Fighting against the Red Army had taught German veterans of the eastern front almost every trick imaginable. If there were shell holes on the approach to one of their positions, they would place anti-personnel mines at the bottom. An attacker’s instinct would be to throw himself into it to take cover when under machine-gun or mortar fire. If the Germans abandoned a position, they not only prepared booby traps in their dugouts but left behind a box of grenades in which several had been tampered with to reduce the time delay to zero. They were also expert at concealing in a ditch beside a track an S-Mine, known to the Americans as a ‘Bouncing Betty’ or the ‘castrator’ mine, because it sprang up when released to explode shrapnel at crotch height. And wires were strung taut at neck height across roads used by Jeeps to behead their unwary occupants as they drove along. The Americans rapidly welded an inverted L-shaped rod to the front of their open vehicles to catch and cut these wires.

Another German trick when the Americans launched a night attack was for one machine gun to fire high with tracer over their attackers’ heads. This encouraged them to remain upright, while the others fired low with ball ammunition. In all attacks, both British and American troops failed to follow their own artillery barrage closely enough. Newly arrived troops tended to hang back on the assumption that the enemy would be annihilated by the bombing or the shellfire, when in fact he was likely to be temporarily concussed or disorientated. The Germans recovered rapidly, so the moment needed to be seized.

Tanks supporting an attack were used to put down a heavy curtain of machine-gun fire at all likely machine-gun positions, especially in the far corners of each field. But they also caused a number of casualties to their own infantry, especially with the bow machine gun firing from a lower level. Infantry platoons often used to yell for tank support, but sometimes when their armour appeared uninvited, they were indignant. The presence of tanks almost always attracted German artillery or mortar fire.

The Sherman was a noisy beast. Germans claimed that they always knew from the sound of tank engines when an American attack was coming. Both American and British tank crews had many dangers to fear. The 88 mm anti-aircraft gun used in a ground role was terrifyingly accurate, even from a mile away. The Germans camouflaged them on a hill to the rear so that they could fire down over the hedgerows below. In the close country of the bocage, German tank-hunting groups with the shoulder-launched Panzerfaust would hide and wait for a column of American tanks to pass, then fire at them from behind at their vulnerable rear. Generalleutnant Richard Schimpf of the 3rd Paratroop Division on the Saint-Lô front noted how his men began rapidly to gain confidence and lose their panzerschreck, or fear of tanks, after disabling Shermans at close quarters. Others would creep up on tanks and throw a sticky bomb, like the Gammon grenade which the American paratroopers had used to such effect. Some would even climb on to the tank, if they could approach unseen, and try to drop a grenade into a hatch. Not surprisingly, companies of Shermans in the bocage did not like to move without a flank guard of infantry.

Germans often sited an assault gun or a tank at the end of a long straight lane to ambush any Shermans which tried to use it. This forced tanks out into the small fields. Unable to see much through the periscopes, the tank commander had to stick his head out of the turret hatch to have a look, and thus presented a target for a rifleman or a stay-behind machine gun.

The other danger was a German panzer concealed in a sunken track between hedgerows. Survival depended on very quick reactions. German tank turrets traversed slowly, so there was always the chance of getting at least one round off first. If they did not have an armour-piercing round ready in the breech, a hit with a white phosphorus shell could either blind the enemy tank or even panic its crew into abandoning their vehicle.

In the fields surrounded by hedgerows, tanks were at their most vulnerable when they entered or left a field by an obvious opening. Various methods were tried to avoid this. The accompanying infantry tried Bangalore torpedoes to make breaches in a hedgerow, but this was seldom effective because of the solidity of the mound and the time needed to dig the charge in. Engineers used explosive, but a huge quantity was required.

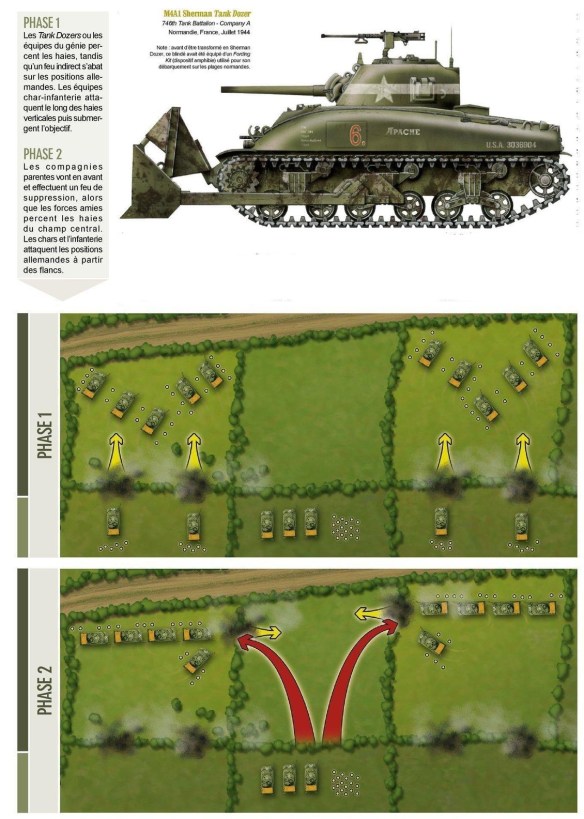

The perfect solution was finally discovered by Sergeant Curtis G. Culin of the 102nd Cavalry Reconnaissance with the 2nd Armored Division. Another soldier came up with the suggestion that steel prongs should be fitted to the front of the tank, then it could dig up the hedgerow. Most of those present laughed, but Culin went away and developed the idea by welding a pair of short steel girders to the front of a Sherman. General Bradley saw a demonstration. He immediately gave orders that the steel from German beach obstacles should be cut up for use. The ‘rhino’ tank was born. With a good driver, it took less than two and a half minutes to clear a hole through the bank and hedgerow.

One of the most important but least favourite pastimes in the bocage was patrolling at night. A sergeant usually led the patrol, whose task was either to try to capture a prisoner for interrogation, or simply to establish a presence out in front in case of surprise attacks. German paratroopers on the Saint-Lô front used to sneak up at night to lob grenades. Many stories were elaborated around night patrols. ‘I talked to enough men,’ wrote the combat historian Forrest Pogue, ‘to believe the tale of a German and an American patrol which spent several days under a gentleman’s agreement visiting a wine cellar in no-man’s land at discreet intervals.’ He also heard from one patrol leader that his group had ‘reported itself cut off by the enemy for three days while they enjoyed the favors of two buxom French girls in a farmhouse’. But even if true, these were exceptions. Very few men, especially those from the city, liked leaving the reassuring company of their platoon. American units also used patrolling to give newly arrived ‘replacements’ a taste of the front line. But for a sergeant in command of some terrified recruits ready to shoot at anything in the dark, a night patrol was the worst task of all.

The most important reason why the Americans failed to plan sufficiently for fighting in the bocage was because in Montgomery’s original campaign plan, much of the bocage was to be bypassed. The Allies were to pivot southeastward by taking Caen on D-Day. There the Falaise plain offered many more and better roads and wide-open fields for armor deployment. Of course, Montgomery did not take Caen on D-Day or soon thereafter.

Despite the obstacles of the bocage, the US Ninetieth and Ninth Infantry Divisions and the Eighty-Second Airborne Division hacked and chewed their way through these hedgerows and the entrenched Germans with more Yankee grit than any tactical finesse. The most apparent weakness in the American June ground attack was the lack of sufficient training given to the infantry divisions to coordinate with separate tank battalions. Armor and infantry radios operated on different channels. To develop mutual infantry-armor confidence and awareness, the tanks in Normandy installed infantry-type radios tuned to the infantry radio net. Army signal companies also attached telephones or microphones so that infantrymen were connected with the tankers inside

The tanks are no better off. They have two choices. They can go down the roads, which in this case were just mud lanes, often too narrow for a tank, often sunk four to six feet below the adjacent banks, and generally deep in mud. The Class 4 roads were decent in spots, but only for one-way traffic, with few exits to the adjacent fields. An armored outfit, whether it is a platoon or an armored army, attacking along a single road attacks on a front one tank wide. The rest of the tanks are just roadblocks trailing along behind. When the first tank runs into a mine or an 88 or 75 shell, it always stops, and it usually burns up. And it efficiently blocks the road so the majestic column of roaring tanks comes to an ignominious stop.

The next step is to try to find out where the enemy gun or tank is, and wheel up a tank or so to shoot at him. The only trouble is, only the men in the first tank saw the German’s gun flash, and they aren’t talking any more. The tanks trying to get into position to do some shooting are easily seen and get shot before they can do much about it. I have seen it happen. In the hedgerows it is almost impossible to get firing positions in the front row, and in the rear you can’t see the enemy anyway so no one bothers. Usually the tanks waited for the infantry to do something about it.

Instead of charging valiantly down the road, the tanks may try to bull their way through the hedgerows. This is very slow and gives the enemy time to get his tanks or guns where they can do the most good. Then he just waits. And in the solution, there is always a minor and local problem to be solved, a problem which caused a certain amount of irritation, and that is, who is going over the hedgerow first, the infantry or the tank? It is surprising how self-effacing most men can be in such situations.

Anyone who actually fought in the hedgerows realizes that, at best, the going was necessarily slow. A skillful, defending force could cause great delay and heavy losses to an attacking force many times stronger. This, because the attacker can’t use his fire power effectively and because he can’t advance rapidly except on the road where he is quickly stopped at some convenient spot.

There were a number of other factors which contributed to the difficulties of fighting through the hedgerows. The area was merely a succession of small enclosed pastures with a few orchards, likewise enclosed by hedgerows. Seldom could one see clearly beyond the confine of the field. It was difficult to keep physical contact with adjacent squads, platoons, or larger units. It was difficult to determine exactly where one was. Unlike conditions in open country, flanks could not be protected by fields of fire. All these contributed to the difficulties of control and caused a feeling of isolation on the part of small units. All this meant that the front-line troops thought their neighbors were nowhere around. They could not see them, they were not in the adjacent field, therefore they were behind. Often this feeling of being out on a limb would cause the leading elements to halt and wait for the flank units to come up (and sometimes these were ahead).

German counterattacks in the hedgerows failed largely for the same reasons our own advance was slowed. Any attack quickly loses its momentum, and then because of our artillery and fighter bombers the Germans would suffer disastrous loss. In fact we found that generally the best way to beat the Germans was to get them to counterattack a provided we had prepared to meet them.

Although the hedgerows were the most distinctive feature of the bocage region, the numerous rivers and marshes further aided the defense and impeded maneuver. The July 1944 fighting took place in the area dominated by the Vire and Taute rivers as well as associated rivers and streams. The numerous small rivers running through the coastal lowlands created several large marshes that further compartmentalized the terrain and made maneuver even more difficult. East of La Haye-du-Puits was the Marais-de-Ste.-Anne swamp, fed by the Séves River. Immediately south of Carentan was the Prairies Marécageuses de Gorges, a substantial marshland fed by the Taute River and many small tributaries. In the months prior to D-Day, the Wehrmacht flooded a number of areas by using dams or other obstructions in order to complicate any Allied attempts at airborne landings. The extent of these marshlands increased in late June 1944 since the early summer of 1944 was the rainiest on record since 1900.

US infantry units received no specialized training for combat in the hedgerows prior to the Normandy campaign. This was partly due to the concentration on the elaborate preparations for the amphibious landings on D-Day. In addition, there were misconceptions about the Normandy hedgerows. There were extensive hedgerows on the opposite side of the Channel in the southern English countryside. However, the English hedgerows were not as substantial as their Norman counterparts.

Most infantry weapons were not well suited to hedgerow fighting. German defenses were dug into the earthen base of the hedgerows, making them far less vulnerable to rifle fire. Furthermore, the extensive vegetation on top of the earthen base provided excellent camouflage and helped conceal the precise location of the German defenses. Light machine guns provided a somewhat better solution, since their volume of fire provided better suppression than aimed rifle fire.

As the GIs became more experienced in hedgerow fighting, other types of weapons were preferred. One of the most common weapons used in the bocage fighting was the rifle grenade. These could be fired from the normal M1 Garand rifle using an adapter that was fitted to the barrel and launched using a special blank cartridge. The rifle grenade could be fired from the normal shoulder position. However, to get maximum range, the rifle was fired from a kneeling position with the butt firmly against the ground and the rifle elevated to a 45-degree angle, giving it an effective range of about 55 to 300 yards depending on whether an auxiliary booster cartridge was used. The range of the grenade could be adjusted by using five range rings on the grenade adapter that altered the speed of the grenade depending on how deep the grenade stabilizer tube was mounted on the adapter.

The M1A1 2.36in. “bazooka” rifle launcher was another popular weapon in the bocage fighting. These weapons were not widely distributed in the rifle companies, with only five per company. Once their value in bocage fighting became evident, many infantry divisions took the bazookas allotted to service units and headquarters units and transferred them to the rifle companies. Although intended primarily for anti-tank defense, their high explosive warhead was effective against dug-in defenses. From late June to late July 1944, US infantry fired nearly 53,000 bazooka rockets, mostly against targets other than tanks.

The US Army avoided using field artillery close to friendly troops. This was not only due to inherent problems of accuracy. The use of field artillery in the bocage was complicated by the possibilities of projectiles prematurely detonating over friendly troops if they came into contact with trees and overhead branches when fired on a shallow trajectory. As a result, the 60mm M2 light mortar became the workhorse of the infantry for close-range fire-support. This could fire a mortar bomb from 100 to 1,985 yards, enabling the weapon to cover the gap between the forward edge of battle and the inner limit of field artillery support. Each rifle company had three 60mm mortars.

As in all armies, the combat performance of American troops in every battalion varied greatly. During the bocage battles, some GIs began to get over their terror of German panzers. Private Hicks of the 22nd Infantry with the 4th Division managed to destroy three Panthers over three days with his bazooka. Although he was killed two days later, confidence in the bazooka as an anti-tank weapon continued to increase. Colonel Teague of the 22nd Infantry heard an account from one of his bazooka men: ‘Colonel, that was a great big son-of-a-bitch. It looked like a whole road full of tank. It kept coming on and it looked like it was going to destroy the whole world. I took three shots and the son-of-a-bitch didn’t stop.’ He paused, and Teague asked him what he did next. ‘I ran round behind and took one shot. He stopped.’ Some junior officers became so excited by the idea of panzer hunts that they had to be ordered to stop.

In five days of marsh and bocage fighting, however, the 22nd Infantry suffered 729 casualties, including a battalion commander and five rifle company commanders. ‘Company G had only five non-coms left who had been with the company more than two weeks. Four of these, according to the First Sergeant, were battle exhaustion cases and would not have been tolerated as non-coms if there had been anyone else available. Due to the lack of effective non-coms, the company commander and the First Sergeant had to go around and boot every individual man out of his hole when under fire, only to have him hide again as soon as they had passed.’

4th Division

For the second night running German troops had infiltrated 8th Regiment’s lines, forcing Battalion commanders to rely on their artillery to keep the enemy at bay. Poor communications and harassment of the supply lines delayed 70th Tank Battalion, leaving 1st Battalion to advance unsupported. It had only advanced a short distance when it stumbled on a strongpoint; Lieutenant-Colonel Simmons would have to wait until the Shermans arrived. 1st Battalion’s progress through the maze of hedgerows was slow (it took six hours to advance 1,000 metres), and an after-action report sums up the difficulties faced by the GIs as they fought their way through the ‘bocage’ around Cherbourg:

‘In effect, hedgerows subdivide the terrain into small rectangular compartments which favour the defence and necessitate their reduction individually by the attacker. Each compartment thus constitutes a problem in itself. On approaching such a compartment, the scouts must be particularly watchful, especially on the corners, where the enemy is frequently found commanding approaches from adjacent compartments. Fire from automatic weapons, light mortars and rifle grenades, directed at corners and along the hedgerows themselves, whether or not an enemy was known to be present therein, was found to be frequently effective.

‘The entire operation resolved itself into a species of jungle or Indian fighting, in which the individual soldier or small groups of soldiers played a dominant part. Success comes to the offensive force, which employs the maximum initiative by individuals and small groups.’

The intensity of the fighting in the bocage proved alarming. The US 4th Infantry Division suffered 5,452 casualties in less than three weeks of fighting, a hint of the horror to come in July 1944 in the “Green Hell” of the bocage country around St Lô.