The Battle of Brunkeberg not only saved the nascent Swedish nation state from being submerged in a Danish-dominated Scandinavian Union but saw a modern, professional army defeated and routed by a committed and well-organized peasant militia.

In 1397 the three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden – with the Grand Duchy of Finland – created a union, with Queen Margaret of Denmark (1353-1412) as head of state. Due to the mutual suspicion and antagonism of the Danes and Swedes the union functioned poorly and when Margaret died in 1412 the Swedes broke away. They chose their own ruler, Charles VIII (Karl) Knutsson Bonde (1408-70), as their king, but when in May 1470 he died after a series of disjointed reigns. King Christian I of Denmark (1426-81), the legitimate ruler of Sweden, saw his chance to wrest back his throne.

In Stockholm, however. King Charles VIII’s nephew, Sten Gustavsson Sture (1440-1503), was elected by the Swedish grandees as Riksfdrestdndare (Lord Protector or Regent); he was supported by the old king’s followers and his relatives, such as Nils Sture (1426-94). But Christian I was determined to assert his legitimate claim and during the early summer of 1471 set about mobilizing his army. He secured shipping to transport his force to Stockholm by making a deal with the Hanseatic League, which was granted a monopoly on trade with Sweden once it had been forced back into the union with Denmark.

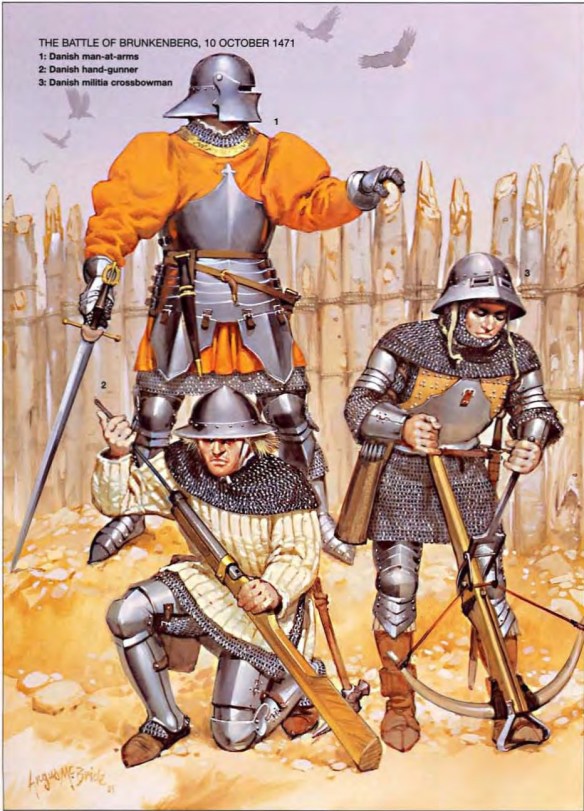

The two armies were fundamentally different. Both militarily and economically, the Danes were the stronger of the two peoples, coming from a more prosperous, populous and fertile country. The king’s army consisted of 3000 Danish troops that varied from mounted knights to regular infantry and armed peasant levies – the latter contained a small Swedish contingent loyal to their legitimate ruler. In addition there were 2000 or so German infantry – hardened professional mercenaries. The Danish army liked to fight regular battles in the open field where their material preponderance, military experience and superior discipline could he used to best effect. If the Swedes faced the Danes and Germans in the open they would be, or so the Danes believed, cut to pieces and slaughtered wholesale.

By contrast Sten Sture’s Swedish army consisted of lightly armed yet mobile peasants in arms, some tough professionals, and a handful of mounted knights (about 400). The core of the army, nine-tenths of it, would be made up of peasant levies armed with swords, pikes, axes, crossbows and longbows. The favourite tactic among the Swedish peasants – put to good use in the wooded, hilly Swedish countryside – was the ambush, and at Brunkeberg, Sten Sture would use that peasant tactic, but on a far greater scale, to good effect.

THE CAMPAIGN

In late July 1471 the Danish fleet of 76 ships with the army on board set sail from Copenhagen harbour heading east towards Stockholm. To reach the city the Danish fleet would have to navigate through the treacherous, shallow waters of the vast archipelago that blocked the entrance to the Swedish capital. The archipelago consisted of literally hundreds of low-lying islands and underwater rocks sitting just beneath the surface. This made the Stockholm archipelago a navigator’s nightmare but it says something for the Danish admiral’s skills that the entire fleet sailed safely into the harbour of Stockholm without losing a single ship. No doubt a well-paid Swedish pilot had been recruited!

The Danish fleet anchored between the islands of Kapplingeholm and the larger, wooded island of Vargo (Wolf’s Island), just across the water from Stockholm Castle. The city, located on an island, could not be stormed by a conventional army nor assaulted properly by a fleet. Its approaches from the easterly side, facing the Baltic, were protected by a strong wooden palisade that protruded out of the water and blocked off Stockholm from a naval assault. It could only be attacked by an invader on the landward side from either the north or south. Both approaches were blocked by powerful turreted drawbridges and fortified gates. In the north Stockholm Castle gave added protection should the Danes attack.

But Christian had no intention of subjecting this formidable fortress city to a regular siege. He wanted his enemy, Sten Sture, to come to the relief of Stockholm, where the king hoped to defeat the `rebel’ Swedes in a regular battle he was sure his modern and well-equipped army would easily win. The Danes began to land their troops on Kapplingeholm on 18 August and immediately began to build a fortified camp atop the southern end of Brunkeberg. They built earthen ramparts topped by earth filled wicker baskets, wooden palisades and a strong stockade. The Swedes were shocked at the speed of construction and the defences. At regular intervals were openings for cannon – a new form of weaponry that came as a unpleasant surprise to the Swedes. This Brunkeberg camp was pivotal to Danish strategy. Had King Christian kept on the defensive he might have secured a victory by attrition. Sten Sture would have had to relieve Stockholm and this would have forced him to attack if the Danes remained on the defensive.

DISPOSITIONS

Both sides were quietly confident that they would win. The Danes had skill, better weapons and a fortified camp to bolster their chances, the Swedes, however, were fighting on home ground and knew the terrain far better than their enemy. On the high, wooded and boulder-strewn ridge of Brunkeberg, knights in armour, artillery and regular infantry would not be in their element. Swedish chances of winning were heightened by Christian I’s dispositions. In the face of an enemy of unknown strength an army should be kept together and not divided up.

The king, however, split his far smaller army into three parts to defend vital strategic points on the battlefield. Should things go badly wrong for the Danish side then their retreat back to the fleet had to be secured by a detachment of cavalry and some infantry. Furthermore the Stockholm garrison had to be prevented from joining up with the Swedish field army – so Christian placed another detachment to defend the pivotal position around the convent of St Klara. The main part of his army remained in the Brunkeberg camp.

The Swedes and Danes agreed to a truce that was to last until late September in order to make crucial preparations for a battle that could prove decisive. While Sten Sture went south to recruit more peasant troops and provincial knights, his cousin. Nils Sture, went to central Sweden for the same purpose. If Sten Sture wanted to win against King Christian then he had to secure the support of the belligerent anti-Danish population of Darlecarlia and Bergslagen. It took Sten and Nils what remained of the month of August and the whole of September to recruit the vast host of armed peasants that would make up the Swedish army at Brunkeberg. But on 9 October their contingents were finally assembled and united into a single army at Järva, north of Stockholm. In total the Swedes numbered some 10,000 men, or twice the number that Christian had at his disposal. This numerical preponderance would prove crucial and more than make up for the enemy’s higher troop quality.

During the following day Sten Store’s army marched from Järva and took up position, under cover of darkness during the night of 9/10 October, just northwest of St Klara. On the morrow not only his but his entire country’s fate would hang in the balance, but he was sure that his strategy would work. Christian’s plan was to lure the Swedes into fighting in the open, to be annihilated by a modern European-style army. But Sten Sture had no intention of doing what the king wanted. Instead he would use a simple but shrewd plan to trap, overwhelm and defeat the Danes.

While his army attacked the Danes from the front against the slopes leading up to their camp and the St Klara convent. Nils Sture would take his Darlecarlians around the ridge to the north. Once they had crossed it and made their way east they would regroup on Ladugardslandet, where the inhabitants of the capital grazed their cattle. As quickly as possible. Nils would then attack the vulnerable rear of the Danish position from the east and hopefully overcome the Danes through a combination of surprise and sheer numbers.

To make doubly sure that this strategy would work, Sten Sture had ordered Knut Posse, the Commandant of Stockholm, to put his troops and armed Stockholm burghers into boats, row across the narrow canal separating the capital from the mainland and land on the opposite shore. Posse was to attack the Danes holding St Klara in the rear and give Christian a nasty surprise. Now if everything went according to Sten Sture’s plan the Danes would be attacked on three sides giving them two simple options: fight to the death where they stood or flee for their lives towards their anchored fleet. Only the unfolding battle the following day would show if Sten Sture’s clever plan would work.

THE BATTLE BEGINS

By early morning the Swedes were in position. The battle began at 11.00 a. m. and would continue for four gruelling and bloody hours. The Swedes fired volley after volley of arrows at the Danish camp and positions. The Danes, better equipped and with modern weaponry, answered with cannon fire. Sten Sture launched his first attack that was met by the Danes. Seeing his exposed corps around St Klara threatened bv this second Swedish offensive, Christian committed his troops. They left the safety of the camp and counter-attacked in the open to save the St Klara position. Danish self-confidence soared as their flanking attack against the Swedes seemed to take effect. The battlefront was now one long chain of fighting men stretching for almost a kilometre (0.6 miles) through partially open fields and rocky woodland. It was close-quarters lighting, man against man with axes, pikes, swords, spears, cudgels and daggers. The continuing battle had distracted the Danes as Sten Sture’s strategy of encirclement began to take shape. Finally, by the afternoon. Nils Sture’s Darlecarlians were in position to the east while the Stockholm garrison rowed as silently as they could for the opposite shore.

SURPRISE ATTACKS

Nils Sture signalled for his men to advance. ‘The Danish outposts were swiftly and brutally dealt with, then, when they reached the Danish camp the Darlecarlians, the most feared of the Swedes, launched themselves at the poorly defended ramparts facing east with a roar. Meanwhile, led by Posse and Trolle, the Stockholm troops had landed on the shore and regrouped rapidly for an attack towards the convent, where they hoped to surprise and overwhelm the Danish defenders. It worked. The Danes were taken completely by surprise by Posse’s attack. Here the training and superior arms of the king’s troops were of little avail as wave after wave of snarling Swedes poured in on them from all sides.

The Danes were no weaklings and as professional troops fought back with controlled ferocity and great skill. But there were too many of the enemy as the infantry fought a hand-to-hand battle while the mounted Danish knights were unhorsed one by one. As they came crashing down, the knights were bludgeoned or stabbed to death by the peasant soldiers they had held in such contempt at the beginning of the battle. Christian shared his knights’ contempt for the enemy and the usurper rebel Sten Sture, and had thus expected an easy triumph once the Swedes were committed to battle. Instead it was his army that had walked blindly into a trap. Now, as the horrified king saw his men dying and his proud army buckling under the enemy’s onslaught, the question was how much, if any, of his army could be saved?

The Swedes were not having everything their own way, however. Knut Posse – in contrast to Sten Sture – led his men from the front and paid a terrible price for his bravery. Danish crossbowmen hit him in the legs and then a Dane or a German infantryman hit him over the head with an axe. He was carried, dying from his wounds, back to Stockholm. Nevertheless, his demise did not dampen the resolve of the Swedes, who scented victory and redoubled their efforts to destroy the enemy. Christian had committed a series of blunders and he may have had his faults as a commander but cowardice was not one of them. He ordered his personal guard to join him at the very centre of the fighting to drive back the Swedes and rally his faltering men. Perhaps the king was courting death, preferring to meet an honourable end in battle rather than survive a defeat. His bravado ended abruptly as he was hit by a small cannonball, leaving him badly wounded. His place was taken by one of his toughest and bravest commanders. Count Strange Nielsen, who tried to rally the troops carrying the Dannebrog (the white and red Royal Danish flag). He was killed outright.

The Danes and Germans began to waver and break. A handful of fleeing men became a hundred and then the flow of retreating soldiery became a torrent of panic-stricken and terrified humanity with only one thought on their mind: to flee. There was now no pretence of a well ordered retreat – it was a rout and it ended in tragedy as the rickety bridge between the mainland and the island of Kapplingeholm collapsed under the enormous weight of fleeing men and horses. Danish boats, sent out from the fleet, rowed up to shore and picked up survivors. Once those that could be saved had been taken aboard, the fleet sailed back to Copenhagen. King Christian had lost half his men – some 900 had drowned, another 900 had capitulated to the triumphant Swedes at the camp and the rest lay dead on the battlefield.

AFTERMATH

Sten Sture had saved Sweden’s fledgling statehood and independence but it had been a dearly bought victory for the Swedes. For the next 250 years Denmark and Sweden fought a series of bloody wars against each other with all the hatred and ferocity showed at Brunkeberg.