The first night radar Kill

During the summer of 1952, VMF(N)-513 received the F-3D “Skynight,” the squadron’s first jet aircraft. With the new jet fighter, VMF(N)-513 made aviation history with the first radar kill on an enemy jet aircraft at night and was credited with 10 confirmed night kills during the Korean Conflict.

As the situation became desperate in the Pusan perimeter, Gen. Douglas MacArthur requested marines to help in the defense. The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade was formed of marines from every base in the United States and from the reserves. The brigade’s air arm consisted of two squadrons: VMF(N)-542, flying F7F-3Ns from its base at Cherry Point, North Carolina; and VMF(N)-513, flying F4U-5Ns out of El Toro, California. VMF-323 and VMF(N)-513 were loaded aboard the USS Sitkoh Bay and sailed on August 24, 1950. VMF-212 and VMF(N)-542 embarked on the USS Cape Esperance on August 27. The brigade’s air arm arrived in Japan on July 31. VMF-214 and VMF-323 checked out at Itami Air Base and then flew to the escort carriers, USS Sicily and USS Badoeng Strait. The night-fighter squadrons flew from Itazuke Air Base (AB) on the west coast of Japan. VMF(N)-513 flew day and night strikes in support of the marine brigade, and it also flew for Army units. VMF(N)-542 had security and strip alert at Itazuke AB.

From September 3 to 14, VMF(N)-513 flew seventy-nine day and night close air support (CAS) missions in support in the Pusan perimeter. As the defense stabilized around Pusan, MacArthur was planning the invasion of Inchon. The 1st Provisional Marine Brigade was pulled out of Pusan and embarked to join the 1st Marine Division for the landing at Inchon on September 15. As the marines advanced, they captured the airfield at Kimpo and, on September 19, VMF(N)-542 moved with their F7F-3Ns from Itazuke AB to Kimpo, near Seoul, and began operations. The squadron had only twenty trained night-fighter pilots. The rest were reservists with good experience and a desire to become night fighters. The squadron claimed the distinction of flying the first marine combat mission from Kimpo at 0735 on September 20 when four F7F-3N air- craft destroyed two enemy locomotives after expending 3,000 rounds of 20-mm ammunition. The 5th Marines exercised extreme care to minimize damage to the location because they knew that planes flying from that field would help them in the near future.

During this time, VMF(N)-513, flying their F4U-5Ns out of Itazuke, sup- ported General Walker’s breakout from the Pusan perimeter. Between September 17 and 19, the squadron flew fifteen daylight CAS missions for U. S. Army units. As the planes ranged over the entire extent of the Pusan perimeter, they attacked enemy troops, tanks, vehicles, and artillery. Meanwhile, VMF(N)-542 was flying support missions for the 1st Marine Division as it attacked northward. When Wonson AB was captured, VMF(N)-513 flew from Itazuke. Night operations did not begin until late October, when runway lights became available. They flew daytime missions with VMF-312 under the control of tactical air control parties (TACPs). Both night-fighter squadrons continued to sup- port the marines as they advanced northward. As all air units continued to harass supply lines, the North Koreans began to move more supplies at night, the time when the night fighters were most effective. During the Chosin Reservoir campaign, VMF(N)-513 and VMF-542 flew day and night in support of the marines. On December 31, the two night-fighter squadrons flew twenty CAS missions. On December 7, 1950, 1st Lt. Truman Clark of VMF(N)-513, flying a torpedo bomber, the TBM Avenger, helped evacuate 103 casualties from Koto-ri. Capt. Malcolm G. Moncrief, Jr., of VMF-312, a qualified landing signal officer, directed the torpedo bombers into Koto-ri with paddles. After the evacuation at Hungnam, the two night-fighter squadrons were flying into Itazuke, patrolling the skies between Japan and Korea.

In January 1951, VMF(N)-542 assumed the duties of VMF(N)-513, which deployed to K-9 at Pusan. Beginning on January 27, the squadron flew armed reconnaissance missions and an occasional deep support mission for the Eighth Army. As the allies pushed northward, VMF(N)-542 received orders to conduct long flights from Itazuke to as far as Seoul, Korea, and to maintain continuous patrols to report enemy attempts to cross the frozen Han River. They shot up camp areas, convoys, and other lucrative targets. In addition to all of the various duties they were assigned, they also served as spotters to direct naval gunfire. Late January saw the first successful instance of marine air-to-ground cooperation since the Chosin Reservoir campaign. In February, VMF(N)-513 moved from Itami, Japan, to K-3 Pohang on the east coast of Korea. VMF(N)-542 transferred from Itami and Itazuke to K-1 Pusan. In March, VMF(N)-542 was sent home to El Toro, California, for conversion and training in the F3D Sky Knight all-weather jet fighters. The squadron’s F7F-3Ns were left with VMF(N)-513, now a composite squadron, attacking from K-1 during the day with its F4U-5Ns and during the night with its F7F-3Ns. During May, the planes of VMF(N)-513 killed hundreds of Chinese soldiers.

In late May, marine R4D transports were outfitted to drop flares. They worked together with the F7Fs and F4Us to illuminate targets at night. On June 12, the Navy provided the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing with PB4Y-2 Privateers for the night-illumination missions. The planes would fly in the general area, and when one would find a likely target, they would join up. The flare plane would drop flares and the night fighters would fly beneath them and attack targets of opportunity. This was extremely hazardous because the enemy would know they were being targeted. The operation was almost always conducted along known supply routes in deep valleys among the mountains, and the enemy was known to stretch cables between the mountains over the routes. These missions were eventually terminated due to the high cost of men and planes. Afterward, the planes patrolled on their own, searching for targets. Mostly, they were looking for truck convoys driving with their lights on. The attrition rates dropped because the enemy was no longer forewarned by the flares.

In June, VMF(N)-513 moved to K-18 at Kangnung on the east coast of Korea. The 4,400-foot-long runway was reinforced with pierced steel planking. This field was only forty miles behind the 1st Marine Division, a proximity that allowed the aircraft much more time over the target. During this period, the enemy was flying light planes over the main line of resistance (MLR), even over the Seoul area. One such plane was the Po-2, a biplane made mostly of wood and fabric which made it difficult to pick up or track by radar. The Po-2s would drop mortar shells and other types of ordnance that proved more of a hindrance and bother than anything else; they acquired the nickname, Bedcheck Charlie. The Po-2 could fly at 60 mph, whereas the lowest speed that an F7F, with wheels and flaps down, could safely maintain was 110 mph, a speed that did not allow it to make any turns. The F4Us were not much better. In June, July, and September, two F7F-3Ns and one F4U-5N each shot down a Po-2 by using radar intercept. In June 1952, an F4U-5N shot down a Yak-9. As hard as it was to intercept and shoot down these Bedcheck Charlies, the effort to do so at least had the effect of chasing them away.

Another mission of VMF(N)-513 was nightly patrols to protect Cho-do, an island ten miles off of the west coast of North Korea and north of the Haeju peninsula. Cho-do had a radar installation and an air-sea rescue service, and the dusk-to-dawn mission was to protect it from being bombed at night. Loitering on station for the night was a monotonous, though necessary, duty, but planes returning over the Haeju peninsula were free to attack any targets of opportunity that presented themselves.

Another tasking that allowed closer air support on the MLR at night was the MPQ radar missions flown by the F7F-3Ns. At the beginning, a pilot would fly the plane while maintaining a prescribed altitude and speed. He would arm the plane according to instructions from a radar plotter on the ground. The plotter would give directional requests and tell the pilot when to release ordnance, which could be one bomb at a time or all ordnance at once. Bombs carried on these missions ranged from 250 to 2,000 pounds. After dropping any ordnance, the pilot would always watch for secondary explosions. The planes were even- tually adapted so that the pilot had only to maintain altitude and speed. The ground operator would still request the ordnance he wanted dropped on each run, and the pilot would fly the plane to the target and attack. This became very accu- rate and effective. The pilots were called in by forward observers, and damage reports would sometimes be given before the planes left the area.

The F7F-3Ns also escorted Air Force B-26 Invaders on nightly interdiction missions. These missions were hard on the B-26 radar operator because some missions lasted for as long as six hours and the radar operator was jammed into a small space originally designed to hold an eighty-gallon gas tank. Largely unable to move during a mission, the operator was exposed to freezing temperatures that were difficult to endure.

On March 30, 1952, VMF(N)-513 moved from K-18 to K-8, from Kangnung in the east to Kunsan on the west coast, 105 miles south of Seoul. Of note is that this move was accomplished without losing even one day of operations. K-8 was an Air Force base, and the squadron was reinforced because it was the only marine squadron on the base. At that time, VMF(N)-513 was flying both the F7F-3N and F4U-5N. Now the night interdiction missions were becoming extremely hazardous because the MLR was stagnant. The enemy was able to concentrate very heavy antiaircraft artillery along their main lines of supply. Planes sat on strip alert nightly and would scramble whenever enemy planes were spotted south of the MLR.

Another mission for the F7Fs added at this time was night close air support (NCAS) on the MLR for the 1st Marine Division. The plane would be loaded with eight new types of firebombs which did not explode in one big fireball like napalm, but would travel above the ground and spread fire in all directions. The bombing run would commence at 5,000 feet, and the pilot would release the bombs on the pull-up at 1,000 feet. Accuracy was improved by two searchlights that crossed their beams on a mountaintop several miles back. The F7F would arrive on station and report to a spotter plane, which would use crossed search- light beams as a reference to provide directions for the first drop. After the first drop, the spotter would give the direction from there to drop the other bombs. After eight of these drops, it would seem as if the whole mountain were on fire. The effectiveness of these firebombing mission was enhanced with a slight-but unofficial-change in tactics. The pilot of the first plane would delay his takeoff for a short period, and the next pilot would hurry up and leave a little early, so that they arrived at the target area at approximately the same time. As the first plane began its bombing run, the second plane would start strafing behind it. When the first plane finished its runs, the second would bomb while the first strafed behind it. This was neither sanctioned nor known officially, but it proved very effective. Pilots received very little ground fire because the enemy troops knew they would get personal attention. Just imagine three planes in the same area at night without running lights. These were very successful missions and broke the back of many enemy attacks.

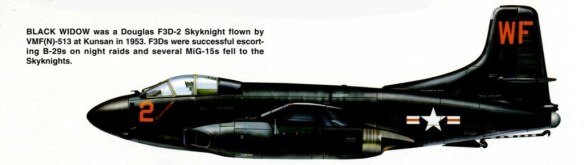

During the late summer of 1952, VMF(N)-513 received twelve F3D Sky Knight night fighters. With this acquisition, the 513th became the only squadron with three types of planes actively flying combat missions at the same time during the Korean War. After some modifications, F3Ds began assisting on the night combat air patrol (NCAP) missions for Cho-do. About this time, the F4Us were phased out and the F3Ds were training to escort the nightly B-29 raids. These raids would require as many as eight F3Ds at one time. Due to the limited time an F3D could be airborne compared to the time the B-29 would be in flight, escort for the bombing run from the MLR to the target and back required several planes. One plane would pick up the B-29s at the MLR and escort them to the initial point. Another plane would then escort them to the target. One plane would perform combat air patrol over the target area, and the other F3Ds would escort the B-29s out across the MLR. This system proved so effective that B-29s losses ceased. At times, two targets being struck simultaneously would increase the workload on the escort planes and crew.

As the F7Fs were being phased out during the first few days of May 1952, the crews transitioned to the new F3Ds. The radar officers (ROs) learned the new radar and navigation equipment while still flying F7F missions. The pilots were also switching to the F3Ds.

By June, VMF(N)-513 had moved to K-6 Pyontaek, about fifty miles south of Seoul. Its mission was now mainly escorting the B-29s and performing NCAPs over Cho-do. The F3D had a fantastic radar at that time. It had long- range mapping, and its range reception was very good. It had a target lock-on system that virtually ensured a hit if the target was within range, and it was able to shoot down enemy planes without its pilot ever seeing them. Until the ceasefire, F3Ds continued escorting B-29s and patrolling over Cho-do. After the cease-fire, the F3Ds patrolled south of the 38th parallel until they redeployed to Japan.

The F4U was well known as a CAS plane from World War II. In the postwar period, it was equipped with radar and made into a night fighter, but with a single pilot, it was difficult to fly because he had to operate the radar simultaneously. The F7F began flying at the end of World War II and did not see any combat in that conflict, but it too was later configured as a night fighter and patrolled in China after World War II. With the addition of a radio observer (RO) doing the navigation, part of the radio work, and directing the pilot on intercepts, it was an easier life for the pilot. The F7F may have been the toughest fighter plane ever built. It often came home on one engine, many times dragging wires or parts of trees, and with cables wrapped around it. The F3D was a new plane with state- of-the-art equipment. With a crew of two and the bulky radar equipment, it was not as fast as other jets of the era, but its interception equipment and tail-warning radar made it one of the best planes.

There was a significant difference between the pilot’s and RO’s jobs in the two planes. The F7F was noisy and cold, whereas the F3D was quiet and warm. In the F7F, the RO sat with his feet four inches below his rear, and he could not stretch out. The cockpit was so narrow that he was unable to put both arms down beside his body. The canopy was so close to the seat that, if he was taller than five feet eight inches, he had to ride with his head bent forward. The plane was equipped with South Wind gasoline heaters that never seemed to work. Riding in this cramped, cold position for as long as six hours and unable to move was difficult and uncomfortable. Also, sitting between the two engines made it hard to hear anything. The ROs flew in any clothing they could find to try to keep warm on missions. However, after a crewman was lost due to exposure, we got rubber exposure suits. We were issued “Mickey Mouse” thermal boots which helped, but because a man could not move his feet for the entire flight, his feet still got extremely cold. Bailing out of the F7F was a problem for the RO. The pilot would go out between the cockpit and the engine in front of the wing. However, the RO, sitting lower than the top of the wing, had to roll out onto the wing after he released his canopy. If he went out too high, he would be blown onto the elevator. If he went out too low, the airflow would hold him on the wing. He had to rise up just enough to be blown off low.

Transitioning from the F7F to the F3D was like riding a motorcycle in the winter and then getting into a limousine. In the F3D, you sat side by side in a cockpit that was pressurized and heated or cooled, as the situation demanded. You entered the plane through a forty-inch square hatch on top of the cockpit. To bail out, the crew had to use a tunnel between the seats that exited from the bottom of the plane. The main thing to remember was to not go out head first. For its time, it was a wonderful plane and a pleasure to fly. Marine night fighters were introduced during the island battles of World War II and later improved into what was used in Korea. That was the end of combat flying for night fighters because all planes since then were used as both day and night fighters, and the squadrons were designated as attack squadrons.

None of the aforementioned accomplishments would have been possible without the dedication and sacrifice of all of the support people in the squadron. The planes were maintained in excellent condition, and the entire squadron was well taken care of, in spite of some primitive conditions. Missions were never missed or curtailed due to lack of maintenance. When the squadron moved to new bases, flying operations were never missed. Pilots took off from the old base, flew their missions, and simply landed at the new base. This put an unbelievable strain on support personnel, but they never failed to complete their mission.