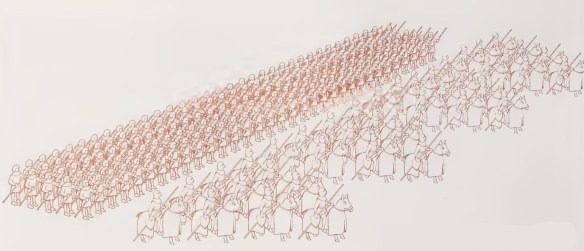

The wedge formation consisted of battle lines ‘made up of a number of deep wedges of cavalry, followed by infantry. The more heavily armed knights would lead the wedge, while the more lightly armed men-at-arms would form the centres. The idea was to slice into the ranks of the enemy and disrupt their formation, after which the infantry could follow up to provide the final blow.

The Milanese carroccio was a ceremonial wagon built to reflect the town’s pride and wealth. Taken with the town’s militia to the Battle of Legnano, it was meant to encourage the more inexperienced soldiers when they faced Frederick Barbarossa’s veteran forces, and did so successfully to judge by the result of the battle.

Frederick Barbarossa’s military career has been celebrated since his death. His career included several marches through the Alps to put down northern Italian rebellions. Most of these were victories. Yet it is perhaps his defeat by the Milanese and other northern Italian militias at the Battle of Legnano that is most remembered.

On one of his numerous campaigns through the alps into northern Italy, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa’s army was defeated by non-professional soldiers drawn mostly from the town militias. The Battle of Legnano was a victory of inexperienced over professional troops.

Throughout history, the Alps have stood as a geographical hindrance to any military force trying to cross over or through them. From Hannibal to Hitler, armies have been tormented by man and nature as they tried to travel through narrow and precipitous passes, making the journey long, gruelling and dangerous. Above all, this mountain range protected Italy. More than any strategy, army or weapon, the Aps saved Italy from numerous conquests. During the Middle Ages, the Italian people were politically and legally part of the Holy Roman Empire, but they almost always sought their own sovereignty, especially after the towns of northern and central Italy increased in population and wealth during the High and Late Middle Ages. This meant that medieval Italians generally opposed being ruled from north of the Aps.

However, the Holy Roman Emperor often had other considerations that kept him from Italy. The difficulty of the Alpine passage, as well as the distance between there and his powerbase in Germany, allowed only an emperor who was completely secure at home to campaign in Italy. Such security was rare in medieval Germany, due to its custom of imperial election, which frequently fomented jealousy among imperial candidates and their adherents. When such security did reign, though, and the emperor came south, the Italian towns were often unwilling to surrender their political independence without a fight. When these wars were fought, the Italians usually were defeated by the more professional, more experienced, more skilled, better-led, and better-armed and better-armoured German troops. But sometimes the Italians were victorious. One of the battles won by the Italians against the Germans was fought at Legnano on 29 May 1176 between the troops of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and the soldiers and militia of Milan and other allied Italian towns.

THE OPPOSING FORCES

Frederick Barbarossa was already an experienced military commander when he was designated the successor to Emperor Conrad III (1138-52) in 1152. In fact, it may well have been the generalship he exhibited when fighting Duke Conrad of Zahringen’s rebellion on behalf of Emperor Conrad that led to his being recognized as his successor, despite having no familial ties to him. This same military leadership no doubt won him a unanimous election, a rarity in medieval German politics.

It had been a while since the Italians had seen a German army south of the Alps. Neither of the two emperors who preceded Frederick, Lothair II and Conrad III, were strong enough to pursue any more than a diplomatic connection with the inhabitants of Italy; in essence, the Italian towns were virtually independent for more than 50 years. Among other things, the Holy Roman Empire had been unable to collect taxes and other duties, while the Alpine passes were so filled with bands of thieves, that few traders, pilgrims, churchmen or other travellers could pass through them safely without paying for protection.

Two years after ascending to the throne, Frederick undertook his first campaign through the Alps, ostensibly to be crowned as emperor by the pope and to clear up the lawlessness of the roads and passes, but also, certainly, to bring Italy back into a political and economic union with the rest of the Holy Roman Empire. The latter aim brought an immediate response from the stronger northern and central Italian towns and their neighbours. But Frederick Barbarossa realized little from this campaign, except for his coronation, necessitating his return again (and again).

That the townspeople of Milan led this first rebellion against Frederick is easy to understand since their wealth derived largely from being in control of many of the passes through the Alps. Any traveller who wished to journey along the shortest paths into Italy had to pass through Milan. This meant that the town was continually filled with pilgrims and traders, who spent large amounts on housing, transportation, guides, protection and victuals from the townspeople. As so often in medieval Europe, wealth translated into a longing for independence. Of course, this meant that the Milanese frequently opposed any control from the Holy Roman Empire or its lords. Perhaps also due their wealth, they were able to inspire the citizens of neighbouring towns to join their rebellions against the empire, even if neutrality might have served them better.

THE CAMPAIGN

When Frederick Barbarossa returned to Germany in 1155 without securing Italy’s subjugation, his barons saw this as weakness, and the recently crowned Holy Roman Emperor had to quell dissent among them. Eventually, Frederick was able to placate or defeat all of his adversaries, through diplomacy as well as military power. His second campaign to Italy took place in 1158, and this one turned out to be quite a bit more successful than his first. His greatest victory was without a doubt the capture of Milan, which fell on 7 September 1158 to Frederick’s forces after a short siege. Other rebellious Italian towns quickly surrendered.

But there was still no peace south of the Alps. Once Frederick returned to Germany, Milan and most of the rest of Italy again declared their independence, forcing the emperor’s third expedition south of the Alp; in 1163. On this occasion, his army faced a new alliance of earlier enemies, the Lombard League. The Lombard League had been formed initially by the smaller towns of Verona, Vicenza and Padua, hut soon more substantial allies joined in: Venice, Byzantine Constantinople and the Kingdom of Sicily. In the beginning, Milan stayed out of the league, although probably more out of fatigue than disagreement with its purpose. Facing the unity and military strength of the Lombard League, Frederick’s 1163 campaign failed, as did another campaign, his fourth, in 1166. In this latter expedition, it was not only the Italians who defeated the invading Germans, but also disease, in particular fever, which almost annihilated them. Seeing their success, the Milanese joined the league.

Frederick Barbarossa did not campaign in Italy again until 1174, when he went there to prevent an alliance between the Lombard League and Pope Alexander III. Since being made pope in 1159, Alexander had remained neutral in more northerly Italian affairs, although never a friend or supporter of Frederick. Now he had begun to entertain the Lombard League’s petitions for alliance, and with it, obviously, papal approval for their rebellion. Such an arrangement was not in Frederick’s interest, and he was determined to stop it. When he was unable to do so diplomatically, he launched a new campaign. It was during this campaign, in 1176, that Frederick fought and lost the Battle of Legnano.

DISPOSITIONS

The original sources for the Battle of Legnano do not provide adequate detail for all of the action on the battlefield. Surprisingly, despite its importance to his military career, the chroniclers and biographers of Frederick Barbarossa, generally quite descriptive about all facets of his life, are silent on the battle, while the few local Italian histories are quite short.

From 1174 to 1176 Frederick travelled around Italy, trying to bring the Lombard League to battle. By 1176 he had become frustrated at the lack of progress he had made: the Italians had not been pacified, nor had the pope backed down in his support of them. Early in the year, the emperor had called for reinforcements from Germany, and in April, 2000 additional troops arrived from Swabia and the Rhineland. This force was led by Philip, the Archbishop of Cologne, Conrad, the Bishop-elector of Worms, and Berthold, Duke of Zahringen, a nephew of the empress. From the sources it appears that these soldiers were mounted men-at-arms – knights and sergeants – seemingly without any attendant infantry. Traditionally, the infantry should have been there, and why they were missing is not explained in the original sources.

There are several possibilities; perhaps it was because of the speed Frederick required of them; perhaps the Germans normally had their infantry supplied by local allied Italians or mercenaries; or perhaps Frederick Barbarossa felt that cavalry reinforcements were what his army needed at the time. Too little is known about Fredericks military organization or his needs on this campaign to determine the reason why there were no infantry among these reinforcements. But had they been present, the Battle of Legnano would probably have turned out differently.

MANOEUVRES

The emperor was at the head of his own 500 cavalry, and these joined the German reinforcements at Como early in May. This was certainly not the entire German army at Frederick’s disposal in Italy at the time, and it may be that the 500 cavalry were only his bodyguard, who accompanied the Holy Roman Emperor to protect him on the journey to meet up with the Swabian and Rhenish reinforcements.

If this was the case, then Frederick likely wanted to add these to his army so that he might campaign more effectively against the Lombard League. He may even have felt that such a large cavalry army, all equipped in heavy armour on powerful, expensive horses, might intimidate the Italians into surrender without the need for military action – the most successful campaign is the one that brings its desired result without actual fighting.

But Frederick’s main army was at Pavia at the time, putting the town of Milan between this force and those with him. Frederick hoped that he might be able to travel around Milan without meeting opposition from the Lombard League.

However, the Milanese knew exactly where the two German armies were, and they also recognized that Frederick’s division of his forces offered them an extraordinary opportunity. The Milanese governors mustered the town’s forces – probably any man who could bear arms – and also called in numerous neighbouring allies to join them. German narrative sources place these troops at 12,000 cavalry, with an even larger number of infantry, but these tallies are surely exaggerated. Modern historians have suggested the number to be closer to 2000 Milanese cavalry, with no more than 500 infantry, the latter drawn from Milan, Verona, and Brescia. Present also was Milan’s carroccio, a large ceremonial wagon that symbolized the wealth and independence of the city.

THE BATTLE

Not wanting the two German armies to unite, the Milanese moved to intercept them. This occurred outside Legnano on 29 May. From the original sources, it appears that the Italian army-which had effectively concealed their movement behind a forest – actually surprised Frederick Barbarossa. Before the emperor could organize his battlefield formation, the vanguard cavalry of the Milanese, numbering around 700, charged into the German vanguard cavalry, which numbered considerably fewer, probably no more than 300. The Germans were quickly routed. But they had bought some time for their army to form up, which quickly took in those retreating and chased off their pursuers.

During this action, the Milanese had also moved onto the battlefield and formed their lines opposite the Germans. The cavalry was ordered in four divisions, with the infantry and carroccio behind these. How the German army was arrayed is not revealed in the contemporary sources. Frederick decided that it was to his benefit to go on the offensive, as he was in `foreign’ territory and could not count on his forces being relieved, while he feared that his opponents’ numbers would only increase if he delayed for too long. He also refused to retreat, although this may have been the wisest strategy at the time; the Annals of Cologne claims that the emperor counted `it unworthy of his Imperial majesty to show his back to his enemies’. So, instead of taking a defensive Stance, the German cavalry charged `strongly’, and their attack quite easily broke through the Milanese cavalry.

INFANTRY STAND FAST

However, pushing through the cavalry, the Germans ran into the Italian infantry, who had held their positions despite the flight of the cavalry – an important and incredibly courageous stand. The German cavalry charge was halted. The Italian infantry – `with shields .set close and pikes held firm’, states Archbishop Romuald of Salerno – caused the German horses to stop, unable to penetrate the massed infantry, and unwilling to run onto their long spears. This was not surprising, because such a result had happened before: if horses could not penetrate or go around an infantry line, they simply stopped. But it was a result that could only come about when the infantry was motivated to stand solidly and not flee, even when they faced soldiers whose armour and warhorses displayed a wealth and power attainable by very few’, if any, foot soldiers. In the twelfth century, such a stand was rare.

The stubborn courage of the Milanese infantry allowed their fleeing cavalry to regroup and return to the battlefield, where they attacked the halted German cavalry in the flank. Frederick’s horsemen, seeing that the charge that hail so recently brought success against their cavalry counterparts had been stopped by lowly infantry, began to waver. They quickly turned from their fight with the infantry and attempted to return to their former positions. But this retreat was very disordered and, lacking their own infantry to regroup behind, it quickly turned into a rout. Some time during this part of the battle, Frederick’s banner was lost to the Milanese, and his horse was killed under him.

Frederick barely escaped – although how is not recorded in the original sources – and for several days, while he made his way secretly back to Pavia, it was feared that he had been killed at Legnano. Many Germans were captured, but the total number of either army slain on the battlefield seems not to have been large, undoubtedly a testimony to the protection given by the mail armour worn by the German and Milanese men-at-arms.

Few battles show the necessity of medieval armies to have both cavalry and infantry on the battlefield better that the Battle of Legnano. The Milanese had both infantry and cavalry in their army, and it was their infantry who were able to hold against the charge of the German cavalry. This gave them victory at Legnano. Frederick Barbarossa had not fielded a similarly organized army, leaving no relief for his cavalry when they began to flee, and this more than anything else decided his defeat.

AFTERMATH

Their victory at the Battle of Legnano brought immediate results for the Italians. By October, Frederick was forced to sign the Treaty of Anagni with Alexander III, recognizing him as pope and giving him numerous concessions. And the following May, Frederick signed the Treaty of Venice, making a truce with the Lombard League and the Kingdom of Sicily.

Furthermore, over the following few years, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa was forced to become more involved in affairs in Germany. Another campaign across the Alps was, at least for the time being, unthinkable, and in June 1183 the emperor again made peace with the Lombard League, under the Treaty of Constance, which granted nearly complete sovereignty to its members.

Although Frederick and his successors returned to Italy, they were never able to break the desire for independence among those towns in the north which had experienced this self-government. One might conclude then that at Legnano the Renaissance was horn.