Heinz Harmel

Accompanying these new formations through the rear area were those who had been so badly battered that they had been pulled out of the line for rest, refit and reorganization. In Holland this included 9 and 10 SS Panzer Divisions of II SS Panzer Corps, commanded with passion by the highly skilled and well-respected 50-year-old Lieutenant-General Wilhelm (‘Willi’) Bittrich. The SS (Schutzstaffel, or protection squad) was originally formed as protection for Hitler in the late 1920s and commanded by Heinrich Himmler, who sought to make it racially exclusive. By the mid 1930s it had an armed wing (the Waffen-SS), which was increasingly seen as an alternative army. Highly motivated, fiercely proud and rigorously trained, the SS boasted four divisions by 1941 which sought to have no rival on the battlefield and were given the toughest missions. I SS Panzer Corps’ official historian has written: ‘The combined effects of brave officers and senior NCOs and brave, dedicated soldiers made for an extremely formidable military machine. Wounds were to be borne with pride and never used as a reason to leave the field of battle; mercy was seen as a sign of weakness and normally neither offered nor expected.’ The 9 and 10 SS Panzer Divisions were created in early 1943, and during the remainder of the year were trained at various locations in France. SS-Rottenführer Gerd Rommel of 10 SS Panzer Division recalls:

Our training was indeed hard… These were the last divisions that were able to make use of relative peace in the West for their training, before the D-Day invasion in June 1944. However, it was very intensive. They all received the most up-to-date and modern equipment but, because they were so well equipped, a great deal was expected of them when they went into action.

The corps saw action on the Eastern Front a year later, suffering such heavy losses that it was forced into reserve after a refit. However, although still desperately needed in Russia, within a week of the invasion of Normandy it was moved to France, where it arrived before the end of June. Here, both divisions were heavily involved in the fighting and, once again, took substantial casualties. Even so, the two divisions remained dangerous antagonists, and during the Allied breakout they held the line, counterattacked and fought stoically in whatever role was required of them. They became such a feared and highly respected opponent that Dwight Eisenhower said of the final phase of the battle of Normandy: ‘while the SS elements as usual fought to annihilation, the ordinary German infantry gave themselves up in ever-increasing numbers’. But such was II SS Panzer Corps’ sacrifice during the summer of 1944 that both of its divisions were beginning to be referred to as ‘Kampfgruppe’ – a battle group which varied in size and consisted of various divisional elements which took the name of its commander. For example, 9 SS Panzer Division had left Russia 18,000 men strong with a fearsome array of tanks, vehicles and heavy weapons, but by late August it consisted of a mere 3,500 men and a handful of vehicles. Nevertheless, it continued to work in close cooperation with 10 SS Panzer Division, and together they took part in operations in the Falaise Pocket to hold open an exit for other units to escape through before managing to break away themselves. In so doing, the two divisions revealed that they remained not only selfless, but highly competent fighting organizations.

Walter Harzer

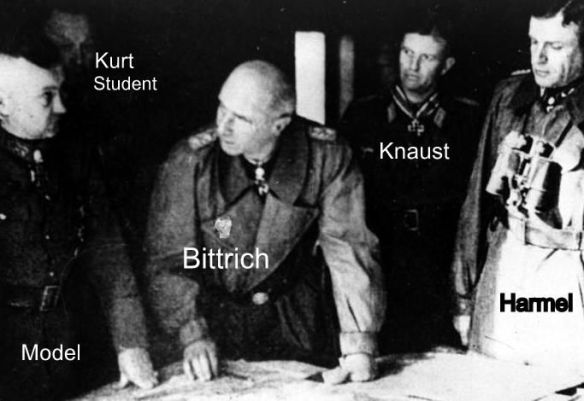

Much of the continued vitality of II SS Panzer Corps came from Bittrich’s excellent direction and the quality of his subordinates. The 9 SS Panzer Division was commanded by the determined and decisive 32-year-old SS-Obersturmbannführer Walter Harzer, who had very recently taken up the position. Looking older than his years and often scruffily presented, he was a first-class combat soldier who had recently been awarded the Cross in Gold for his superb leadership in Normandy. The 10 SS Panzer Division, meanwhile, was commanded by 38-year-old SS-Gruppenführer Heinz Harmel. The debonair Harmel was also a highly decorated officer who had himself been awarded the Cross in Gold and also a Knight’s Cross of Iron with Oak Leaves, a Wound Badge, an Infantry Assault Badge, Tank Destruction Badges and a Close Combat Clasp. He was a popular soldier with his superiors and also his men. SS-Sturmmann Rudy Splinter revealed that Harmel was ‘a real soldier’s soldier, no airs and graces, and he would do anything for his men. It’s no wonder they would follow him anywhere and do anything he asked…’ Thus, in spite of their recent losses, with men of the quality of Harzer and Harmel at the helm, the two formations remained driven and highly competent. Throughout the last week of August, having crossed the Seine, II SS Panzer Corps conducted several important rearguard actions to slow the Allied advance. The divisions stayed just ahead of the British and American spearheads and continued to suffer casualties. Indeed, losses were taken just getting designated replacements to the front from Germany. Nineteen-year-old Alfred Ziegler, a despatch rider for the staff of a newly raised anti-tank unit for 9 SS Panzer Division, remembers that during the train journey to the front, Allied aircraft constantly harassed them:

The first company was caught in a very heavy fighter-bomber attack during which our company commander von Brocke was killed. We all fired our machine guns so that no bombs scored a direct hit on the train. Subsequent strafing runs did, however, cause some damage to the tank destroyers and vehicles, and wounded about 10 men. Later we detrained and joined the third company which had already been in the West for some time. But now the enemy started to chase us.

Ziegler and his unit arrived at the front just in time to fight alongside some German paratroopers. Such actions were always frenetic, with little time for preparation, and exhausting. The division’s armoured engineer battalion was commanded by 41-year-old SS-Captain Hans Moeller who said:

The situation could change by the hour. Every second was vital and called for quick decisions. The engineer battalion was last in the divisional column, and had to look after itself; we had lost radio contact. Should we be struck off as lost already? The weather at this moment was favourable. It had rained and low cloud was hindering enemy air sorties… There was always a feeling of uncertainty. Although not openly admitting it, everyone was preoccupied with the thought that chance or the fortunes of war may yet change. I kept my thoughts to myself, but I knew all these sleeping forms, exhausted, wrapped in blankets and tents, were thinking the same. We were absolutely worn out.

It was the norm for the SS troops to be outnumbered and outgunned. Indeed, when Harzer fought at Cambrai on 2 September he was confronted with ‘200 American tanks and accompanying infantry’. The battle that followed was ferocious and although he later claimed that some 40 of those tanks had been put out of action, by the end of the day his Kampfgruppe had lost most of its 88mm guns, and he had to order his men to withdraw. Its move down the Cambrai–Mons road that night has been described by SS veteran and historian Wilhelm Tieke:

The highway was overcrowded with fleeing vehicles. At the end the stream drove the last prime movers of the 4th SS Flak battery with its sixteen survivors, among them many severely wounded. Shortly before Valenciennes, one of the vehicles broke down. The badly wounded were no longer able to endure the torments of the hasty retreat. The courageous battery medical orderly, Gottschalk, remained with those wounded who could no longer be transported and went into captivity with them.

Having been cut off from the main body of his Kampfgruppe on becoming surrounded, Harzer and his command group only managed to get away by flying British and US flags on their vehicles and taking several unattended Allied trucks that they found at the roadside. The experience was indicative of the division’s role for it fought until the very last moment, and on several occasions they were nearly encircled or overrun. It was by providing such excellent cover for the general withdrawal that Harzer and Harmel stopped more of the German armed forces from being neutralized than eventually occurred. However, such was the intensity of their involvement that the two divisions could not continue in the role indefinitely, and so on 4 September, II SS Panzer Corps received orders to pull out of the line for a rest and refit around the quiet Dutch town of Arnhem, 75 miles behind the front line.

By the time that Bittrich’s corps had been given an opportunity to catch its breath, von Rundstedt and Model were on the cusp of bringing their ugly withdrawal to an end on the line of the Albert Canal. As has been described above, by marshalling units already at the front, and supplementing them with new formations from Germany, a new defensive zone was created that was a credit to German improvisation. This reorganization coincided with the damaging effects of overstretch being felt by the Allies, and so by the time that British Second Army lurched forward again, it found the way barred far more formidably than just a few days earlier. Nevertheless, the problems that Hitler faced after a summer of catastrophic setbacks were chronic, and finding a few thousand new second-rate troops to hold a line together with some shattered comrades was never going to alter his strategic prospects. With every passing day Hitler, OKW and the commanders in the West recognized that a major new Allied offensive was increasingly likely. Between 9 and 14 September Model’s intelligence officer issued daily warnings about increasing reinforcements coming up behind British Second Army and an imminent breakout, probably towards Nijmegen, Arnhem and Wesel, aimed at the Ruhr. This enlightened soldier was further convinced that Eisenhower would deploy his airborne forces, a known and feared commodity which had led to the Germans seeking some depth to their defences, in order to crack the front wide open. In an attempt to read Allied intentions more clearly and empathize with their ambitions, he went as far as to write a report as though he were Dwight Eisenhower giving orders to Miles Dempsey. His instructions to British Second Army were:

on its right wing it will concentrate an attack force, mainly composed of armoured units, and after forcing a Maas crossing, will launch operations to break through to the Rhenish–Westphalian industrial area [Ruhr] with the main effort via Roermond [24 miles east of Neerpelt]. To cover the northern flank, the left wing of the [Second British] Army will close to the Waal at Nijmegen, and thus create the basic conditions necessary to cut off the German forces committed in the Dutch coastal areas [the Fifteenth Army].

Allied plans were somewhat different, for although Model’s intelligence officer had correctly identified the Ruhr as a medium-term Allied objective, the main effort was to seize a Rhine crossing via Eindhoven and Nijmegen. It was this blow – Operation Market Garden – that was about to fall in depth on defences that had not been there just two weeks before. In such circumstances the role of the airborne forces in the undertaking looked not only more important but also far more risky.