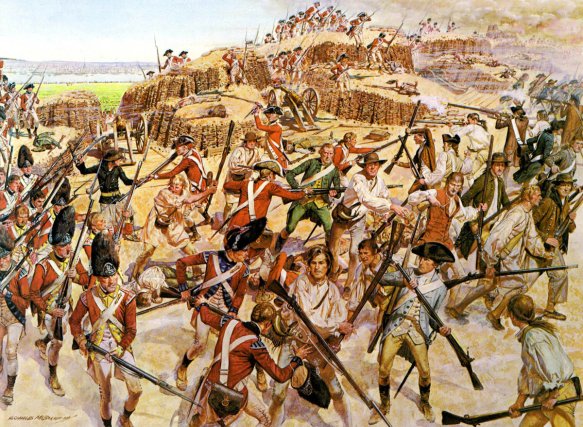

British Attack on Breed’s Hill: Battle of Bunker Hill on 17th June 1775.

General Washington received details of the Battle of Bunker Hill from couriers as he began a ten-day journey with his staff and an escort of five hundred militia on June 23. Crossing heavily Loyalist New Jersey, he pulled a purple smock over his navy-blue uniform and donned a hat with a plume. At New York City, a crowd turned out to cheer him; one hour later, another crowd, including many of the same people from the first, hailed the British royal governor, General Sir William Tryon, returning from England with orders to suppress the rebellion. Washington’s second-in-command, Hudson River land baron Philip Schuyler, told him that New York would not be safe so long as the British could counterattack down the Hudson. Schuyler, general in chief of the Northern Department, agreed to lead a full-scale invasion of Canada to seize Montreal and Quebec before the British could reinforce from England. Congress had unanimously authorized a preemptive invasion if the intrusion was “not disagreeable to the Canadians.”

Washington arrived without ceremony at Cambridge, Massachusetts, on Sunday, July 2, and set up temporary headquarters in a single spare room in the house of the president of Harvard College. Riding the lines, he quickly grasped the army’s weakness. Despite a four-to-one numerical advantage, he had no cannon, no military engineers, very little gunpowder. Washington deplored the conditions he found: 16,000 men living in a shantytown of huts made of sod, planks and fence rails or tents made of linen or sailcloth. Most only had the clothes they had worn when they left home weeks before—homespun breeches, rough linen shirts, leather vests—and carried the family firelock. He found a paucity of nearly everything: uniforms, muskets, gunpowder, cannon, picks, shovels, tents. At his first council of war he was informed by his officers that it was becoming hard to find any new recruits other than “boys, deserters and negroes.” Each New England colony officially forbade black men, indentured white servants or apprentice boys; Washington barred the continued service of Indians. In Virginia, Washington had preached an end to the importation of slaves; in Massachusetts, he now was gratified to see how many freed blacks had enlisted.

Where scores of men had been digging trenches, he put thousands to work. He discovered that there were no trained sergeants and few officers to teach the myriad routines of military life and discipline. Fuming about using the “exceedingly dirty and nasty” New Englanders to oppose the spit-and-polish British professionals a mile away, he blamed an “unaccountable kind of stupidity” on “the levelling spirit” and the “principles of democracy [that] so universally prevail.” Washington saw himself—and the British saw him—as the Oliver Cromwell of the revolution. Like Cromwell, he was an aggrieved member of the country gentry engaging in a civil war, with the virtuous American colonies oppressed by a corrupt court. But in this case, Parliament was choosing to serve an errant king and finding it necessary to put a powerful army in the field to compel his reforms.

When no more attacks came from the British, Washington reasoned that Howe was waiting for reinforcements. In the meantime, he could use his superiority in manpower to take the offensive. He urged Schuyler, with 4,000 Connecticut militia, to accelerate the Canadian invasion. Not the scantest quantity of gunpowder could be found in New York, Schuyler argued. Governor Trumbull scavenged five hundred pounds of gunpowder from Connecticut’s town stocks and managed to send Schuyler £15,000 as well as four hundred barrels of pork. It was August 30 before Schuyler’s forces disembarked on Canadian soil, and there they waited for him—he wrote Washington that he was suffering from an attack of rheumatic gout. Schuyler lost another full month when Connecticut troops at Fort Ticonderoga refused to serve under New York officers and a promised Vermont regiment failed to materialize.

The delays also set back Washington’s plan for a simultaneous surprise attack—led by Benedict Arnold—on Quebec from the rear, which they would approach through the trail-less Maine wilderness. To win Washington and the command over, Arnold had produced the journal of a captured British engineer who had mapped the Kennebec region of Maine.

On the hot gray Sunday morning of September 3, 1775, the Continental Army formed up for Washington’s inspection of the ten-mile cordon of fortifications investing Boston. Washington, his aides and brigade commanders and Arnold, in his red Connecticut Foot Guards uniform, appeared to study every man, every musket. A chaplain later wrote:

The drum beat in every regiment.… All was bustle.… The whole army was paraded in continued line of companies. With one continued roll of drums, the general-in-chief with his staff passed along the whole line, regiment after regiment presenting arms.

Many of the men had tired of the heat, the boredom, the grind of camp life. The prospect of action, especially in a cooler place, excited those who had fought only once in five months. Washington had appointed Arnold a colonel of the Continental Army and allowed him to pick the troops who would march to Quebec before the British could reinforce it—only 775 redcoats held the vast province. After the review, Arnold visited each regiment; forming the men in squares, he explained his need for volunteers. By noon he had 6,000, five times what he needed. He chose men under thirty and above average height. Today, every man was an expert woodsman and boatman. By nightfall, he had a full regiment of 1,050 men.

Washington was happy to see the riflemen go: while their guns could hit a man in the head at a mile and a half, these “shirt-tail men” in hunting shirts and moccasins had been robbing farms and fellow soldiers and violating military etiquette by sniping British officers at long range against Washington’s explicit orders. Washington arranged for a fleet of eleven fishing vessels to take Arnold’s newly minted regiment of rangers from Newburyport, Massachusetts, to the mouth of the Kennebec River. The little army would march overland and then sail up the Kennebec as far as Gardinerstown, where 220 shallow-draft boats were being built to carry men and supplies all the way to within 100 miles of Quebec City. He expected the march to take only twenty days. So confident was Washington that the expedition would succeed, when he finally informed Congress, he grossly underestimated the distance and the difficulty of the march. In his orders, he emphasized that the American invaders were to “consider yourselves as marching, not through an Enemy’s Country; but that of our friends and brethren.” He ordered punishment for “every attempt to plunder or insult any of the Inhabitants.” He gave Arnold a strongbox of gold and silver coins. They were to buy everything with cash, stealing nothing.

From the beginning, everything went wrong. Washington had refused the aid of Penobscot Abenaki guides and the expedition got lost. The captured British map turned out to be a fraud. The bateaux had been made of poorly caulked green wood and had all sunk before the expedition reached Canada—which it did in sixty days, the men nearly starved, not in twenty. Fully a third died or deserted. The entire rear guard mutinied and returned to Cambridge. Washington court-martialed Major Robert Enos but all the witnesses were in Canada. Arnold arrived at the St. Lawrence three days too late. Loyalists, Scots Highlanders from Newfoundland and New York, had reinforced the city and thoroughly defeated Arnold’s assault. Richard Montgomery, who had finally taken over Schuyler’s command and captured Montreal, had been killed in the attack on Quebec on the last day of 1775. Arnold had been critically wounded and all but 150 of his men killed or taken prisoner. Arnold was besieging the walled city with only a few guns and a few French Canadian volunteers. The Canadian expedition could only be rescued with massive reinforcements, but that was impossible until spring. In the meantime, Washington had lost 900 men and his first offensive.

Washington arranged for a fleet of eleven fishing vessels to take Arnold’s newly minted regiment of rangers from Newburyport, Massachusetts, to the mouth of the Kennebec River. The little army would march overland and then sail up the Kennebec as far as Gardinerstown, where 220 shallow-draft boats were being built to carry men and supplies all the way to within 100 miles of Quebec City. He expected the march to take only twenty days. So confident was Washington that the expedition would succeed, when he finally informed Congress, he grossly underestimated the distance and the difficulty of the march. In his orders, he emphasized that the American invaders were to “consider yourselves as marching, not through an Enemy’s Country; but that of our friends and brethren.” He ordered punishment for “every attempt to plunder or insult any of the Inhabitants.” He gave Arnold a strongbox of gold and silver coins. They were to buy everything with cash, stealing nothing.

From the beginning, everything went wrong. Washington had refused the aid of Penobscot Abenaki guides and the expedition got lost. The captured British map turned out to be a fraud. The bateaux had been made of poorly caulked green wood and had all sunk before the expedition reached Canada—which it did in sixty days, the men nearly starved, not in twenty. Fully a third died or deserted. The entire rear guard mutinied and returned to Cambridge. Washington court-martialed Major Robert Enos but all the witnesses were in Canada. Arnold arrived at the St. Lawrence three days too late. Loyalists, Scots Highlanders from Newfoundland and New York, had reinforced the city and thoroughly defeated Arnold’s assault. Richard Montgomery, who had finally taken over Schuyler’s command and captured Montreal, had been killed in the attack on Quebec on the last day of 1775. Arnold had been critically wounded and all but 150 of his men killed or taken prisoner. Arnold was besieging the walled city with only a few guns and a few French Canadian volunteers. The Canadian expedition could only be rescued with massive reinforcements, but that was impossible until spring. In the meantime, Washington had lost 900 men and his first offensive.

#

When still no British attack came from Boston, Washington pursued other ways to pressure them and ease his own terrible shortages. He issued letters of marque to six privateering ships crewed by soldiers from Massachusetts port towns. At the same time, Congress directed him to commission two ships to interdict British arms shipments from Halifax. The two ships, the Cabot and the Andrew Doria, became the first official U.S. Navy vessels. By year’s end, as Congress authorized more vessels, Washington’s Navy, as it was dubbed, included seven ships with thirteen more scheduled to be built. Congress approved a schedule of prize money to be allotted to officers and crewmen. One-tenth of the money derived from auctioning off captured ships and cargoes was to go to Washington himself for his private use, a typical arrangement for eighteenth-century commanders. The infant navy quickly eased one of Washington’s worst problems, capturing a British ordnance brig carrying 2,000 muskets, 100,000 flints, 20,000 rounds of shot and 30 tons of musket balls.

The nearly universal shortage of munitions, especially gunpowder, proved one of Washington’s more enduring obstacles. Historian Orlando Stephenson notes, “The greater part of the gunpowder stored in the colonial magazines had lain there since the Seven Years’ War, the few powder-mills were in ruins, the manufacture of the explosive almost a lost art.” As Americans’ determination to fight had grown, radical leaders had rushed to procure whatever they could however they could, often by seizing private property or Crown supplies. In December 1774 New Hampshire militia had attacked Fort William and Mary in Portsmouth, seizing 10,100 pounds of gunpowder. In May 1775 the Sons of Liberty appropriated six hundred pounds from Savannah’s powder magazine; in July, they boarded a royal navy ship and carried off 12,700 pounds. In a matter of months, the rebellious colonists secured another 3,000 pounds in New Hampshire, 12,000 in Massachusetts, 4,000 each in Connecticut, Maryland and Pennsylvania and 17,000 in Rhode Island, but heavily Loyalist New York and New Jersey yielded almost none. Under the guise of post office business, Benjamin Franklin, a member of Pennsylvania’s Committee of Safety and a delegate to the Continental Congress, smuggled wagons to Washington’s camp loaded with 4,000 pounds of powder gathered in Philadelphia, stopping along the way to berate his son, William, the last holdout as a royal governor, for refusing to come over to the revolutionary cause.

Washington pleaded for even the smallest quantities. Half of the 80,000 pounds procured in the opening weeks of the war had found its way to the fighting around Boston. By the time Washington arrived, half the powder collected in all the colonies had been expended recklessly. He found only thirty-six barrels at Cambridge. When he took an inventory on August 3, he found only enough powder in the whole army to furnish “half a pound to each man exclusive of what was held in their horns and cartridge-boxes.” By the end of August he could no longer employ his artillery, all his cannon silenced except a nine-pounder he fired peripatetically from Prospect Hill. Looking down on Boston from this vantage point, Nathanael Greene wrote back to Governor Henry Ward in Rhode Island: “Oh, that we had plenty of powder; I should then hope to see something done here for the honour of America.”

Not a single powder mill operated in the British colonies at the outbreak of war. On Christmas Day, 1775, Washington wrote, “Our want of powder is inconceivable. A daily waste and no supply administers a gloomy prospect.” By January, after nine months of war, nearly all the powder found in colonial America had been used up. The scarcity of powder impelled the Second Continental Congress to act with unaccustomed celerity to produce or import an adequate supply. While some delegates maintained that the manufacture of gunpowder was the prerogative of colonial governments, Congress pushed through an elaborate plan for producing saltpeter and powder. John Adams wrote James Warren on June 27, 1775, that “Germans and others here have an opinion that every stable, Dove house, Cellar, Vault, etc., is a Mine of Salt Petre.… The Mould under stables, etc., may be boiled Soon into salt Petre it is said. Numbers are about it here,” he added, sending along the proclamation with instructions for processing that Congress was sending to each colony’s government. After Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill, Massachusetts needed no urging. Every colony passed legislation, promising financial support and handsome bounties for the first to manufacture specified quantities of gunpowder, saltpeter or both, but all sulphur had to be imported.

In January 1776, at Weymouth, Massachusetts, not far from Washington’s headquarters, a group of fledgling chemists celebrated their production of saltpeter before a committee of the Provincial Congress, who deemed it “very good.” In Pennsylvania, merchant Oswald Eve “established the making of powder in this Province which had not been carried on to any extent before.” By the autumn of 1777, saltpeter extracted in each colony enabled production of 115,000 pounds of gunpowder, nearly all of it in 1776 at the peak of revolutionary enthusiasm. Gradually, vast quantities of saltpeter would be imported, mainly from the Netherlands, until, by late 1777, nearly 700,000 pounds of gunpowder was produced from imported saltpeter. Added to 1.5 million pounds of imported gunpowder, American forces had 2.4 million pounds of gunpowder to draw on during the first half of the war, nearly 90 percent of it imported from Europe through Dutch and French colonies in the Caribbean. America was learning how to arm itself.

At the beginning of 1776—that pivotal year of revolution—George Washington was still gloomy about the prospect of equipping an army “without any money in our treasury, powder in our magazines, arms in our stores … and by and by, when we shall be called upon to take the field, shall not have a tent to lie in.” Had Howe known the Americans’ desperate shortages, he might have rolled over the Continental Army and ended the Revolutionary War. As the colonies went to war, they could only find weapons in gun shops, trading houses and private homes, which held an array of muskets, rifles, fowling pieces, pistols and blunderbusses. Some volunteers had no weapons at all, possessing only pikes or swords. What few iron forges existed lay hidden in remote reaches of colonies. In the Pine Barrens of New Jersey, bog iron turned into cannonballs. In Salisbury, Connecticut, a forge founded by Ethan Allen to produce iron caldrons for boiling potash underwent conversion to produce cannon, some at first dangerous only to the gunners themselves. Connecticut also set up a small musket factory at Waterbury; Pennsylvania expanded its weapons industry, centered in Lancaster County and drawing on iron mines and foundries in Warwick, Reading and Carlisle. More commonly, gunsmiths, in towns or on the frontier, worked alone or with one or two apprentices to make highly individualistic weapons—they could only produce, on average, one gun a day. Very few guns except those seized from royal stores matched.

At one point Washington even considered sending hundreds of unarmed militia home before Congress decided to confiscate weapons from Loyalists. In his memoirs, General William Moultrie of South Carolina remembered with awe that the colonists dared resist British might “without money, without arms, without ammunition, no generals, no armies, no admirals and no fleets.” The people of Charleston lacked weapons and ammunition until they broke into royal magazines and took some 1,000 muskets, then seized an English brig carrying 23,000 pounds of gunpowder. The “want of powder was a very serious consideration,” wrote Moultrie, “for we knew there was none to be had upon the continent of America.” In Pennsylvania the Committee of Safety, chaired by Franklin, advertised for weapons in the newspapers. The few cannon available in New York City lined the parapets of Fort George—until King’s College (today’s Columbia University) students led by twenty-year-old Alexander Hamilton dragged them away under fire from the British man-of-war Asia to arm the first artillery company in the Continental Army.

The revolutionaries’ fortunes improved dramatically in early March 1776, when Washington’s putative colonel of artillery, erstwhile Boston bookseller Henry Knox, appeared in camp with sixty pieces of French field artillery captured at Ticonderoga and Crown Point. Waiting until ice and snow paved his route, Knox and three hundred teamsters with their oxen had dragged the cannon first across the frozen Hudson River and then east along the route of the present-day Massachusetts Turnpike. On the morning of March 2, 1776, Washington’s newly acquired artillery opened a booming barrage from the north shore of the Mystic River, diverting British attention away from where 2,000 men were hastily constructing an ice fort out of huge wicker baskets filled with snow and doused with water. By the morning of March 5, the sixth anniversary of the Boston Massacre, American gunners looked down on all of Boston and the entire British fleet. After two days of fierce winds and driving rain, Howe aborted a planned counterattack. By March 7, Howe began evacuating the city, sending off a regiment each day embarked on transports—after the soldiers plundered every shop and house in the town. Crowding onto any vessel they could hire, some 1,100 New England Loyalists and all they could carry joined the retreating British flotilla and sailed into exile at Halifax.

If it hadn’t been for guns and ammunition purchased in Europe and the West Indies, the American Revolution would have collapsed. As early as October 1774, when the British Privy Council banned the importation of weapons to the American colonies, a brisk contraband trade sprang up, centered in St. Eustatius. Gage warned London that colonists were “sending to Europe for all kinds of Military Stores,” some of them from “unscrupulous” British merchants. In the summer of 1775 Maryland’s Convention sent commercial agents to St. Francois in the Caribbean to transship arms purchased in Europe by small vessels. Agents also slipped into France to procure munitions directly from Europe. Pennsylvania’s Committee of Safety followed suit in August, ordering munitions from the French and Spanish West Indies. The few guns produced in Pennsylvania cost twelve dollars apiece, French muskets half that.

In July, a full year before the vote on independence, Congress resolved that any ship transporting munitions for “the continent” could load and export produce in exchange, clearly in defiance of the British Orders in Council. Two weeks later Congress appropriated $50,000 for selected merchants to buy gunpowder for the Continental Army—at a 5 percent commission. By September Congress created the Committee of Secret Correspondence, its members—merchants John Alsop and Philip Livingston of New York and Thomas Willing and Robert Morris of Philadelphia—empowered to draw on the Continental treasury to buy 1 million pounds of powder, 10,000 muskets and 40 field pieces.

In September 1775 Congress created the Secret Committee of Trade, putting Morris in charge of the business side of the war and capitalizing on the commercial contacts of Willing and Morris in Europe. Becoming known as the “financier of the Revolution,” Morris wrote to Connecticut merchant Silas Deane, “It seems to me the oppert’y of improving our Fortunes ought not to be lost, especially as the very means of doing it will contribute to the Service of our Country at the same time.”

As the Treasury dried up, Congress voted to allow exchange with Caribbean islands of cod, lumber, tobacco and indigo for arms and ammunition, and they also commissioned agents to order and funnel supplies from Europe and the West Indies to the Continental Army. In May 1776, as Congressmen rode home to ask their conventions for authority to vote for independence, Deane landed in France to negotiate arms shipments. By December he wrote Congress that he had shipped 200,000 pounds of gunpowder and 80,000 pounds of saltpeter from France to Martinique and 100,000 pounds of gunpowder from Amsterdam. By the end of 1776 congressional agents operated openly in all the Dutch, Spanish and French colonies in the West Indies and in European ports.

Historian Peter Andreas writes,

Merchants in France, the Dutch Republic, Spain, Sweden and the West Indies viewed the revolution as an opportunity for expanding their trade and profits. Though the governments of these countries and their dependencies avoided, they seldom interfered with entrepreneurs involved in contraband trade. Some merchants were permitted to remove “outmoded” arms from royal arsenals for a nominal sum even though their destination was obvious. Dutch arms manufacturers were operating their mills at full capacity by mid-1776.

Maryland’s agent in the free port of St. Eustastius, Abraham Van Bibber, reported that, while officially the Dutch had imposed an embargo on selling arms and munitions to Americans to mollify the British, “[t]he Dutch understand quite well that the enforcement of the laws, that is, the embargo, would mean the ruin of their trade.” “Statia,” as it became known, was the first foreign port to salute the American flag; no wonder, Dutch merchants on the island were selling gunpowder to the Americans at six times the going rate in Europe. Their rivals, the French, sent a deputation from a leading Nantes shipping firm to visit Washington at Cambridge; by November 1776 they were covertly supplying his army with thousands of dollars in war supplies.

By mid-1776 a river of arms, ammunition, cloth and quinine flowed through Louisiana into the Carolinas. Gunpowder smuggled in sugar hogsheads arrived in Charleston from Jamaica; from Bordeaux, three hundred casks of powder and 5,000 muskets sailed for Philadelphia—on ships flying French colors—to be hauled overland to Boston. Americans shipped tobacco to England through St. Eustatius; British manufactured goods found their way to New England via Nova Scotia. One Loyalist merchant complained to British vice admiral Molyneux Schuldham in January 1776 that “at most of the Ports east of Boston, [there were] daily arrivals from the West Indies, but most from St. Eustatius; every one brings more or less gunpowder.” By the summer of 1776 many of the several thousand American privateering ships—including six hundred carrying letters of marque from Congress—avidly transported contraband arms and goods and hunted for lucrative prize British merchantmen. Following the British evacuation of Boston, fully 365 privateers operated from this one port.

Privateering offered a high-risk path to overnight wealth. From nine highly profitable voyages, Joseph Peabody of Salem, Massachusetts, climbed from deckhand to investor to the port’s leading shipping magnate in six years, owning eighty ships and employing 8,000 men. Israel Thorndike, once a cooper’s assistant, became a privateer’s captain and one of New England’s wealthiest bankers. The Cabots of Beverley operated one of Massachusetts’ most profitable privateering firms. Washington’s quartermaster general, Nathanael Greene of Rhode Island, invested in privateering voyages. He asked one associate to keep his involvement secret and proposed using a fictitious name. When Congress tried to investigate Greene for allegedly diverting public money for his own business ventures, Washington blocked the inquiry to preserve military morale. James Forten, the free black grandson of a Maryland slave, served as powder boy—the most dangerous job—on a privateer; captured on his first voyage, he taught marbles to the son of a British admiral and survived to become America’s first black millionaire, owner of a sail-making loft, inventor of the sailing winch and the man who bankrolled the anti-slavery weekly newspaper, William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator.

So profitable was privateering that the Continental Navy and the eleven state navies had difficulty recruiting crewmen. Many sailors deserted Continental Navy ships, lured away by the prospect of a share of a privateer’s loot. One wealthy privateer investor, John Livingston, worried that peace would ruin him “if it takes place without proper warning.” As historian Peter Andreas opines, “The war at sea was at least as important as the war on land, yet for the colonies it was fought almost entirely by what was essentially a profit-driven mercenary force.”

The leading American commercial agent, Silas Deane, sent to Paris in July 1776 to surreptitiously procure arms, posed as a Bermuda merchant. He worked with merchant-playwright Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais through a dummy mercantile house, Rodrigue Hortalez et Cie, created to mask official French cooperation. Openly supplying contraband weapons to the rebellious American colonies would violate French neutrality under international law. By late 1777, eight arms-laden ships transported 2,000 tons of munitions to the Continental Army through Martinique for transshipment by American vessels. The French ships brought 8,750 pairs of shoes, 3,600 blankets, more than 4,000 dozen pairs of stockings, 164 brass cannon, 153 (gun) carriages, more than 41,000 balls, 37,000 fusils, 373,000 flints, 15,000 gun worms, 514,000 musket balls, nearly 20,000 pounds of lead, 161,000 pounds of powder, 21 mortars, more than 3,000 bombs, more than 11,000 grenades, 345 grapeshot, 18,000 spades, shovels and axes, over 4,000 tents and 51,000 pounds of sulphur.