‘Am concerned at check developing at Keren. Abyssinia might be left, but had hopes Eritrea would be cleaned up’ – read the telegram to Cairo of a worried Winston Churchill on 20 February 1941. The mountainous escarpment of Keren formed a natural fortress barrier shielding the coastal province of Eritrea from the interior of Africa. Italy had annexed Eritrea in 1890 and from there Mussolini’s armies had overrun Ethiopia (Abyssinia) in 1935-6. Now, five years later, they had made Keren the bastion of II Duce’s East African Empire against British invasion from the Sudan. Keren was to be a soldier’s battle in the grimmest imaginable conditions and terrain and here as nowhere else in the Second World War Italian soldiers of all types were to belie the belief that they were a pushover in battle.

As early as August 1939, General Sir Archibald Wavell, British Commander-in-Chief in the Middle East, concluded that there were four things he must do in the event of Italy going to war alongside Germany. These were to secure the Suez Canal base by acting boldly in the Western Desert; get control of the Eastern Mediterranean; clear the Red Sea; then develop operations in south-east Europe. After Mussolini’s entry into the Second World War in June 1940 Wavell wrestled to achieve these objectives. What he had not foreseen was that he would be required to do all four simultaneously with inadequate resources. Yet in spite of some nasty shocks he managed the first of these tasks and was wholly, startlingly, successful in the third. It is of this campaign, the clearing of East Africa and the Red Sea, that Keren formed a part.

Wavell’s strategic dilemma is admirably depicted and the one bright spot on an otherwise dark canvas is suitably illuminated by his cable to Winston Churchill in the last week of March 1941, after Keren had been captured. It was in reply to a message from the Prime Minister expressing alarm at Rommel’s advance to El Agheila, and it helps to set the battle in its proper context:

I have to admit taking considerable risks in Cyrenaica after capture of Benghazi in order to provide maximum support for Greece . . . Result is I am weak in Cyrenaica at present and no reinforcements of armoured troops, which are chief requirement, are at present available . . . Have just come back from Keren. Capture was very fine achievement by Indian divisions. Platt will push on towards Asmara as quickly as he can and I have authorised Cunningham to continue towards Addis Ababa from Harrar, which surrendered yesterday.

Wavell had four campaigns on his hands — Cyrenaica, Greece, Eritrea and Ethiopia. It was essential to get the East African battles over and done with. Ethiopia had to be dealt with quickly in order to send the much-needed troops back to the Western Desert where the dangers were so much greater – point which Rommel was shortly to rub home. But before this could be done, before troops and stores could be sent via the Red Sea port of Massawa to Egypt and so on to Libya and Greece, the Asmara-Addis Ababa road had to be captured. And in the way stood the fortress of Keren.

On 19 January 1941, Lieutenant-General William Platt advanced from the Sudan into Eritrea, while a few days later Lieutenant- General Sir Alan Cunningham set out on his march from Kenya with African and South African troops. Platt quickly reached Keren but the battle for it, the most severe of the whole East African campaign, lasted nearly two months. After its capture Platt soon took Asmara and Massawa, thus opening the vital route to the north. Cunningham’s successes were equally astonishing in speed and distance. By 25 February he had taken Mogadishu together with a huge petrol dump, and a month later, having advanced 1,000 miles, reached Harrar. By 5 April he had captured Addis Ababa and then the two forces, Platt from the north, Cunningham from the south, converged on Amba Alagi.

It was here that the Duke of Aosta, Italian Viceroy of Ethiopia, had concentrated what was left of his armies. By 16 May all was over. The extent and totality of the victory were summed up by Wavell in his despatch: The conquest of Italian East Africa had been accomplished in four months … in this period a force of 220,000 men had been practically destroyed with the whole of its equipment, and an area of nearly a million square miles had been occupied. It was that rare thing – a complete victory, a battle of annihilation since none of the enemy escaped. The fighting was unlike any other in the war. Great mountain barriers had been stormed. In Ethiopia the operations, among which Orde Wingate’s Gideon force ranks high, had been largely guerrilla, and had succeeded in tying down large numbers of Italian troops which were thus unable to concentrate against the advancing British columns. Yet these columns had been small and this was their strength, since supply problems, although formidable, had been surmountable. Mobility had been everything, while for the Italians the very size of the huge Empire they tried to protect had paralyzed them. How did the situation appear to the Italian Viceroy?

Despite the Italians’ early and relatively insignificant successes of July 1940 when they captured frontier posts in Kenya and Sudan and invaded British Somaliland, Aosta’s strategy was essentially defensive. By the beginning of December 1940 he was already expecting British offensives from the Sudan against Eritrea, particularly from Kassala towards Keren, and from Kenya against Italian Somaliland and Ethiopia. Because of fuel and vehicle shortages it was difficult to ensure that his centrally held reserves would be sufficiently agile to reinforce a threatened area rapidly. He therefore decided to send some of these reserves forward, especially in the north towards Eritrea where he rightly thought that the first blow would fall.

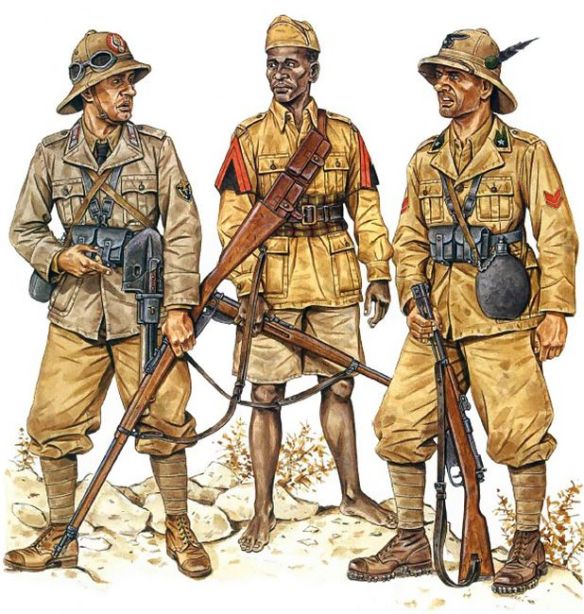

In Eritrea itself he ordered the local commanders to organize areas of resistance which were to be firmly held while mobile reserves, mainly colonial brigades, would be prepared to operate between these areas and attack an advancing enemy’s flanks. Eritrea contained three colonial divisions and three colonial brigades plus garrison troops. These native troops, Askaris , would be peculiarly susceptible to reverses and their loyalty would be unlikely to survive serious setbacks. In the north, where Generale di Corpo d’Armante Luigi Frusci commanded, the Viceroy foresaw grave difficulties in countering the British mechanized forces which would advance across flat country near the Sudan-Eritrea frontier, and on 11 January 1941 he therefore sought Mussolini’s agreement to the evacuation of Kassala, Tessenei and Gallabat-Metemma. II Duce agreed. On the other hand, Aosta decreed that there would be no withdrawal from Agordat and Barentu, both south-west of Keren, and that Keren itself would be strengthened by a regiment of the elite Savoia Grenadier Division. In this way they would help `to close the gap absolutely.’ Such was the situation shortly before Platt began his advance. He had two very famous Indian Divisions under his command – the 4th (which Wavell had sent from Libya in January thereby taking the sort of risk he pointed out in his telegram to Churchill) and the 5th stationed in the Sudan since September 1940. These divisions were made up largely of Indian troops, ideally suited to the mountain warfare which they were about to wage, but there were British battalions and other units too. Platt had also formed the 1,000-strong Gazelle Force partly from units in 5th Indian Division, notably the renowned Indian cavalry regiment, Skinner’s Horse, and from the Sudan Defence Force. The group included machine-gun, artillery and supporting units and was commanded by the dashing Colonel Frank W. Messervy. While Platt was still on the defensive, Gazelle Force had been used to harass and ambush Italian troops in and near Kassala. So successful were they that the Italians withdrew from Kassala by mid-January.

General Platt’s task was clear. He must advance from Kassala into Eritrea and take Massawa, a distance as the crow flies of about 230 miles. There were only two ways of getting there and both routes led through Agordat to Keren. The northern route, a poor and narrow dry-weather road, was via Sabderat and Keru; the southern one was a better road but less direct and went through Tessenei and Barentu to Agordat. A well-surfaced road ran from Agordat to Keren and then on to Asmara and Massawa. The whole country was in one sense ideal for war. Except for the few towns, roads, railways and bridges, there was, as in the desert, little made by man to be destroyed. Yet curiously enough the place was alive with game. For the soldiers themselves it was less hospitable – mountainous, arid and rough. `The plains and valleys’, wrote Lieutenant-General Sir Geoffrey Evans, `were a mixture of jungle or open spaces dotted with outcrops of rock, stunted trees, palms near water and scrub, the mountains, strewn with boulders of immense size, spear grass and thorn bushes, were extremely arduous to climb in the heat, particularly when the troops were loaded with a full pack, ammunition and often an extra supply of water since there was none on the slopes.’

Fifth Indian Division was to advance to Agordat by Tessenei and Barentu, while 4th Indian Division with two of its brigades made for the same objective via Keru. The third brigade of 4th Indian Division was to move to Keren from Port Sudan. The whole advance began with Gazelle Force in the lead on the northern route. There was a certain amount of excitement before they reached Agordat. On 21 January, as a divisional history has recorded,

while Messervy was engrossed with the situation at Keru, a nearby patch of scrub erupted. With shrill yells a squadron of Eritrean horsemen, 60 in number raced on the gun positions in front of Gazelle Force Headquarters. Kicking their shaggy ponies to a furious gallop, the cavalrymen rose in their stirrups to hurl small percussion grenades ahead of them. With great gallantry they surged on, but the gunners brought their pieces into action in time to blow back the horsemen from the muzzles of the guns.

There could have been few such bizarre actions during six years of war. The intrepid horsemen, led in by an Italian officer on a white horse, left 25 dead and 16 wounded on the field of battle.

More serious business confronted Gazelle Force. The battle for the heights to the south of Keru Gorge required the combined efforts of 4th Battalion, 11th Sikh Regiment, Skinner’s Horse and 2nd Cameron Highlanders against firm Italian resistance. Even then it was more the danger of being outflanked and cut off from the south by 10th Brigade of 5th Indian Division than direct frontal pressure which caused the Italians to abandon their positions. By 25 January 4th Indian Division had closed up on Agordat, had cut the Barentu road and faced their first real obstacle. Meanwhile 5th Indian Division was ordered to take Barentu. Italian resistance there was stubborn, and just as 10th Brigade’s advance had helped 4th Indian Division to capture the Keru Gorge heights, so 4th Indian Division’s subsequent success at Agordat allowed the 5th to overrun the Italians at Barentu on 2 February.

The battle for Agordat resolved itself into a struggle for Mount Cochen, described by those who saw it as `a steep and involved ridge system which sprang to a height of 1,500 ft, its rugged barrier extending into the east until it ended above a defile four miles long through which the road to Keren passed. The Agordat and Mount Cochen position was held by the Italian 4th Colonial Division, which was then attacked by two brigades, the 5th and 11th, of 4th Indian Division. The gallant actions of Indian and British infantry were greatly assisted by four T (Infantry) tanks whose job it was to knock out the Italian armor. Lightweight Bren-gun carriers were used to lure the Italian tanks out of their hides. The bait was taken with a vengeance. Eighteen Italian tanks burst from cover and raced to destroy the flimsy intruders. Then the T” tanks barged into the open, their guns playing on their Italian adversaries at point-blank range. Six medium and five light tanks went up in flames. The survivors scuttled frantically into cover.

On the crests of Mount Cochen itself the final action had been dramatic and bloody. The Italian commander then had dispatched a company of Eritrean infantry to contain Indian troops advancing on the peak itself so that he could withdraw his main body to new positions. But the Eritreans encountered a covering force of some 40 Rajputana Rifles and Pathan Sappers and Miners who Tell on the Eritreans like furies, plying the steel and leaving a wake of dead and wounded behind them. The survivors scattered in frantic flight. Over 100 bodies were counted along the slopes after. No further resistance was met as 11th Brigade advanced along the heights and made good the eastern end of the Cochen ridge system overlooking the Keren road.’ It seemed at this moment as if the road to Keren itself was open. The cost had not been high. Fewer than 150 casualties had been suffered by Major-General Sir Noel M. Beresford-Peirse’s two brigades while the Italian 4th Colonial Division had disintegrated, losing over a thousand prisoners.