It was clear to the British government that it needed a nuclear capability, and the quickest way to achieve this policy goal was via the RAF. Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin summed it up in 1946 after a trip to Washington, DC:

We’ve got to have this thing. I don’t mind it for myself, but I don’t want any other Foreign Secretary of this country to be talked at or to by the Secretary of State of the United States as I have just been in my discussion with Mr Byrnes. We’ve got to have this thing over here, whatever it costs…We’ve got to have the bloody Union Jack flying on top of it.

The United Kingdom was the third nation to enter the nuclear age when it tested an independently developed weapon in October 1952, and in true British style there was a new policy to support the US ‘atomic supremacy’ over the Soviet Union. By 1951, the United Kingdom was spending 10 per cent of its gross domestic product on defence, building up both conventional and nuclear forces based on the Defence Policy and Global Strategy Papers issued jointly by the Admiralty, War Office, and Air Ministry in 1950, before the outbreak of the Korean War, and in 1952, because of the Korean War. These papers implied that a hot war, rather than a cold war, was most likely and that it would be fought in Europe and need land and air forces with a strategic last resort of atomic weapons delivered by strategic bombers. This was the beginning of the age of the V-Bomber.

Although no aircraft were directly involved in Operation Hurricane, as the first atomic test was code-named, in it and the seven subsequent tests the RAF took the lead in understanding the technological needs and how to harness the technology for military effects. It looked at strategic and tactical delivery, working out the equipment, basing, and governance for the whole nuclear construct. There were then nine successful hydrogen bomb tests in 1955–62 in the central Pacific, giving the British a more advanced capability than simply negotiating for American weapons. For the RAF, the advent of the nuclear age meant global presence, an enhanced relationship with the Americans, and a ticket to demanding funding for long-range capabilities from the Treasury.

The British Blue Danube (Smallboy) nuclear bomb.

Britain’s first nuclear weapon was code-named Blue Danube and the first example was delivered to the Bomber Command Armament School at RAF Wittering on 7 November 1953, to be followed by the radioactive core about a week later. The weapon was available a full year before the carriage aircraft, the Vickers Valiant, came into service; probably a ‘first’ in the history of British air power procurement. It was not until 11 October 1956, in Australia, that the first drop was made, but the system was clearly still in the early stages of development. Nevertheless, the Air Ministry was keen to demonstrate a nuclear deterrence capability and ‘sustaining a nuclear capability requires a wide range of capacities built over a protracted period’, noted one senior official—in fact, it would take nine years to be declared fully operational. The building of the Blue Danube and later Red Beard weapons owes more to craft work than mass production; an interesting parallel with the more usual symbol of the RAF, the Supermarine Spitfire, which also suffered from production issues in 1937–8 because of the same craft-building rather than production-line experience of Supermarine at Southampton.

Nuclear weapons would take the RAF and Bomber Command into a new era. Gone would be the Main Force stream, bombing on markers put down by the Pathfinder Force and the possibility of using alternative targets. There was one target for each nuclear weapon with bombing by reflected radar image and everyone knew it would be a war of frighteningly short duration with little chance of a safe return home for the aircraft and aircrew. It was a highly secret world of euphemisms, passwords, special codes, and sudden drills and scrambles. No V-Bomber ever flew with a live nuclear bomb but the capability was very real.

Nuclear weapons are only as potent as the means of their delivery. Britain had been developing its heavy bomber force into a strategic asset since 1943, although strategic bombing as a doctrine had been extant since the very creation of the RAF. Work on building a high-altitude strategic bomber to fly faster, higher, and further than the Avro Lancaster had been advanced by the engineering genius Barnes Wallis, leading a team at the Vickers-Armstrong company at Weybridge, and resulted in the Windsor pressurized bomber. Dambuster Squadron Leader Joe McCarthy, the American Canadian expert on Lancaster operations with three full tours in the wartime Bomber Command, had been seconded to advise on the Windsor and found it an improvement on the Lancaster but not greatly so, except that the pressurized hull took crew comfort into a new dimension.

The Windsor might have been a step up on the Lancaster, and even handled better than any previous large aircraft, according to the legendary test pilot and head of the Aerodynamics Flight at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough, Lieutenant-Commander Eric (Winkle) Brown, but like the Spiteful with which Vickers wanted to replace the Spitfire, it had been eclipsed by the march of technology. The piston engine was on its way out and the jet engine (including the turboprop, which was like a piston engine but was jet-powered) was on the way in. Yet there was still a need to deliver an atomic weapon across the Iron Curtain, and as the follow-on to the Lancaster, the Lincoln (designed for the Pacific War), did not have the range, the Air Ministry convinced the always reluctant Treasury to shell out scarce dollars and acquire eighty-eight Boeing Washington long-range bombers—a simple systems modification to the B-29 strategic bomber which the Americans had been using to degrade Japan’s will to fight a few years before. The Washington also had the nuclear weapon delivery fittings for weapons with which the RAF was not equipped; it only remained in service for three years, coincident with the Korean War (1950–3). It would take another decade for a British system to be developed and for the rebuilding of selected air bases in Norfolk and Lincolnshire. At the same time as acquiring the Washington, the Ministry of Supply took delivery of four squadrons’ worth of Lockheed Neptune maritime patrol aircraft, which operated alongside maritime conversions of the Lancaster.

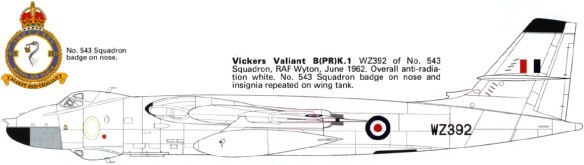

Having seen the potential of the jet-powered Arado Ar 234B-2 bomber developed in Germany at the end for the Second World War, the details of which were brought back by the Farren Mission in July 1945, the Air Ministry was keen to use the technology to increase range and reduce operating costs. Kerosene, from which Jet A-1 fuel is made, is kilogram for kilogram the most effective power source, and the chemical engineering to create kerosene is so simple that it could be available in abundance. The jet engine was clearly the only way to go with the strategic bomber force, but what was to happen in the meantime? The Attlee government, keen to cut the armed forces to the bone, would not fund the Windsor nor did the Air Ministry want to keep the Washington in service any longer than necessary when jet bombers were just around the development corner. The US Congress was concerned about exporting nuclear technology, and although Britain had resourced and added considerable knowledge to the Manhattan project which created the first atomic bomb, US technology was suddenly restricted, and the Labour government of the time had no bargaining chips left with which to entice President Truman. Thus, it was realized that Britain must start its own programme. The three leading aerospace companies, Avro, Handley Page, and Vickers, were contracted to design bombers to specification B35/46 in a plan which proved highly advantageous when it came to redundancy of design, giving the RAF the option of the Vulcan, Victor, and Valiant for the strategic role. Known, for obvious reasons, as the V-Bomber Force, the RAF inventory in June 1964 was fifty Valiant, seventy Vulcan, and thirty-nine Victor bombers in front-line service. The first V-Bomber Force base—the V for the first letter of three types—was RAF Gaydon, south-east of Leamington Spa in Warwickshire, selected for the Operational Conversion Unit because of a series of Fighter Command airfields to the east between it and the potential strike capability of the Warsaw Pact. Its wartime runways and hardstandings were improved and new hangars were built for the Valiant, opening on 1 March 1954. Valiant and later Victor aircraft were based here until 1965, by which time twenty-seven hardstandings had been built and three runways completed. To cope with these heavy and rapidly responding bombers, considerable investment was made in the infrastructure of the home and deployed bases. Too big for hardened aircraft shelters of a later decade, the V-Bomber Force would have long runways, strengthened taxiways, and newly conceived dispersals in an H-pattern which was deemed to give the fastest egress to the active runway. More housing was built and more accommodation for a new generation of volunteer airmen who were needed to service the bombers and operate the support equipment. The 1950s saw the end of National Service conscription and the beginning of a recruiting campaign which saw technology as the draw for young men (the RAF was not yet the equal opportunity employer it became three decades later). New skills in aircrew trades such as electronic counter-measures and navigation systems, as well as heavily guarded bomb dumps, needed investment on a scale not seen since the 1930s.

No RAF open day at Finningley, Waddington, Wittering, or Scampton, to quote the most-seen examples, was complete without a ‘survivability scramble’ or quick reaction alert which saw Vulcan crews run to their aircraft, start, taxi, and stream take-off within minutes, simulating what would happen in event of the alert. It reminded many who watched of Fighter Command and the Battle of Britain. It was not just for show, for this was the era of the four-minute warning provided by the ‘golf ball’ radomes of the ballistic missile early warning station at RAF Fylingdales high on the Yorkshire Moors, which became operational in 1964 and were linked to the US Strategic Air Command network. These were the days of high confidence in the deterrent of all-out nuclear response to Soviet aggression and the continued availability of four of each squadron’s eight bombers at any one time; the mathematics were that two would be in base-line maintenance and available very quickly and two away for deep maintenance, so that four were front line and six at a push.

Vulcans were capable of rapid deployment to bases around Britain like Cottesmore, Boscombe Down, and St Mawgan, and across the world with plans in place for operations from Akrotiri (Cyprus), Gan (Maldives), and even bases in the Gulf region. A whole range of specialist equipment was designed and procured to support the V-Bomber Force, including Standard cars capable of carrying five members and their luggage and a host of handling kit which could be air transported as needed. The V-Bomber Force became a highly motivated team for which recruitment never seemed to lag; at its peak, there were 174 bombers in seventeen squadrons, including the conversion units, making up the V-Bomber Force.

The Vulcan and the Victor had a global presence through their range, endurance, and a certain 1960s feeling of inspired technological advance. When the first Vulcan was delivered to RAF Bomber Command in September 1956, it was immediately sent on a global tour to New Zealand; sadly, the toured ended in tragedy when the bomber crashed at London Heathrow Airport on its return in bad weather. A bad decision by a very senior officer wanting to bask in the highly public arrival led to the death of the three rear crew; there were diversion airfields available but out of the public limelight. Nevertheless, the Vulcan achieved almost unprecedented professional and public affection because if its shape and capability; it became, in truth, a national icon. Yet it nearly foundered early.

The damning and damned Sandys Report of 1957, which insisted that missiles would replace the manned aeroplane, cast long shadows over the RAF and its future as a global air power player. Named after Duncan Sandys, the newly appointed minister of defence and son-in-law of Sir Winston Churchill, the report cut defence research and development and made a dogmatic emphasis on missiles over men. For several years, it fundamentally rocked the whole spectrum of defence, and although later much of the policy was reversed, it was too late for several companies which went out of business or had to merge with rivals. It created a streamlined but less capable aerospace industry with one dominant airframe company and one dominant engine manufacturer; this turned out to be a false economy which led to bankruptcy and several stillborn aircraft projects.

The underlying reason why the Sandys Report was so unsettling has more to do with the precarious financial situation of the country, still having not recovered from paying for the military equipment procured from America two decades before. Despite the ability and creative power to come up with world-beating technologies, the funding was simply not available to develop the ideas. The replacement for the Canberra and the remaining V-Bomber Force was the TSR-2 which was a decade ahead in capability terms of its nearest rival, the General Dynamics F-111; this was not appreciated in the Pentagon. Part of the terms which the government of Harold Wilson acceded to in return for American support of the pound was the cancellation of the TSR-2 project and the destruction of the production jigs at the Weybridge factory. Britain ordered the F-111 instead but it was found wanting; it was another American strike and reconnaissance aircraft that was ordered, the McDonnell Douglas Phantom.