The British never seemed to have the problems the US Navy did about taking the Corsair to sea. The FAA “circular approach” for a carrier landing allowed the pilot to keep the deck in sight over the long nose right up to landing, and was eventually adopted by the US Navy when Corsairs finally joined the fleet in 1945. Even the F4U-1 “birdcage” Corsair Is were regularly flown off British escort carriers during initial training in 1943 while the US Navy claimed the aircraft was incapable of operating off an Essex-class fleet carrier, and the FAA did so without the modifications to the oleo strut air pressure and the starboard wing spoiler for stall warning, though these modifications did show up with the widely-used Corsair II, the first version to go into combat. Additionally, the British Corsairs after the Corsair I had eight inches clipped from each wingtip to enable them to be stowed with wings folded aboard British fleet carriers with their smaller hangar compartments; this resulted in a higher roll rate and lessened the airplane’s tendency to float on landing. The first carrier combat missions were flown by Corsairs of 1834 and 1836 squadrons of Victorious’ 47 Naval Fighter Wing in Operation Tungsten, the Home Fleet strikes against the German battleship Tirpitz in Norway in April 1944. The Far East debut of Corsair carrier combat operations came a week later when Illustrious’ 1830 and 1833 squadrons of 15 Naval Fighter Wing attacked Sabang.

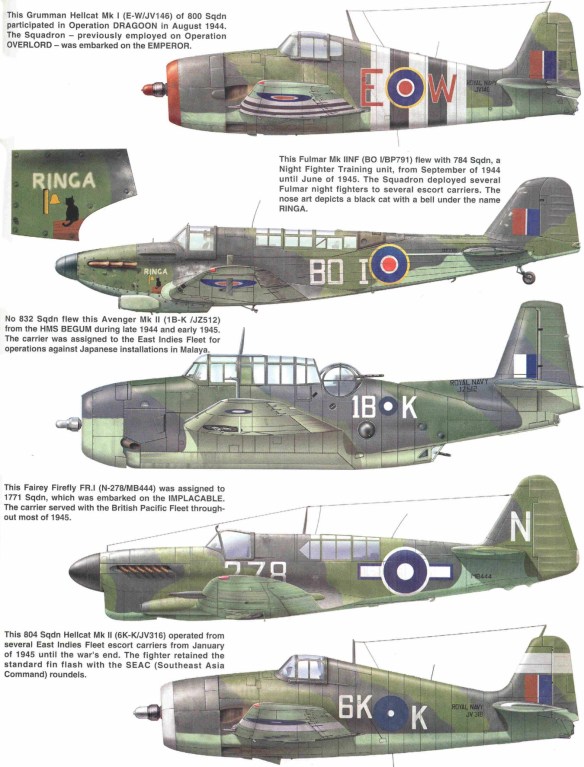

Second to the Corsair in terms of widespread first line service was the Grumman F6F Hellcat, originally named “Gannet” after a large North Atlantic seabird. Universally known to its pilots regardless as the Hellcat, the British fighters took the name officially in March 1944 when the FAA adopted the official US Navy names for their US aircraft. Beginning in May 1943, 252 F6F-3s were supplied to the Fleet Air Arm as the Gannet I under lend-lease, with an additional 930 F6F-5s delivered after August 1944 as the Hellcat II; some 100 were delivered as the Hellcat PR II, modified similarly to the F6F-5P for photo reconnaissance, while a further 80 radar-equipped F6F-5Ns were delivered as the Hellcat NF II.

800 Squadron was the first FAA unit to operate the Hellcat, taking delivery of its first aircraft in July 1943 and flying the first antishipping strikes off the Norwegian coast from the escort carrier HMS Emperor in December in company with 804 Squadron, the second unit to re-equip with the Hellcat. The squadrons flew escort for the first strikes against the Tirpitz on April 3, 1944. Over Norway on May 8, 1944, 800 and 804 squadrons came across a formation of Bf-109Gs and Fw-190As from the Luftwaffe’s Jagdgeschwader 5. The Hellcats shot down two Bf-109s while Lt Blyth Ritchie, a Mediterranean Sea Hurricane veteran who had previously scored 3.5 victories in 1942, bagged a Fw-190. Six days later, on May 14, Ritchie became the first FAA Hellcat pilot to “make ace” when he shot down a He-115 seaplane and shared a second with 804 squadron commander LCDR Stanley Orr. These were the only Hellcat victories scored by the FAA in the European theater.

800 and 804 squadrons participated in Operation Dragoon, the Allied landings in the south of France in August 1944. This turned out to be the final FAA Hellcat operation of the European Theater. The next month, the two squadrons were combined as 800 Squadron; Emperor and her Hellcats transited the Suez Canal and joined the Far Eastern Fleet. During October and November, 888 Squadron joined 800 aboard Emperor, flying Hellcat FR II photo recon fighters, and the two squadrons flew strikes against Japanese positions along the Burmese and Malayan coasts and the Andaman Islands. FAA Hellcats had already gone to war in the Indian Ocean that August, when HMS Indomitable arrived with the Hellcat-equipped 1839 and 1844 squadrons of 5 Naval Fighter Wing.

The final American aircraft on the decks of the British Pacific Fleet’s carriers was the Grumman TBF Avenger. The FAA had quickly seen the Avenger’s value as a strike aircraft and deliveries under lend-lease began in late 1942. Initially named “Tarpon” for the large Atlantic fish, the name was changed to Avenger in January 1944. Grumman built 402 TBF-1Bs, which were actually the TBF-1 and the TBF-1C sub-types, without further differentiation as the Tarpon I; 334 Eastern Aircraft-built TBM-1Cs were taken on as the Avenger II, with 222 TBM-3s as Avenger IIIs. The FAA learned to differentiate their Avengers by production source, as they did with the Corsair, after discovering that the “same aircraft” built by different manufacturers was not really the “same aircraft.” While the US Navy re-equipped its units completely with ever-newer versions of the Avenger, all the British Avengers were used throughout the war, with squadrons operating both Avenger Is and Avenger IIs simultaneously, distinguished only by their different camouflage schemes (Grumman-built Avenger Is used the correct FAA-approved camouflage colors of dark slate gray, extra-dark sea gray and sky, while the Eastern Aircraft-built Avenger IIs were painted in US “equivalent colors” of olive drab, neutral gray and sky gray, respectively).

While the American aircraft were the majority of the fleet’s air arm, there were also three British designs on the fleet’s flight decks.

The Fairey Barracuda was an ungainly-looking shoulder-wing monoplane used as both a dive and torpedo bomber. The Barracuda was Fairey Aviation’s second attempt to create a modern replacement for the venerable Swordfish torpedo bomber that gained fame attacking the Italian fleet at Taranto in November 1940 and damaging the German battleship Bismarck sufficiently that the battleships of the Home Fleet could catch their German opponent and sink her in May 1941. The open-cockpit biplane Swordfish was obsolete when it entered service in 1934, but went on to be one of five British aircraft in front-line service in 1939 that were still serving in 1945 as it flew off the smallest escort carriers, in weather so appalling other aircraft were chained to their decks.

Fairey submitted the design in response to Air Ministry Specification S.24/37 for a three-seat torpedo and dive-bomber aircraft. The first prototype flew on December 7, 1940.

The aircraft used Fairey-Youngman trailing-edge flaps to come aboard at a safe speed. Lowering these large flaps to reduce speed in a dive-bombing attack disturbed the airflow over the rear of the airframe, which necessitated the strange high-set tailplane. The most important sub-type was the Barracuda Mk.II, powered by a 1,640hp Merlin 32; 1,688 rolled off production lines at Fairey, Blackburn, Boulton-Paul and Westland line between 1942 and 1945.

On April 3, 1944, 42 Barracudas took part in Operation Tungsten, their first combat operation. The bombers arrived over Alten Fjord, Norway, at the very moment Tirpitz was about to depart her anchorage for sea trials. Their dive-bombing attacks scored 24 direct hits, damaging the battleship so badly it was out of action for several months for repairs. Other attacks in the summer of 1944 were less successful. The Barracuda arrived in the Far East with 810 and 847 squadrons aboard Illustrious.

Victorious operated a Barracuda squadron and all three units took part in the oil strike operations that began in August 1944.

The Fairey Firefly I continued the design philosophy of the preceding Fulmar in having a dedicated navigator-radioman as a second crewman. The design was the result of FAA Specification N8/39, which called for a two-seater armed with either four 20mm cannon or eight .30-caliber machine guns using the then-new and untried Rolls-Royce Griffon, issued in July 1939 while the Fulmar prototype was still under construction. Fairey’s response was a somewhat smaller, Fulmar-type aircraft with 20mm cannon and an empty weight barely less than the Fulmar’s loaded weight. Specification N5/40 was written around the mock-up after it was inspected and approved on June 6, 1940. The first Firefly I flew on December 22, 1941. The aircraft used the Fairey-patented area-increasing Youngman flaps, which gave the necessary maneuverability in air combat and lowered the heavy aircraft’s landing speed for carrier operation. The first production aircraft was delivered on March 4, 1943, which was a very respectable timetable for wartime aircraft development. Every other British-designed carrier aircraft ordered in the same timeframe ran into development difficulties and none flew before the end of the war. The Firefly was thus the only British-designed modern high- performance carrier aircraft to operate off British carriers in the war it was designed for.

Unfortunately, the Firefly lacked the performance to operate in its designed role of fleet defense fighter, even with the 1,735 horsepower of the Griffon IIB. The greatest fault in the design lay with the choice of placing the radiator in a large cowling directly beneath the engine, resulting in a high-drag configuration, and the requirement for a second crew member, which added weight. With a top speed of only 319mph and a climb rate under 2,000 fpm, though it had a useful range of 774 miles on internal fuel, the Firefly I was used as a strike and tactical reconnaissance aircraft, a mission for which it was more than capable. A Firefly I tested at the US Navy test center at NAS Patuxent River in 1944 more than held its own in air combat maneuvering against the F6F Hellcat; those flaps worked.

1770 Squadron was first to be formed on the Firefly in October 1943, followed in February 1944 by 1771 Squadron. 1770 went aboard HMS Indefatigable and gave the type its baptism of fire in Operation Mascot, the failed attack against Tirpitz on July 17, 1944. That November, Indefatigable and 1770 Squadron, led by Major Vernon “Cheese” Cheesman, joined the British Pacific Fleet.

Indefatigable’s 24 Naval Fighter Wing operated the legendary Supermarine Seafire. The navalized Spitfire first joined the Royal Navy in late 1942 and entered combat in the summer of 1943, providing the primary air defense for the Allied fleet at Salerno that September. The Mk I and Mk II sub-types were minimal conversions of land-based Spitfires equipped with an A-frame arrestor hook under the rear fuselage and catapult spools. Without folding wings, these Seafires could not be struck below on a carrier; all maintenance at sea took place on the open flight deck.

The F. Mk III was the first fully-navalized Seafire, first flown in November 1943. Cunliffe-Owen, the company responsible for modifying the Seafire I and Seafire II, developed a folding wing for the Seafire III, which allowed below deck stowage. The L. Mk III, powered by the Merlin 55M engine with a cropped impeller to give maximum performance below 5,000 feet, quickly replaced the original F. Mk III. At low altitude, the Seafire III outperformed the A6M5 Zero when tested against each other. The aircraft had a superior low-altitude climb rate and acceleration to either the Hellcat or Corsair, which made it the best low-altitude short-range fleet interceptor available in the Pacific. 887 and 894 squadrons, the most-experienced Seafire units in the Royal Navy, went to the Pacific aboard HMS Indefatigable.

The Royal Navy’s carriers had been developed for a different kind of war than had those of the US Navy. The British ships were designed for operation in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, where they did not need the range and sea-keeping ability of the American carriers. Since their opponents would be land-based aircraft that were expected to outperform the defending carrier fighters, the ships were designed with an armored flight deck, and with much more armor throughout the ship than was the case with the Essex-class ships. The result for the British was that their hangars did not open on the sides as with the Essex carriers, which meant that aircraft could not be run up on the hangar deck to speed up the launch of multiple strikes. A British naval air group numbered only some 45–50 aircraft, as opposed to the 90-aircraft force on an Essex-class carrier. The Americans initially derided the British carriers with their heavy armor and reduced capacity, but when the kamikazes became the primary threat, the ability of a British carrier to shrug off a hit that would have heavily damaged if not sunk outright an American carrier rightly impressed the Americans, who adopted this feature in their postwar carrier designs.

On January 1, 1945, the BPF carriers left Trincomalee to undertake their last strike from the old base, Operation Lentil. HMS Indomitable, Victorious and Indefatigable, escorted by the cruisers HMS Suffolk, HMS Ceylon, HMS Argonaut and HMS Black Prince, launched an attack on January 4, 1945 against the former Royal Dutch Shell refinery at Pangkalan Brandan in northern Sumatra. Ninety-two Avengers and Fireflies, escorted by Hellcats of Indomitable’s 1839 and 1844 squadrons and Corsairs from Victorious’ 1834 and 1836 squadrons, targeted the installation.

Sixteen fighters sent ahead as a “Ramrod” attacked the airfields at Medan and Tanjong Poera. 1834 Squadron’s Leslie Durno spotted a Ki.46 Dinah twin-engine reconnaissance plane with wheels and flaps down for landing at Medan Airfield. Durno and his wingman attacked the Dinah and damaged it, then Durno turned in astern of the enemy plane and fired a five-second burst that staggered the Dinah before it blew up at the edge of the runway. Minutes later, he spotted a Ki.21 Sally bomber, which he set afire with an eight-second burst. This victory made Durno both the first FAA Corsair ace and the first FAA pilot to score five Japanese victories.

The strike force was launched 90 minutes after the fighter sweep, with 32 Avengers and 12 rocket-firing Fireflies escorted by 12 1836 Squadron Corsairs to bomb the refinery. Several Oscars attacked the strike force at 0850 hours. Sub-Lieutenant D. J. Sheppard, RCNVR, of 1836 Squadron, Number 3 in Wing Leader Ronnie Hay’s flight, was able to latch onto an Oscar in the swirling dogfight and shoot it down. He later reported, “The Jap’s cockpit seemed to glow as I hit him with a long burst, and I could see the bullets striking the engine and cockpit. He leveled out at 300 feet and then went into a climbing right turn. I fired again and the pilot baled out as the aircraft rolled over and went into the sea.” Ten minutes later he spotted a second Oscar and closed in before opening fire. The Oscar blew up under the weight of his fire. Sheppard had scored two in his first combat.

The strike force inflicted heavy damage on the refinery and oil storage tanks, while a small tanker was set on fire and two locomotives were hit. Two aircraft were lost to antiaircraft fire, but the crews were rescued.

Following the fleet’s return to Trincomalee, the British Pacific Fleet weighed anchor and headed east-southeast into the Indian Ocean on January 16 on the first leg of its transfer to the Pacific theater of operations. The slow and awkward Barracudas were gone from the strike squadrons, replaced with Grumman Avengers. Admiral Vian’s Task Force 63 planned a final strike against the Indonesian oil refineries during their passage to Australia, called Operation Meridian One. The targets were the Palembang refineries at Pladjoe and Songei Gerong. Bad weather over the Indian Ocean delayed the strike from January 22 to 24.

Illustrious, Victorious, Indomitable and Indefatigable began launching their strike aircraft at 0600 hours on January 24, 1945: 43 Avengers and 12 Fireflies, escorted by 48 Hellcats, Corsairs and Seafires, headed for the Pladjoe refinery while 24 Corsairs were assigned to sweep the airfields at Lembak and Tanglangbetoetoe. Victorious’ Major Ronnie Hay was assigned as the strike coordinator leading a top cover of 12 Corsairs. 12 Fireflies of 1770 Squadron were assigned as close escort for the Avengers, led by Major Cheesman, each armed with eight 60lb rockets for flak suppression. Eight Corsairs from 1830 Squadron formed the middle cover, while eight Corsairs from 1833 brought up the rear.

Japanese radar picked up the strike force over Sumatra. Lieutenant Hideyaki Onayama led twelve Ki.44 Tojos from the 87th Sentai (regiment) to intercept the strike force some 20 miles west of the refinery. Hay scored his first Pacific victory when he spotted a Tojo approaching from out of the sun. The Tojo flashed past and Hay dived after it. “After a five-minute chase I caught up with him at nought feet and 250 knots. I gave him a two-second burst which hit his engine and he crashed but did not burn.” Hay climbed back to altitude to coordinate the strike, and ran across another Tojo and shot it down. Sub-Lieutenant Sheppard also shot down a Tojo. More Oscars joined in the fight, while Japanese antiaircraft batteries below opened fire as the attackers neared the target.

Just before the first Tojos struck, Major Cheesman’s engine began running rough and he was forced to pass leadership of the 1770 Squadron Fireflies to Lieutenant Dennis Levitt and return to Indefatigable. Moments later, the Fireflies came under attack by Oscars of the 26th Sentai. They turned into the enemy fighters and Levitt shot down the first enemy aircraft to fall to the Firefly, while Sub-Lieutenant Phil Stott shared a second with his wingman, Sub-Lieutenant Redding.

Hellcat pilot Sub-Lieutenant Edward Taylor shot down a Tojo during the fight. When added to his previous victories in the Mediterranean, he became the only South African Navy ace. Minutes later, he shared the destruction of a Ki.45 Nick twin-engine fighter from the 21st Sentai with his wingman.

The fierceness of the air battle is shown by claims for 14 Japanese aircraft shot down and six probable kills. The Corsairs that struck the airfield destroyed 34 enemy aircraft and damaged a further 25 on the ground. Despite the presence of protective barrage balloons that forced the Avengers to drop their bombs from 3,000 feet, the refinery was successfully hit. Fleet air losses were heavier than previous raids: seven aircraft were shot down over the target and 25 aircraft – many damaged from antiaircraft fire – were lost in crash landings back aboard the carriers. The attack cut output at the refinery by 50 percent for three months, with most of the refined oil in the storage tanks destroyed by fire.

The fleet rendezvoused with the tankers again over January 26–27. Owing to poor weather and inexperience, the tankers suffered damage as ships being refueled failed to keep station and hoses parted, greatly delaying the operation.

On January 29, the carriers returned for Operation Meridian Two, a strike against the refinery at Songei Gerong, Sumatra. Poor weather gave low visibility and the strike force launch was delayed for 25 minutes by a rain squall. Once again, Ronnie Hay acted as strike coordinator.

Defensive aerial opposition was strong; pilots claimed 30 shot down with another 38 destroyed on the ground, for the loss of 16 British aircraft. Just after the Avengers made their bombing runs, Hay was attacked by a Tojo he quickly downed, then an Oscar that tried to latch onto his tail as the Tojo fell burning.

Hay’s element leader, Don Sheppard, also claimed two in this fight to become the second Corsair ace and the only one to score all his victories in the F4U.

The fleet came under attack from the “Shichisi Mitate” Special Attack Corps. Major Hitoyuki Kato led seven Ki.21 Sally and Ki.48 Lily bombers in low-level suicide attacks. New Zealander Sub-Lieutenant Keith McLennan, who manned the alert Hellcat of 1844 Squadron aboard Indomitable, was launched to intercept the kamikazes. Within minutes of retracting his landing gear, McLennan was in the middle of the enemy bombers and shot down two in quick succession, then shared a third with Seafire pilot Sub-Lieutenant Elson of 894 Squadron. With a total of 3.5 victories, McLennan was the most successful New Zealand Navy pilot of the war.

Meridian Two stopped all production at the Songei Gerong Refinery for two months, and, over the rest of the war, production was never more than a quarter of pre-attack levels. For the loss of 25 aircraft in the three January operations, production of aviation gasoline on Sumatra was cut to 35 percent of its pre-attack level. The shortage would have a dramatic effect on the Burma campaign in the final six months of war. These strikes, coming as they did in coordination with Halsey’s South China Sea strikes, meant Japan was now almost completely cut off from petroleum supplies, the control of which were the major reason why Japan had gone to war in 1941.

The British Pacific Fleet arrived in Sydney, Australia, in mid-February and began preparations to join the US Navy in the coming invasion of Okinawa.