In the south, when weather permitted, the Breguets and LeO 451s continued to fly against German and Italian targets. On the 23rd and 24th, in one last defiant gesture, all fighter units were ordered to ground strafe German columns advancing down the Rhône valley. Three weeks earlier, such a bold move might have been more than a mere gesture. The last French victory was a Henschel 126 shot down by a pilot of GC I/2 on 24 June and the last French Air Force casualty was suffered just hours before the Armistice came into effect when S/Lt Raphenne of GC I/6 was shot down and killed while strafing German panzers just north of Valence.