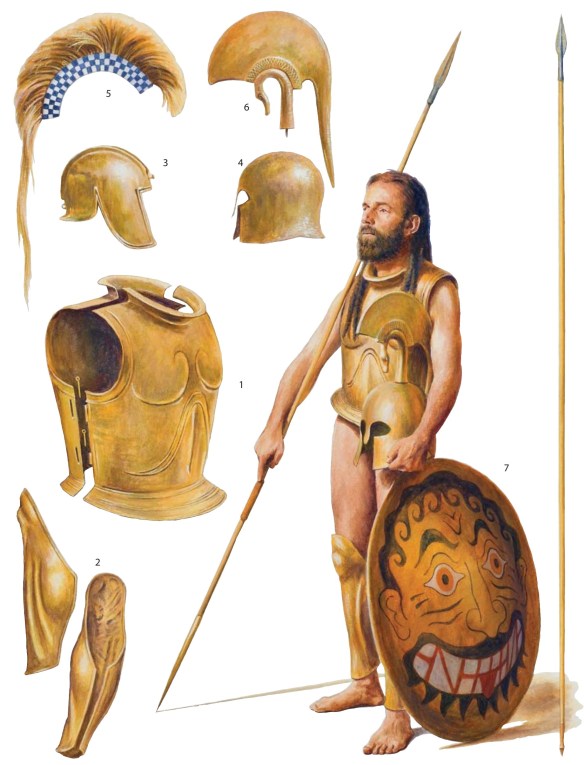

SPARTAN WARRIOR, c. 546 BC This Spartan warrior from the time of the `Battle of the Champions’ is shown wearing the equipment depicted on an archaic Lakonian figurine from Kosmas, in the vicinity of Thyrea (now in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens). Similar archaic figurines, along with the evidence of several vase paintings, confirm that warriors went into battle naked, except for the helmet, `bell’ cuirass (1) and greaves (2). They are often depicted with high crests on their helmets.

The two styles of helmet shown here are the open-faced `Illyrian’ (3) and an early variety of `Corinthian’ (4), which introduced the nose guard and covered more of the wearer’s face. Both styles could be fitted with crests, either made from horsehair (5) or fashioned from bronze (6). The Spartan warrior was a spearman, first and foremost, and is shown with the large hoplite shield

(aspis) and spear (dory). The spearheads and butt-spikes are based on examples in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. The shield emblem is the Gorgoneion (or Medusa mask) (7), a motif that was popular at Sparta, where it recurs on bronzework and on bone and ivory carvings.

This unusual encounter is often called the Battle of the Champions. The Spartans were engaged in a quarrel with Argos over Thyreatis, the territory of Thyrea, which was about halfway between the rival cities. At that time it belonged to Argos but had been occupied by the Spartans. The Argives marched to recover their stolen land. When the two forces met, it was agreed in conference that 300 picked men from either side should fight it out. The battle was bloody, fierce, and inhuman. The killing was on a vile level, and each side knew that no one was to survive. If anyone was to become injured and fall, their fate was sealed because no one was to be rescued from the onslaught. The battle was so intense and fierce that it was at a stalemate all the way down to the last soldier. Left standing were two Argives who had slew the last Spartan warrior. After looking over the area and making sure that they were the last ones alive, they left and returned to their home in Argos, where they informed the state of their victory. However, they had made a mistake and overlooked a Spartan warrior, Othryades, who had survived. He was very injured but was able to make it to his feet. He was able to inform some watchers of his victory, but according to legend, he was humiliated for falling on the battlefield. Guilty, he is assumed to have taken his life due to embarrassment. There is speculation that he died from his wounds, but the Spartan Empire want to make sure their image stayed high in the eyes of the world.

The following day both parties claimed the victory: the Argives because they had the greatest number of survivors, the Spartans because their hero was the only survivor remaining on the battlefield. This argument led to blows and then to a full-scale battle between the two armies. After heavy losses on both sides the Spartans emerged victorious. The Spartan victory, which was thereafter celebrated in the Gymnopaidiai by the carrying of the wreaths known as `Thyreatic’. Moreover, they now controlled Thyreatis and indeed incorporated it within Lakedaimon. Hysiai had been avenged.

The lone survivor of the quasi legendary Battle of the Champions went home and hanged himself, thereby avoiding questions about how he was able to survive such a holocaust.

Survey data indicate that the area of the Thyreatis and Cynuria was already coming under Spartan control in the early sixth century, a process finalized at the Battle of the Champions, corroborating Herodotus’ statement that Spartans “held” the Thyreatis for some time before the battle. It is tempting to associate this Spartan victory with the extraordinary spike in settlement activity in the north and central Parnon region beginning around the middle of the sixth century. The internal colonization of this area resulted in the creation of no fewer than eighty-seven settlements in the area of the Laconia Survey, including one new town, Sellasia. Such a burst of activity could be expected in the aftermath of the failed conquest of Tegea, which prevented settlers from moving north, if Spartan success at the Battle of the Champions had removed the Argive threat to eastern Laconia. Herodotus’ claims that Argos had previously controlled all of the Parnon range down to and including Cape Malea and the island of Cythera may be a trifle extreme, but the Argives’ ability to harass settlers may partly explain why this area of Laconia remained more or less empty until the mid-sixth century.

Male hair is potently symbolic stuff. Spartans signalled their virility and belligerence by growing theirs and went into battle with it all braided and be-wreathed with flowers. In this way, no less than a uniform and no less of a distinctly Spartan trait was the long hair grown specifically for its military function. As to the origins of this Spartan custom we can turn to Herodotos, who reckons the legislation enjoining the Spartiates to grow their hair proudly and terrifyingly long, contrary to previous practice, had first been instituted after the victory over the Argives at the Battle of the Champions. The reality of the Battle of the Champions has been doubted by some scholars, and that is understandable, but it seems that at least in the fifth century BC it was taken as historical. Still, whether or not we chose to believe in the historical truth of this battle is irrelevant here. The point of Herodotos’ story is that the Spartans, at some point in their history, adopted the idea of wearing the hair long as a symbol of militaristic pride, and this is certainly the view later promoted by Xenophon. According to Aristotle, on the other hand, the Spartans thought long hair noble because it was the mark of a free man, since it was difficult to perform servile tasks with long hair.