Most pressing of the Sandys recommendations was the supplementing of the V-Bomber Force with long-range ballistic missiles with the British-designed and -developed (and then cancelled) Blue Streak at the centre but with the loan of US-made types in the meantime, between 1959 and 1963. The US-designed Thor intermediate-range ballistic missile was deployed on Britain’s south and east coasts and the acquisition played an important part in the post-Suez rapprochement between Britain and the United States after the political disaster which was the Suez operation in November 1956. Despite the operational and tactical successes of the air and airborne operations against Egypt, the overall strategic result was a disgrace and caused the downfall of a British prime minister. Anglo-American relations were at their lowest ebb, so buying more American equipment seemed to be a way forward. The manned nuclear bomber remained at the centre of Britain’s strategic response until 30 June 1969 when the first ballistic missile submarine went to sea with the Polaris system. In the event, submarine-launched ballistic missiles turned out to be the more dependable, secure, and cost-effective, leading to the RAF’s loss of the strategic deterrent role to the Royal Navy.

As part of its service time as the prime nuclear deterrent, the Vulcan and Victor were to carry the British-designed 120-mile Blue Steel hyper-velocity stand-off nuclear weapon with a presumed accuracy of one hundred metres. That limited stand-off range did not appear to matter as the Vulcan and Victor were assumed to be invulnerable at 60,000 feet until CIA pilot Gary Powers was shot down by a Soviet SAM-2 at 68,000 feet in a U-2 spy plane over the Soviet Union; he was captured, tried, and had to be exchanged for Soviet spies a few years later. Overnight V-Bombers suddenly seemed vulnerable and the Blue Steel was cancelled in favour of the longer-range American Skybolt missile, two of which could be carried by the Vulcan and for which a 1,000 mile range was claimed. But technology was proving hard for the V-Bomber Force to combat, and when Skybolt was cancelled as too vulnerable the end of the manned nuclear bomber was on the near horizon.

The Vulcan’s distinctive platform shape, with the complex delta design, has distinct ancestry in German designs which were tested in the captured and rebuilt wind tunnels at the Royal Aircraft Establishments at Bedford and Farnborough. Distinct programmes to develop the Olympus power plants and the complex avionics, including the flight control system, were undertaken by British industry, but the cost-plus nature of the Ministry of Supply contracts did not engender good behaviour; contractors added cost at the expense of the taxpayer. In its anti-nuclear flash all over white paint scheme, the Vulcan was as iconic a Cold War strategic bomber to the British as the Boeing B-52 was to the Americans, and, like the B-52, starred in several movies of the time, such as the James Bond film Thunderball in 1965. If there is a criticism of the Vulcan design, it is that the three rear crew members were not provisioned with ejection seats and had to use orthodox parachutes in an emergency, which were luckily few and far between. The lack of interest in the well-being of the non-pilot aircrew was not unusual in the time. Ejection seat maker, Martin-Baker, found a solution for the rear crew but the cost was vetoed by the Treasury without demur by the Air Staff. To both institutions, the ‘two-winged master-race’, as pilots were known because of their double-winged pilot brevets, were considered the only people capable of running the RAF at command level. It would take another forty years for entrenched attitudes to change.

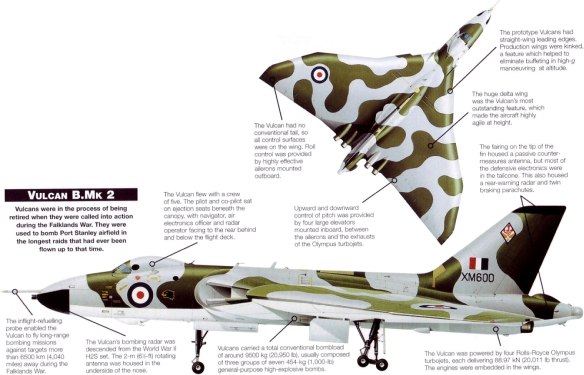

The procurement policy of three competing types was vindicated when the Valiant developed unrepairable cracks in its main wing spars, leading to its early demise. The Victor too had fatigue life issues which were not as severe, so coupled with the need for high-altitude strategic reconnaissance, maritime strategic reconnaissance, additional in-flight refuelling tankers, and low-level tactical engagement kept the Vulcan active until 1984 and the Victor remaining in service until 1993. As a conventional bomber, the Vulcan could carry twenty-one standard free-fall 1,000 lb bombs, giving the RAF a conventional long-range bomber role.

The RAF can claim many firsts in its first one hundred years, and among these the first post-war operational medium jet bomber must be at the forefront. The English Electric company had started work on the design in 1945 and took advantage of the developments at Rolls-Royce to pioneer the Avon axial flow gas turbine engine even without the support of the government. The Canberra proved its worth in a long career which saw it move from bomber to interdiction, electronic warfare to photoreconnaissance platform, and to be the first major Cold War design to be exported to the United States Air Force (USAF). When the PR Mk 9 left service in 1998, it remained the best photographic platform in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance, even though it still used a wet-film camera. For defence, the Canberra relied on its high-altitude performance and agility; as a platform, it was adored by its aircrew.

Sandys also attacked RAF Fighter Command. It would only be responsible for the defence of the bomber bases and the rest by surface-to-air missiles; a glaring hole was the interception of civilian aircraft in the UK Flight Information Region. The government also put an end to the development of a supersonic nuclear bomber and Sandys even wanted to stop work on the English Electric P1, as the Lightning interceptor was termed in 1957. Luckily for both the nation and the RAF, the Sandys Report was allowed to wither away and the research was restarted, although it never reached the level of the early 1950s. Britain’s days as the leading aircraft innovator were over and even the RAF would have to go shopping in America again as it had at the outbreak of the Second World War.

The jet was also proving to be the way forward for RAF Fighter Command with a host of new designs, some good, some excellent, and a few mediocre, but all of which underpinned the British contribution to the new defence framework, NATO, which sprang up in response to the threatening posture of the Soviet Union, its erstwhile allies, and its satellites. It was NATO and the confidence-building measures in post-war Europe that came to dominate RAF thinking over the next four decades, notwithstanding its defence role as Britain stabilized and then withdrew from empire. Britain examined several high-altitude interceptor programmes, clearly understanding that the threat of Soviet bombers delivering stand-off nuclear weapons had to be met at range and altitude. The result was the twin-engined Lightning design where the pilot always seems to have been an afterthought. When it entered service in 1960, it claimed the combat climb record from zero to 60,000 feet in seventy seconds and held it long after it had left RAF service.

Before the Lightning was thrilling the crowds at the annual Farnborough Air Show, Fighter Command was still flying specialist types of day fighter and night fighter, usually based around the same airframe. In the late 1940s, the Gloster Meteor, the Allies’ only operational jet of the Second World War, was deployed across the world in the day fighter version and an effective night fighter with a long nose-mounted radar, developed by Armstrong Whitworth in 1953. The Air Staff realized that specialist fighters were uneconomic and, after competition with de Havilland, gave Gloster the opportunity to develop an all-weather fighter which could carry the Firestreak air-to-air missile rather than be armed with cannon. The Javelin, based to protect Britain’s industrial and population centres, was designed to counter the perceived existential threat of Soviet high-flying strategic bombers carrying nuclear bombs or stand-off weapons. The Javelin replaced the Meteor and was itself replaced by the Lightning. The basic operational concept of these new nuclear-age interceptors was the air-to-air, long-range radar and short-range (dogfight) infra-red homing. Considerable expertise and funding had been lavished on missiles and rockets, making good use of the material captured in Germany by the Farren Mission in 1945. So much faith was placed in the missile and the need to engage Soviet nuclear bombers at ranges where a nuclear detonation was likely to cause little immediate damage that airframe designers were encouraged to concentrate on the carriage of missiles rather than a combination of missile and gun. British designs had names which reflected the age of the comic book space heroes like Dan Dare: Red Top, Firestreak, Fireflash, Skyflash. They took technology to new heights, but they were also costly with little chance of recouping development costs through export sales, so secret was the technology. America’s experience in the Vietnam war brought the gun back into the standard equipment of the fighter just as development of single-role aircraft had started to face the same funding and doctrinal issues as manned bombers. The fighters and bombers of the future would, the Air Staff decided, be one and the same airframe.

With bases across the globe, the RAF, naturally, had the worldwide communications role for the British government. Finding the balance between defending the home base and keeping the supply route open to the Crown Colony of Hong Kong and the dependencies in Africa was difficult and dominated basing strategy; the potential to resupply the South Atlantic possessions didn’t really figure until March 1982, and then, a few days later, at a rush, a new operational approach needed to be made.

Needing to resupply global air bases and the two other armed forces had dictated procurement policy for the transport fleet. Gone now were the days of using converted bombers as a sop to transport needs, as they had been found wanting in the Second World War, but now it was taking airliners and converting them for military service. The latest designs, like the de Havilland Comet, the world’s first jet airliner, and the Bristol Britannia turboprop were pressed into service as transporters and troopers. The route to Hong Kong included stops on bases in Cyprus, Libya, Oman, the Indian Ocean island of Gan and British bases in Singapore, taking several days and generating the need for both bases and overflight rights. Until the 1960s, these bases and rights were relatively simple constructs, but as colonies became dominions or even left the Commonwealth the need for higher-flying and longer-range aircraft developed. In parallel with the commercial airlines, development was quick and the RAF benefited from these developments in engines and fuel capacity.

In the nuclear age, this meant creating new policies for the carriage of nuclear weapons with all the consequences of loading, safety, and security. Although cumbersome, the first air-droppable nuclear weapons like WE 177 were relatively benign for carriage but the political fallout from a loss, as the USAF found several times, could be severe. The carriage of nuclear weapons also meant that the Air Staff made a policy recommendation that only officers should sign for nuclear weapons, thus casting out NCO pilots, as aircraft commanders, in one sweep. This increased training costs and resulted in a new recruitment regime which perhaps better reflected the times than those still practised by the Royal Navy and the British Army. The RAF started to get the reputation as the armed service—and public service for that matter—which valued aptitude over educational background and recruited science, technology, engineering, and maths graduates in preference to the arts and social sciences.

In the nuclear age, the development of tactical transports was at first home-grown, like the Armstrong Whitworth Argosy, known as the ‘whistling wheelbarrow’ because of its engine pitch and aerodynamic layout, but eventually the Americans would supply the ubiquitous Hercules four-engined transport which has served for half of the RAF’s time in being. Even the Argosy was not big enough, and the Air Ministry turned to Short Brothers in Belfast, makers of the giant Sunderland flying boat and the Stirling bomber of the Second World War for a transport. The result was a small number of aptly named Belfast freighters which needed to be based at airfields with the right runway length and infrastructure. As the heavy bombers of US Strategic Air Command had moved out of RAF Fairford in Gloucestershire in 1964, it was immediately taken over for No 53 Squadron’s dozen Belfast freighters on 1 November 1965. As part of the Labour government’s defence cuts, all freight and heavy transport units, now called RAF Air Support Command, were to be based at RAF Brize Norton, a dozen miles away to the west, so this is where the ‘heavies’ went. The tactical transports would be based at RAF Lyneham to the south, just west of Swindon.

Later the Belfast would be joined by the Vickers VC10, new airframes and second-hand airliners, and redundant Lockheed TriStar airliners. They had been acquired and modified for military trooping and in-flight refuelling by British industry, notably Marshall of Cambridge, a company with a longer pedigree than the RAF itself. The VC10 held the distinction of being the fastest large airliner after the demise of the Concorde supersonic transport and would be invaluable for strike aircraft deployment in the coming decades. It could climb to height and refuel a completely new generation of Royal Navy, RAF, and frequently US Marine Corps and Navy strike aircraft. In-flight refuelling would become one of the capabilities which the Americans were particularly keen to have on operations. Using technology recreated by Cobham’s Flight Refuelling Ltd and working out procedures with the Royal Navy and the RAF, Britain led the world in the probe and drogue system and still does. In-flight refuelling extended the range of the nuclear bomber option and strategic reconnaissance, giving the RAF a global presence in the early Cold War; only the USAF could claim a similar capability. Prime Minister Tony Blair was later to insist on a VC10 being configured with beds and armchairs in the presidential role, much to the amusement of the RAF seniors who had seen the royal family relinquish the Royal Flight (No 32 (The Royal) Squadron) transports for the more immediate needs of the government and the military.

The nuclear age saw many changes in the whole physical being of the RAF. By 1952 there were over 270,000 men and women in the service, with National Service accounting for a third. The Sandys Report had a major impact on defence, including the need to redress the balance of military and civilian infrastructure needs at home. Sandys acknowledged that the Attlee government’s plans for rebuilding the armed forces were fiscally impossible and noted that it was this lack of resource which led to the three-month delay in responding to the seizure of the Suez Canal and the debacle for Britain which followed. It was important to restart the relationship with the United States in terms of strategic presence and partnership. The first victim of the Sandys Review had been RAF Fighter Command and the Royal Auxiliary Air Force fighter squadrons, but overall the RAF started to contract so that by 1962 there were only 148,000 in the light blue uniform. The heady days of the V-Bomber Force and taking sole charge of the nation’s nuclear deterrence had gone, and the withdrawal from empire would mean that the overseas commands could be shrunk. With the Ministry of Defence (MoD) taking over the three service ministerial functions and those of procurement, the RAF reduced again in 1968 to 120,000. The reduction in size and changing needs saw the demise of RAF Fighter Command and RAF Bomber Command on 30 April 1968, becoming groups within the new RAF Strike Command, based at the wartime bomber headquarters at High Wycombe. Flying and Technical Commands merged to create Training Command, which itself would be subsumed into Strike by 1977. The front-line operational commands were joined by Coastal Command and Transport Command, in its new guise of Air Support Command, by 1 September 1972, making the RAF into a single operational command entity. After a decade of political mismanagement and with Britain’s standing in the financial world diminished, a second major defence review in 1976 chopped into the manpower and squadron numbers again, leaving just 90,000 personnel. For a while the former headquarters of RAF Fighter Command at RAF Bentley Priory was retained; it had been the headquarters of Air Chief Marshal Dowding in the Battle of Britain. It would go into the twenty-first century too.

Increasingly, contractors were brought in to manage non-operational tasks as the Treasury continued to look for savings through combining functions; not all schemes worked, but some did. On 1 September 1973, Maintenance Command and No 90 (Signals) Group combined to form RAF Support Command which was joined by Training Command on 13 June 1977. RAF Support Command lasted until 1994 when it was split between Personnel and Training Command and a new Logistic Command. The latter became part of the Defence Equipment and Support (organization), and the former was merged with RAF Strike Command to become RAF Air Command on 1 April 2007. Management consultants and name-card printers were no doubt kept busy as the changes were announced.

Another area of change and contention in the immediate post-war period was the employment of women within the RAF. The cultural and social norms of the time made the case for progressing an equal opportunity culture within the armed forces exceedingly difficult and the MoD was even exempted from the terms of the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, even though the WRAF had been administratively integrated with the RAF in 1949; however, flying, the main occupation of the RAF and the position of greatest status, was not available. Slowly, the culture changed. First came the introduction of female undergraduates to flying with the University Air Squadrons and, following the Royal Navy’s lead in allowing women to go to sea in warships in 1990, there was nothing to stop the Air Force Board from re-examining flying places for women. True, there had been volunteer female NCOs in transport aircraft and helicopters as air quartermasters since 1961, and slowly the concept that expertise was more important than gender won over the sceptics. It was a hard fight and several battles were lost with ‘crusty, old Air Marshals’. In 1989, the first female operatives were trained on the E-3D Sentry airborne early warning and control aircraft; one of the issues was the prevailing doctrine that all student pilots in the RAF were seen first and foremost as fast jet pilots and the aerospace medical concerns, misguided though they may have been, were taken to rule out female fighter pilots. Helicopter and transport aircrew were cast in a secondary light as failed fast jet aircrew, a dogma that persisted until the end of the twentieth century. Having got through the discrimination on marriage and then pregnancy, the problems of late Cold War recruitment and the rapidly changing society norms of the 1980s were making the RAF look sexist, and on the back foot; that’s not a place that the RAF liked to be. Slowly, helicopters and transport aircraft aircrew places were opened to women, with a few caveats about combat areas, in April 1990. The final steps were removing the view that women would adversely affect military effectiveness and some form of concern about health and welfare, including the notion of fast jet women ‘having displaced wombs’; the latter was quickly dispelled by the experience of the US Navy. In December 1991, the opaque flying training ceiling was broken and it was announced that women were now eligible for combat jets; the RAF has never looked back. Since 1991, there have been female Air Vice-Marshals, Tornado bomber squadron commanders with operational experience over Iraq and Syria, and Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) pilots with the Typhoon Force. Even the toughest unit, the RAF Regiment, which was formed in the Second World War to protect airfields and air units around the world, opened its doors to women applicants from September 2017. The RAF enters its second century as an equal opportunity employer with the focus firmly on people, and the challenges of attracting the right people at the right time to the right jobs, competing in the jobs market with civilian high-tech companies. Sir Michael Fallon MP, the then Secretary of State for Defence, said in 2017 that the future RAF needed ‘people as attuned to apps as aeroplanes, switched on cyber warriors who don’t fit the traditional mould’.