The rise of the Parthian Empire in the second century BC was connected with the Mediterranean expansion of the Roman regime. When the Seleucid King Antiochus III came to power in 222 BC, he campaigned in Parthia and Bactria to regain his authority over these distant territories. Antiochus also expanded Seleucid rule into western Asia Minor and made plans to annex the Greek city-states around the Aegean that were either semi-independent or under the rule of rival Hellenic kings. In 192 BC Antiochus invaded Greece with an army of 10,000 soldiers and the support of a federation of Greek states called the Aetolian League. This invasion brought the Seleucid Empire into conflict with the militarized Roman Republic and its formidable network of Italian allies. The Romans mobilized over 20,000 soldiers and after defeating the Seleucid army at Thermopylae, they pursued Antiochus into Asia Minor and sent a fleet to attack his naval forces. The decisive battle in this war took place in 190 BC at Magnesia in western Asia Minor. According to Livy, the Roman legions achieved a battlefield victory with a force of 30,000 soldiers while facing a Seleucid army consisting of about 70,000 fighting men levied from all parts of their extensive realm.

In 188 BC Antiochus III was forced to conclude a peace settlement with Rome that required all Seleucid forces to withdraw from Greece and most of Asia Minor. Seleucid armies were dependent on Greek mercenaries, but Rome prohibited the regime from recruiting new troops from any territories under Roman protection. The Romans also demanded war reparations from the Seleucid Kingdom to be paid in silver bullion. The annual figure was set at 1,000 talents (almost 26 tons) which was enough silver to mint 6 million Roman denarii. To give context to this figure, by the first century a denarius represented a generous day’s pay for a labourer. This income greatly increased Rome’s capacity for war, while stripping the Seleucid kingdom of the wealth and revenues it relied upon for its own stability. The loss of this income diminished Seleucid funds for employing soldiers, maintaining garrisons, hiring labour and purchasing foreign resources such as shipbuilding materials.

After its defeat by Rome, the Seleucid Kingdom began to disintegrate through a series of dynastic conflicts, local revolts and civil wars supported by rival powers. The Seleucid Empire finally collapsed when mounted Parthian armies attacked from its eastern flanks to invade Media and seize power in Babylonia (141 BC). In 138 BC, the Seleucid King Demetrius II Nicator was defeated in battle and taken as an ‘honoured captive’ to the Parthian capital Hecatompylos in eastern Iran. Meanwhile, his brother Antiochus VII Sidetes assumed the Seleucid throne in Syria and prepared a large force of Greek mercenaries to retake Babylonia. Ancient accounts claim that his army included 80,000 armed men which represented the largest force that the Seleucid regime had been able to assemble for several generations.

Attacking in 130 BC the Seleucid army successfully retook Babylonia from the Parthians. But Seleucid soldiers imposed heavy requisition burdens on some Iranian communities and their actions encouraged pro-Parthian uprisings. During these disturbances an army of Parthian horsemen crossed undetected into Media and when the Seleucid King Sidetes entered the territory with his royal guard, he was intercepted and killed. The leaderless Seleucid army was expelled from Babylonia and the Parthians prepared to conquer Syria and extend their empire west towards shores of the Mediterranean Sea. But the campaign had to be abandoned when Saka war-bands from the Central Asian steppe attacked the Parthian homelands in eastern Iran.

Babylonia contained densely populated cities and its conquest brought immense wealth into the Parthian Empire. The walled city of Seleucia on the Tigris River had a population of up to 600,000 people which included Greeks, Jews, Arabs and Persians. It had been one of the primary capitals of the Seleucid Empire and by the first century BC it was perhaps the third largest city west of India. In an effort to dominate Babylonia and further enforce their rule, the Parthians established their own royal capital named Ctesiphon on the banks of the Tigris, opposite Seleucia. Ctesiphon served as the western capital of their enlarged empire and the Parthian King spent the winter administering his realms from palaces in this monumental city. But every year before the onset of the hot and humid summer months, the king moved his royal court east to the cooler higher-altitude climate of Ecbatana where meadow greenery covered the hillsides around the ancient Iranian city.

The Han Empire established its first diplomatic contact with the Parthians in about 100 BC. They called the regime Anxi since the Parthian founding dynasty was known as the Arsacids. The Shiji records that when the first Chinese envoys arrived on the eastern frontiers of Parthia they were greeted by a ceremonial guard of 20,000 horsemen. They were escorted ‘several thousand li from the border and passed through several dozen cities inhabited by great numbers of people as they travelled to the capital [Hecatompylos].’ The Parthian King Mithridates II (121–91 BC) reciprocated by sending his own envoys to China to ascertain the size and power of the Han Empire. The Parthians sent the Han Emperor unusual gifts from their homelands including court conjurers and ostrich eggs.

Chinese records from this period describe the Parthian Empire as ‘by far the largest kingdom’ and report that it possessed ‘walled cities like the people of Dayuan [Ferghana] in a region containing several hundred cities of various sizes’. Even in this early period Parthia had long-range commercial networks, and the Shiji reports ‘some of the inhabitants are merchants who travel by carts or boats to neighbouring countries, sometimes journeying several thousand li’ (1,000 li = 310 miles). The Chinese also took an interest in Parthian coinage, noting that ‘the coins of the country are made of silver and display the face of the king. When the king dies, the currency is immediately changed and new coins issued with the face of his successor.’

First Contacts with Rome

During the second century BC the Roman Republic conquered the Kingdom of Macedonia and achieved full authority over ancient Greece. Then in 133 BC the Romans were bequeathed the small kingdom of Pergamon and the Republic gained a permanent presence on the Aegean coast of Asia Minor. This was the beginning of the Roman expansion into western Asia.

The first diplomatic contact between Rome and Parthia occurred in 97 BC when a general named Lucius Cornelius Sulla restored a deposed ruler to the throne of Cappadocia in eastern Asia Minor. Cappadocia was confirmed as a Roman protectorate and during these operations Sulla led imperial forces as far as the River Euphrates. On their arrival there, the Roman army received a Parthian envoy who had come to investigate recent political events and ‘seek the friendship of the Roman people.’

Sulla did not refer the matter to the Roman Senate and insulted the Parthians by arranging that their envoy take a submissive position close to the Cappadocian king in a publicly staged political meeting. The envoy was escorted to a chair beneath that of the Roman general in a scene that suggested that the Parthians were a foreign power subject to Roman dictates. But Parthian rule was dependent on maintaining authority over subject realms and when the Parthian king received news of this public dismissal, he ordered his envoy executed for defaming the regime.

In 66 BC the Senate sent Gnaeus Pompeius (Pompey) to take charge of the Roman forces campaigning in Asia Minor. Pompey renewed the existing agreements with the Parthian Empire that promised non-aggression, non-interference and possibly acknowledged the Euphrates as the frontier between their domains. Pompey then added a large part of Asia Minor and Syria to the Roman Empire and formed political intrigues with vassal rulers under Parthian dominion. This broke the terms of the existing treaty, but when Parthian envoys asked the general for an explanation, Pompey replied that ‘he would observe any frontier that seemed fair to him.’

These Roman conquests in western Asia gave the imperial government access to enormous new revenues. In 61 BC Pompey returned to Rome to celebrate his achievements with an elaborate triumphal parade through the centre of the capital. Written records were displayed to the Roman public showing how the new conquests had added 140 million sesterces to Republican revenues previously worth about 200 million sesterces per annum (50 million denarii).

In this era it seemed possible that the Romans might claim all the territories that had once formed the Seleucid Kingdom. Many of the urban communities in Babylonia were still recognisably Greek and the Romans saw themselves as the natural successor to that civilization. These Greek communities paid regular tribute to the Parthian Empire in order to preserve a degree of localised political freedom and self-governance. But they could be antagonistic towards their Parthian overlords and might support Roman interests if the opportunities seemed favourable.

A Roman pretext for intervention came in 58 BC when the Parthian king Phraates III was murdered and his sons fought a civil war for control over his empire. One of the sons fled to Syria where he sought military assistance from the Roman governor Aulus Gabinius (57–55 BC). The sources suggest that Gabinius was prepared to support this Parthian prince with an invasion force that would seize the western capital Ctesiphon. But then Gabinius received a payment from the Ptolemaic king Ptolemy XII Auleles, who needed urgent Roman support to crush a rebellion in Egypt. Auleles is said to have offered Gabinius 10,000 talents (240 million sesterces) for his immediate assistance and his needs took precedence over Roman plans to seize Ctesiphon.

Crassus and the Battle of Carrhae

In 58 BC Julius Caesar began the conquest of Gaul which extended the Roman Empire north as far as the Rhineland and the coasts of Europe facing Britain. Meanwhile, his political ally Marcus Licinius Crassus was allocated the governorship of Syria and prepared for the conquest of Babylonia. Crassus had gained military honours by brutally suppressing a major slave revolt in Italy led by a former gladiator named Spartacus (71 BC). By 55 BC he was the richest politician in Rome, but he craved the wealth and glory of foreign military conquests that would equal or exceed the achievements of his colleagues Pompey and Caesar. Crassus therefore planned to emulate Alexander by invading Persia before leading his conquering armies east to the frontiers of India.

The Roman conquest of Persia seemed feasible since the Republic had overcome all rival powers in the eastern Mediterranean, including the Greek and Macedonian successors of Alexander. As Livy claimed, ‘The Romans have repulsed a thousand armies more formidable than those of Alexander and his Macedonians and if the peace is broken, they will do so again.’ The steppe armies of the Parthians seemed to be a manageable opponent since in 68 BC the legions led by a general named Lucius Licinius Lucullus had easily defeated mounted archers and armoured cataphracts in Armenia at the Battle of Tigranocerta. In this battle, Lucullus ordered his lightly-armed auxiliary cavalry to charge the Armenian cataphracts and keep them occupied while several hundred legionaries rushed forward to surround their position. The legionaries were instructed to strike at the unprotected legs of the armoured horses causing the riders to tumble from their heavy mounts. Plutarch explains the Roman soldiers commanded by Crassus ‘were fully persuaded that the Parthians were the same as the Armenians and the Cappadocians, whom Lucullus had robbed and plundered till he was weary of the effort. They thought that the most difficult part of the war was going to be the long journey and the pursuit of an enemy who would avoid close quarter fighting.’ However, Plutarch claims that many Roman politicians opposed a conflict with Parthia because ‘they were displeased that anyone should wage war on men who had done the Roman State no wrong and were held in established treaty relations.’

When Crassus took command in Syria in 54 BC, he sent Roman troops into northern Mesopotamia to claim several frontier towns on the Upper Euphrates. Greek communities from the walled cities of Babylonia also sent spokesmen into Syria to negotiate terms with the Romans and offer them support against the Parthians. As Crassus awaited the arrival of reinforcement Roman cavalry from Gaul, he spent his time reviewing the revenues and treasury reserves of subject populations in Syria and Palestine.

Crassus sent word to the Armenian King Artavasdes II requesting allied troops for his planned conquest of the Parthian Empire. But Artavasdes cautioned Crassus not to invade Babylonia via the northern Euphrates, as this meant crossing desert plains where the Parthian cavalry had an advantage over Roman infantry. He urged the general to proceed through Armenia and Media where rugged terrain would impede the Parthian horsemen. The Armenians offered to provide abundant supplies and significant military support to Roman forces using this route and Artavasdes pledged 6,000 royal horsemen, 10,000 armoured cavalry and 30,000 infantry to assist the legions. Crassus rejected the offer, perhaps reasoning that the Euphrates River Valley would provide a more direct invasion route into the Parthian domain and offer better supply and communication lines for the Roman advance. He expected the Greek cities of Babylonia, including Seleucia, to support the Roman cause and when he captured the Parthian capital at Ctesiphon, this would provide him with greater wealth and glory.

In the summer of 53 BC, Crassus led an army of 40,000 Roman troops across the Euphrates frontier into the territory of the Parthian King Orodes II. This Roman force was almost the same size as the army that Alexander led to victory against the Persians almost three centuries earlier. Crassus commanded seven legions consisting of 35,000 armoured infantry, 4,000 light-armed auxiliaries, 4,000 cavalry and 1,000 Gallic horsemen sent by Julius Caesar.³² The cavalry forces were under the command of Crassus’ son Publius, a well-respected leader who had served with Julius Caesar in Gaul.

Crassus had high expectations of success, but even before the campaign began, disturbing reports reached the Romans regarding Parthian tactics and armaments. Roman garrison troops posted in northern Mesopotamia reported that during the winter they had been attacked by Parthians riders equipped with arrows that could pierce through any protective armour. The reports suggested a type of missile-weaponry that was superior to any previously encountered equipment, but Crassus dismissed these claims as ‘exaggerated terror’.

Further concerns were raised when the legions crossed the Euphrates River. Crassus was met and challenged by a Parthian envoy named Vageses who accused him of being led by greed to cross the agreed boundary between their empires. Vageses warned Crassus that he was breaking political treaties agreed by previous Roman generals and if he continued with an invasion in search of Parthian gold ‘he would instead find himself burdened with Seric iron.’

The term ‘Seric iron’ would not have alarmed Republican Romans who knew little about the distant Seres or ‘Silk People’. In this era the Romans were unaware that the Parthians were connected to an overland supply chain that was equipping their warrior-horsemen with superior armour and weaponry. Small samples of Chinese silk had probably reached the Mediterranean soon after the Han Empire secured the Hexi Corridor and established a route through the Tarim territories (104 BC), but during this period supplies of superior oriental steel were highly-prized by steppe peoples and this metal was not reaching markets in the Mediterranean in any great quantity.

As Crassus began his march down the Euphrates Valley, reports arrived that the main Parthian army had crossed from Media into Armenia. The Parthian King Orodes II probably hoped to distract Crassus from his invasion route by threatening Roman interests in the allied Armenian kingdom. But Crassus ignored Armenian requests for assistance in favour of continuing his planned attack on Babylonia. He probably reasoned that, with the Parthian king and main army absent in Armenia, the territory would be poorly defended.

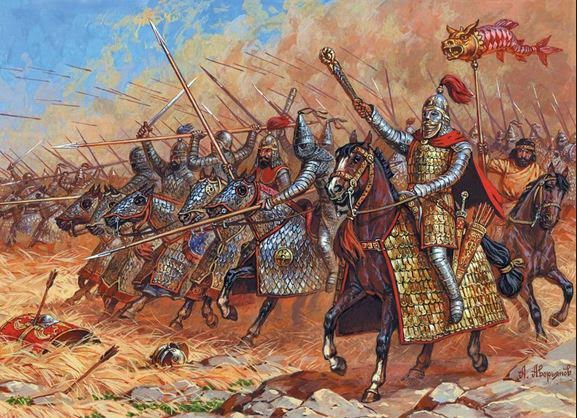

King Orodes had left the defence of Babylonia to a Parthian prince named Surenas who had raised a force of horsemen from his subject realms in eastern Iran. Orodes knew that Surenas could harass and delay the Roman invasion, while the main Parthian forces made military gains in Armenia. But Surenas planned a full engagement with the Roman army using the well-known strategies and ambush tactics of steppe warfare. His force was small, highly mobile and carried steel-enhanced weaponry including lances, armour and arrowheads.

Surenas was in command of approximately 9,000 lightly-armed mounted archers and 1,000 heavily-armoured cataphracts. These mounted lancers wore steel-strengthened mail-clad armour with conical-style plumed helmets with their warhorses protected by a blanket of chain mail. The archers carried composite horn and wood bows and wore belted tunics, wide trousers and long riding boots that allowed fast flexible movement. To provision this mounted battle-force, Surenas brought his personal caravan of 1,000 camels. By comparison the Roman infantry force were equipped with chain mail shirts, cap-like protective headgear, large oval wooden shields, short-swords suited for stabbing and several weighted javelins for single-use ranged attack. The spear-equipped Roman cavalry carried large shields and were armoured with mail shirts and helmets. Crassus had not made any arrangements for supply columns to replenish his stock of spent weaponry.