Having finally reached Charleroi at 3pm, Vandamme’s troops had to file across the bridge and through the narrow, congested streets of the town. Other than the Guard, which Napoleon would be very loath to commit so early in the campaign, his was the first infantry formation to pass through Charleroi heading towards the east. Lefol’s division led the march and the young Lieutenant Lefol recalls,

After passing through Charleroi, we saw 150 to 200 disarmed Prussians that our soldiers looked at with interest. They were some of the prisoners made during the day by the 1st Hussars, commanded I think by General Clary, whose bravery had brought about this result.

Having despatched the 1st Hussars towards Brussels, the remainder of Pajol’s corps was directed along the main road towards Gilly and Sombreffe, towards which most of the Prussian defenders of Charleroi had retreated. Still awaiting the arrival of Vandamme, Napoleon also sent forward the division of the Young Guard, less the regiment sent up the Brussels road, to support him. General Ameil, with the 5th Hussars, acted as the advance guard, but had not gone far when he came under fire from the Prussian rearguard around Gilly. Biot, one of Pajol’s aides de camp wrote,

The 1st Hussars moved through the suburb of Gosselies; the rest of the cavalry followed the suburb of Gilly. This is bordered on each side, along its entire length, with an uninterrupted line of houses; it thus formed a very dangerous defile for cavalry.

We profited from the first suitable location to form closed column by regiment. Then General Ameil with the 5th Hussars was sent on reconnaissance to the exit of the suburb. There he was saluted by volleys of musketry and artillery fire; the enemy occupied a plateau under the fire of which the main road passed.

Pajol’s memoirs describe his actions and the Prussian position:

At first, Pajol pushed his scouts onto the different points of this position. The resistance that they encountered left him in no doubt that the enemy was determined to defend themselves there. Conforming to the emperor’s orders, Pajol stopped his troops and awaited some infantry. However, he did not cease to harass his enemies and skirmished along the whole line.

A little before 1pm, Grouchy appeared with Exelmans’ dragoons. He conducted his own reconnaissance of the enemy position and took command of the situation. He then had Pajol’s regiments massed on either side of the Namur road and took Exelmans’ cavalry to the right, in the direction of Châtelet. Not wanting to carry out an attack without infantry, he simply skirmished with the Prussian advance posts whilst awaiting the arrival of III Corps.

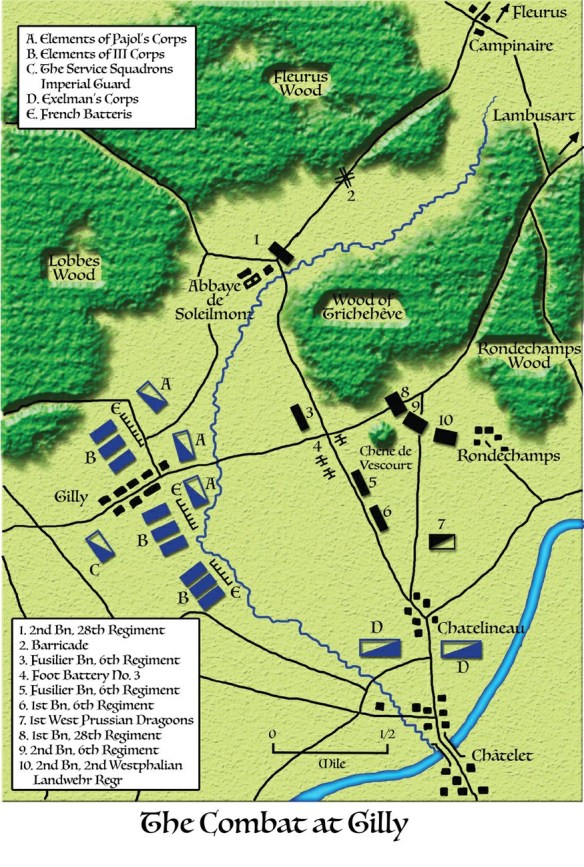

Pirch II profited from this time to complete his deployment and established his men a little to the rear of the junction of the roads to Fleurus via Campinaire and Namur, by Lambusart. His first line, composed of four battalions, stretched from the abbey of Soleilmont to close to Chatelineau, parallel to the road which ran between these two points; the battalion on the right held the Soleilmont abbey and was covered by abatis on the Fleurus road and as far as the Lobbes wood. The three other battalions deployed along the line and in front of the Trichehève wood, extending to the south of the Namur road. To their left, a regiment of dragoons observed the exits of Chatelineau and Châtelet. Finally their artillery was distributed along the Fleurus road and on the slopes, firing down onto the road exiting Gilly. In the second line, Pirch II had established three battalions astride the Namur road and at the entry to the Rondechamp wood; they occupied all the space between le chêne de Vescourt and the village of Rondechamp.

Colonel Count de Bloqueville, who was one of Grouchy’s aides de camp, later recounted the events in the run-up to the combat.

When the marshal had passed through Charleroi, he moved at the gallop along the road from Charleroi to Fleurus as far as the village of Gilly, where he saw a body of Prussians in position. Followed by a single aide de camp, he got as close as possible to the enemy who appeared to be about 20,000 strong. Then, protected by several clumps of trees which were spread along the edges of the small river which ran along a valley which separated the Prussians from Gilly, he explored the banks and returned to Gilly from where he sent his aide de camp Pont-Bellanger to the emperor to request permission to attack the Prussians and to request him to send some reinforcements, notably infantry, in order to carry out this attack.

Whilst waiting for a response from Napoleon, the marshal led General Exelmans’ dragoons round to the right as far as a mill where the horses would be able to cross the small river. From where they could cross, the marshal, profiting from the lay of the ground which did not allow the enemy to observe the movement of the dragoons, placed them so that they would be able, at the first signal, to outflank the Prussian left and charge their flank.

Whilst Grouchy conducted his reconnaissance, others were taking sensible precautions against a Prussian counter-attack. Chef d’escadron Biot tells us,

During our reconnaissance, a company of sapeurs was rushed to fortify the houses of the Gilly suburb that we were occupying. Infantry were deployed there as it arrived in order to resist the enemy in case they attempted to retake the suburb and throw us back on the bridge that our infantry and artillery continued to cross.

The emperor was obviously not impressed when he received Pont-Bellanger’s report; he no doubt felt that Grouchy should not have awaited orders, but immediately attacked Zieten and pushed on to Fleurus as he had been previously directed. He immediately set off for Gilly, annoyed at the holdup and determined to get the advance re-started. Before he left, he ordered Soult to write to Gérard to cross the river at Châtelet instead of Charleroi. This would have two advantages; firstly it would avoid congestion in Charleroi which was already holding up Vandamme’s march, and secondly, it would bring IV Corps onto the flank of the Prussian position; if he arrived early enough the Prussian rearguard might well be destroyed.

Letter from the major-général to Gérard 15 June, 3.30pm

- le comte Gérard, the emperor charges me to order you to move yourself and your corps to Châtelet where you are to cross the Sambre and advance following the road to Fleurus, the direction that the emperor is following at this moment with part of the army with the aim of attacking an enemy corps that has stopped in front of the wood of Lambusart. If this corps is still in position after you have crossed the Sambre, you are also to attack it. Let me know your positions and inform me if the 14th Cavalry division is with you; if so, you are to advance with it.

Napoleon arrived at Gilly at about 4.30pm and met up with Grouchy. His irritation is clear in his memoirs:

The corps of Vandamme and Grouchy were both at Gilly. Misled by false reports they wasted two hours without moving, in the belief that 200,000 Prussians were behind the woods and in front of Fleurus. I made a personal reconnaissance of the enemy and, judging that these woods were only occupied by two divisions of Zieten’s corps, consisting of between 18,000 and 20,000 men I forthwith gave the order to move forward.

In fact, all Vandamme’s troops were not yet fully up and Napoleon moved back to hasten their march. To the emperor’s frustration, the combat did not start until 6pm. Joining the troops as they prepared to launch their attack, Napoleon came across the 37th de ligne, one of whose officers reported,

… our divisions were massed on the plateau of Charleroi, where they waited for a time. Suddenly the emperor appeared on his horse in the middle of our columns. He addressed some words to the officer closest to him,

‘What regiment?’

‘Sire, the 37th’

‘Ah! Gauthier’s regiment? Your soldiers have poor greatcoats’

‘The Prussians have new ones’

‘They are there, go and take them!’

Pirch II’s brigade actually only consisted of a total of around 6,500 men in three regiments each of three battalions (the 6th and 28th Infantry Regiments and the 2nd Westphalian Landwehr), some cavalry from the corps cavalry reserve and an artillery battery. They had imposed on Grouchy and delayed his advance for several hours.

Some of Vandamme’s corps were committed as soon as they came forward. Lieutenant Lefol wrote, ‘Continuing our march, we encountered the enemy towards 6pm, and after taking part in a bloody combat where we lost many men … ‘ Pajol reported something similar: ‘The head of III Corps arrived in front of Pirch II’s positions towards 3pm. Vandamme attacked them immediately, but was unsuccessful.’

It appears that Vandamme, perhaps sensing the emperor’s frustration, launched Lefol’s division in a premature attack. Then, realising that a single division was insufficient for the task, was forced to wait until his whole corps came up. Pajol again:

He [Vandamme] was forced to wait for his whole corps to get forward and to combine his attacks with cavalry. Grouchy and Vandamme adopted the following deployment. Three infantry columns of infantry marched, one towards the Trichehève wood and the abbey of Soleilmont; another against the Prussian centre, following the Lambusart road; and the third against the Prussian left, turning Gilly. Exelmans’ dragoons went towards the Chatelineau mill to cross the stream at a ford and throw themselves, thanks to the cover of the ground which hid them from view, into the rear left of the Prussian position. Pajol’s cavalry marched to the left of Vandamme’s columns along the Fleurus road.

Informed of these deployments and of the attack which was about to be launched against Pirch II, Napoleon left Ney, to whom he had just given his orders and command of the left wing, and moved in all haste to Gilly. He arrived there towards 4.30pm. The attack was initiated by a violent artillery barrage aimed at the Prussian batteries. The infantry columns were then ordered forward.

This time, faced by a co-ordinated all-arms attack by superior forces, and with his flank threatened by Gérard, Pirch II chose this moment to order the retreat before they became decisively engaged. Thus it seems, Vandamme’s corps advanced but did not come into contact with the Prussians. General Berthezène reported: ‘The III Corps, having found the enemy had withdrawn, continued its march towards Fleurus and took position on the road a little in the rear of this small town.’ We cannot be sure who provided the three columns that Pajol speaks of; some accounts mention that one of them was made up of a regiment of the Young Guard and the others from Vandamme’s corps. Clearly, the whole of III Corps were not involved.

Napoleon, seeing that the Prussian infantry were escaping, hastened Vandamme’s advance, but he must have realised that infantry would not catch the retreating Prussians. He therefore turned to his aide-de-camp and former commander of the Guard Dragoons, General Letort, and ordered him to take the four service squadrons and to wipe out the Prussian battalions as they moved towards the entry to the woods behind them. At the same moment, Pajol launched his cavalry on Soleilmont to seize the defile into the wood of Fleurus and Exelmans’ dragoons swept onto the Prussian left from their covered position, scattering a small Prussian infantry force and forcing back the cavalry that was covering this flank. In his report on the action, Exelmans wrote to Grouchy:

I have the honour to inform Your Excellency that in the affair that took place yesterday under your eyes, General Vincent’s brigade had two officers and twenty dragoons wounded and seven killed. The brigade did its duty perfectly. Led by the brave General Vincent who combines a rare and great experience, firmness and sang-froid, I pray Your Excellency to ask the emperor for him to be made a higher grade in the legion d’honneur.

Colonel Briqueville (of the 20th) behaved very well, also the commander of the 1st Squadron; as this officer is very senior, I ask for the rank of major for him. [He then goes on to list the men he wants promoted/decorated, including ‘Grenadier Pissé (of the 20th Dragoons) who made twenty-seven prisoners.’]

The Prussian battalion positioned close to the Trichehève wood threw themselves into the trees. The two battalions to its left formed into square and marched towards the woods, stopping now and then to stand against Letort’s charges, supported by the Prussian cavalry. Letort moved forward to demand the square’s surrender; the battalions were from Berg, an old German state ally of the French, and perhaps he thought they may be prepared to change sides. However, the response was a shot that knocked him from his saddle. He died later in Charleroi.

One square became disordered, was broken, sabred and mostly destroyed (this was the fusilier battalion of the 28th), but the other managed to reach the safety of the Rondechamp wood, from which the three reserve battalions had already set off towards Lambusart. The right-hand battalion of the first line finally found protection behind the abatis that protected the Fleurus road and escaped into the wood, where it broke down into skirmishers and heavily engaged Pajol’s cavalry which was marching on the direct road from Gilly to Fleurus. Despite having imposed considerable delay on the French, Pirch II’s regiments suffered badly during this action. The fusiliers of the 28th lost 13 officers and 614 men; the fusilier battalion of the 6th lost a total of 216 killed wounded and missing.

The firing in the woods continued for a long time. The battered battalions of Pirch II’s brigade succeeded in reaching Lambusart where they were covered by Jagow’s 3rd Brigade, which had been in position there since 4pm. Despite the difficulties of the tracks and the enemy skirmish fire, Pajol’s regiments, after having taken a great number of prisoners, exited from the Fleurus woods sometime around 6.30pm, at about the same time as Exelmans’ dragoons left the Trichehève wood. At the sight of these two cavalry corps, Jagow and Pirch II retired from Lambusart to Fleurus. Satisfied with the results of the action at this point, Napoleon left with the Imperial Guard cavalry and returned to Charleroi where he could update himself on Ney’s situation and where he intended to pass the night.

In line with the emperor’s intentions and instructions, Grouchy left the corps of Pajol and Exelmans to continue the pursuit of the Prussians in the direction of Fleurus. Pajol, who was then marching with Subervie’s division on the direct route to Fleurus, passed close to the farm of Martinroux and launched Domon’s division to his left towards Wangenies along the Bonnaire road, whilst he advanced Soult’s division on his right towards Lambusart.

Biot described the difficulty of the ground for cavalry:

The road that we took to Lambusart is an elevated track, very narrow and bordered by woods on both sides. The enemy had made abatis out of trees across the road to slow our march as much as possible, for we were very close. His artillery sent us several balls from time to time, but to which we did not reply. An aide de camp to General Soult had his arm ripped off.

The scouts of these three divisions harassed the enemy rearguards but without being able to make any great impression on them. It required infantry to really interfere with the Prussian retreat. Pajol resolved to await Vandamme, who only reached the exits of the woods towards 7.30pm.

Grouchy had ordered Vandamme to continue to advance on Fleurus to support Pajol’s and Exelmans’ corps, but Vandamme, whose soldiers had been marching and fighting hard for more than twelve hours, refused, saying his men were exhausted. Grouchy was furious, but Vandamme had not been informed that he had been put under his command and that he should obey the marshal’s orders as commander of the right wing. He ordered his troops to bivouac. Lieutenant Lefol records: ‘Our division went into bivouac in a small wood between Charleroi and Fleurus, which had been previously occupied by the Prussians.’