On the ground, Weygand had few options. With the Luftwaffe controlling the skies, the last thing the French wanted was a war of manoeuvre. Even a limited retreat from the position they now held might prove catastrophic. Weygand opted for a static defence in depth, with towns and villages turned into strong points and their garrisons instructed to hold on, even if bypassed by German forces. By holding key communication centres, the French hoped that the panzer spearheads would be starved of supplies and that the German offensive would eventually fizzle out. In the circumstances, it was the strategy which offered the French the best chance of success.

Weygand’s policy was not entirely defensive. If the French could recapture bridgeheads the Germans had established at Abbeville, Amiens, and Péronne, it would boost French morale and make the German task more difficult. With the Germans fully occupied around Dunkirk, there would be no better time. There was now a new-found determination to integrate bomber support with operations on the ground. Georges wanted these counterattacks supported by ‘rigorous bomber action’ and Weygand demanded the maximum bomber effort against the panzers forces assembling in the bridgeheads. Vuillemin, Weygand, Georges, and Têtu all now agreed on the need for bomber support on the battlefield.

On the 26th, the four Breguet 693 groups and two fighter groups—GC III/2 and GC III/3—were made available to General Frère’s 7th Army to support attempts to eliminate the German bridgeheads at Amiens and Abbeville, where de Gaulle’s 4th Armoured Division was in action. This Assault Brigade and its accompanying fighter groups were, in effect, now being used in much the same way as the Air Division of the First World War. To speed up the response time, flights of fully armed Breguets, with their engines ticking over, were kept on alert at forward airstrips ready to intervene immediately an appropriate target was identified, a practice a previous generation of Breguet tactical bomber units had used in the Rif campaign. Poor weather limited the opportunities of the brigade, but about forty sorties were flown against various targets in and around Abbeville and Amiens in the last four days of May. Four Breguets and Potezs were lost, all the victims of fighters.

The last day of the month proved to be a particularly unfortunate one for the entire bomber force. Nine out of twenty-one LeO 451s were lost, as were four out of twelve Douglas DB-7 bombers and two out of eighteen Martin 167s, again all the victims of fighters. Weygand wanted the German bridgeheads pounded with everything the Air Force had and demanded that these attacks should continue but Vuillemin feared that his force would be exhausted before the Germans even launched their offensive. In the end, a compromise was worked out whereby the light and assault bombers continued to provide the Army with support by day, while the LeO 451 groups would operate by night until the Germans attacked, although following the heavy losses of the 31st, no missions would be flown until the night of 4–5 June.

Meanwhile, the counterattacks on the German bridgeheads across the Somme were continuing. General Altmayer’s 10th Army had now taken over the Abbeville sector of the Somme front. On 3 June, the Assault Brigade with forty-three Breguets and forty fighters, was put at his disposition, for a further assault on the Abbeville bridgehead planned for 4 June. The army commander was also told that a further fifty bombers and 100 fighters were available for more general support. ‘What am I to do with all this aviation? I’ve already got more than sufficient artillery,’ he is reputed to have replied. Altmayer made no attempt to call upon the resources put at his disposal either before or during his counterattack. Altmayer can hardly be blamed. The Army had always insisted bombers did not have an important role to play on the battlefield. At the top of the Army command structure, Weygand and Georges may have come to appreciate that ideas had to change but it was expecting a lot of Altmayer to enthusiastically embrace this use of air power overnight. Although the French counterattacks reduced the size of the German bridgeheads, none were eliminated, so strategically, the attacks were failures.

While the French troops along the Somme and Aisne awaited the German offensive, in the rear, a threat of a different kind was causing far more concern. On the first two days of June, the Luftwaffe launched a series of powerful raids against targets in the Rhône valley, including industrial targets around Lyon and the port of Marseilles, where reinforcements were arriving from North Africa. It was a timely reminder to the French that they dare not reduce their aerial defences in the rear. Even more disturbing was the mounting evidence that the Germans were planning a major air assault on the French capital. For Parisians, this was a much greater threat than the panzers just sixty miles away. For Vuillemin too, the danger was still in the rear. On 29 May, he made it very clear to d’Astier that the defence of Paris had to have priority over support for the armies at the front.

The danger to Paris was far more acute than it had been a few weeks before. The Germans were not quite as near to Paris as they had been in 1918, but the speed of modern bombers meant that the capital was little more than fifteen minutes flying time from the front. Before 10 May, the Bf 109E had not been capable of reaching the Paris area; now, it could escort German bombers all the way with ease. With the world still stunned by the destruction of Rotterdam, the French believed they had good reason to be worried. For French civilians and government, the moment of truth was at hand.

French intelligence was correct. ‘Operation Paula’ was never intended as a pure terror raid—the targets were military rather than civilian—but the Germans hoped an attack on Paris would shake French morale. Targets included communication centres, airfields, and factories. Targeting factories scarcely suggested that the German High Command were entirely convinced they would soon be in their hands. About 500 German bombers, escorted by an equal number of fighters, would take part in the raid.

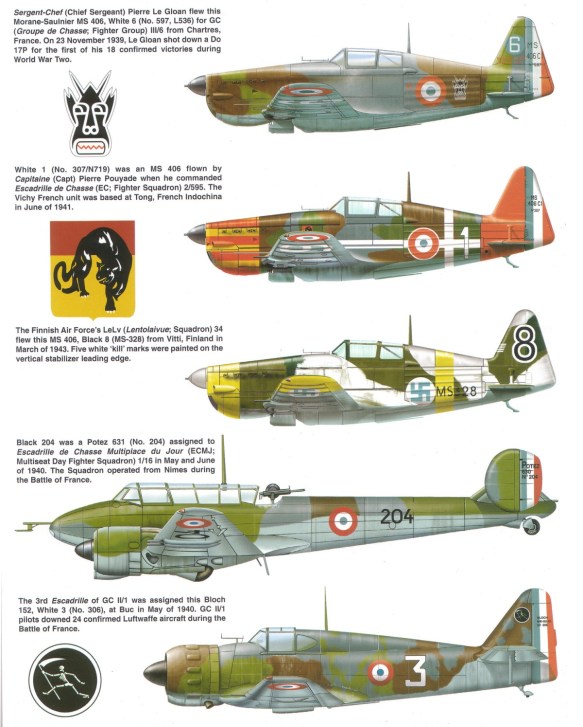

For some time, both Groupements 21 and 23 had been on standby for the expected Luftwaffe attack. Groupement 22 in the east had also been told that it should try and intercept German formations as they headed back towards Germany. The Potez 631 squadrons would try and follow the bombers and report their positions. Ground controllers, using the Eiffel tower radio mast, would transmit instructions to the fighter squadrons. The Dewoitine D.520 groups would tackle the German escorts, while other fighters would concentrate on the bombers. With only fifty serviceable Dewoitine D.520s, it was a daunting task.

Soon after midday on 3 June, the raids began on targets in and around Paris as well as airfields well beyond Paris. The Potez 631s did what they could but the scrambling fighter squadrons were always going to be desperately short of time and their task was complicated by the Germans jamming the instructions from the ground controller. GCs III/1 and II/1 both had to take off amid falling bombs. GCs I/1 and II/9 were both caught by enemy fighters as they climbed towards the bombers and eight of their Bloch fighters were shot down. The Moranes of GC III/7 once more found they lacked the speed to catch the German bombers, and were then set upon by German escorts. By good fortune, the arrival of the Dewoitines of GC I/3 enabled them to escape. GCs I/5, I/6, and I/8 spotted bomber formations but found it difficult to break through the German escorts. To the west of Paris, three Polish pilots from GC I/145, flying their unsafe Caudron C.714s, entered the fray claiming three Bf 109s, but they too failed to get through to the bombers. Four pilots from the Belgian Air Force unit GC II/2, still flying their Fiat CR.42 biplanes, gamely attempted to stop Do 17s attacking their airfield at Chartres, and contributed to five of the attacking Dorniers returning badly damaged. Seventeen French fighters were lost, thirteen pilots were killed, and eight were seriously wounded. They claimed seventeen certain victories, although the Luftwaffe lost just seven fighters and only four bombers. In the air, it was another emphatic victory for the German fighter force.

However, the raid itself achieved little. Only five aircraft were destroyed and four damaged at the thirteen airfields bombed. About 250 Frenchmen lost their lives in the attack. While heavy, these casualties were not on the cataclysmic scale predicted by so many experts before the war. There was no panic or public disorder in the streets of Paris and no extra pressure on the government to seek an end to the war. The threat that had dominated and distorted French thinking for two decades had finally materialised, and while it was by no means an empty threat, it was far more manageable than the prophets of doom had predicted. In the overall scheme of things, the much-feared bomber threat turned out to be irrelevant. The fate of France would be decided on the Somme and Aisne battlefields, not in the skies above her cities; on those battlefields, the Army would need the cheaper light bombers that could have been built instead of large expensive planes that the long-range deterrent bomber force required.

This was still not so easy to see at the time. It was not easy to switch mindset in a matter of days. The Paris raid and others in the rear ensured the French still kept back strong fighter forces. The principal task of four Bloch groups and GC I/145 remained the defence of the capital and Lower Seine. At Lyon, there was a semi-operational Polish group created from pilots awaiting transfer to front line squadrons, which offered some protection for the area, but it was still felt necessary to keep GC III/9 there. GC II/7, one of the few Dewoitine D.520 groups, and GC II/2 were based well to the south of the Aisne line, covering the Dijon and Tours regions. GC III/6, converting to the Dewoitine D.520, provided some protection for Marseilles, but it was still felt necessary to have GC III/1 there too. More than twenty light defence flights were also covering targets in the rear.

There were good reasons for covering the rear. Reinforcements arriving from North Africa via Marseilles were very worthy candidates for protection and the desperate shortage of planes made it difficult to leave aircraft factories undefended. Nevertheless, it was not in the rear that the fate of France would be decided. If the front line held for a week and every French factory in the rear had been destroyed, France would still be in the war. If the line did not hold, it did not matter how many factories were building aircraft. Indeed, if the Luftwaffe could be persuaded to bomb French factories rather than the French Army, France’s chances of survival would be considerably improved. It was a mistake the German High Command was unlikely to make. Guarding against this potential threat, however, was also a mistake. The French could not understand why, at such a critical stage, the British were holding back 600 fighters in the UK to meet an attack that had not so far materialised. France had more reason to fear bombing attacks—her cities and towns were being bombed—but they were just as guilty of holding fighters back. To survive, the French had to take chances, and one chance was to leave the rear exposed and focus all air effort on holding the front line. French fighter units were not well placed to do this. Once the German offensive was underway, the French would have to get as many fighters over the front as quickly as possible, if they were to have any chance of halting the Wehrmacht juggernaut.

As far as retaliation was concerned, the French were not quite as helpless as they had been in 1918. All medium and heavy French bombers had been designed with Berlin in mind as the principal target. Ironically, now that retaliation was required, they were far too valuable tactically to squander on a long-range bombing offensive. The two Farman F.222 groups were ordered to bomb Munich and seven sorties were flown on the night of the 3rd–4th.26 The following night, seven LeO 451s joined four Farmans for a second attack on Munich. Retaliation against the German capital itself was left in the hands of the Navy. Its sole Farman F.223.4 long-range reconnaissance bomber had the remarkable ability to carry 2,000 kg of bombs along the Channel, North Sea, and Baltic coasts and then south to Berlin. The Germans were taken completely by surprise, both by the raid itself and the direction from which it came. There were no blackout precautions and the French crew found their target with little difficulty.

The raid was only a gesture, but this was all that was required. The next day, the French press were able to lift the morale of the nation with a slightly exaggerated account of how a formation of naval bombers had struck the German capital and neutral embassies were certainly able to confirm an attack had taken place. After all the effort that had gone into the creation of a bomber force capable of attacking the German capital, a single long-range bomber, and a naval one at that, was all that was needed to satisfy French honour.

Meanwhile, the Germans were preparing to launch the offensive that would decide the fate of France. French reconnaissance planes did a fairly good job of identifying where the Germans were concentrating for the attack. It seems only around a dozen sorties a day were flown, and with fighters on standby to meet the expected attack on Paris, most of these missions were unescorted, but only four reconnaissance planes lost in the first four days of June. The densest concentrations of tanks were identified in the Péronne region with smaller groupings spotted around Amiens. With these threatening Paris directly, there was little doubt in French minds that this was where the greatest danger lay.

The German plan did not involve any great tactical or strategic novelty. The ten available German panzer divisions were divided equally between the five proposed lines of advance. On 5 June, three of these would strike westwards from Abbeville, Amiens, and Péronne. The French would be forced to commit their reserves to counter these thrusts. Then, after three days, the Germans would use their remaining two armoured corps to strike south across the Aisne from the Rethel region.

The German attack again involved intensive use of level and dive-bombers over the French front line, but this time, there was no repeat of the panic on the Meuse. The French troops now knew what to expect and tenaciously resisted the German advance. All the available light and assault bombers were thrown against the advancing panzers. The sixty-eight Breguets, Martins, and Douglas bombers focused their efforts on the roads leading west from the Péronne bridgehead southwards to Chaulnes, but when fighter escorts were not available, the results were disastrous. An escorted early morning strike by ten Breguets suffered no losses but a second strike at 9 a.m. was savaged by Bf 109s, with nine out of the twelve Breguets shot down. A formidable force of D.520s, Bloch MB.152s, and H75s was assembled to cover more Breguet attacks in the afternoon and evening. The fighters did their job, and no more Breguets were lost. Twelve ground-strafing Moranes joined these attacks, losing two to ground fire, but it was still a tactic Vuillemin was very reluctant to use.

As soon as it became clear the northern front was bearing the brunt of the new offensive, four fighter groups (GCs II/2, II/5, II/7, and II/6) were ordered to support the fighters on the Somme front. GCs II/2, II/5, and II/7 were heavily involved in the afternoon escort missions, the Moranes of GC II/2 joining in the strafing attacks. GC II/6 at the Châteauroux Bloch factory did not get involved over the front until the next day. The Bloch groups defending Paris were operating over the front but both GC II/10 and III/10 were held back to cover the Lower Seine. This was now much closer to the fighting than it had been on 10 May, but it was not where the fate of France was being decided. GC II/10 was in action, shooting down three Heinkels in an early morning raid on Rouen and a couple of Ju 88s in an evening raid, but GC III/10 did not encounter a single German plane throughout the course of the day. It was not sensible to have a fighter group idle while an unescorted Breguet attack was being decimated by Messerschmitts.