“Richard the Lionheart, Battle of Arsuf, 1191” Justo Jimeno Bazaga

The battle of Arsuf fitted a Crusader army under Richard the Lionheart against a Saracen force under Saladin. It was a severe test of the discipline that Richard hoped to instill in the Crusader armies. ultimately, the crusader infantry proved their worth in the face of constant harassment by Muslim cavalry.

The Crusader armies tended to be an ill-assorted mix of troop types and fairly undisciplined. The backbone was provided by mounted men-at-arms and nobles from the Christian kingdoms of Europe. Armoured in chain mail and an open-faced metal helm, the man-at-arms was trained to war all his life. His sidearm was the long sword, but he might also carry an axe or mace as well as his shield and lance. Knights, noblemen and men-at-arms came to the Crusades from all across Europe. The most famous groups were the Knights Templar and the Order of St John (the Hospitallers).

WARRIOR MONKS

The Knights ‘Templar, otherwise known as the Poor Fellows of Christ, were formed after the First Crusade (1096-99) in response to a need for fighting men to defend the conquered lands. Chaining papal approval in 1120, they were an order of warrior monks who took vows of poverty and chastity and lived according to a very strict code. They wore the white surcoat of their order over a plain and unadorned chain mail shirt called a hauberk, along with a mail coif (hood) and leggings. Their helm was plain and open-faced, similar to that worn by Norman knights at the Battle of Hastings. Under the mail hauberk was a padded jerkin to absorb the impact of blows.

The Templars have become the symbol of Christian knights. They were fearsome and unrelenting in combat against their Muslim foes, believing that death in battle against the enemies of Christendom was a direct route to heaven. The Templars had a fierce rivalry with the Hospitallers that did at times turn violent. Each order had an agreement not to accept men from their rival order.

The Knights of St John began as a charitable order sometime in the 1070s. Their goal was to care for pilgrims to the Holy Land. Booty from the First Crusade, donated to the order, paid for a chain of hospices across the region. Eventually the order took on the duties of protecting the pilgrims and the city of Jerusalem, and became a militant order. Using mercenaries and knights friendly to the order, the Hospitallers garrisoned several fortresses on the route to Jerusalem. After the Crusader army was destroyed at Hattin in 1187, the pope decided to support the various military orders and gave his blessing to the Hospitallers’ military role.

THE CAVALRY CHARGE

There is much debate about exactly when the mounted warrior began to charge with the couched lance, i. e. with his weapon held under the arm and braced for a head-on impact. At the time of the Battle of Hastings (1066), some Norman knights were using the lance this way while others thrust downwards with it overarm or rode past and speared enemies out to the side from beyond the reach of their weapons. Some men are known to have hurled their weapons into the mass of their enemies. By 1191 the lance was fairly commonly, though not exclusively, couched.

The impact of a charge of armoured cavalry was a tremendous thing, and many enemy forces broke before contact. This allowed the men-at-arms to ride down their foes with relative impunity, protected from random blows by their armour. Even if the enemy stood and fought, few could withstand the onslaught of the heavily armoured Western knights.

This was one of the problems the Crusaders faced in the Holy Land. There they met a foe who knew how dangerous the knightly charge could be, and was quite prepared to fall back or even run away from it. The result was that many times Crusader knights hurled themselves at the foe and hit only empty air. As their horses tired and their numbers were whittled down by the fire of horse archers, the men-at-arms would become exhausted and often found themselves dangerously far from their supporting forces.

The Crusader armies of the time included considerable numbers of foot soldiers and crossbowmen. Most foot soldiers were spearmen with armour of leather or quilted cloth and often a light `helmet’ (i. e. a lesser helm) of leather reinforced with metal bands. Their large shields were their main protection. The crossbowmen were provided with quilted jerkins that offered protection against the relatively weak bows of the Saracen horse archers. Their powerful weapons were slow-firing hut outranged the Saracen bows.

Saladin’s forces at Arsuf were completely different to those of the Crusaders. The backbone of the force was mounted: a mix of light cavalry equipped with short bows and heavier horsemen able to produce a shock effect with their charge, though not so effectively as the European heavy cavalry. The horse archers of Saladin’s force were mainly of Turkish origin. They could attack at close quarters with their light, curved scimitars but these were ineffective against all but the lightest armour. The horse archers were mainly assigned to harass and skirmish with the enemy, though they would swoop down on isolated or broken enemy units to massacre them. The heavy cavalry were mainly of Arab origin. They were equipped with light mail armour and armed with lances, swords and maces. Usually known as Mamluks, these heavy Arab cavalry made up Saladin’s personal bodyguard and more of the army besides. Their function was to deliver the fatal blow to an enemy force shaken by endless horse archery. To back up the cavalry, Saladin had pike- and javelin-armed Arab or Sudanese foot soldiers and Nubian archers. Ideally the pikemen could protect the archers from an enemy attack while they shot down their opponents, then complete the victory by charging with their pikes. In practice this was hard to coordinate, hut the Muslim armies tended to have good discipline and training, and managed combined-arms cooperation better than many European forces of the time.

THE CAMPAIGN

Arsuf was part of the Third Crusade (1189-92), an attempt by a coalition of Christian forces to capture the holy city of Jerusalem from its Muslim rulers. The city had been lost to the Muslims under Saladin (Salah ad-Din Yusuf) after the disastrous battle of Hattin in 1187. Pope Gregory VIII ordered an immediate Crusade to recapture it. The call was answered by Richard I of England (Richard the Lionheart), King Philip II of France (1165-1223) and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (c. 1123-90). The 70- year-old Emperor Frederick was drowned during the march across Europe and most of his army turned for home, leaving Richard and Philip to continue.

Capturing Cyprus as a forward base, the Crusaders landed at Acre and besieged the port, capturing it soon after. King Philip returned home at this point but Richard, now in control of a port through which to supply his army, decided to press on to Jerusalem. With him went much of King Philip’s force.

Richard’s next objective was the port of Jaffa. Marching down the coast, he imposed strict discipline on his force. The army stayed close to the shore to protect its flank and to benefit from the slightly cooler conditions there. The force was arrayed in three columns plus a rearguard. The knights, suffering terribly from the heat, rode in the column closest to the sea. The two outer columns were of infantry. They suffered from the archery of enemy light cavalry who could ride up, shoot, and escape quickly, but the infantry maintained their discipline and stayed in formation, some men marching with several arrows sticking out of their quilted jerkins. The crossbowmen exacted a steady toll among the horse archers, who could not venture too close to the columns.

Marching under fire in this manner is one of the most difficult of all manoeuvres to carry out. Progress is slow and painstaking, since if the formation breaks up at all the enemy will sweep in and attack. Iron discipline is the key, since the galling fire of the enemy makes individuals want to hurry and opens gaps in the formation for the enemy to exploit. It was particularly impressive that the Crusader army maintained its formation, since discipline in the European armies of the time was very poor. Not only did the knights’ warrior instincts tell them to rush out at the enemy but their very way of life had conditioned them to charge at threats regardless rather than plod along hiding behind a screen of common infantry.

For the infantry themselves, the feat is quite remarkable. Often despised by the flower of chivalry they now sheltered, the infantry were forced to bear the brunt of the enemy’s fire for hour after baking hour, and all to protect the precious horses of the knights. They, the infantry, were soaking up arrows to protect animals!

There were plenty of reasons for the formation to fall apart – internal divisions, pressure from the enemy, heat and exhaustion should by all the odds have combined to wear down the Christians’ resolve. And yet the Crusaders’ discipline held. The formation plodded slowly onward, where possible transferring wounded to the ships that followed it down the coast and receiving supplies in return.

On 6 September the Crusader army passed through a wood north of Arsuf, a town north of Jaffa. Had the Saracens fired the wood, it might have become a death-trap, but they did not, perhaps because Saladin had other plans. Thus far the main Saracen force had shadowed Richard’s army but made no serious attempt to engage. Now the time was ripe.

DISPOSITIONS

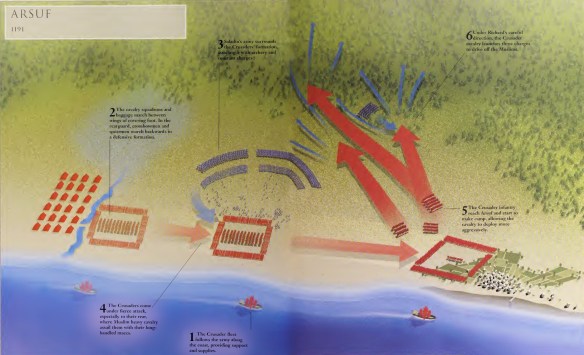

On 7 September the Crusaders had to cover about 10km (6.2 miles) to reach Arsuf, a long day’s march in those conditions. Saladin had no intention of letting them reach the town, however. His forces prepared themselves for an attack that would pin the Crusaders against the sea and crush them.

The Saracen formation was typically fluid, with horse archers darting in to shoot in small groups then withdrawing quickly. There was no idea of forming up for battle, just another day of marching and skirmishing. This went on until about 11.00 a. m., at which point the Saracen force attacked in earnest.

The Crusader army was in effect marching in battle formation, organized in a defensive box around its precious supply wagons and the irreplaceable heavy cavalry. In truth the battle had already been going on for days as the defensive formation held off the horse archers and their supporting forces. There had been no serious attack up until that point but now the Saracens were ready to strike.

The forces of Saladin were kept at bay by a fine piece of combined-arms work. Spearmen protected the crossbowmen from direct attack, while the heavy bolts of the crossbowmen exacted a steady toll on the enemy. And in reserve, the threat of the heavy armoured cavalry prevented the Muslim army from making an all-out assault. For the infantry deployed at the hack of the formation, this was in effect a fighting retreat. Most of the time the infantry marched backwards, keeping their shields and weapons facing the enemy. The Crusader army was a `roving pocket’ cut off in enemy territory yet able to continue its march, albeit slowly. The Muslim forces swirled around the human bulwark; ahead, behind and to the left there was nothing but enemies. On the right flank was the sea. ‘The only hope was to march on – and fight on – so the battle became a contest between the pressure exerted by the Muslims and the discipline of the Crusaders.

STEADY PRESSURE

The pressure steadily mounted as the Saracen horse archers came in ever closer and more boldly to shoot. Sometimes the crossbowmen were able to keep the enemy at a distance, but increasingly groups of cavalry were able to race in and attack with lance and sword. Then the spearmen of the Crusader rearguard were forced to engage. Their spears were long enough to be effective against the attacking horsemen and their shields offered good protection, hut they were desperately tired from day after day of marching.

The rearguard could not afford to become embroiled in a melee with the attackers. If a group of cavalry broke off and was pursued, even for only a few steps, the spearmen would be quickly surrounded and cut down. So the Crusader infantry was forced to fight a defensive battle. Short rushes to drive off attackers were possible, hut it was vital for soldiers to quickly regain the safety of the main force. Dangerous gaps opened up but were sealed by troops who were supposed to be resting inside the defensive formation.

Hoping to draw one of the famously impetuous charges of the Crusader knights, Saladin’s forces concentrated mostly on the rear of the column where the Hospitallers and French Royal Guards rode. If the infantry ever lost control of the situation, the knights would have no choice but to engage. ‘They were already itching for a fight; it would not take much more to provoke them into action. Yet somehow, amid the chaos and constant archery, the rearguard held to its task. It is highly unlikely that there was much order to the formation, not with enemy attacks coming in at various points. The scene would he fluid – chaotic even – changing from moment to moment.

Here a band of spearmen is driving a few paces forward, chasing off yet another attack. There a handfull of crossbowmen are exchanging fire with horse archers; others load and shoot as fast as they can, covering the retirement of the spearmen back to the column. gap in the formation is plugged by a handful of infantry just as Muslim cavalry spur at it, hoping to enter the `box’ and cause mayhem. Finally the spearmen regain the main body and struggle to catch their breath. Things are calm for a moment, with only the constant archery taking its toll. But along the line the scene is being repeated as another attack sweeps in …

For the entire morning the rearguard battled on in this manner, holding off attacks at the end of the column while the force as a whole inched forwards. Despite extreme provocation the knights resisted the urge to charge, and the column continued its march towards Arsuf and safety.

As the day wore on, casualties mounted. The whole force was now under fire, and men were falling dead and wounded. Confined within the formation the knights chafed, forced to take casualties and unable to reply in any way. The crossbowmen did their best and the outer column of foot soldiers heat off a series of minor attacks, hut the strain was becoming intolerable.

COUNTER-ATTACK

As the army neared Arsuf, the pressure became too much for Richard’s knights, The Hospitallers, accompanied by three squadrons of about 100 knights each, burst out of the formation in a reckless charge. Their sudden attack drove back the right wing of the Saracen force, which had been trying to draw such an attack but had ceased to expect it. If Richard did not support the impetuous knights, they would soon he cut off and slaughtered. Yet if he did send more forces after them, he might throw away his whole force. Richard was known for his valour, hut he was also a shrewd tactician. His infantry were near to the shelter of the town. Covered by a cavalry charge they could enter and secure the town as a defensive position, protecting the baggage train and giving the army a safe place to retreat to if necessary.

Richard also knew the temperament of his men. They might attack anway if he did not order it, and without direction their force might he spent for nothing.

Ordering the Templars out, supported by Breton and Angevin knights, Richard launched them at Saladin’s left wing. At last given a chance to release their pent-up rage, the knights threw the Saracens back and repulsed a counter-attack by Saladin’s personal guard. Now the baggage and its accompanying infantry were entering Arsuf. Richard placed himself at the head of his remaining cavalry, Norman and English knights, and led them at the enemy.

Reeling from heavy blows on both flanks, the Saracen army was shattered by the third charge. Saladin’s men scrambled hack into the wooded hills above Arsuf leaving behind about 7000 casualties. No less than 32 amirs had been killed, almost all of them in the three great charges that broke the army.

AFTERMATH

The Muslim army returned to the field the following day, resuming its harassing tactics as the Crusaders prepared to push on to their next objective. There was no attempt to launch another full assault, however. Saladin had learned that he could not penetrate the Crusaders’ defensive `box’ formation and concluded that he could not draw the impetuous knights out of it either. Richard the Lionheart did not benefit from his victory at Arsuf Although he performed a great feat of arms and won a tactical success, his army was not able to take Jerusalem, though a grudging truce was agreed between Saladin and the Crusaders, allowing Christian pilgrims access to the city. Against almost any other Crusader commander, Arsuf would have been another great victory for Saladin. Although defeated in battle he held his army together. Its existence prevented an attack on Jerusalem and brought Saladin an honourable, if less than ideal, outcome to the war.

Tactically, and taken in isolation, Arsuf was a victory for the Crusaders. However, if Arsuf is seen as part of a gradual wearing down of the European army to make it incapable of capturing Jerusalem, it may be that Saladin came out the strategic victor.