Swedish field marshal. Johan Banér was born in Djursholm Castle, Sweden, on July 3, 1596. His father and uncle were both beheaded in 1600 on a charge of treason against the Crown. Despite the fact that Gustavus Adolphus’s father had ordered Banér’s father executed, Banér developed a close friendship with King Gustavus Adolphus when the latter reinstated the Banér family following his accession to the throne in 1611. Banér entered the Swedish Army in 1615 and fought in the Swedish Siege of Pskov that same year during the Russo-Swedish War of 1613–1617. He then participated in the Polish-Swedish War of 1617–1629. Banér was promoted to cornet in 1617, to captain lieutenant in 1620, and to colonel in 1622. During 1625–1626 he commanded the fortress of Riga, and he then took part in a number of battles against the Poles. During 1629–1630 he was governor of Memel (Klaipéda).

In 1630 when Gustavus Adolphus entered the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) in Germany as the Protestant champion and to secure territory and influence for Sweden, Banér was a general and one of his chief lieutenants. In the Battle of Breitenfeld (September 17), Banér commanded the right-wing Swedish cavalry. Shortly thereafter he became Gustavus’s chief of staff. Banér took part in the capture of Augsburg and of Munich and distinguished himself in the Battles of the Lech (April 15–16, 1632). He was wounded in the unsuccessful Swedish assault on General Wallenstein’s camp at Alte Veste (September 3–4). When Gustavus moved on Lützen, he left Banér in command of Swedish forces in western Germany, where Banér opposed the imperial general Johan von Aldringen.

Banér was promoted to field marshal in February 1634. Acting in concert with a Saxon army, he invaded Bohemia and moved against Prague but was halted by the complete defeat of Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar and Field Marshal Gustav Horn in the Battle of Nördlingen (September 6, 1634). The ensuing Peace of Prague (May 30, 1635) placed Sweden in a dangerous position. In early 1635 Banér took command of all Swedish forces and won a victory in the Battle of Wittstock (October 4, 1636), restoring Swedish fortunes in central Germany. Swedish forces were decidedly inferior in numbers to those of their opponents, and Banér, after rescuing the garrison of Torgau, was forced to withdraw across the Oder River into Pomerania in late 1638.

In 1639 Banér’s reorganized Swedish forces again overran northern Germany, defeating the Saxons at Chemnitz (April 14, 1639) and even invading Bohemia and threatening Prague. Then, in a daring and highly unusual winter campaign in 1640–1641, Banér joined with French forces commanded by the Comte de Guébriant and attacked Regensburg, seat of the Holy Roman Empire, but was unable to capture the city. Harassed by imperial forces, Banér then withdrew to Halberstadt, where he died on May 20, 1641, probably from pneumonia contracted during the retreat. A bold general and a thorough disciplinarian who was nonetheless well respected by his men, Banér was a worthy chief of staff to Gustavus Adolphus.

Further Reading: Parker, Geoffrey. The Thirty Years’ War. New York: Military Heritage Press, 1987. Steckzén, Birger. Johan Banér. Stockholm: H. Gerber, 1939.

The Battle of Wittstock

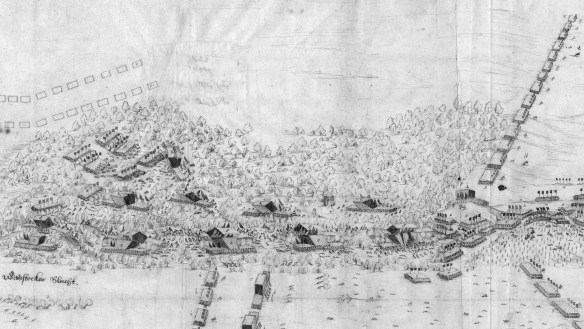

The Battle of Wittstock. The Swedish army prepares for its assault on the wood defenses of the Allied center and left flank before Wittstock.

Initial Swedish attack and Imperial realignment.

Swedish breakthrough and Imperial retreat.

The Battle of Wittstock fought just south of the small northern German town of Pomerania on 4 October 1636-was one of the most important in the Thirty Years’ War. 1 The battle was between a Protestant Swedish Army of fifteen thousand, comprised of nine infantry brigades and fifty cavalry squadrons, and their Catholic opponents, an Allied Army of some twenty thousand that included thirteen infantry brigades, seventy cavalry squadrons, and thirty-three guns. The Swedish Army was commanded by the very able General Johan Banér. The Allied Army, an alliance between Saxony and the Holy Roman Empire, had no commander. The battle was deployed on a ridge facing south and southeast with a six-ditch earthen defense system and a wall of linked wagons in the center; on the left was a wooded hill and further east the river Dosse. On the Allied right lay a heath and the large, dense oak forest of Heiligengrab. The imperial contingent under Marazinno held the Allied right; Saxony’s Elector, John George, commanded the center with the artillery; and a brave but not very competent Saxon general, Melchior von Hatzfeldt, was in com- mand on the left. The quality of the Saxon contingents was mediocre.

The overall Swedish position in northern Germany was in serious danger. The Elector of Saxony had joined the imperial cause, and the Swedes retained only a small bridgehead in the north. The Swedish force, screened by thick woodlands, advanced on Wittstock from the south and crossed the Dosse River. General Banér, despite his numerical inferiority, launched an attack on the center and both flanks, using the tree-covered hills to best advantage. Recognizing his opponent’s strength in the center, Baner’s ploy was to approach the enemy concealed by the sandy, tree-covered hills, to mount an attack on the hill on the Allies’ left flank, and then to move in on the centre, thereby weakening the Allies right flank and the right-side detachments of the center. At the same time a quarter of his force was to be deployed in a seven-mile ride encircling the Heiligengrab Forest to mount a surprise pincer attack on the Allied center and rear. The fighting on the Allies’ left of center proved very severe, and the cavalry force, led by a Scots officer named James King, was delayed on its ride first by the marshy terrain and then by the trees and roots in the forest, arriving to save the day only in the nick of time. The Swedish cavalry, pouring out from around the edges of the forest, managed to completely surprise its opponent, first easily disposing of the screen of one thousand German musketeers and then descending on John George’s and Hatzfeldt’s center and rear, capturing their artillery. Dusk and darkness prevented the Swedes from fully following up on their success, but their achievement was nevertheless considerable. The Allied force withdrew in some disorder, losing more men in Banér ‘s pursuit the following day.

Sweden’s important position in northern Germany and its military reputation were restored; the victory, both spectacular and historic, was described with little exaggeration as a classic case of good command and control. The Battle of Wittstock thus made Sweden one of the winners in a war in which many of the other countries involved were massive losers.